Robert Bevan Haze over the Valley c.1913

Robert Bevan,

Haze over the Valley

c.1913

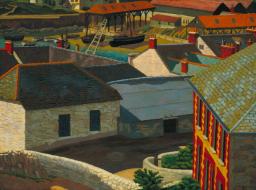

Bevan’s painting shows the view north from the Blackdown Hills on the Devon and Somerset border. It was made when the artist was staying at his friend’s farm, Applehayes, with other Camden Town Group artists. The geometric pattern of cottages and pale grid of fields fading into the horizon are the only indication of human intervention in the landscape. Painted in a heavy impasto, the work is striking for its colour, design and rhythm rather than traditional elements of the picturesque.

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

Haze over the Valley

c.1913

Oil paint on canvas

432 x 533 mm

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1959

T00282

c.1913

Oil paint on canvas

432 x 533 mm

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1959

T00282

Ownership history

Inherited by Stanislawa de Karlowska (1876–1952), the artist’s wife, who between 1925 and 1929 gave it to her son, Robert Alexander Bevan (1901–1974); purchased from P. & D. Colnaghi & Co. Ltd., London, by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest and presented to Tate Gallery 1959.

Exhibition history

1960

One Hundred and Ninety Second Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts, Royal Academy, London, April–August 1960 (265).

1965

Robert Bevan 1865–1925: Centenary Exhibition, P. & D. Colnaghi & Co. Ltd., London, March–April 1965 (31).

1965

Centenary Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings and Lithographs by Robert Bevan 1865–1925, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, April–May 1965 (31).

1975–88

Bradford City Art Gallery, September 1975–September 1988 (long loan).

1998

Going Modern and Being British: Art Architecture and Design in Devon 1910–1960, Royal Albert Memorial Hall, Exeter, April–May 1998, City Museum and Art Gallery, Plymouth, June–July 1998 (no catalogue).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (85, reproduced).

References

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, p.56.

1965

R.A. Bevan, Robert Bevan 1865–1925: A Memoir by his Son, London 1965, p.27.

1975

Geoffrey Grigson, Britain Observed: The Landscape through the Artists’ Eyes, London 1975, p.164, reproduced pl.128.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, p.363.

1984

Jonathan Benington, ‘Robert Bevan, Dunn’s Cottage and Applehayes’, Leeds Art Calendar, no.94, 1984, pp.15, 18, reproduced pl.14.

1986

Rosalind Billingham, Artists at Applehayes: Camden Town Painters at a West Country Farm 1909–1924, exhibition catalogue, Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry 1986, p.29, reproduced p.26.

1999

Frances Stenlake, From Cuckfield to Camden Town: The Story of Artist Robert Bevan, Cuckfield 1999, p.57.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.163.

Technique and condition

Haze over the Valley is painted in artists’ oil paints on a primed and stretched canvas. The canvas consists of one piece of plain, open-weave cloth, probably linen, with uneven threads, which was primed before being stretched. There is little evidence that the canvas was sized before the application of a substantial creamy priming layer that covers most of the canvas. The priming was sufficiently fluid during application to penetrate to the back of the canvas. The canvas texture is retained and has an irregular fibrous character providing a painting surface with substantial tooth. It is possible that the artist prepared the canvas himself.

The primed canvas is attached to a pine stretcher which is probably original. However, the canvas has been re-stretched, the original thumb tacks used by Bevan having been replaced with ‘blued’ ferrous tacks. The holes and marks left by the thumb tacks remain in the tacking margins as vacant holes. The canvas has slight distortions and is poorly tensioned. This is because the structure of the canvas was made stiff by its saturation with priming.

The outlines of the trees and buildings are sketched in blue paint although the rest of the landscape reveals little sign of initial drawing (see also Tate N05911). The thick but malleable colour is applied with vigorous brushstrokes often leaving broken areas of priming showing, especially around the blue outlines in which the colours are approximately contained. In many areas there is only one application of colour or a couple of intermingled layers of rich colour applied wet-in-wet. The paint retains the imprint of the brush and complex impastos capture its rapid and emphatic handling. The swirls of rhythmic brushwork used to describe the trees rise vertically against the predominantly horizontal brushwork of the land and sky. Some areas of colour towards the bottom exhibit pinholes from aeration of the paint which add to the complex topography of the painting’s impasto.

The painting extends slightly over the top and two side edges, the paint and ground are cracked and flaking along the angle of the tacking edges, where it has been re-stretched after the paint had become brittle. The painting has had a soft resin varnish applied to it, which penetrates the cracks and small losses around the edges indicating that it was applied after the canvas had been re-stretched. The varnish flowed into the texture of the paint forming small puddles in the hollows that appear yellow (see also Tate N04750).

Roy Perry

November 2003

How to cite

Roy Perry, 'Technique and Condition', November 2003, in Robert Upstone, ‘Haze over the Valley c.1913 by Robert Bevan’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

Bevan painted Haze over the Valley while he was staying at Applehayes, a farm near Clayhidon in the Blackdown Hills in Devon, close to the border with Somerset.1 Here he was the guest of Harold Bertram Harrison (1855–1924), a landowner, amateur artist and writer. Born at Waterhouse, a country house at Monkton Combe near Bath, Harrison spent his working life until the age of forty-one with his brother on the family ranch, La Isleta, in Argentina. When he returned to England, however, Harrison pursued his interests in art, and in 1896 enrolled at the Slade. Studying there until 1898 his fellow students included Spencer Gore, who started the same year, Harold Gilman and Gwen and Augustus John. Harrison acquired the Applehayes estate in 1909 and by buying the adjacent land of Barn Farm, Little Garlandhayes and Lears Farm he considerably extended his holding to around 300 acres. He built a series of seven trout ponds, fed by a tributary of the River Culm, and rode to hounds as well as farming the estate. Applehayes itself was a traditional Devon longhouse, which dated back to around 1550, but Harrison added a special studio wing for his artist guests, that included two bachelor bedrooms. Harrison’s drawing teacher at the Slade had been Henry Tonks (1862–1937), and he evidently maintained their friendship for, when he moved to Applehayes, he sought his advice as to whom among the younger generation of artists he might entertain there.2

Gore was the first of the future Camden Town Group artists to visit, in 1909, and it seems evident that they were already on friendly terms (he started the same year at the Slade as Harrison). Their friendship evidently flourished after this first visit, and when the Gores’ first child Elizabeth was born in 1912 they chose Harrison to be her godfather. When Harrison died in 1924 he bequeathed the contents of his apartment at 1 Stanhope Gardens in South Kensington to Gore’s widow Mollie, and left £1,000 to his godchild. Gore returned to Applehayes in 1910, and again in 1913, this time joining Bevan and Charles Ginner. Bevan himself stayed with Harrison for the first time in 1912, in the company of Ginner (fig.1), and brought his wife Stanislawa de Karlowska, who accompanied him there in 1913 and on his last visit in 1915. Gilman appears never to have visited Applehayes. Other much younger painters Harrison entertained included Mark Gertler (1891–1939), William Roberts (1895–1980) and Stanley Spencer (1891–1959). ‘In the summer of 1911’, Roberts wrote,

three Slade students were invited to stay a month, alternately ... Gertler, the first to go, chose July; when his month ended, Spencer followed, in August; while I, the last on the list had September. A country mansion would well describe Harrison’s place with its stables for hunters, and numerous domestic staff. Harrison had his brother and two nephews staying with him.3

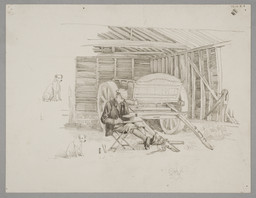

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Landscape with Farmhouses 1912–13

Oil paint on canvas

512 x 687 mm

Manchester City Galleries

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Manchester City Galleries

Fig.1

Charles Ginner

Landscape with Farmhouses 1912–13

Manchester City Galleries

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Manchester City Galleries

Subject and style

In Haze over the Valley Bevan showed the view looking north from a ridge near Applehayes, and looking down onto some buildings known as Dunn’s Cottages, where Harrison’s chauffeur lived. It was a spot to which Bevan returned repeatedly, and there are a number of pictures of the view. The closest in standpoint and composition is A Devonshire Valley 1913 (fig.2), while Little Oak Tree 1915 (King George VI Art Gallery, Port Elizabeth, South Africa),6 originally titled The Back of Dunn’s Cottage, views the scene from a point slightly further to the right than the Tate picture. Bevan also painted the houses from down on the road below in Dunn’s Cottage 1915 (fig.3), a close-up view with a man forking over a dung heap in the foreground, and another view from the road looking back, Dunn’s Cottage, near Applehayes 1915 (private collection).7

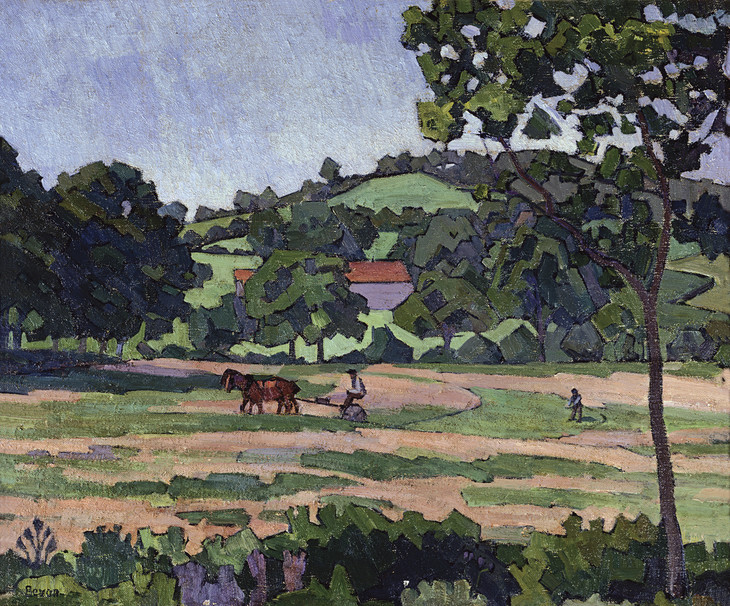

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

A Devonshire Valley 1913

Oil paint on canvas

51 x 61 cm

Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter

Photo © Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.2

Robert Bevan

A Devonshire Valley 1913

Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter

Photo © Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

Dunn’s Cottage 1915

Oil paint on canvas

482 x 558 mm

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.3

Robert Bevan

Dunn’s Cottage 1915

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

There are composition sketches for Dunn’s Cottage in one of Bevan’s unfoliated sketchbooks in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford,8 and it is likely that Haze over the Valley was similarly based on a drawing made on the spot and then painted away from the scene, perhaps in the studio at Applehayes. In the last fifteen years of his life Bevan painted numerous pictures which show an assimilation of buildings into the landscape. Usually these are scenes without figures, in which a human presence is denoted only by the existence of houses or farm buildings, and the agricultural taming and moulding of the landscape itself. In Haze over the Valley, as in other landscapes, Bevan consciously simplified the forms. The geometric planes of the buildings act as a satisfying foil to the looser irregular rhythm of the trees and vegetation, whilst echoing the grid of fields in the background. With this lack of scenic elements, spectacular natural features, or artificially constructed rustic incident, Bevan rejected traditional notions of picturesque landscape painting. It suggests that while he was recording directly his immediate surroundings, he was also using them to create an image which relied on colour, design and rhythm for its impact. Richly painted, the colours have been applied thickly and have a pronounced, mosaic-like impasto. Bevan has grouped his colours together, but there are also sudden jumps out of harmony, such as on the top of the roof where the sunlight catches it. Although each area of colour is modulated, the colours come together to form flat areas of an almost post-cubist character, creating an abstract design of their own, separate to their subject. But unlike Fauve painting where each part of the picture is painted with equal colour value, Bevan has employed aerial perspective, where the colours fade towards the background to suggest distance and a sense of recession toward the horizon.

The prevalent combination of mauve and green may be due to the influence of Gore, who used the pairing extensively in urban scenes around this time, such as, for instance, Houghton Place 1912 (Tate N03839) and The Fig Tree 1912 (Tate T00028) and Letchworth landscapes such as The Cinder Path 1912 (Tate T01960). Bevan stayed at Applehayes at the same time as Gore on his 1913 visit, when Haze over the Valley was most likely to have been painted. Increasingly, the two painters came to share stylistic affinities, of colouring and most closely in their stylisation of landscape forms. This reached its strongest expression in Gore’s work in his series of pictures of Letchworth in 1912, where hedges, trees and clouds are all drawn with exaggerated straight or jagged edges. Bevan owned a landscape by Gore, Croft’s Lane, Letchworth 1912 (private collection),9 and it appears that he may have been influenced by Gore’s adoption of this style of drawing. However, Bevan had an existing preoccupation with the interdependent relationship of forms and their structure. This stylistic development in his work towards a strengthening of pattern was a natural and logical progression, and its roots are felt in pictures such as Horse Sale at the Barbican 1912 (Tate N04750) in the pattern-making of the crowd of figures. While this development was no doubt influenced partly by Gore, it was also something which must be attributable to Bevan seeing works by Paul Cézanne in London at Roger Fry’s post-impressionist exhibitions of 1910 and 1912, and on his visits to Paris en route to Poland.

When Bevan visited Applehayes the region was still a very traditional agricultural society. Devon and Somerset were often popularly portrayed as being quintessentially English, where the impact of modern life, industrialisation, urban expansion, technology and the like were not so strongly felt. As an agrarian society it was a region which represented for the Edwardian imagination a link to a mythologised, traditional past, which seemed to embody elements of English identity connected with land and its bountiful cultivation, alongside a sense of the wildness of the natural landscape. It was certainly true that the region was less touched by modernity, and after the end of the First World War it was exactly this attribute that started a boom in tourism which has continued to this day, and which essentially compromised the reality of the West of England being a haven of isolation from the modern world.10 Bevan may well have felt a certain attraction to the rolling landscape of the Blackdown Hills and its farms, perhaps making comparisons with the Sussex downland of his youth. On one level Bevan was following a traditional genre of landscape painting in Haze over the Valley. But there seems an extra radicalism to painting the landscape in such a stylised way, and in an area which was conservatively characterised by its tradition and ‘Englishness’. The presence of Bevan, Gore and Ginner at Applehayes seems to represent the coming of Camden Town to the country, the penetration of the natural and traditional by an avant-garde associated with modernity and the life of the city. Interestingly, Bevan’s fascination with London’s horses is a similar phenomenon in reverse, by representing animals more usually associated with the countryside being used to serve the city.

Robert Bevan and Stanislawa de Karlowska standing outside Lytchetts in Devon c.1917–18

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Fig.4

Robert Bevan and Stanislawa de Karlowska standing outside Lytchetts in Devon c.1917–18

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

The Hay Harvest 1916

Oil paint on canvas

520 x 620 mm

Private collection

Photo © Tate

Fig.5

Robert Bevan

The Hay Harvest 1916

Private collection

Photo © Tate

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

The Chestnut Tree 1916

Oil paint on canvas

500 x 600 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.6

Robert Bevan

The Chestnut Tree 1916

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Robert Bevan sketching, possibly on the Blackdown Hills, Devon c.1917–18

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Fig.7

Robert Bevan sketching, possibly on the Blackdown Hills, Devon c.1917–18

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Bevan exhibited a number of Blackdown Hill pictures at the Goupil Gallery Salon and London Group between 1913 and 1916, but it is not possible to identify this one, and it may never have been shown as it was never sold. The artist’s son R.A. Bevan wrote about Haze over the Valley to the Tate Gallery in 1960:

I honestly don’t know whether the picture the Chantrey Bequest have bought was ever exhibited. It was off its stretcher when my Father died, and I only had it re-stretched and framed a few years ago. I am afraid the title is one I had to give it myself because of the limited range of actual titles, since he often painted the same place in different conditions of light etc. The title seemed, however, to be quite descriptive.11

Bevan visited Applehayes for the last time in 1915. ‘Because of wartime conditions’, Bevan’s son wrote, ‘it was no longer possible for Harrison to continue his open hospitality to artists.’12 But Bevan felt a strong affinity for the area, and continued to spend extended periods there until the end of his life. From 1916 to 1919 he spent a large part of every year at a cottage called Lytchetts in the Bolham Valley in the heart of the Blackdown Hills (fig.4), painting works such as The Hay Harvest 1916 (fig.5) and The Chestnut Tree 1916 (fig.6). However, it was very different from the bonhomie and life of plenty at Applehayes. Separated from his family in London for much of the time, Bevan’s existence here was ascetic and solitary (fig.7). His son recalled:

At Lytchetts he was able to have a long working summer, going down early in May and often staying till the middle of November ... The cottage was new and dry, well lit, and very barely furnished. His wife would join him for about six weeks during the school holidays, and sometimes my sister and I would share this spartan existence for two or three weeks at a time. But at Lytchetts ... he was mostly alone, walking sometimes a long way afield to draw his subjects and coming back to paint them in the bare unfurnished rooms which served as his studios.13

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

Information about Applehayes and Harrison is from Clayhidon Local History Group and Artists at Applehayes: Camden Town Painters at a West Country Farm 1909–1924, exhibition catalogue, Herbert Art Gallery, Coventry 1986.

William Roberts, ‘A Sketch of His Early Life’, in Five Posthumous Essays and Other Writings, Valencia 1982, p.79. Roberts refers to his host incorrectly as ‘Frederick’ Harrison.

Reproduced in Jonathan Benington, ‘Robert Bevan, Dunn’s Cottage and Applehayes’, Leeds Art Calendar, no.94, 1984, p.16.

Reproduced in Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1983 (24).

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

Related archive items

-

Photograph

-

Grouped items

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘Haze over the Valley c.1913 by Robert Bevan’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www