The Camden Town Group into the London Group: Some Intimate Glimpses of the Transition 1911–14

Malcolm Easton

Drawing on interviews with, and letters from, members of the Camden Town Group and their wider circle, Malcolm Easton describes the group’s transition into the larger London Group in 1913. First published in 1967, Easton’s text was an early piece of scholarship in this field, signalling a revival of interest in the group and the period.

This study, made possible by the generous co-operation of Elizabeth Manson, is based on a collection of letters, minutes, and other documents which once belonged to James Bolivar Manson. An able and sensitive young painter, Manson joined the staff of the Tate Gallery in 1912, meanwhile acting as secretary to the Camden Town Group and later to the London Group. In addition, I have made use of letters belonging to Orovida C. Pissarro, and letters presented by her to the Ashmolean Museum; I am grateful to both owners.

*

The twentieth-century story of Fitzroy Street, in the Borough of St Pancras, really begins, as Hubert Wellington tells us, when ‘the word went round, “Walter has come back to London!”’1 That was in 1905. But ‘W. Sickert’ does not appear at No.19 in the Rate-books till 1907, and then with the qualification ‘S.O.’ after it: perhaps this signifies ‘studio only’, since Kelly’s Directory for 1907 lists Sickert at No.8, formerly leased to Whistler and always one of the younger artist’s favourite haunts. We need not go into the question of how many other rooms and studios Sickert lived and worked in, which, in the hands of a modern J.T. Smith, would provide an amusing enough topic for a rainy day. Here it will be sufficient to note that the Directory links Sickert at No.19 with a surgical bootmaker called Ackrell: this is from 1908 to 1911. By 1912, Ackrell’s name alone survives, and Sickert’s thereafter never reappears. Manson later stated, categorically: ‘The Studio at 19 Fitzroy Street where the Camden Town Group met was not Sickert’s; it was rented by the Group and used only for the purpose of showing their pictures.’2 The one survivor of the Camden Town Group has not been able to recall how, precisely, the contributions were pooled or to whom they were paid.3

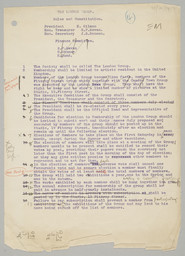

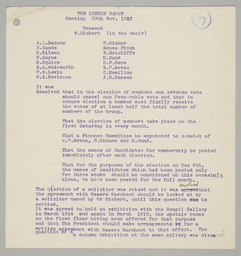

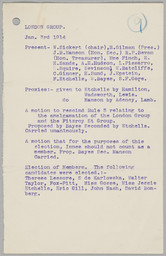

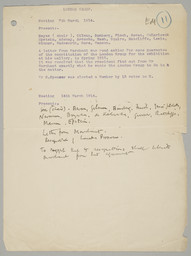

I have gone into this matter in some detail, since it was the ‘Studio’, or first-floor back and front, at 19 Fitzroy Street which formed the headquarters of the artists referred to here, and where all meetings – certainly up to the last attended by Manson, on 7 March 1914 – took place. The rooms can be seen today. Roughly paced, the front and larger of the two measures fifteen by twenty feet. It is now bleak storage-space; but, to remind us of its former glory, canvases loading the racks and easels dragged forward for display, there is a print of Malcolm Drummond’s little plate, 19 Fitzroy Street,4 for which the University possesses a preliminary study. Up the stone stairs worn like chopping-blocks, on 2 December 1911, trooped most of the Camden Town Group for a meeting which was primarily to decide whether the sixteen-strong membership should be increased. Sickert (as always, up to and including a London Group night of 3 January 1914) took the Chair; Gore fulfilled the duties of president; Manson made jottings for his minutes. But the debate had to be brought to a halt. What was the use of electing more members when, for the moment, the Carfax Galleries could not provide room enough for the present sixteen to show more than four works each? Gilman had cut in early with a motion which, it was suddenly realised, made further talk superfluous. However, a majority of those present (Lamb, Ginner, Lewis, Bevan, Gore, Drummond, Ratcliffe, among the more emphatic) had by then declared their wish that numbers be increased. Manson afterwards considered this a meeting decisive in the history of the transition, since the idea of a larger society, foreshadowing the London Group of nearly two years later, was raised for the first time on that occasion.5

*

Siding with the few (Sickert, Lucien Pissarro, Manson) that is, speaking in favour of a small society in any circumstances, was that very elusive person, John Doman Turner. Vox et praeterea nihil: he seems never to have opened his mouth in this company again.

Frank Rutter gives some bare facts about Turner: ‘an amateur in watercolour – afflicted with deafness – whom I had introduced to Gore, who subsequently taught him painting by correspondence, in a series of wonderful letters which should still exist somewhere’.6 The letters did – and do – exist; and though the excerpts I shall give here must necessarily be brief, it will at least be the first time that the correspondence has been discussed in print. Somerset House has very little to add to Rutter’s brief description. A retired stockbroker’s clerk, Turner died in 1938 at the age of sixty-five. The will, set out in his own meticulous, copperplate hand, offers no additional information beyond the names of his wife and a neighbour who witnessed the signature. Among Manson’s papers there are three early letters contemporary with the events considered in this article, and a last one, dated 1936, which directly concerns itself with the instruction he had received from Gore. He says that, while the originals had been returned to the artist’s widow, he has just rediscovered his personal copy of the correspondence. ‘In addition to the letters’, he goes on, ‘I have always kept a number of early sketches in a portfolio by themselves, as Gore had scribbled, faintly in pencil, all sorts of advice and curses with regard to their technique. What shall we do about this, please?’ It would seem that Manson (then Director of the Tate Gallery), wisely no doubt, did not encourage Turner in his wish that these annotated drawings of his should be exhibited; and they have since disappeared. Manson did, however, take charge of Turner’s copy of the letters.

Soon after this curious document came into my hands, it was possible – through the kindness of Frederick Gore, A.R.A. – to see typescript copies of the originals still in the possession of his mother. Spencer Gore had addressed some thirty-two letters to Turner, not all of which have survived intact or were concerned with instruction. Several are mere notes dashed off in a moment, especially in 1913, the last year of the correspondence (Gore himself died, tragically young, in 1914). The arrangement between the two men is made clear in an initial letter, dated 8 June 1908: Gore undertakes to criticise any work Turner likes to send him, at five shillings a time. The drawings were numbered for easy reference and posted as often or seldom as the pupil wished. Turner sent off the packets from his home in Streatham, and they were returned with Gore’s comments from, variously, Hertingfordbury, Clayhidon (when, as frequently happened, he was staying with H.B. Harrison), and from two London addresses, Granby Street and Mornington Crescent. For Turner himself, it would remain an experience – associated with one of the most lovable and talented of artists – to be pondered over and treasured for the rest of his life.

*

The manuscript totals ninety sheets in the recipient’s hand. Though every recipe and axiom is diligently preserved, he felt obliged to make certain cuts. These help to provide a much-needed portrait of Turner: over-fearful of giving offence, too ready to take it, rather philistine. All the same, it is Gore in whom we are primarily interested, as we read these letters, unstudied, often positively indolent in their phrasing. They are full of wisdom. Above all, they underline the need to draw, draw, draw ... ‘draw anything that interests you’:7 for Rutter is wrong – Gore did not take very seriously the responsibility of teaching Turner to paint. Earlier on, the Sickertian tips come thick and fast. For example: ‘It is much better to start in the middle of a bit of paper and let your drawing grow out to each side as far as it wants to ... A drawing should grow like a plant grows, gradually, round one point’;8 and: ‘A figure exists as part of its surroundings. The length of a leg is the space it takes up, measured by the things behind it.’9 Nor is Gore anxious to conceal the origin of his precepts. ‘Nearly everything I have told you,’ he writes, at one point, ‘comes through Walter Sickert from Degas.’10 His admiration for Menzel, on the other hand, seems very personal, especially when he praises him in the same breath as Michelangelo.11

What the teacher had to wrestle hardest with, was his pupil’s longing to reach some sort of technical perfection overnight. It brought out all Gore’s own splendid contempt for quick returns. He could not understand the agonies of doubt suffered in this respect by a man five years his senior: ‘If you wait until you can draw perfectly, you will have to wait till you are dead, because there is always something fresh to learn. Degas doesn’t consider that he can draw yet, and you must know Hokusai’s famous saying at the age of 80.’12 Turner felt nervous, working under the public gaze at South Kensington (his study: the Museum’s casts) or in the theatre. He would have to get used to it, Gore told him. Drawing from memory led only to mannerism: ‘A drawing is an explanation of an observation.’13 Yet the observer must remain detached. It so happened that both Gore and Turner were making studies of popular acts at the Bedford (Turner showed a ‘Duncan and Godfrey’ – ‘jolly duo from the great days of the Halls’ – at the first Camden Town Group exhibition in June 1911).14 Gore, pondering a sketch by his pupil, says: ‘I have always had too great an admiration for Victoria Monks to be able to make a decent drawing of her. One is liable to be too particular. You must forget that she interests you at all while you draw her. Victoria Monks, like everybody else, is only a part of her surroundings.’15 It would be dangerous to draw too sharp a distinction between Gore’s aristocratic enjoyment of low life and the Bloomsbury embodiment of ‘Cambridge ideals of unworldliness’.16 Grant, for instance, had a foot in both camps. And I recall a photograph (belonging to Mrs Bagenal) which shows some of Bloomsbury’s brightest stars in a circus sideshow, perched comically over the wings of a painted aeroplane. Yet we should surely not have found in Fry so solid, and thus so artistically inhibiting, a regard for Miss Monks making her nightly supplication: ‘Won’t you come home, Bill Bailey?’ It can be conceded, all the same, that Gore often forgot his shyness where other goddesses were concerned, and that he rightfully belonged in the company of those other two connoisseurs of the music hall whose maxims he was never tired of quoting.

Though, finally, he offers some advice on painting as well, the letters are overwhelmingly concerned with drawing; and I conclude these brief excerpts on a characteristic note that still echoes Sickert and Degas: ‘The whole secret of drawing, and learning to draw, is to draw for a purpose. Never for the sake of drawing. If you draw only for the sake of drawing you will remain a perpetual art student.’17 But timidity triumphed. By late 1913, Turner was protesting his unworthiness to accept membership of the London Group, to which as a Camden Town original he had been automatically elected; and not even Gore’s urgent requests persuaded him to stay long enough to exhibit at the ambiguous Camden Town-London Group show which opened in Brighton on 16 December 1913.

*

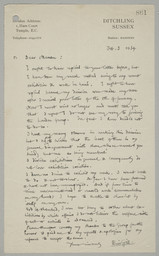

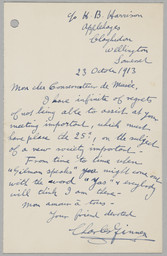

On 23 October of that year (to go back a month or two), Ginner, who could be waggish as well as witty, sent the following apology to Manson, now just approaching the end of his first twelve months as Assistant to Aitken at the Tate:

Mon cher Conservateur de Musée,

I have infinite of regrets of not being able to assist at your meeting important, which must have place the 25th, on the subject of a new society important.

From time to time when ‘Gilman speaks’ you might come out with the word ‘Yas’ and everybody will think I am there.

Mon amour à tous –

Your friend devoted,

Charles Ginner.

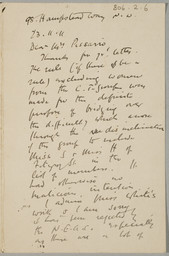

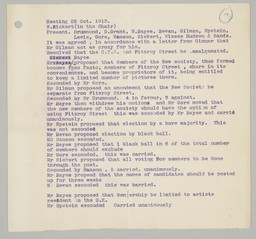

The few lines make a joke of his Frenchified speech, as noticed by Hubert Wellington (I have said that Ginner was brought up in France); play upon his attachment to the views of Gilman – even though these may be expressed with the pomposity Sickert has satirised in ‘Gilman speaks’;18 and humorously admit to the drawling ‘Ya-as’, which all who knew him never forget. They also furnish the earliest reference we have to what would later be called the ‘London Group’. Manson always regarded the London Group as dating from the occasion to which Ginner alludes, that ‘meeting important’ which was to take place on 25 October 1913.19 His minutes show that the process of expansion had already begun, Gilman’s objections having been satisfied. For William Marchant, who ran the commodious Goupil Gallery in Waterloo Place, had taken over from Arthur Clifton of the cramped Carfax. Epstein now appears, as representative of sculpture; and, more surprisingly, two ladies, Miss Ethel Sands and Miss Anna Hope Hudson. Two years before, much embarrassed by Esther Pissarro’s persistent demands that her friend Diana White be elected to the Camden Town Group, Manson had given the only explanation I know of for the exclusion of women from the earlier society: it was, he said, ‘for the definite purpose of bridging over the difficulty which arose through the disinclination of the Group to include Miss S. and Miss H. of Fitzroy Street in the list of members’.20 We may presume that, once the ban was lifted, Sickert’s longstanding friendship with the two women secured them priority.

Election procedure, with a much wider casting of the net, was the chief item on the agenda. It was finally decided that a candidate must obtain the votes of at least half the members, and a list went out. Just back from Ireland, Lamb wrote to Manson on the 28th: ‘What a pity Stanley Spencer is not suggested: he has a younger brother, too [Gilbert], whose first picture is of infinite promise. I suppose I must attend meetings before grumbling.’21 He did attend the next, that of 15 November 1913.

*

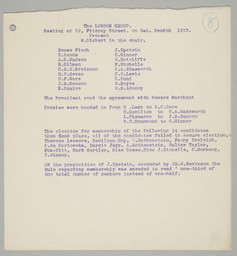

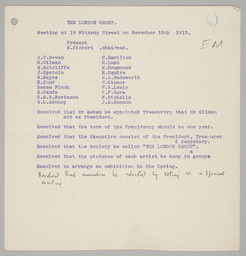

By then, membership had been extended to Renée Finch and her husband Harald Sund (of Scandinavian origin), to Cuthbert Hamilton, E.A. Wadsworth, Harold Squire and W.B. Adeney.22 It was at this meeting, Sickert being in the Chair, that Gilman succeeded Gore as President, Manson retaining the Secretaryship, and the ‘New Society’ became in name the ‘London Group’. Post-impressionism had split the art world in two. As Clive Bell recalled later, ‘to many of us post-impressionist meant anti-impressionist’,23 and Lucien Pissarro found the election of men like Hamilton and Wadsworth intolerable, since they, callower (as it seemed to him) than Lewis, expressed a creed even further removed from the old ideals of the Camden Town Group. ‘Fancy people joining with the idea of forming a teetotaller society,’ he wrote, ‘and coming to the conclusion that in order not to be narrow-minded they must admit some drunkards!’24 Gilman, not long afterwards, sought to close the breach by explaining that there must still be artists who could not be classed as either ‘realists’ (under which heading he now appeared himself) or ‘formulists’: their job would be to link the two.25 But Pissarro, to Gore’s sorrow,26 declined to be won over, and continued to shun all meetings under the new constitution.

Nor was the division always between realists and formulists.

As you know [Pissarro complained to Manson, on 22 December 1913] Sickert tries to dilute the little art elements of Fitzroy Street in a sea of amateurs and pupils of his – with probably the intention of destroying the art value of Fitzroy Street as he has destroyed the art value of the Camden Town Group.

Trust Gilman to see through that. He (Gilman) has arranged an unofficial meeting to discuss the situation. Can you come? We shall meet at the “Sceptre”, an eating-house of [a Gallicism, but correct] Warwick Street, Regent Street, at 7.30 tomorrow, Tuesday. Shall be present Ginner, Bevan, and myself.27

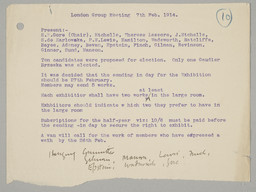

And whatever flag one sailed under, whether one was a disciple of Lewis or a faithful flatterer of Sickert, the odds against success in an election just then were overwhelming. At the meeting of 6 December, out of fourteen candidates (including sweethearts and wives; old friends like Walter Taylor; distinguished performers outside the charmed circle such as the Rothensteins, Gertler, and Bomberg), all failed. Something had to be done. On 29 November, it was decided to alter the number of votes required by candidates from one-half to one-third, and on another ballot of 3 January 1914, Thérèse Lessore, Mrs Bevan, Jessie Etchells, Bomberg, Taylor, Sylvia Gosse, Fox Pitt, John Nash and Eric Gill passed the less stringent test; Paul Nash, Gertler, and the Rothensteins being among the seventeen who failed.28 After that, successes prove meagre again: on 7 February, out of ten candidates, Gaudier-Brzeska only; on 7 March, out of six, Stanley Spencer only – to quote from the later occasions on which Manson was there to note down the result.

The Secretary received letters from both successful and unsuccessful candidates. Verpilleux wrote anxiously to know how he had failed to win support.29 Eric Gill, on the contrary, declined the honour paid him. He explains himself thus, in a letter of 3 February 1914:

I have many reasons in making this decision but I beg you to believe that the least of them is my general disagreement with those whose names you kindly sent me as being members. I dislike exhibitions in general and consequently do not love exhibition societies.

I have no desire to exhibit my work. I want work to do and not to show. So far I have been favoured and have not been unemployed. And if from time to time uncommissioned or unsold work accumulates on my hands I hope to buckle to and show it by itself on my own.

God be thanked, I am too busy to bother about exhibitions, by which affairs I do not believe the welfare either of art or artists is advanced.

Please therefore convey my thanks to the Group for the honour it paid me and my regrets and apologies for my refusal to accept the same.30

The first exhibition under the title ‘London’ was discussed at the meeting of 7 February. It took place on 5 March, under Marchant’s aegis, at the Goupil Gallery. As far as press and public were concerned, vorticism swamped the show. To use Pissarro’s terms, the ‘drunkards’ triumphed over the ‘teetotallers’.31 A week later, on 14 March 1914, there took place the last meeting attended by Manson, and so the last with which I am concerned here. The minutes are cursory in the extreme, indicating the secretary’s almost total loss of interest. Significantly, on this final occasion, before his own withdrawal, he had to report the resignation of his dearest friend, Lucien Pissarro. Harold Squire’s absence on 14 March has also its significance: for, three months later, Pissarro, Manson and Squire – joined by Malcolm Milne and Diana White32 – held a secessionist show of their own at the Carfax. Sickert’s attitude had for some time been much more than avuncularly disapproving: a two-months absentee from the meetings at 19 Fitzroy Street, he soon felt obliged to end his public silence and conduct a wrathful (though amusing) campaign in the newspapers against post-impressionists and futurists alike.33

*

Ginner tells us that it was Epstein who actually hit upon the name ‘London Group’ (Studio, November 1945). Epstein, too, as the minutes of the meeting of 29 November 1913 record, had led the move to make election easier. With the achievement – and the scandal – of the Wilde monument just behind him, he was again enjoying (somewhat wryly) the kind of notoriety that had followed upon the unveiling of the Strand statues. When the New Society required a ‘progressive’ to represent British sculpture, who could have disputed the ballot with Epstein? He was, moreover, particularly fond of Manson, who in 1903 had been for a while his fellow student at Julian’s. Since then, they and their families had continued to meet34 and the two men often found ways of being of use to each other.

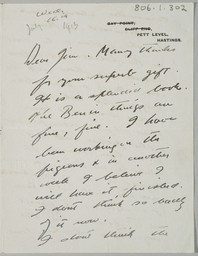

Epstein, as it happens, was little in London during the summer of 1913, but lived in jealously guarded seclusion at Pett, near Rye. By a fortunate chance, Lucien Pissarro had taken Western House, on the outskirts of the old town, so that when Manson slipped down for an occasional weekend’s painting and, later, spent his leave there, there were visits on both sides.35 They were therefore in closer touch than usual. ‘I have been working on the pigeons’, Epstein wrote to Manson, on 16 July: one of several such subjects in marble (‘doves’ they become, in Richard Buckle’s biography), from which he was to turn shortly to a series of carvings in flenite. This letter of his, however, is more concerned with the fate of a painting by one of the New Society’s earliest recruits, Mme Renée Finch. A ‘Nude’ of hers had been taken down from the walls of the current Allied Artists’ Association exhibition, accusations of ‘immorality’ having been made against it by the businessmen of the committee. Hilton Carter, manager of the Albert Hall, was ‘persuaded to order its removal under threat of police intervention’.36 That Epstein felt himself involved may be taken as a reminder of the close relationship that existed between members of what was shortly to be the London Group and those who contributed to the lively shows instituted by Rutter: they were, in fact, one and the same body of artists. Epstein himself appeared at AAA artists’ committees and hanging committees; just as, much earlier, some of the original Camden Town Group members had first become known to one another while engaged on Association duties. Rutter, in Since I was Twenty-Five, describes the ‘indecent’ painting episode in detail, but without mentioning the artist.37 Epstein’s letter supplies what is missing:

I don’t think the Committee should have compromised over Mme Finch’s picture, and to call in the police is ridiculous ...

It seems to me that we have created a sort of Frankenstein monster that will turn and destroy us, if things are to be done in the way shown at this last exhibition. The objection at bottom is really against the work ‘as a work of art’. Those rascals thought the picture ugly as well as indecent, and if they have their way the show won’t be different in time from the R.A. or the New English.38

No doubt this asperity had been accentuated by the writer’s own experiences, particularly in connection with his most recent public work: ‘I have just heard’, he tells Manson, with some bitterness, ‘that Ross [of whom Epstein was deeply suspicious] has had a fig-leaf or drapery manufactured for the Oscar Wilde tomb and the monument has now probably been made decent’;39 to which it is fitting, if melancholy, to add the rest of the story: that the Prefect of the Seine gave orders for the whole monument to be covered with straw.

Such philistinism was all the harder to bear, when the most innocent and appealing of Epstein’s works often failed to attract a buyer. A cast of the charming little ‘babe’s head’ – with the crumpled ear – remained unsold for a long while before passing into Manson’s own collection. It was again a fellow artist, Muirhead Bone, who came to the rescue by purchasing from the sculptor a copy of the portrait of Euphemia Lamb. ‘And just in time, for I am getting down to low ebb in my pocket’, was Epstein’s expression of relief at this.40

One day, in the same summer of 1913, Manson is informed by his correspondent: ‘I am coming in tomorrow to London, and will look in at the Tate. If this isn’t convenient for you, a line at the Poetry Bookshop, 35 Devonshire Street, Theobald’s Road, will find me.’41 The paternal figures of 19 Fitzroy Street would never shine like phares for Epstein, as once they had for Manson. Epstein, whose style at this moment owed much to Brancusi, was not on the look-out for recipes ‘through Walter Sickert from Degas’ or any longer ready to absorb the wisdom of Camille Pissarro while sitting at the feet of Lucien. He was happy to accept election to the New Society, find a name for it, and amend its constitution where necessary, but his energy was boundless – sufficient to take him all over the art-jungle (his word for it) without too much regard for any particular enclave. In the process, he got hurt – but he got work: work, ultimately, on a scale never dreamed of by the others. So at this moment he was busy investigating Harold Monro’s domain. In a letter of 14 November 1912, Gaudier-Brzeska gives us a picture of it:

All the poets have joined together to hire a big house near the British Museum, where they live and work and have underneath it a shop where they sell poetry by the pound – and talk to the intellectuals. Some of them have huge rooms, whilst those like Gibson have only a tiny hole. He is boxed in a room, over the door of which is written, ‘in case of fire, access to the roof through this room’.42

We don’t know what sort of a ‘tiny hole’ or ‘huge room’ – if any – might have been let to the Epsteins; or whether, when Gaudier rang their bell on one occasion, this happened to be in Devonshire Street, Great James Street, or Guildford Street. It is likely to have been the attic storey at one of these addresses, for Mrs Epstein, so we are told, had to lean far out to see who the visitor was, before Epstein would undertake the long descent and ascent to let him in.

*

One certainly learns from these documents that a number of errors exist in semi-official – and even official – accounts.43

And discovery of these errors encourages one to pursue the investigation further. All too soon, there will be no more witnesses – and the brick and stucco world of Sickert and his friends will have vanished long before that. Anybody who sets out to trace the painting-grounds of these artists, active only a short while ago, will be alarmed to discover how little remains above the surface. From 255 Hampstead Road to the south side of Robert Street, NW1 (with, transversely, most of the Euston area familiar to Sickert, who liked to dine at the station, and the whole former market bordering upon Albany Street, so dear to Robert Bevan) all is, or is about to be, obliterated. It is hardly less sad to see the wrecks left standing; the leprous condition of Mornington Crescent; or, far away in Pimlico, the down-at-heel character of Cambridge Street, Charlwood Street, and the precincts of St Barnabas: the world of Beardsley and Father Gurney is fast slipping back into the slum from which the Puseyites first rescued it; and slums foreshadow another levelling and the erection of more shoeboxes. The newer Hampstead of Manson and MacColl and the older Hampstead of William Rothenstein are not greatly changed, but this does not mean that their future is guaranteed.

It is indeed a happy accident that 19 Fitzroy Street – once the tenth, now the first, old house on the west side – should survive: plaqueless and forgotten, of course, but still structurally sound.

Bibliographical note

Published sources for this ‘transition period’ are naturally meagre. Those actually used appear in the Notes to the Appendix. However, I have not mentioned Quentin Bell’s ‘Unlikely Alliance’, an article dealing with the disparate elements fused for a moment into the London Group, which appeared in the Sunday Times Colour Supplement on 12 July 1964.

Published sources for this ‘transition period’ are naturally meagre. Those actually used appear in the Notes to the Appendix. However, I have not mentioned Quentin Bell’s ‘Unlikely Alliance’, an article dealing with the disparate elements fused for a moment into the London Group, which appeared in the Sunday Times Colour Supplement on 12 July 1964.

It is pleasant also to have an opportunity to pay tribute here to a masterly general account of British painting during the earlier twentieth century: Douglas Cooper’s Introduction (pp.19–59) to The Courtauld Collection, 1954. I found it helpful on this occasion, as on many others.

Notes

Duncan Grant tells me that he never visited 19 Fitzroy Street during the period when the Camden Town Group met to show and sell there.

He provided a note to this effect, when sending his collection of Camden Town and London group papers to Alfred Thornton, in 1927.

Frank Rutter, foreword to a catalogue, The Camden Town Group: A Review, Leicester Galleries, January–February 1930. Rutter calls his foreword ‘The Camden Town Group. A Fragment of History’.

Gore informed Turner (ibid., p.93): ‘I go to the Alhambra nearly always on Mondays and Tuesdays: 2s. 6d. seats.’

Ibid., p.82a. Victoria Monks, known as ‘John Bull’s Girl’, began her music hall career at the Oxford, in 1903.

The phrase is R.F. Harrod’s. See his excellent chapter ‘Bloomsbury’ in The Life of John Maynard Keynes, 1951.

Collection, Orovida C. Pissarro. Ethel Sands, an American, and Anna Hope Hudson shared a villa near Sickert at Dieppe. They also exhibited together, in June 1912, at the Carfax. Miss Sands specialised in still-life and interiors; Miss Hudson’s subjects seem to have been mainly outdoor scenes. Sickert painted a portrait of her entitled Miss Hudson at Rowlandson House. Both showed their full quota of six works, in 1913–14, at Brighton; Miss Sands, only, was represented at the first London Group exhibition.

Of Renée Finch, Gaudier-Brzeska wrote: ‘I recognize here a greater talent that I have ever met in a woman artist’ (critique in the Egoist – ? June 1914, cited, Ezra Pound, Gaudier-Brzeska: A Memoir, new edn, 1960, p.35); Harald Sund showed four works at Brighton, 1913–14, and three at the first London Group exhibition; Cuthbert Hamilton, a Slade friend of Lewis’s, joined with him in decorating Mme Strindberg’s Cave of the Golden Calf and was a member of the Rebel Art Centre and vorticist group: Edward Wadsworth was then an enthusiastic follower of Lewis too; from a notice of the Carfax show of June 1914, it appears that Squire was a landscape painter of ‘romantic scenes treated unromantically’.

The interview with Gilman appeared in the Standard, 3 February 1914, and as it has not, I think, been quoted since and is of considerable interest, I give it here complete: ‘The principles underlying the formation of this party of artists [London Group] were described to one of our representatives by Mr. Harold J.W. Gilman, the well-known “realist”. “There are at present two well-defined sections in English art”, he said, “which are known as realists and formulists. They both arise from the revolt against naturalism, and they support one another in the sense that one can learn from the other. These sections are combining in ‘The London Group’. There are, of course, artists who cannot be classed wholly with either section, but who constitute a bridge between the two.” He demonstrated with a small cactus in a pot on the table. If he was a formulist, he would simply paint a very obviously heartshaped object with a sort of elliptic circle underneath it to represent the top of the pot and it wouldn’t matter what colour it was. “That is to say, I am rendering so much of it as consists of planes and curves ... On the other hand, if I am a realist I want the object to remain a cactus after I have painted it”.’

Thérèse Lessore was the wife of Bernard Adeney, already a member: in 1926 she married Sickert; Mrs Bevan painted under her maiden name, Stanislawa de Karlowska; Jessie Etchells was the sister of Frederick; Fox Pitt had been friendly with Sickert since 1907.

Manson took great interest in Émile Verpilleux, of Belgian family though London-born: partly perhaps because, like Lucien Pissarro, he practised the art of colour wood engraving.

C.R.W. Nevinson and Wyndham Lewis, in particular. Though there is no reference to his election (one assumes that it followed almost immediately on the decision to increase numbers), Nevinson is in the minutes for 15 November 1913 and 3 January 1914. Here (issue of 6 March 1914) is the Daily News and Leader on the subject: ‘The eccentric ladies and gentlemen who call themselves “the London Group” are holding their first exhibition in the Goupil Gallery, Regent Street. They are “cubists” sans peur et sans reproche, and they claim they are converting not only the world of art, but every man with brains and imagination to the belief that they are men and women of genius ... The picture that will attract most attention is called “The Arrival”, and is the creation of the ingenious young cubist known as C.R.W. Nevinson. Lovely ladies paused before it all yesterday afternoon murmuring “How sweet!” It resembles a Channel steamer after a violent collision with a pier. You detect funnels, smoke, gang-planks, distant hotels, numbers, posters all thrown into the melting-pot, so to speak. Mr. Nevinson acted as interpreter, explaining that it represented a “state of simultaneous mind”. “Isn’t it all just heavenly!” exclaimed the girls. “You see”, said one, “the poor dears have all grown so tired of photography. Their work is in a transitional stage and is naturally rather opaque; but at any rate it’s a welcome escape from impressionism.” A brother cubist is P. Wyndham Lewis. His chef-d’oeuvre is entitled “Christopher Columbus” – which is precisely what you will exclaim when you see it. A crowd tried its best to find the explorer. Mr. Lewis, pointing rapidly to odd corners of the canvas, said: “There’s his head, that’s his leg. Don’t you get me?” It seemed as clear as a London fog. “Our object is to bewilder”, said he; “we want to shock the senses and get you into a condition of mind in which you’ll grasp what our intentions are.” The artists are as quaint as their pictures. They look a cross between the last word in “knuts” and the first word in the students of the Quartier Latin of a quarter of a century ago. They rejoice in being impossible, inconsequent and incoherent, but they say in effect: “We are the fad of the moment. The newspapers may ridicule us, but Society is falling at our feet, and is even paying us to decorate their drawing-rooms.”’

Like Esther, Lucien Pissarro had the highest opinion of Diana White: ‘Now that the sure judgment of my poor dear father is not here’, he wrote, in September 1913, ‘she is the only one I can consult about my paintings’: W.S. Meadmore, Lucien Pissarro. Un Coeur Simple, 1962, p.140.

Dr Irving Epstein, the sculptor’s brother, tells me of Jacob’s passion for the Schubert Lieder. Since Lilian Manson shared this passion and was a professional musician, the two families had more than one interest in common. The music-making began in Paris and continued at the Mansons’ home in Hampstead.

Epstein had a friend, Frank Slade, an artist from Rye, as a caravan-neighbour at Pett. Pissarro describes (letter in the Ashmolean) an amusing occasion with Manson, Epstein, and Slade, that summer.

E.g., catalogue of the London Group. 1914–64 Jubilee Exhibition. Fifty Years of British Art at the Tate Gallery. Also one or two of the short biographies in the Tate Gallery’s catalogue, The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, 2 vols., 1964, to which, however, like everyone concerned with this subject, I am greatly beholden. Sickert, in spite of his early defection, did accept founder-membership of the London Group; whereas none of the following was elected before January 1914: Bomberg, Gaudier-Brzeska, Jessie Etchells, Sylvia Gosse, Thérèse Lessore, John Nash, Walter Taylor, Douglas Fox Pitt: and so they cannot be described (as they often are) as founder-members of 1913.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the University of Hull Art Collection for their permission to reprint this essay first published as ‘“Camden Town” into “London”: Some Intimate Glimpses of the Transition and its Artists, 1911–1914’, the appendix to Malcolm Easton, Art in Britain 1890–1940, exhibition catalogue, University of Hull 1967, pp.60–75.

We are grateful to the University of Hull Art Collection for their permission to reprint this essay first published as ‘“Camden Town” into “London”: Some Intimate Glimpses of the Transition and its Artists, 1911–1914’, the appendix to Malcolm Easton, Art in Britain 1890–1940, exhibition catalogue, University of Hull 1967, pp.60–75.

Malcolm Easton was Senior Lecturer in the History of Art, University of Hull and Founder and Honorary Curator of the University of Hull Art Collection. He died in 1993.

How to cite

Malcolm Easton, ‘The Camden Town Group into the London Group: Some Intimate Glimpses of the Transition 1911–14’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www