Walter Bayes Under the Candles: Mr Charles Ginner Presiding 1933

Walter Bayes,

Under the Candles: Mr Charles Ginner Presiding

1933

© Tate

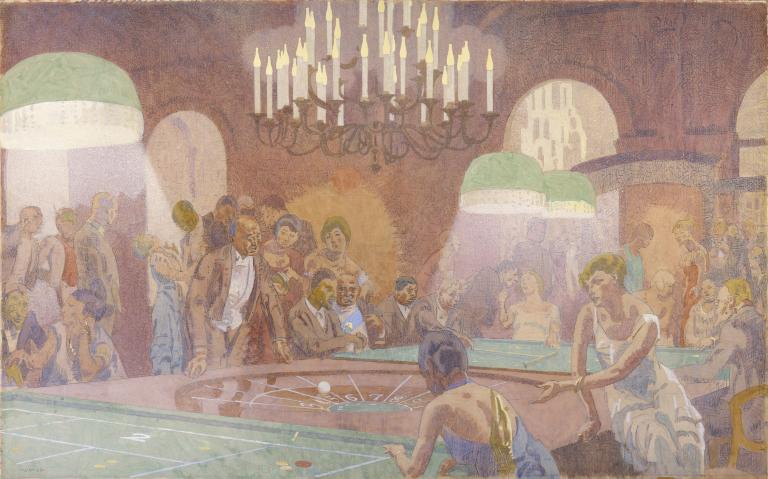

Bayes’s study reveals the subterranean interior of a casino, under green-shaded electric lights and a massive chandelier. Surrounded by artfully posed and richly dressed clientele, the old man at the Boule table is identified as the artist Charles Ginner. This is a rare outing for Ginner, however, as he was then reputed to be reticent, shy and frugal.

Walter Bayes 1869–1956

Under the Candles: Mr Charles Ginner Presiding

1933

Gouache and graphite on tracing paper

724 x 1168 mm

Inscribed by the artist in black ink ‘·WB·33·’ bottom left

Presented by the friends associated with the artist during his Headmastership of the Westminster School of Art 1934

N04738

1933

Gouache and graphite on tracing paper

724 x 1168 mm

Inscribed by the artist in black ink ‘·WB·33·’ bottom left

Presented by the friends associated with the artist during his Headmastership of the Westminster School of Art 1934

N04738

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist by the committee of the Walter Bayes testimonial, Westminster School of Art, May 1934 and presented to Tate Gallery.

Exhibition history

1934

Exhibited to the subscribers to the Walter Bayes testimonial fund, Westminster School of Art, June 1934 (no catalogue).

References

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, p.33.

Technique and condition

Under the Candles: Mr Charles Ginner Presiding is executed on tracing paper, which has been laid on board. The paint carries over on to the board indicating that the tracing paper was probably fixed to it before painting commenced. A raking light shows that the paper is quite rippled with air bubbles in places. There are pin holes all over the paper, which might indicate a number of things. It could be that a hole was made to get rid of an air bubble and thus flatten the paper. Alternatively, where the pin holes follow an outline, such as the face of the blonde female figure in the foreground on the right, they could have been made to mark the outline on to the canvas, for which this is the study. Or the holes could denote that a carbon paper was put over the top to draw from.

Faint lines are still visible where the paper has been squared up in quite large squares, but most of these have been erased. The pencil lines have been drawn in one go with no erasing. White gouache has been splattered in areas, which evokes the haze of cigarette smoke.

Piers Townshend and Helena Bonett

June 2010

How to cite

Piers Townshend and Helena Bonett, 'Technique and Condition', June 2010, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Under the Candles: Mr Charles Ginner Presiding 1933 by Walter Bayes’, catalogue entry, September 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

In a letter to the Tate Gallery written in 1954, Walter Bayes explained that Under the Candles: Mr Charles Ginner Presiding was a study for an oil painting exhibited at the Royal Academy.1 He added that his painting had been ‘dreadfully skied’ during display, meaning that it had been hung so high that it was virtually impossible to see it. Since the study is dated 1933 and Bayes did not exhibit at the Academy between 1931 and 1935, Mary Chamot, an Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery, reasoned that the picture must have been the work entitled La Vie Galante – ‘On Sonne’ (The Gentlemanly Life – ‘Someone Rings the Bell’),2 exhibited at the Summer Exhibition of the Royal Academy in 1936.3 The appearance and whereabouts of this painting are currently unknown but the title does not seem to bear much relation to the appearance and subject of Under the Candles. However, as the art historian Wendy Baron has pointed out, Bayes did have a tendency to give his works obscure titles with cryptic meanings.4 It is possible that the French title has a colloquial meaning which has been lost owing to translation or the passage of time.

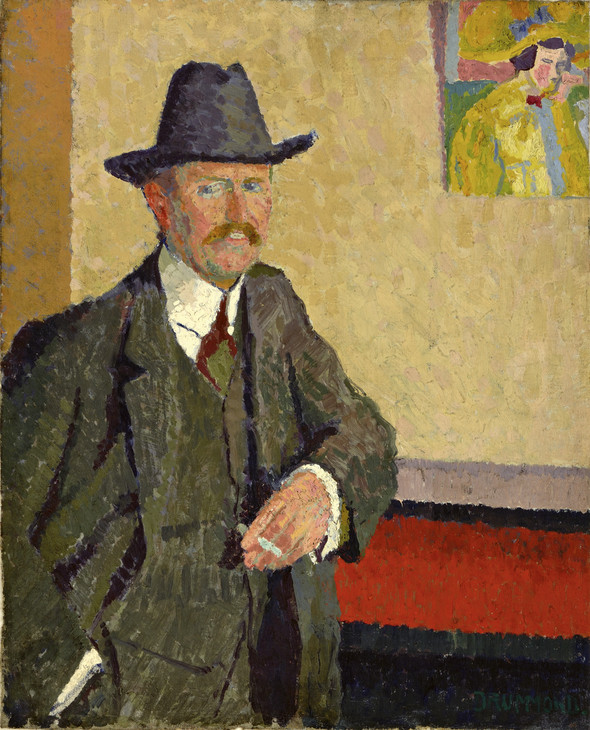

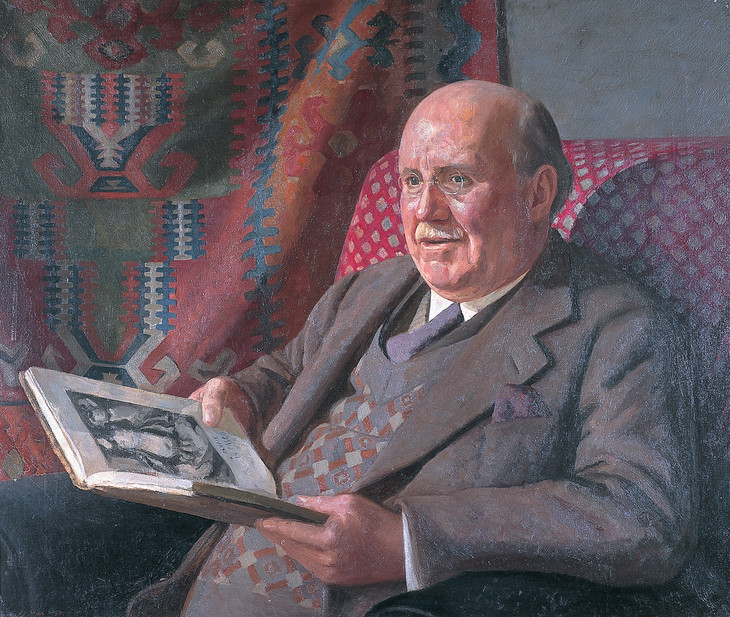

Under the Candles: Mr Charles Ginner Presiding depicts the crowded interior of a room in a casino, structured by arches and columns and lit by low, green-fringed lampshades and a large electric chandelier. The harsh lighting cast by these light sources creates bright highlights on the sheen of fabric and jewellery which Bayes has depicted with acidic colours and bold touches of gouache, painted over an underdrawing of crosshatched pencil lines, characteristic of his drawing technique. The foreground is dominated by one long gaming table around which are grouped a number of men and women participating in the gambling. The artist Charles Ginner is probably the man standing on the left of the table, leaning forward with both hands placed beside the wheel. As a young man, Ginner’s character and looks were reportedly rather dashingly French, and this is how he appears in a portrait by Malcolm Drummond of 1911 (fig.1). In 1933, however, he would have been fifty-five and his appearance was rather altered. His friend Marjorie Lilly recorded that he was a ‘thick-set, sturdy, short-necked man with a round, bald head and a bun-shaped face’,5 a description which is confirmed by other contemporary depictions of Ginner such as Portrait of Charles Ginner 1930 (fig.2) by Edward Le Bas. No other portraits have been identified within the work.

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

Charles Ginner 1911

Oil paint on canvas

603 x 490 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.1

Malcolm Drummond

Charles Ginner 1911

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Edward Le Bas 1904–1966

Portrait of Charles Ginner 1930

Oil on canvas

Private collection

© Estate of Edward Le Bas

Photo © Janet Balmforth

Fig.2

Edward Le Bas

Portrait of Charles Ginner 1930

Private collection

© Estate of Edward Le Bas

Photo © Janet Balmforth

Ginner’s appearance in this casino painting is mysterious and raises a number of unanswered questions. Bayes and Ginner were obviously well acquainted through their membership of the Camden Town and London Groups and, in 1920, Bayes wrote a catalogue introduction for an exhibition of work by Ginner, John Nash and Frank Dobson.6 The inclusion of Ginner’s portrait amidst a gambling scene, however, is surprising and does not tally with the scant biographical information known about his personal life at this time. Ginner is generally remembered as a reserved character who, according to his friend, Benjamin Fairfax Hall, was reticent and shy and lived a ‘simple life’.7 He never made much money from his paintings during his lifetime and, although Walter Sickert suspected that he received a private allowance from his father,8 Marjorie Lilly recorded that he was ‘very poor ... but persisted in an extravagant use of oil paint’.9 The former Director of the Tate Gallery, John Rothenstein, who visited Ginner in later years at his Pimlico home, portrayed him as quiet, modest and somewhat reclusive.10 Fairfax Hall, however, recorded that Ginner not only kept a mistress, but also paid for the education and welfare of two daughters belonging to a woman whom he had loved as a young man but who had chosen to marry somebody else.11 Wendy Baron has suggested that this old flame was a Danish artist and Fitzroy Street inhabitant, Dora Sly, née Erichsen (died 1943).12 Their unusual financial arrangement was visualised by Sickert in an etching, entitled A Little Cheque 1912–13.13 The image depicts Mrs Sly reclining on a sofa whilst in the background a portly male figure, identified by name as Ginner on one of Sickert’s touched proofs, sits at a desk writing out a cheque.14 Given, therefore, his evident limited financial means, the various drains on his resources and his reportedly reserved character it is unlikely that Ginner had the surplus funds or the desire for frequent gambling forays at the casino and it is not known why he appears as the named protagonist in Bayes’s painting, ‘presiding’ over the games. Both Bayes and Ginner took regular painting ‘holidays’, so the scene possibly records the occasion of a sociable evening’s entertainment during a sketching trip taken together, with Ginner prepared and suitably attired in white tie and tails. However, it is also possible that Bayes included his portrait as a sort of ‘cameo’ appearance, to fulfil some private joke or tacit reference to his former colleague.

Subject and location

Ginner appears absorbed in the outcome of the game in front of him whilst all around the table other people finger their tokens and look on as a croupier rakes in the chips just lost in the round. The game being played features a large numbered wheel and a white ball set in between two green baize tables marked with a numbered layout which is not, as might first be thought, roulette, but a French derivation known as ‘boule’. Unlike the wheel in roulette, which is numbered irregularly from 0–36, the boule wheel consists of eighteen pockets numbered consecutively from 1–9 twice.15 Bets are placed by putting chips down upon the table layout, either on a single number, or a group of numbers. The winning number is decided by rolling a rubber ball, larger than that used in roulette, around the boule dish until it comes to rest in one of the numbered pockets.16 Boule was developed in Europe during the early eighteenth century and although relatively unknown in Britain, it remains a popular feature in casinos across France and Spain to the present day. In Switzerland, where casino gambling was outlawed between 1929 and 1993, boule was the only game licensed to continue in special gaming houses.17 The advantage to the house bank is higher than that in roulette and the stakes are traditionally lower, and therefore boule is sometimes called ‘the poor man’s roulette’.18 In Bayes’s picture, the ball is resting in the number 5 pocket which may explain the look of dismay upon Ginner’s face. The number 5 acts like the zero in roulette, invalidating all other money bets.

The location of Under the Candles has not been recorded but the fact that the figures in the drawing are playing boule suggests that this is a French casino, possibly at Boulogne. Bayes, who frequently visited France on summer painting trips, painted a number of views during the 1920s and 1930s of the coastal town of Boulogne-sur-Mer, including a number of views of the town’s casino. The catalogue for Bayes’s solo exhibition at the Goupil Gallery in 1928 lists three examples, Bolougne Casino, Entrance to Bolougne Casino and Verandah of Bolougne Casino (whereabouts of all unknown).19 Although initially the preserve of rich aristocrats in Europe’s exclusive spa resorts during the nineteenth century, casinos became an established feature of the tourist industry after France legalised gambling in 1907.20 They were particularly to be found in fashionable seaside towns such as Cannes and Biarritz, and the Channel ports popular with English visitors such as Dieppe. French casinos not only offered tourists the opportunity to risk their money at the gaming tables but were centres for a whole host of diversions and entertainments. The casino complex at Bolougne-sur-Mer included a restaurant and an elegant terrace with formal gardens, depicted by Bayes in his painting Bolougne Casino, Promenade 1935 (private collection).21

Bayes completed a number of other paintings with casinos as their subject. In 1925 he exhibited a painting at the Royal Academy called Les Jeux sont faits (The Chips are down) (whereabouts unknown).22 A review in the Times in 1929 reveals that this painting was similar in detail, colour and appearance to Under the Candles:

His most elaborate composition here is a large painting of a casino interior, Les Jeux sont faits. A chandelier of many lights and the roulette board in perspective establish the general plan of the design, and the architecture – broken by the downpour of light from green shades – is composed upon it with extraordinary skill, four principal figures marking out the main dimensions. The balance of colour, green and reddish mauve pre-dominating, is all that could be desired. All this sounds coldly scientific, but the emotional and physical atmospheres of the subject are sufficiently conveyed, and the painting would be an ideal decoration for some place of recreation or refreshment on ‘modern lines’.23

This description suggests that Les Jeux sont faits might be the exhibited painting for which the Tate’s work is the study. The inscribed date of ‘33’ in the bottom left-hand corner of Under the Candles may perhaps have been added a decade later as a result of some revisions or additional touches prior to the purchase of the painting by the Tate Gallery.

Bayes was perhaps introduced to the casino as a suitable subject for painting by his friend and colleague Walter Sickert, who painted scenes of the casino at Dieppe in 1920–1. Unlike Sickert’s paintings of music halls which reveal the leisure time of the working-class urban population, his casino paintings focus on the fashionable and rich, resplendent in their furs and evening dress (see Tate N05089). All casinos during this period had a strict dress code and the people portrayed in Bayes’s painting are also suitably glamorously attired, with the men in dinner jackets or tails, and the women in long evening gowns. As in Sickert’s paintings, the casino is portrayed as rather a strange, subterranean place where the stilted gestures of interaction between the gamblers are as artificial as the electric candles illuminating the proceedings.

The Westminster School of Art

Sickert once described Bayes’s development as an artist as ‘slow, very slow’.24 The same could not be said however of his career as an art critic and teacher which was extremely successful. Under the Candles: Mr Charles Ginner Presiding was presented to the Tate Gallery by a committee of subscribers formed to commemorate the occasion of Bayes’s retirement as Headmaster of the Westminster School of Art, a position he had held between 1918 and 1934. His friends and colleagues decided to purchase one of his works for presentation to the National Collection and the subject was broached to the Director of the Tate and Bayes’s former Camden Town Group colleague, James Bolivar Manson. Frank Medworth (1892–1947), a former pupil and then a teacher at the school, wrote to Manson on behalf of the committee, ‘Mr Walter Bayes R.W.S., has been directing the Westminster School of Art for fifteen years ... We feel that he is outstanding from amongst his contemporaries, and, if it should be possible for you to assist us in this, we think that it would be a fitting testimonial for us to present a work of his to the public.’25 Manson approved the idea and Under the Candles: Mr Charles Ginner Presiding was chosen as a work considered both ‘suitable and representative’. It was duly purchased with funds subscribed by staff and students and shortly after entering the collection of the Tate, it was borrowed back for display at a ceremonial presentation to Bayes on 8 June 1934.

The Westminster School of Art played an important role in the history of the Camden Town Group. Bayes himself compared it to London’s other major art schools as ‘by far the smallest, the least official, the least endowed’,26 yet its list of alumni and staff indicates that it was more than capable of holding its own as one of the most influential centres for the training of modern artists at the beginning of the twentieth century. Its teaching methods were certainly more independent and forward thinking than the conservative regimes upheld at the established institutions such as the Royal Academy and the Royal College of Art. It had been founded as a government school of art in 1876 and was initially based at the Royal Architectural Museum in Tufton Street. In 1903 it was taken over by the London County Council and was incorporated into the premises and management of the L.C.C. Westminster Technical Institute at Vincent Square, off Rochester Row, where it remained until its closure sometime during the Second World War. The Institute was geared towards providing education and training courses for practical and technical vocations such as civil and gas engineering, building surveying, construction and catering. The School of Art existed as a separate unit within the Institute’s premises and concentrated primarily on instruction in drawing and painting. To some extent it shared the objectives of the Institute which encouraged education with a view to employment, and classes were offered for students who wished to turn their artistic abilities to a professional craft such as book-binding or commercial design. There was also some cross-over of classes for architectural and construction students learning drawing skills.

Like the Slade School of Art, the Westminster School of Art played a significant role in training, shaping and bringing together the generation of artists who were to become London’s artistic avant-garde at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Westminster, however, was quite a different sort of place to study than the autonomous and self-consciously ‘arty’ Slade. Alfred Thornton (1863–1939), who attended both schools, recalled that the atmosphere between the two was very different.27 At the Slade, the tutors were working studio artists first, and teachers second.28 The majority of Slade entrants were middle- and upper-class students and there was a particularly high intake of women.29 By contrast, many pupils attended the Westminster part-time or in the evenings through a necessity to earn a living at the same time, and it was, therefore, much more of a ‘working man’s’ art school. Henry Tonks (1862–1937), Bayes’s opposite number at the Slade from 1918–30, began his own artistic career at the Westminster, taking evening classes under Frederick Brown (1851–1941) whilst he worked as a surgeon during the day. He described the Westminster as a ‘truly comic and dirty little studio’ which ‘became the centre of revolution which has done much to destroy the powerful vested interests of those days’.30 The ethos of the School was one of commitment and hard work, without the drama and penchant for eccentric behaviour which seemed to proliferate amongst certain Slade students. It was a friendly place where, according to artist Stella Bowen (1895–1947) who moved there from the Slade, ‘they didn’t believe in grief and tears [and] never had any suicides amongst the students’.31

Given the down-to-earth and somewhat humble but progressive nature of the Westminster School of Art it is perhaps not surprising that a high proportion of members of the Camden Town Group were affiliated with it at some point in their careers. Robert Bevan, Duncan Grant, Malcolm Drummond and Bayes all attended classes as students, whilst Drummond, Bayes, Spencer Gore and Harold Gilman also taught there. The most famous associate was undoubtedly Sickert who taught there in 1908–12 and 1915–18. Sickert’s passion for painting was matched only by his enthusiasm for teaching. He wrote to Ethel Sands from the Institute:

Here we are, here we are, here we are again! I know. The stairs are the worst part. The teaching itself is interesting & teaches me ... I am under a charming & most sympathetic head-master [W.M. Loudan (1868–1925)] & my staff that acts as if I were Solon [an Ancient Greek wise man and lawgiver] which embarrasses me, & makes it difficult to [suppress] a fit of the giggles ... I can’t conceive heaven without

1. painting in a sunny room an iron bedstead in the morning

2. painting in a north light studio from drawings till tea-time

3. giving a few lessons to eager students of both sexes at night.32

1. painting in a sunny room an iron bedstead in the morning

2. painting in a north light studio from drawings till tea-time

3. giving a few lessons to eager students of both sexes at night.32

The emphasis on practicality at the Institute was something of which Sickert greatly approved. In an article in the English Review in 1912, he expressed the opinion that art education should not be the preserve of those who can afford it, nor should it be wasted on students without any real talent or application. He wrote:

There will probably soon be a considerable revision of opinion among municipalities as to the utility of spending the money of the ratepayers on indiscriminate art teaching at all. It has often struck me as an anomaly that the poorest tram conductor, and the poorest charwoman are taxed through their rents, and otherwise, in order to pay the salary of the likes of me for teaching classes, largely consisting of well-to-do ladies and gentlemen to paint pictures that no one wants. The Institutes are tending, I think wisely, to bestow more and more attention on useful things like plumbing and building, cooking and waiting, and, even in the domain of the arts, on such branches as can be applied to industries already commercially in being.33

It was Sickert who recommended Bayes for the position of headmaster at the Westminster in 1918.

During his time as headmaster, Bayes instituted a number of changes in the focus and type of teaching which continued to maintain the reputation of the School as a centre for the development of modern art. The prospectus for the academic year 1921–2, early in Bayes’s headmastership, reveals that the teaching was conducted along fairly traditional lines on the model of the Royal Academy Schools.34 All students were expected to attend drawing classes from antique sculptures and only when they were judged sufficiently competent could they graduate to the life class. Furthermore, an Inspector’s report from 1919 had already criticised the ‘tendency to overlook the fact of the individuality of the students and to lead them too much in the same restricted groove’.35 By contrast, twelve years later, just prior to Bayes’s retirement, the prospectus highlights the ‘considerable influence’ of the School on the development of modern art.36 The staff list included artists as varied as Bernard Meninsky (1891–1950), Adrian Allinson (1890–1959) and Mark Gertler (1892–1939), ‘whose work is widely different in character, but is based on the same fundamental principles’ and the hope is expressed ‘that the school will exert a valuable influence on the next phase of artistic development, by assisting in the process of consolidation, and by checking the tendency to uncritical reaction inevitable after a period of many experiments’.37 Sickert approved of the principles upheld at his former place of employment, describing Bayes and his staff as ‘half the flower of the modern movement’.38

Nicola Moorby

September 2003

Notes

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, p.33.

The One Hundred and Sixty-Eighth Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1936 (736).

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.146.

B. Fairfax Hall, Paintings and Drawings by Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner in the Collection of Edward Le Bas, London 1965, p.29.

Exhibition of Oil Paintings by Walter Bayes, exhibition catalogue, Goupil Gallery, London 1928 (13, 27 and 42).

Jan McMillen (ed.), Gambling Cultures: Studies in History and Interpretation, London and New York 1996, pp.264–6.

The One Hundred and Fifty-Seventh Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts, London, May–August 1925 (296).

Walter Sickert, ‘Preface’, in Exhibition of Paintings by Walter Bayes, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1918.

Pupil and Master: Reginald Goodfellow (1894–1985) and Walter Bayes (1869–1956), exhibition catalogue, Parkin Gallery, London 1986, [p.4].

Walter Sickert, ‘Mural Decoration’, English Review, July 1912, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.326.

Related biographies

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Under the Candles: Mr Charles Ginner Presiding 1933 by Walter Bayes’, catalogue entry, September 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www