Spencer Gore From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond 1913

Spencer Gore,

From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond

1913

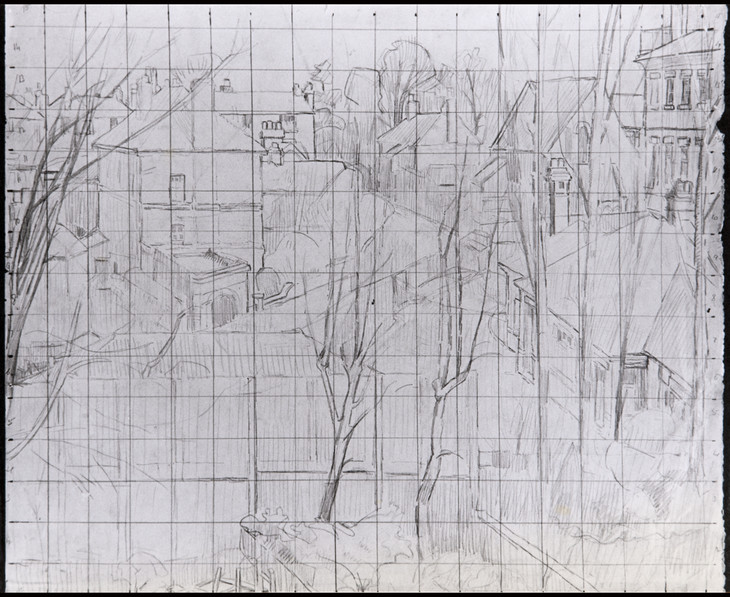

This painting shows the view from a top-floor window at the rear of 6 Cambrian Road, Richmond, where the Gore family relocated in 1913. The visible transfer grid underneath the thin paint reveals Gore’s process of painting from squared-up studies. Colour is loosely applied without gradation to create stylised forms within a flattened pictorial space. Chosen to illustrate his obituary in the vorticist periodical Blast, this may be the last picture Gore worked on before his early death from pneumonia.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond

1913

Oil paint on canvas

559 x 686 mm

Inscribed studio stamp ‘S.F. GORE’ bottom right

Presented by subscribers 1920

N03558

1913

Oil paint on canvas

559 x 686 mm

Inscribed studio stamp ‘S.F. GORE’ bottom right

Presented by subscribers 1920

N03558

Ownership history

Mrs Mary Johanna Gore, the artist’s widow; bought by an anonymous group of subscribers and presented to Tate Gallery 1920.

Exhibition history

1920

Paintings by the Late Spencer F. Gore, Paterson and Carfax Gallery, London, October 1920 (20, as ‘In Richmond No.1’).

1996–7

Spencer Gore in Richmond, Museum of Richmond, September 1996–January 1997 (no number, reproduced p.23).

2004

Art of the Garden: The Garden in British Art, 1800 to the Present Day, Tate Britain, London, June–August 2004, Ulster Museum, Belfast, October 2004–February 2005, Manchester Art Gallery, March–May 2005 (11, reproduced).

References

1914

Blast, no.1, June 1914, reproduced pl.XX.

1929

James Bolivar Manson, The Tate Gallery, London 1929, p.141.

1962

John Rothenstein, The Tate Gallery, London 1962, p.254.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, p.245, reproduced pl.XI.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, p.375.

1985

David Bindman (ed.), The Thames and Hudson Dictionary of British Art, London 1985, reproduced p.105.

1998

Lucien Pissarro et le post-impressionisme anglais, exhibition catalogue, Musée de Pontoise 1998, p.76, reproduced p.75.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.182.

2002

David Peters Corbett, ‘The Geography of Blast: Landscape, Modernity and English Painting, 1914–1930’, in David Peters Corbett, Ysanne Holt and Fiona Russell (eds.), The Geographies of Englishness: Landscape and the National Past, 1880–1940, New Haven and London 2002, pp.120–1, reproduced fig.47.

2004

David Peters Corbett, ‘The Aesthetics of Materiality: English Modernism before 1914’, The World in Paint: Modern Art and Visuality in England, 1848–1914, Manchester 2004, p.247, reproduced fig.91, p.248.

Technique and condition

From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond is painted in artists’ oil paints on primed stretched canvas. The cloth appears to be linen and has a plain open weave. The support was supplied by the artists’ colourman George Rowney & Co. (now Daler-Rowney) and is a ‘Quality B’ grade canvas: ‘a good quality British Canvas with a light back’.1 The cloth has been sized and primed, probably with a lead white and oil-based priming.2 It is evenly applied and retains the canvas weave texture. The primed canvas is attached to a four-member stretcher with the steel tacks in their original positions.

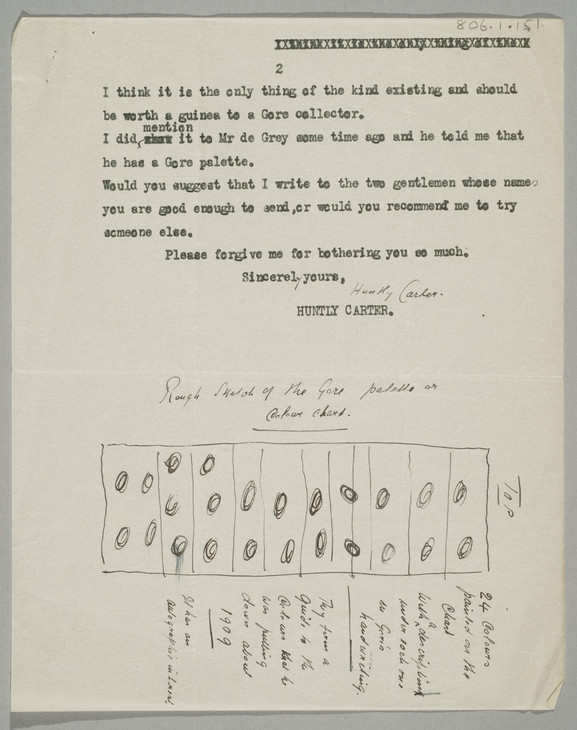

Huntly Carter died 1942

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 17 April 1935

Tate Archive TGA 806/1/151

© Estate of Huntly Carter

Fig.1

Huntly Carter

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 17 April 1935

Tate Archive TGA 806/1/151

© Estate of Huntly Carter

Roy Perry

April 2004

Revised by Sarah Morgan

June 2006

Notes

How to cite

Roy Perry, 'Technique and Condition', April 2004, revised by Sarah Morgan, June 2006, in Robert Upstone, ‘From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond 1913 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

In the early summer of 1913 Spencer Gore, his wife Mollie and baby daughter Elizabeth moved from their flat in Houghton Place, Mornington Crescent, to 6 Cambrian Road, Richmond. Mollie was pregnant with their son Frederick, who was born in November 1913, and the move must have been precipitated by a need for more space and also a desire for a healthier environment, away from the smoky position of Houghton Place between the railways lines. At Cambrian Road the family had a whole house, in a pleasant road in a leafy, residential area of the town (fig.1). Another attraction must have been the proximity of Richmond Park, with access through the Cambrian Gate at the end of the street, barely 100 yards away.

At their new home, Gore immediately revived his practice of painting views from the front and back of the house. In From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond, Gore shows the view from a top-floor window at the rear. Many of the buildings visible were part of a hospital in Grove Road. The whole area has now been redeveloped and looks very different, but some of the buildings on the right, perhaps ward blocks, are still present. The bare branches of the trees in the foreground suggest that this must be a late autumn or early winter scene.

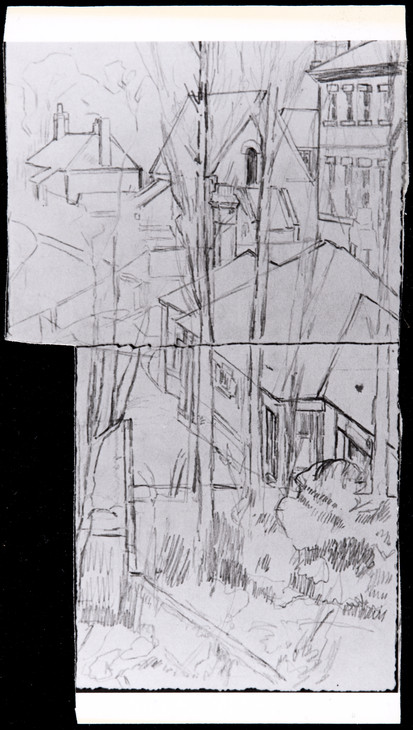

The paint is very thinly applied and the squaring-up shows through clearly, indicating the picture is not finished. A very similar composition, but with a slightly different view suggesting it was painted from another rear window, belonged to Gore’s friend Robert Bevan (private collection).1 This slightly smaller picture has a more subdued palette to the Tate work, and the paint is more thickly and richly applied. It may have been that Gore was intending to return to the Tate painting to complete it. However, the picture shows evidence of Gore continuing the modernist approach he had developed at Letchworth, stylising forms and using areas of flat colour (see Tate T01859). Indeed, the whole scene is ‘flattened’ out; there is no attempt to create an impression of recession and this is apparently a quite deliberate action, rather than a symptom of its incomplete state. Two studies for the painting survive: a graphite and blue pencil drawing on wove paper that has been torn carefully into three pieces (two pieces shown in fig.2),2 and a squared-up and numbered graphite and blue pencil drawing on wove paper of the whole composition on a single sheet, from which the oil must have been transferred (fig.3). Gore’s normal procedure when making a painting was either to stand in front of his subject and paint direct, or else to make careful drawings and then execute the oil in his studio, as in the present case.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Study for 'From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond' 1913

Graphite and blue pencil on paper

188 x 220 mm, 190 x 262 mm

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Fig.2

Spencer Gore

Study for 'From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond' 1913

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Study for 'From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond' 1913

Graphite and blue pencil on paper

223 x 197 mm

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Fig.3

Spencer Gore

Study for 'From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond' 1913

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

When Gore died, his friend Wyndham Lewis used From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond to illustrate his obituary in Blast.3 This may seem a somewhat unusual choice, as it was unfinished. Lewis may have chosen it because he felt it was so technically advanced or possibly because it was the last picture Gore was working on before his death. For the art historian David Peters Corbett, however, this work is entirely appropriate within the pages of Blast. Like the vorticist works therein, it is a ‘schematic image and summation which aims to encompass, from some intellectual point of vantage poised above the mêlée of contemporary life, its characteristic forms and meanings’.4

The picture was presented to Tate by an anonymous group of subscribers in 1920, of whom there is no record left among the Tate’s archives. However, it seems likely that they numbered Gore’s close friends. Following Gore’s death, Walter Sickert wrote to Nan Hudson:

We have got a committee (of which Clifton is hon. sec. & treasurer) including Ld. Hy. Bentinck, Swinton, Coloni, Holroyd, Campbell Dodgson, Brown, Steer, Tonks, Holmes, Marchant, Rutter, Gilman, me &c to buy a picture for a public gallery.5

Similarly, Harold Gilman wrote to Lucien Pissarro’s wife Esther:

We are raising funds to buy a picture for some public gallery – the proceeds to go to Gore’s wife. So many schemes have been started that I trust all will be well.6

Sickert reported in a letter to Ethel Sands: ‘We have already £180 for the purchase of a picture by Gore & the circulars only go out today!’7 It is likely that the donors of the Tate picture were the group Sickert listed, as no other work by Gore was presented to a public institution around this time. Why they delayed six years is difficult to explain, but may have been due to the uncertainties of the First World War. What is evident from the sum of £180 that Sickert mentions was that the amount spent on it was considerably higher than the prices Gore’s work usually fetched, and that this was, as Gilman indicated, partly a way of raising money for Gore’s family. As an unfinished painting it seems an unusual choice to represent Gore in a public collection. This might strengthen the idea that he was still working on it at his death, rather than having abandoned it.

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

1913, 20 x 16 in; Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1983 (42).

David Peters Corbett, ‘The Geography of Blast: Landscape, Modernity and English Painting, 1914–1930’, in David Peters Corbett, Ysanne Holt and Fiona Russell (eds.), The Geographies of Englishness: Landscape and the National Past, 1880–1940, New Haven and London 2002, pp.120–1.

Related biographies

Related essays

- City Visions: The Urban Scene in Camden Town Group and Ashcan School Painting David Peters Corbett

- The Camden Town Group and Early Twentieth-Century Ruralism Ysanne Holt

Related catalogue entries

Related archive items

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond 1913 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www