Stanislawa de Karlowska 1876–1952

Stanislawa de Karlowska in her artist's smock c.1897–8

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Fig.1

Stanislawa de Karlowska in her artist's smock c.1897–8

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

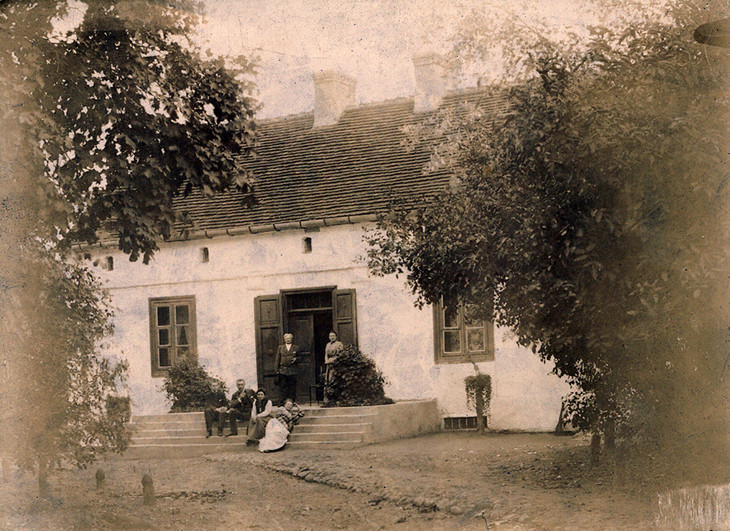

Stanislawa de Karlowska was born on 8 May 1876 at the family estate at Szeliwy, near the town of Lowicz in Russian-occupied Poland (fig.2).8 Her father, Alexander de Karlowski, was a Polish patriot who had fought in struggles for independence under the famous General Bem in 1848 and 1849, and taken part in the uprising of 1863, for which he reputedly ‘endangered his life and suffered considerable financial loss’.9 Karlowska’s son, Robert A. Bevan, said that her father and her brothers-in-law could best be described as ‘squirearchs’:

They had substantial estates, but they were not absentee landlords; they farmed the land themselves. They bred horses and cattle for themselves and for sale; they had their own water-mills, their own small forests and sawmills. They ate their own meat, poultry, and game, and fish from their own fish-ponds. Their sugar was made from their own sugar-beet. Bread was baked from their own wheat and rye. There was not very much flow of cash, but it was a life full of varied character: always something to see and do and talk about.10

The Karlowski family estate at Szeliwy, near Lowicz in Russian-occupied Poland c.1897/1899 from left to right: unknown man, Robert Bevan, Stanislawa de Karlowska, Stanislawa's father Aleksander Prawdzic-Karlowski, Stanislawa's sisters Halina and Julia

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Fig.2

The Karlowski family estate at Szeliwy, near Lowicz in Russian-occupied Poland c.1897/1899 from left to right: unknown man, Robert Bevan, Stanislawa de Karlowska, Stanislawa's father Aleksander Prawdzic-Karlowski, Stanislawa's sisters Halina and Julia

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Shortly after finishing at the Académie, Karlowska was invited to be the bridesmaid of her Polish friend and fellow student, Janina Flamm, who was marrying the British painter Eric Forbes Robertson (1865–1935). Robertson had been a close friend of Robert Bevan for over fifteen years. Karlowska and Bevan met at the wedding held in the Church of St Helier in Jersey on 17 July 1897, and their relationship developed quickly thereafter.

On his return to his family estate at Horsgate in Cuckfield, Sussex, Bevan began a series of twelve impassioned letters to Karlowska, who had returned home to Poland.13 Writing in their common language of French, in the first letter on 25 July, Bevan said that ‘la nuit après ton départ, j’ai pleuré, pleuré à chaudes larmes’ (the night after you left, I wept, wept hot tears), and invites her to call him ‘Bob’, calling her ‘Ma très, très chère Stasia’ (My very, very dear Stasia).14 On receiving a letter from Bevan in which he proposed to visit her in Poland that October, Karlowska wrote in phonetic French, ‘Je n’ai peu pas même t’ai dire quel joie tu me fais de venir si tôt’ (I cannot express how much joy you give to me by coming here so soon) and that ‘J’ai compte déjà les jours qui nous separt’ (I have already started counting the days we are apart). Further expressing her love, she wrote, ‘Tu sais quand je pense que bientôt nous serons ensemble, je suis tellement heureuse que je n’ai peu pas t’exprimer le sentiment que j’en ai’ (You know when I think that we will soon be together, I am so happy that I cannot express to you the feeling I have about it).15

Bevan decided he could not wait any longer to see Stasia again and, according to one report by their friend Marjorie Lilly, he took no heed of her instructions on how to enter Russian-occupied Poland:

She [Karlowska] told me that she was combing her hair when she heard the clatter of hoofs in the courtyard and looked through the window to see the rider and dropped the comb in surprise, saying, ‘Why, that’s my Englishman!’ This pursuit must have been most flattering; Bevan had travelled many versts across Poland to find her, but her father was not so impressed, he wanted to know more about this young Lochinvar before he gave his consent to the marriage.16

The two were married on 9 December 1897 in Warsaw, less than five months after their first meeting.17

The couple moved to England, although Karlowska was not familiar with the language. They initially lived at Horsgate with Bevan’s family and then at 3 Buxton Road in Brighton from 1898, where Bevan might have produced the lithograph of Karlowska, The Artist’s Wife 1898 (private collection).18 The couple finally settled at 14 Adamson Road in Swiss Cottage in 1900 where they lived for the rest of Bevan’s life (fig.3). Karlowska gave birth to their children at Horsgate: Edith Halina, called ‘Halszka’, on 28 December 1898 and Robert Alexander, called ‘Bobby’, in March 1901. Bevan painted Stasia and Halszka standing outside her Polish family home in The Gate at Szeliwy 1901 (private collection),19 and portraits of Karlowska in The Feathered Hat 1915 (private collection)20 and Stanislawa Bevan (née de Karlowska) 1920 (National Portrait Gallery, London).21

Stanislawa de Karlowska sitting in the drawing room at 14 Adamson Road, Swiss Cottage date unknown

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Fig.3

Stanislawa de Karlowska sitting in the drawing room at 14 Adamson Road, Swiss Cottage date unknown

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

That the work of the Women’s International Art Club, now being exhibited at the Grafton Galleries, is above the average is clear from the beginning. In the first room one meets with at least half a dozen women who have something uncommonly interesting to say in paint. Among them are three artists who are painting in colour, whose work is frank and honest, and not disposed of with a few fierce dashes of the brush, but in a complete, substantial, and emphatic way. What S. de Karlowska has to say she tells us lucidly in pure and harmonious colour. Her two studies of still life speak in the broadest, simplest, and most convincing terms.25

Karlowska also sent in five works, as did Bevan, to be exhibited at the first Allied Artists’ Association show in 1908. Her work was again singled out by Carter in a 1910 review of the AAA, writing that ‘Love and sincerity are apparent ... in the tender, subtle harmonies of S. de Karlowska’.26 It was through the AAA that Karlowska and Bevan first became acquainted with Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore, who invited Bevan to 19 Fitzroy Street after seeing his work. Although Karlowska was not a member of the Fitzroy Street or Camden Town Groups, she was friends with many of the members and inspired portraits by Gilman (figs.4 and 5) and Gore.27 She went on to exhibit with the London Group for many decades after her election in January 1914.

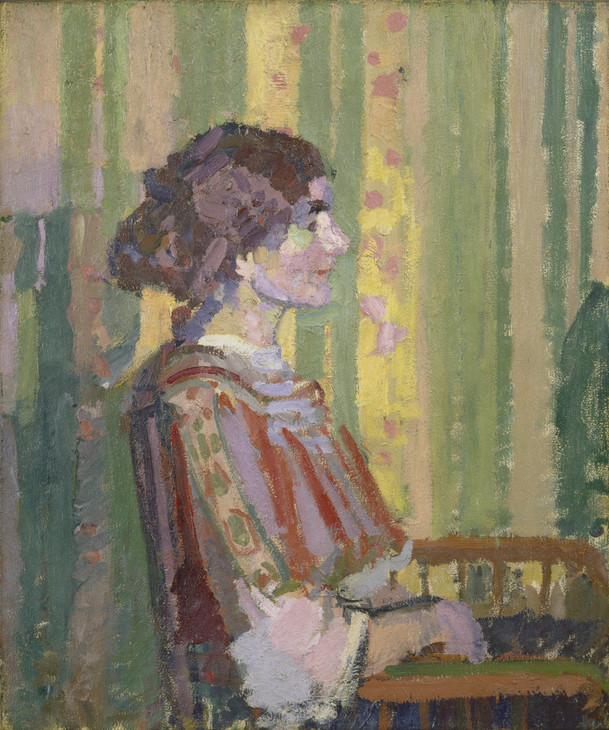

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Stanislawa de Karlowska (Mrs Robert Bevan) c.1913

Oil on canvas

618 x 514 mm

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund

Fig.4

Harold Gilman

Stanislawa de Karlowska (Mrs Robert Bevan) c.1913

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Stanislawa Bevan (née de Karlowska) c.1913

Oil on canvas

611 x 457 mm

National Portrait Gallery, London

Photo © National Portrait Gallery, London

Fig.5

Harold Gilman

Stanislawa Bevan (née de Karlowska) c.1913

National Portrait Gallery, London

Photo © National Portrait Gallery, London

Karlowska and Bevan had wide-ranging connections. Bobby later recalled that:

Both immediately before 1914 and later through the war, the Bevan house in Hampstead was a rallying-point not only for his [Bevan’s] closest associates but also for a number of other young artists. Tea-time on Sunday afternoons, often followed by a simple cold supper, usually saw quite a gathering which often included T.E. Hulme, Ashley Dukes, and the Gaudier-Brzeskas, as well as Sickert, Walter Bayes, Lucien Pissarro, Manson, and Wyndham Lewis.28

Karlowska and Bevan were particularly supportive of the impoverished French sculptor Henri Gaudier (1891–1915) and his partner who posed as his sister, the Polish writer Sophie Brzeska (1871–1925), who was of a similar age to Stasia. Karlowska bought several drawings and sculptures by Gaudier, and when he went to war in 1914 she sent him cigarettes and chocolates.29 In his final letter to her on 1 January 1915, Gaudier asked Karlowska, ‘Since I might fall, would you be so kind as to ask for my news from Capt. Ménager ... to send to my sister’.30 When he died later that year, Karlowska broke the news to Sophie.31

Karlowska’s work remained secondary to her husband’s, at her own choosing. Every year he spent months away painting in the countryside, while Karlowska often remained at home looking after the children and the house.32 Bobby recalled about his mother’s relationship with his father:

It was certainly a marriage for love, and she proved to be the best kind of wife he could have chosen. She had considerable beauty and charm, and, while she was far from being an intellectual, she had a natural and endearing vivacity which helped to counteract my father’s dislike of asserting himself in unfamiliar company. Her unquestioning confidence in him and her outspoken pride in his work were not shaken for the rest of his life by his uncommunicativeness and long withdrawals into himself. I once asked him, when I found he had destroyed a picture I had greatly admired, whether he was ever completely discouraged by his lack of success with critics and collectors. He answered to this effect: ‘Your mother, of course, thinks I am a great artist. I don’t know about that, but I am sure that I could not go on without believing that I had done some good work and was capable of better. She, too, has always complained of the amount of work I destroy; but it is easy to exercise that kind of self-criticism when work is left unsold on your hands. That she has always shown such confidence has always meant a very great deal to me.’33

On occasions Karlowska did travel out to meet her husband in the countryside (fig.6), where she painted works including At Church Staunton, Somerset c.1916 (University of Hull) and Luppitt Post Office c.1920 (private collection).34

Stanislawa de Karlowska smoking in the doorway of Lytchetts in Devon c.1917–18

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Fig.6

Stanislawa de Karlowska smoking in the doorway of Lytchetts in Devon c.1917–18

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

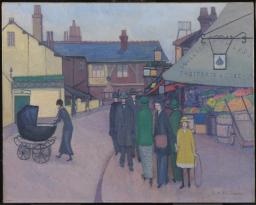

Karlowska held her first solo exhibition at the Adams Gallery in October–November 1935, selling six paintings.37 The preface for the catalogue was written by a former Camden Town Group member and then director of the Tate Gallery, James Bolivar Manson. He wrote that Karlowska ‘really needs no introduction to the discriminating part of the London public that cares about the art of painting’.38 Her work he found simple, sincere and individual, saying that ‘It is modern in feeling but it owes nothing to any school’.39 About her subject matter, he wrote, ‘She finds beauty in the most ordinary scenes: street corners, the backs of houses and so on and with such “motifs” she produces satisfying works of art.’40 The critic of the Times also appreciated the exhibition:

In her 39 paintings at the Adams Gallery, 2, Pall Mall Place, Miss S. de Karlowska, who is the widow of Mr. R.P. Bevan, excites interest and wins approval by the quiet consideration of her methods and her nice discrimination in effects of colour. Probably her best picture is ‘St. James’s Square,’ in which acceptance of symmetry in the composition, with gate, statue, and tall house in a central vertical series, has produced a novel effect. ‘Berkeley Square,’ apart from its gravity, pleases by the justness with which a moment of twilight has been recorded, and there is a happy appreciation of oddity in ‘A Little Church in Cracow.’ Probably, having mastered her convention, the artist would gain by working a little closer to the facts, and ‘Woodnesborough’ strikes one as the best of the landscapes. ‘Portman Square,’ again, suggests that toned colour rather than pure colour is her natural field of enjoyment.41

Following the exhibition, Berkeley Square was presented to the Tate Gallery (N04816).

Karlowska remained friends with Camden Town and Cumberland Market Group colleagues, including Malcolm Drummond, John Nash, Walter Sickert and particularly Charles Ginner.42 In 1936 she moved to a flat at 46 Russell Square, Bloomsbury, where her son was living at number 41, and the two hosted ‘At Homes’ to which artistic friends were invited.43 In 1939 Karlowska moved to nearby Torrington Square, but when war broke out she moved to Chester to live with her daughter at 15 Abbey Street. There she painted the wartime scene, Barrage Balloons 1939 (Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne).44

After the war she returned to London, living at 9 Collingham Road, Earls Court, still retaining her independence rather than agreeing to lodge at her son’s home, Boxted House in Essex.45 But by 1952 she had moved to a nursing home in Cadogan Place,46 and died on 9 December that year at the age of seventy-six, ‘a victim of the frightful fog’.47 She was buried in the Bevan family grave at Cuckfield. The painter, art teacher and friend of the Camden Town Group, Hubert Wellington, wrote to Bobby:

I was grieved to read of your Mother’s death in the Times yesterday. ... She was a great dear as well as being a very genuine & sensitive artist: Charlotte and I were both very fond of her. Indeed she was one of the few people of whom I have never heard unkindly or nasty things said.48

Karlowska had been such an integral part of the London Group that when she had previously sent in no work for two exhibitions, the secretary Eleanor Porter wrote to her in 1951:

This is the second London Group exhibition to which you have sent no pictures, and I, and many others judging from the enquiries which have been made, are wondering if you are abroad, if you have lost interest in the Group or if you are by any chance ill. As your address is at last in the catalogue it is possible to write to you and tell you that so many friends would like to see you and have news of you.49

Following her death, as part of the London Group show in 1953, a memorial display of four works was exhibited. Bobby wrote in the catalogue:

Among her happiest memories was the communal artistic life that centred round Fitzroy Street and the Camden Town and Cumberland Market Groups. She loved people and travel, bought pictures whenever she had a little money to spare, and enjoyed pressing hospitality on her friends. Exiled from London during the war, she eagerly tried to take up her old life again on her return, though many old friends had died and she had lost touch with others. She continued to paint and exhibit for some years, and even when increasing feebleness made this impossible, she kept a lively interest in the new painting shown in London. And she continued brave and gay till her peaceful death on 9th December, 1952.50

A memorial exhibition was organised by Bobby at the Adams Gallery in October 1954, following which the two other works in the Tate collection were presented: Fried Fish Shop c.1907 (N06238) and Swiss Cottage exhibited 1914 (N06239). The Anglo-Polish Society held an exhibition of Karlowska’s and Bevan’s work in March–April 1968 when their daughter Halszka was chair of the society,51 in appreciation of the couple’s support of Polish people.52 An exhibition of paintings was also held at the Maltzahn Gallery in June 1969.53

Notes

Voting list for meeting of the London Group, 3 January 1914, Tate Archive TGA 806/10/6. See also Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.66.

See, for example, Adamson Road, NW3 c.1918 (Manchester City Art Gallery), At Chalk Farm c.1922 (private collection), Russell Square from Montague Street 1931–5 (Museum of London), New Church, Regent Square c.1935 (private collection) and Back Gardens before 1936 (private collection). Russell Square from Montague Street is reproduced at http://www.20thcenturylondon.org.uk . Adamson Road, NW3 is reproduced in An Exhibition of Selected Paintings by Robert Bevan, 1865–1925, and his wife Stanislawa de Karlowska, 1876–1952, Anglo-Polish Society, London 1968. Other works are reproduced at http://www.bridgemanart.com .

See, for example, Lock on the Canal 1913 (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge), Industrial Roofscape c.1931 (private collection) and Corner of Russell Square c.1935 (private collection). Reproduced at http://www.bridgemanart.com .

See, for example, Woodlands before 1915 (private collection), Dumpdon Hill c.1920 (private collection), Landscape before 1936 (private collection) and At the Edge of the Village before 1936 (private collection). Reproduced at http://www.bridgemanart.com .

See, for example, Polish Interior 1909 (Southampton City Art Gallery) and Church of the Holy Spirit, Cracow 1926 (Wakefield Museums and Galleries). Polish Interior is reproduced in Gill Hedley, Let her Paint: Ten Women Painters in Southampton City Art Gallery, Southampton City Art Gallery 1988, p.13. Church of the Holy Spirit, Cracow is reproduced at http://www.bridgemanart.com .

Grant M. Waters, Dictionary of British Artists Working 1900–1950, Eastbourne 1975, p.186. The artist’s great-grandchild, Patrick Baty, notes that the correct Polish spelling of her name includes barred ‘l’s. In England her name has been written without them (letter to the author, 11 November 2010).

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, London 1964, vol.1.

Robert Bevan, letters to Stanislawa de Karlowska, 25 July–24 September 1897, Tate Archive TGA 9210/1/1.

Robert Bevan, letter to Stanislawa de Karlowska, Horsgate, Cuckfield, Sussex, 25 July 1897, Tate Archive TGA 9210/1/1.

Stanislawa de Karlowska, letter to Robert Bevan, Szeliwy, 23 August 1897, Tate Archive TGA 9210/1/3.

Visiting Poland went on to have a substantial impact on Bevan’s art. He painted numerous works there over his lifetime, such as Polish Landscape c.1901 (Leicester Museum and Art Gallery), Bringing the Calves Home, Poland 1901–2, two versions of The Smithy at Szeliwy c.1903 and c.1906–7 (private collections) and A Polish Church, Mydlow 1921–2 (private collection). A Polish Church, Mydlow is reproduced in From Sickert to Gertler: Modern British Art from Boxted House, exhibition catalogue, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh 2008 (16), and the others in Bevan 1965, pls.15, 14, 18, 19.

Reproduced in Frances Stenlake, Robert Bevan: From Gauguin to Camden Town, London 2008, p.153. The squared-up drawing for the painting, in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London is also reproduced.

NPG 5202. Reproduced at the National Portrait Gallery, London, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait.php?search=sp&OConly=true&sText=karlowska&rNo=1 , accessed 6 January 2011.

A Gore portrait is reproduced in The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988 (6). Another Gilman portrait, The Yellow Hat c.1913, is reproduced in Stenlake 2008, p.153, and another, Mrs Robert Bevan c.1911, is reproduced in English Paintings from the Bevan Collection: A Memorial Exhibition for R.A. Bevan 1901–1974, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1975 (12).

See Alice Strang, ‘Bobby and Natalie Bevan and the Art at Boxted House’, in National Galleries of Scotland 2008, p.14.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, letter to Mrs Stanislawa Bevan, 1 January 1915, private collection. Quoted in Strang 2008, p.14.

Frances Stenlake, From Cuckfield to Camden Town: The Story of Artist Robert Bevan (1865–1925), Cuckfield, Sussex 1999, p.48. Gaudier discussed Karlowska’s work in a review of the AAA, saying that she ‘has a good picture – a happy composition of figures in a half-circle – figures of secondary importance to the composition – and a great relief with it, the absence of pink atmosphere’. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, ‘Allied Artists’ Association Ltd.’, Egoist, 16 March 1914.

James Bolivar Manson, ‘Preface’, in Paintings by S. de Karlowska, exhibition catalogue, Adams Gallery, London 1935. Copy in the collection of the Tate Archive TGA 9216/109.

Letters from all four are in the Tate Archive, TGA 9216. Ginner’s are the most numerous, see TGA 9216/40–50.

Robert A. Bevan, ‘S. de Karlowska (Mrs. Robert Bevan)’, in London Group: Annual Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, New Burlington Galleries, London 1953, p.4.

Frances Stenlake, ‘Bevan is Good for You: Bobby’s Promotion of his Father’s Work’, in National Galleries of Scotland 2008, p.28.

An Exhibition of Selected Paintings by Robert Bevan, 1865–1925, and his Wife Stanislawa de Karlowska, 1876–1952, Anglo-Polish Society, London 1968.

Catalogue entries

How to cite

Helena Bonett, ‘Stanislawa de Karlowska 1876–1952’, artist biography, January 2011, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www