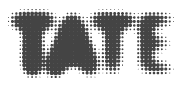

Bevan made a number of crayon and watercolour studies of farmworkers ploughing while staying in the artists’ colony at Pont-Aven in Brittany. Using bright post-impressionist colours and swirling lines, this picture depicts a woman in regional dress leading a pair of Ardenne horses, which are followed by a male figure pushing a wooden swing plough.

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

Ploughing in Brittany

1893

Conté crayon and watercolour on paper

256 x 352 mm

Stamped with monogram ‘R P B’ and inscribed by the artist ‘31’ in pencil bottom right

1893

Conté crayon and watercolour on paper

256 x 352 mm

Stamped with monogram ‘R P B’ and inscribed by the artist ‘31’ in pencil bottom right

Purchased (Grant-in-Aid) 1959

T00250

T00250

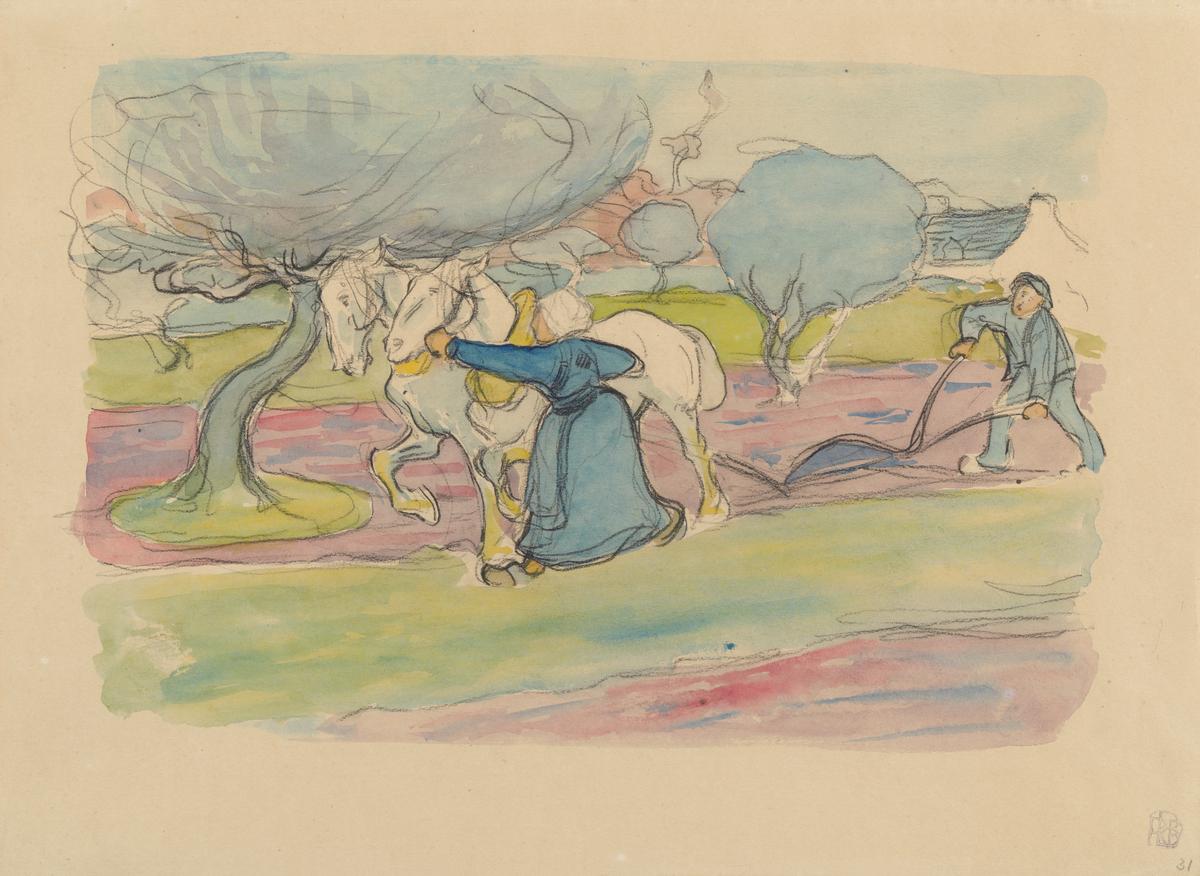

Verso:

Study of a Woman

1893

Conté crayon on paper

Inscribed by the artist ‘ANNA’ top right

Study of a Woman

1893

Conté crayon on paper

Inscribed by the artist ‘ANNA’ top right

Ownership history

Inherited by Stanislawa de Karlowksa (1876–1952), the artist’s wife; given in the 1920s to the artist’s son, Robert Alexander Bevan (1901–1974); P. & D. Colnaghi & Co. Ltd., London, from whom purchased by Tate Gallery 1959.

Exhibition history

1959

Exhibition of Drawings and Lithographs by Robert Bevan 1865–1925, P. & D. Colnaghi & Co. Ltd., London, March 1959 (38, 20 guineas).

1992–3

Beardsley to Bomberg: British Drawings and Watercolours 1870–1920, Tate Gallery, London, November 1992–February 1993 (no number).

References

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, pp.55–6.

1965

R.A. Bevan, Robert Bevan 1865–1925: A Memoir by his Son, London 1965, p.27.

2008

Frances Stenlake, Robert Bevan: From Gauguin to Camden Town, London 2008, p.38.

2011

Helena Bonett, ‘“In these English farms, if anywhere, one might see life steadily and see it whole”: Representations of the Countryside in E.M. Forster’s “Howards End” and the Paintings of Robert Bevan’, The Camden Town Group, Tate 2011, http://www.tate.org.uk/.

Technique and condition

The wove buff-coloured paper is machine made and of medium weight. Four edges of the sheet are cut straight. In Ploughing in Brittany, Bevan has left uniform blank margins around the perimeter so the composition does not cover the full extent of the paper. The majority of the image was first drawn with Conté crayon after which watercolour was applied. A number of additional Conté crayon lines appear to have been added after the application of the watercolour to emphasise certain features. Generally the watercolour has been applied within the outlined shapes of the drawing. Bevan appears to have applied pure colour to the paper and, where there is more than one colour, this has been built up in successive layers.1 The ‘white’ areas of the image, such as the pair of horses and the hat of the woman leading them, are suggested by allowing the blank paper to show through.

Kate Jennings

June 2005

Notes

How to cite

Kate Jennings, 'Technique and Condition', June 2005, in Robert Upstone, ‘Ploughing in Brittany 1893 by Robert Bevan’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

Of all the Camden Town Group members, except Walter Sickert and Lucien Pissarro, Robert Bevan had the greatest first-hand experience of French painting and painters. He was of a slightly older generation than Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore, and was able to glean a more immediate knowledge of recent impressionist and post-impressionist developments on the continent. Bevan received a year’s training at the Westminster School of Art in Vincent Square SW1 under Frederick Brown (1851–1941), but in autumn 1889 he travelled to Paris to enroll at the Académie Julian. This was a popular choice among British and American art students who, in increasing numbers during the 1880s, came to study in Paris to finish their training. The jolly bohemian life to be found there was the setting for George du Maurier’s popular novel Trilby of 1894, but the choice to study in Paris was also the result of serious dissatisfaction with London teaching and academic values. In Britain there was a strong feeling among the younger generation of artists and art students that the restrictive influence of the Royal Academy was holding back the development of British art, and that the Academy’s teaching methods were outmoded and irrelevant.1 At Julian’s – named after the proprietor of the school who was a retired circus strong-man and sometime prize-fighter – students were allowed immediately to draw from the figure and the nude, something prohibited in the Royal Academy Schools until several years’ study had been accumulated. William Rothenstein, a student at Julian’s from 1888–9, gave a vivid account of life in the art school:

The Académie Julian was a congeries of studios crowded with students, the walls thick with palette scrapings, hot, airless and extremely noisy. The new students were greeted with cries, with personal comments calculated, had we understood them, to make us blush ... Julian himself knew nothing of the arts. He had persuaded a number of well-known painters and sculptors to act as visiting professors, and the Académie Julian became, after the Beaux-Arts, the largest and most renowned of the Paris schools ... At the Académie there were no rules, and, save for a massier in each studio who was expected to prevent flagrant disorder, there was no discipline ... Over the entrance to the studios were written Ingres’ words ‘Le dessin est la probité de l’art’ [Drawing is the integrity of art]; and ‘Cherchez le caractère dans la nature’ [Look for character in nature].2

Importantly, Julian’s offered a truly international experience and Rothenstein noted ‘Russians, Turks, Egyptians, Serbs, Roumanians, Finns, Swedes, Germans, Englishmen and Scotchmen, and many Americans, besides a great number of Frenchmen’.3 While Bevan was at the school the 1889 Exposition Universelle was held in Paris, running from May to November. As a snapshot of the co-existence of different generations and styles it was the Pre-Raphaelite Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898) who was hailed as the great revelation of the show, but in the British section Bevan would have been able to also see Sickert’s small impressionist picture The October Sun, now generally known as The Red Shop c.1888 (Norwich Castle Museum).4 Elsewhere Bevan could see much more exciting and cutting-edge material. Pictures by Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Vincent van Gogh were on view in September that year at the Fifth Salon des Indépendants. However, potentially it might have been the small independent exhibition held in the Café Volpini on the periphery of the Exposition Universelle showground that could have had the greatest impact on Bevan, although it cannot be known for certain that he saw it. Here Paul Gauguin and Claude-Émile Schuffenecker organised the first showing of the ‘Groupe Impressioniste et Synthétiste’, a selection of work by their circle in Pont-Aven. These included various prints and drawings of Breton peasant life and the local landscape, and it may have been these that stimulated Bevan’s subsequent interest in printmaking. If he did not see the small exhibition, he may at the least have heard about it; what is certain is that among his contacts in Paris and in the Académie Julian, Bevan would have been well aware of the artists’ colony at Pont-Aven, and that a set of painters had grouped themselves there around Gauguin.

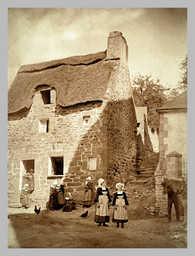

Pont-Aven

Bevan’s studies at the Académie Julian ended in the early summer of 1890, and he returned briefly to England. But by August he was in place in Pont-Aven, along with his painter-friend and exact contemporary Eric Forbes-Robertson (1865–1935), and he remained there until the following year, and also returned in 1893–4. Pont-Aven in Brittany had been an artists’ colony since the 1860s, when a small group of American painters settled there to work. By the 1880s the town had become a thriving community of disparate artists who were drawn to the picturesque landscape and people of Brittany. Gauguin spent three periods there – 1886, 1888–91 and 1894 – and based his pictures around Breton costumes and customs, works which took on an increasingly rich colouring and symbolist character.

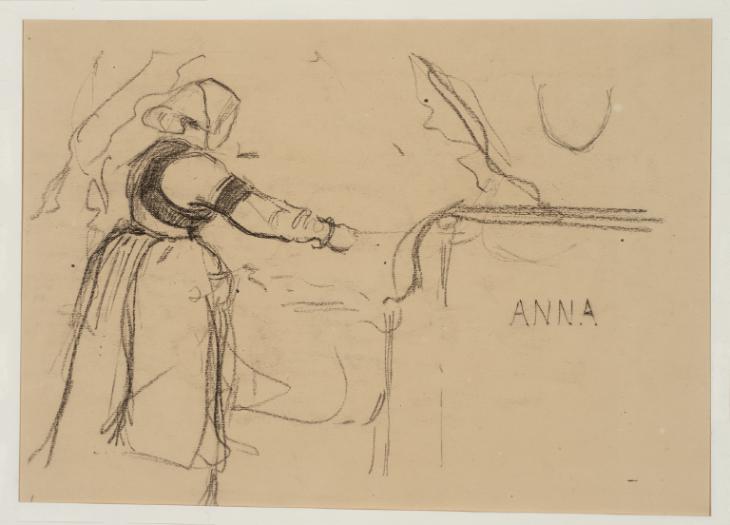

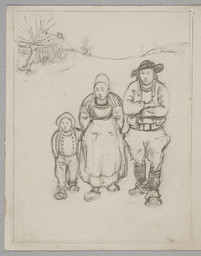

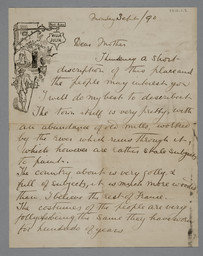

Bevan wrote to his mother Laura about his impressions and interests in the area in a long letter dated September 1890, which is interspersed with illustrations of the local peasants’ costumes (fig.1). Bevan wrote this from the Villa Julia, where he was staying; his mention in explaining the local costume of ‘with the aid of the Hotel’ is because the letterhead illustrates some Breton peasants in traditional dress. ‘Julia’s’ was a Pont-Aven institution opened by Julia Guillou (1848–1927) that catered specifically for painter guests, and was a popular and well-known place to stay, eventually even starting its own art classes.

In the letter to his mother Bevan almost supplies an inventory of the rural crafts that he has seen in Pont-Aven. This was perhaps partly the response of someone who grew up in Sussex at a time when its character was distinctly rural. The 1880s and 1890s in Britain saw the flowering of rural naturalist painting, its chief exponents being George Clausen, Henry Herbert La Thangue and Alexander Stanhope Forbes. Their pictures commemorated traditional crafts at the very moment of their decline, and the commensurate modernisation and mechanisation of agricultural practice, and the encroachment of the cities into the countryside. By contrast, Pont-Aven was famed for its traditional culture and practices, although it was also linked to Paris by railway and by the time Bevan stayed there had established a thriving economy based on tourism. Agriculturally and industrially Brittany was in a period of transition, and the stereotypical view of the region in this period as being either primitive or backward has been vigorously challenged.5 Nevertheless, it was the mythic ideal of an unspoilt rurality and traditional culture rooted in the land that attracted visitors, and which the tourist trade of Pont-Aven was keen to encourage.

After a spell in Tangier, Bevan returned to Pont-Aven in 1893 and remained there until the following year. It was on this trip that he made a series of studies in charcoal crayon, often washed with watercolour, of different rural activities. These include The Flail c.1893 (private collection),6 Sabot Makers c.1893 (private collection),7 and Threshing c.1893.8 But ploughing seems to have been a particular source of interest, and Bevan made a number of such studies of the activity. These can be related to his lithograph The Plough 1893–4,9 and also with his unfinished oil The Dawn Harrow, Brittany c.1894 (private collection).10 It is possible that the group of watercolours were dry runs for choosing compositions for these works.

Subject and composition

It appears that Ploughing in Brittany was once a page in Bevan’s sketchbook, as it is numbered in the corner. The woman wears characteristic local costume, including a coiffe headdress, the form of which varied depending on the wearer’s age, social position and family connection. As the trees are still in leaf, it is likely that Bevan shows an autumn ploughing scene, making 1893 the likely date of the drawing. The plough itself appears to be a traditional wooden type with two wooden handles and a central, horizontal wooden beam. It has no wheel at the front and so is termed a swing plough. It is drawn by two compact grey horses of the Ardennes type, a smaller version of the familiar English Shire horse. As the plough is being drawn by only a pair of horses it is possible to gauge that this is fairly light soil. Bevan shows the pair being led by the woman; this was common practice when a larger team of four or six horses were used, or oxen, but for a pair it was unusual. Normally two horses would be controlled by the ploughman alone using a system of spoken commands and leading reins which ran back to the plough handles.11 The slightly anomalous presence of a second figure raises the possibility that the plough team was modelling for the artist, and reflects a pose for his convenience rather than a snap-shot of actual rural life. There is evidence to suggest that there was a degree of self-consciousness in the local Breton population’s interactions with their artist visitors,12 and Bevan’s letter to his mother, where he reveals that he was a spectator at a sea-borne ceremony, reinforces that sense of the artist as audience.

Bevan made three closely related watercolours that show the same spot. In Ploughing, Pont Aven c.1893–4 (private collection),13 the plough is seen slightly nearer the cottage, although it is operated here only by a single male figure; the pair of trees in the drawing is the same as those most prominent in Ploughing in Brittany. In Ploughing c.1893 (private collection),14 Bevan shows the plough team going away from him, as if they have just passed, and the trees and cottage are again recognisible. The figure leading the team here, however, wears a hat and appears to be a man. Made on paper the same size and type as Tate’s drawing, Paysan Breton au Labourage c.1893–4 (private collection)15 probably came from the same sketchbook. This shows the plough head on, with again only a single figure, and a single horse. The tree in this picture is identifiable as the one on the left in Ploughing in Brittany. The exact location of all these scenes is impossible to identify, but it is most certainly in the area surrounding Pont-Aven. The sequential nature of the studies, showing the plough team from different angles and at different points in the field must suggest they were made within a short space of time.

The drawing’s flattened shapes and flowing, rhythmic pencil lines can be linked stylistically with the Synthetism developed by Gauguin and his circle. Bevan met Gauguin in Pont-Aven in 1894 and, although they do not appear to have become particularly close friends, the French artist dedicated his 1894 monotype Two Standing Tahitian Women ‘à l’ami Bavan [sic]’.16 One of Bevan’s unfoliated Pont-Aven sketchbooks held by the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, appears to contain a portrait drawing of Gauguin.17 The style of Ploughing in Brittany also seems to have a strong echo of van Gogh, and Bevan’s son believed he was a source of inspiration for his father, although the two artists never met.18 While at Pont-Aven Bevan also met Auguste Renoir, ‘who is said to have given generous encouragement, especially for his drawings and paintings of horses’.19

On the back of the sheet is a drawing of a Pont-Aven girl. She appears to be making a bed or straightening a counterpane, and it is likely that she is one of the staff at Julia’s preparing Bevan’s room. He has inscribed her name – ‘Anna’ – on the page. Showing the girl at work seems partly an extension of Bevan’s recording of the life of Pont-Aven around him, principally tasks related to the agrarian economy. But in showing a servant-girl in his bedroom, there inevitably also seems to be a distant but distinct frisson of impropriety. The world of the demi-mondaine would have been familiar to Bevan from Paris, the waitress, the seamstress and chambermaid all crossing, through force of economic circumstances, into prostitution and modelling for artists, and the latter seeming rather likely here given the establishment of an art school in the hotel.

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

See Robert Upstone, ‘Between Innovation and Tradition: Waterhouse and Modern French Painting’, in John William Waterhouse: The Modern Pre-Raphaelite, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 2009, pp.37–49.

William Rothenstein, Men and Memories: Recollections of William Rothenstein 1872–1900, London 1931, pp.36, 39, 40.

See Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, ‘Les Données Bretonnantes: La Prairie de représentation’, Art History, vol.3, no.3, 1980, pp.314–44.

Graham Dry, Robert Bevan 1865–1925: Catalogue Raisonné of the Lithographs and Other Prints, London 1968, no.7; reproduced in Stenlake 2008, p.38.

This and previous information supplied by Roy Brigden, Keeper, Museum of English Rural Life, University of Reading.

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘Ploughing in Brittany 1893 by Robert Bevan’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www