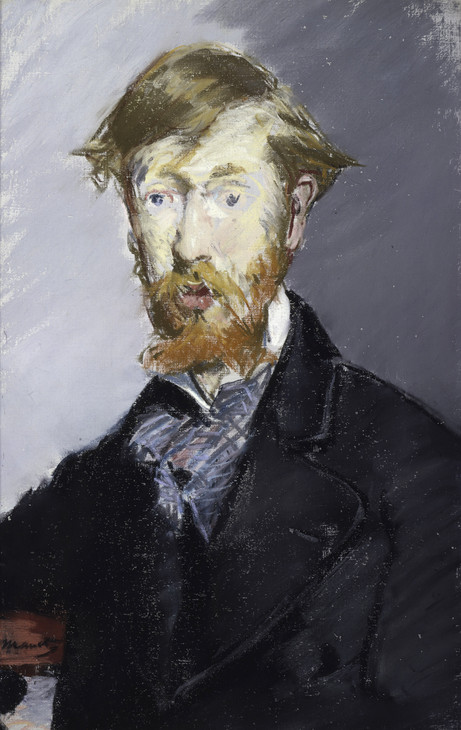

Walter Richard Sickert George Moore 1890-1

Walter Richard Sickert,

George Moore

1890-1

George Moore, the Irish painter turned novelist and critic, first met Walter Sickert in Dieppe. The two men shared sympathies with French impressionism as well as the literature of Zola and Balzac. First exhibited at the New English Art Club in 1891, Sickert’s impressionist treatment of Moore’s colourful character was commended as well as being derided as a ‘boiled ghost’.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

George Moore

1890–1

Oil paint on canvas

603 x 502 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ bottom left and ‘George Moore’ on stretcher on back

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1917

N03181

1890–1

Oil paint on canvas

603 x 502 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ bottom left and ‘George Moore’ on stretcher on back

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1917

N03181

Ownership history

Acquired from the artist by Philip Wilson Steer (1960–1942), by whom given to the Contemporary Art Society c.1911; presented to Tate Gallery 1917.

Exhibition history

1891

New English Art Club, London, Winter 1891 (48, as ‘Mr George Moore’).

1893

?New English Art Club, Newcastle, 1893 (50, as ‘Portrait of Mr George Moore’).

1911

Loan Exhibition of Modern Pictures, Drawings, Bronzes, Etchings and Lithographs, Municipal Art Gallery, Kingston upon Thames, July–September 1911 (29, as ‘Portrait of George Moore’).

1911–12

Loan Exhibition of Works Organised by the Contemporary Art Society, Manchester City Art Gallery, December 1911–January 1912 (83, as ‘Portrait of George Moore’).

1912

Loan Collection of Modern Paintings Organised by the Contemporary Art Society, Laing Art Gallery and Museum, Newcastle upon Tyne, October 1912 (186, as ‘Portrait of George Moore’).

1913

The Contemporary Art Society: First Public Exhibition in London of the Works Acquired by the Society by Gift and Purchase, Augmented by Loans from Various Sources, Goupil Gallery, London, April 1913 (22).

1923

Contemporary Art Society Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings, Grosvenor House, London, June–July 1923 (6, as ‘Portrait of George Moore, Esq.’).

1927

?Liverpool, August–December 1927 (recorded in the Tate Gallery Loans Out ledger 1899–1932).

1946–7

Modern British Pictures from the Tate Gallery, (British Council tour), Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, January–February 1946 (84), Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, March 1946 (84), Raadhushallen, Copenhagen, April–May 1946 (84), Musée du Jeu de Paume, Paris, June–July 1946 (84), Musée des beaux-arts, Berne, August 1946 (87), Akademie der Bildenden Kunste, Vienna, September 1946 (88), Narodni Galerie, Prague, October–November 1946 (88), Muzeum Narodwe, Warsaw, November–December 1946 (88), Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Rome, January–February 1947 (88), Tate Gallery, London, May–September 1947 (3181).

1947–8

Modern British Pictures from the Tate Gallery, (Arts Council tour), Leicester Museum and Art Gallery, September–October 1947, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, October–November 1947, Birmingham City Museum and Art Gallery, November–December 1947, Bristol City Art Gallery, January–February 1948, Russell-Cotes Art Gallery, Bournemouth, February–March 1948, Brighton Art Gallery and Museum, March–April 1948, Plymouth Art Gallery, April–May 1948, Castle Museum, Nottingham, May–June 1948, Huddersfield Museum and Art Gallery, June–July 1948, Aberdeen Art Gallery, July–August 1948, Salford Art Gallery and Museum, August–September 1948 (56).

1960

Contemporary Art Society 50th Anniversary Exhibition, Tate Gallery, London, April–May 1960 (67).

1967

Decade 1890–1900, (Arts Council tour), Camden Arts Centre, London, January–February 1967, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, February 1967, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea, March 1967, City Art Gallery Birmingham, April 1967, Art Gallery Bolton, April–May 1967, City Art Gallery, Bradford, May–June 1967, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, June–July 1967, Reading Art Gallery, July–August 1967 (31).

1968

Fifth Adelaide Festival of Arts: Walter Sickert, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide 1968 (7).

1977–8

Sickert, (Arts Council tour), Ferens Art Gallery, Hull, December 1977–January 1978, Glasgow Art Gallery, February–March 1978, City Museum and Art Gallery, Plymouth, April–May 1978 (6, reproduced).

1986

New English Art Club: Centenary Exhibition, Christie’s, London, August–September 1986 (97, reproduced).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (2, reproduced).

1990

From Beardsley to Beaverbrook: Portraits by Walter Richard Sickert, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, May–June 1990 (8).

1995

Impressionism in Britain, Barbican Art Gallery, London, January–May 1995, Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin, June–July 1995.

References

1891

Gentlewoman, 5 November 1891.

1891

Liverpool Mercury, 21 November 1891.

1891

National Press, 22 November 1891.

1891

Star, 24 November 1891.

1891

Birmingham Post, 27 November 1891.

1891

Standard, 27 November 1891.

1891

Yorkshire Post, 27 November 1891.

1891

Globe, 28 November 1891.

1891

Land and Water, 28 November 1891.

1891

‘In the Picture Galleries: The New English Art Club by a Neo-Anglican’, Pall Mall Gazette, 28 November 1891.

1891

Cicely Carr, Vanity Fair, 28 November 1891.

1891

Herald, 29 November 1891.

1891

Daily News, 30 November 1891.

1891

Star, 30 November 1891.

1891

‘New English Art Club’, Times, 30 November 1891.

1891

Echo, 1 December 1891.

1891

Daily Telegraph, 1 December 1891.

1891

Daily Graphic, 1 December 1891.

1891

Eastern Daily Press, 1 December 1891.

1891

Leeds Mercury, 1 December 1891.

1891

Nottingham Guardian, 1 December 1891.

1891

Bazaar, 2 December 1891.

1891

Sun or Fun?, 2 December 1891.

1891

Hearth and Home, 3 December 1891.

1891

St James’s Gazette, 3 December 1891.

1891

Truth, 3 December 1891.

1891

Anti-Jacobin, 5 December 1891.

1891

Belfast Weekly News, 5 December 1891.

1891

Illustrated London News, 5 December 1891.

1891

Lady’s Pictorial, 5 December 1891.

1891

Piccadilly, 5 December 1891.

1891

‘Art Gossip’, Pictorial World, 5 December 1891.

1891

Spectator, 5 December 1891.

1891

Tablet, 5 December 1891.

1891

Weekly Despatch, 6 December 1891.

1891

Bazaar, 7 December 1891.

1891

World, 9 December 1891.

1891

Daily Telegraph, 10 December 1891.

1891

Pall Mall, 10 December 1891.

1891

Frederick Wedmore, ‘The New English Art Club’, Academy, 12 December 1891.

1891

National Observer, 12 December 1891.

1891

Daily Chronicle, 14 December 1891.

1891

‘Art Notes’, Truth, 17 December 1891.

1891

‘Picture Exhibitions’, Amateur Photographer, 18 December 1891.

1891

Oracle, 19 December 1891.

1891

Life, 26 December 1891.

1891

Saturday Review, 26 December 1891.

1891

Lady, 31 December 1891.

1892

George Moore, Speaker, 20 February 1892.

1895

Yellow Book, vol.4, January 1895, reproduced p.86, as Portrait of Mr. George Moore.

1912

Walter Sickert, ‘The Futurist “Devil-Among-The Tailors”’, English Review, April 1912.

1914

Walter Sickert, ‘The New English Art Club’, New Age, 4 June 1914.

1921

Theodore Galerien, ‘The Renaissance of the Tate Gallery’, Studio, vol.82, no.344, November 1921, p.194.

1927

James Bolivar Manson, ‘Walter Richard Sickert, A.R.A.’, Drawing and Design, vol.3, July 1927, p.4.

1930

Alfred Thornton, ‘Walter Richard Sickert’, Artwork, vol.6, no.21, Spring 1930, p.13, 15.

1938

Alfred Thornton, The Diary of an Art Student of the Nineties, London 1938, p.33.

1939

John Rothenstein, ‘Walter Richard Sickert’, Picture Post, 18 February 1939, reproduced.

1941

Robert Emmons, The Life and Opinions of Walter Richard Sickert, London 1941, pp.87, 89, 96, 98, 101, reproduced opposite p.86.

1943

Lillian Browse and Reginald Howard Wilenski, Sickert, London 1943, p.11.

1955

Anthony Bertram, Sickert, London and New York, 1955, reproduced pl.5.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, pp.22, 100.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.621.

1967

David Sylvester, ‘Walter Sickert: More about the Englishness of English Art’, Artforum, vol.5, no.9, May 1967, p.45.

1971

Marjorie Lilly, Sickert: The Painter and his Circle, London 1971, p.26, 31, reproduced pl.4.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, pp.37–8, 119, 307, no.55, reproduced pl.31.

1976

Denys Sutton, Walter Sickert: A Biography, London 1976, p.52, reproduced fig.15.

1977

Wendy Baron, Miss Ethel Sands and her Circle, London 1977, p.78, reproduced opposite p.220.

1981

Late Sickert: Paintings 1927–1942, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1981, p.91.

1991

Alan Bowness, Judith Collins, Richard Cork et al., British Contemporary Art 1910–1990: Eighty Years of Collecting by The Contemporary Art Society, London 1991, p.20.

1992

Maureen Connett, Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group, Newton Abbott 1992, reproduced p.16.

1992

Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, pp.38, 43, reproduced fig.39.

1998

Lucien Pissarro et le post-impressionisme anglais, exhibition catalogue, Musée de Pontoise 1998, p.36.

2000

Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford and New York 2000, pp.304, 309–10, 375, reproduced fig.23.

2005

Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, London 2005, pp.186, 189–90, 414.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, pp.24–5, no.61.

2006

David Fraser Jenkins, ‘Lies and Statistics’, State of Art, January–February 2006, p.14, reproduced.

2006

Kenneth McConkey, The New English: A History of the New English Art Club, London 2006, p.56, reproduced.

Technique and condition

George Moore is painted on a stretched canvas that at some point during its history was lined, presumably because the original support had deteriorated in condition. The canvas was probably sized but does not appear to have been primed; instead, the artist applied a layer of brown-coloured oil paint directly onto the cloth, to act as an optical ground. Working on an unprimed surface also had several advantages as some of the oil paint would have absorbed into the canvas, affecting the drying, so that Sickert could work quicker and maintain the impression of a lean surface that had not been overworked.

Sickert probably began by blocking in the background first in a fluid dark green paint leaving an area of reserve for the portrait. He built up the sitter’s face by applying patches of flesh-coloured paint leaving the optical ground exposed to function as a mid-tone. The portrait was probably worked in several stages, allowing the paint to dry before applying final fluid strokes in an impressionist style building to a low impasto in areas such as the brow and cheeks. The sitter’s jacket appears to have been blocked in black paint, leaving an area of reserve for his necktie and collar, which were later worked in a few economical brushstrokes over the lean dried paint, at which time the jacket may also have been repainted.

The background was repainted in the later stages to redefine the boundaries of the portrait, and the form of the sitter’s head was then adjusted by applying a more opaque paint with white admixture around the back of the head in the same colour as the background. The painting was probably originally varnished by the artist but may have been subsequently re-varnished to improve the saturation of the dark colours.

Sarah Morgan

June 2006

How to cite

Sarah Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', June 2006, in Robert Upstone, ‘George Moore 1890–1 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

George Augustus Moore (1852–1933) was born at Moore Hall, Lough Carra, County Mayo, Ireland. His father, George Henry Moore (1810–1870), was a gentleman horse breeder and Member of Parliament. While the family were living in London, George Moore decided he wanted an artistic career and so enrolled as an art student in 1868, a move bitterly opposed by his parents who wanted him to join the army. The early death of Moore’s father in 1870 allowed him freedom to follow his desire, as well as the income from the family estate in Ireland.

Edouard Manet 1832–1883

George Moore 1873–9

Pastel on canvas

552 x 352 mm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs H.O. Havemeyer, 1929

Photo by Malcolm Varon © 2011. The Metropolitan Museum of Art / ArtResource / Scala, Florence

Fig.1

Edouard Manet

George Moore 1873–9

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs H.O. Havemeyer, 1929

Photo by Malcolm Varon © 2011. The Metropolitan Museum of Art / ArtResource / Scala, Florence

Moore returned to London in 1880, producing a series of novels, including the famous Esther Waters (1894), while also turning his attention to writing on art.2 As art critic of the Speaker he championed Manet and Degas, and modern French art as a whole. When he moved to the Saturday Review, Moore nominated Walter Sickert to replace him. In 1891 Moore published Impressions and Opinions, which included colourful essays on Zola, Verlaine, Honoré de Balzac, Arthur Rimbaud and Jules Laforgue, while his 1893 Modern Painting established him as the chief apologist for new developments in art. In this period his and Sickert’s views on art almost exactly coincided.

Sickert and Moore first met in Dieppe, an occasion Moore recalled with Proustian intensity even decades later:

I had come over from London to spend a week with Jacques Blanche ... and was talking in the dining room with him and his mother about the tapestry they were lucky to come upon in an old shop. How precise and vague memory is! I can see the colour, every shade of the green, but nothing of the design; and the table, too, already laid, the napery, glass and silver catching the light, is part of my impression of Sickert coming in at the moment of sunset, his paint-box slung over his shoulders, his mouth full of words and laughter, his body at exquisite poise, and himself as unconscious of himself as a bird on a branch. No, I don’t think anybody was ever as young as Sickert was that day at Dieppe. A few months afterwards in London he shaved his moustache, a frizzle of gold – God only knows why!3

Exhibition

That Sickert should paint a portrait of a friend who shared his artistic beliefs is not surprising. But it must be that he also intended to raise and commemorate the status of Moore as a critic and supporter of new British art, and by implication his own status as an artist. It is difficult not to see such a work as reinforcing a tribal sense of belonging to a defined avant-garde group in the British art world. That Sickert’s George Moore was first shown at the 1891 exhibition of the New English Art Club – in which Sickert was a leading member of a hard-line impressionist faction which Moore had defended in print – would seem to confirm the portrait as part of Sickert’s campaign. It may have been seen as a provocation by more conservative critics, and also elements of the New English Art Club itself. Stanhope Forbes, for instance, had been a founder of the NEAC, but bitterly tried to resist the more authentically impressionist direction in which Sickert and Steer tried to take the group. He effectively withdrew from the debate when he became an Associate Royal Academician in 1892. The potential of Moore’s portrait to irritate conservative elements is borne out by Robert Emmons’s recollection that at the annual Royal Academy banquet, presumably during the speeches, it was derided as an ‘intoxicated mummy’,4 reputedly by Henry Butcher.5

Further evidence that Sickert was using such pictures to elevate the status of the new art protagonists is that in 1890, the year before he exhibited George Moore, he and Steer each painted a portrait of one another and showed them at the New English Art Club spring exhibition (Sickert’s portrait of Steer is now in the National Portrait Gallery,6 while Steer’s painting of Sickert is now lost).7 Indeed, the Umpire complained:

The members of this club paint each other, make presents to each other, pervade the rooms talking of each other, and lend each other’s pictures. Still, among a good many specimens of the ‘smudgy’ and ‘blobby’ school who hurl a pot of paint at a square of canvas and call it ‘an impressionist sketch’ ... among such amiable vagaries hang some dozen examples of astonishingly good work.8

Around the time he exhibited George Moore, Sickert was heavily engaged in the discipline of making portrait studies. In 1890 he was commissioned to make a series of drawings from life of familiar society figures for full-page reproduction in the short-lived weekly journal the Whirlwind. He submitted an illustration each week, and the diverse figures that he represented included Jacques-Emile Blanche, Charles Bradlaugh, Henry Labouchere, Lord Lytton and Sir Charles Rivers Wilson.9 In 1893 the Pall Mall Budget reprinted three drawings from the Whirlwind series, and also others probably drawn in 1890 that included Lord Curzon, Hippolyte Taine and Professor Dewar.

In the 1890s celebrity was big business. Britain was a society dominated by mass production and the beginnings of a collective mass culture, one effect of which was the celebration of individuality and fame. People hungrily consumed images of their heroes in newspapers and journals, searching for the physiognomy of genius. The refinement of printing technology in the 1890s allowed artists’ drawings to be reproduced through photographic processes. Images of the great and the good were commissioned from artists, often with the belief that greater revelation of character would come through their perceptive translation than through a photograph. Series such as William Rothenstein’s English Portraits or William Nicholson’s Twelve Portraits, both published in 1897, were eagerly consumed and sold in large numbers.

Reception

Sickert’s head and shoulders drawing in pen and ink of George Moore appeared in the Pall Mall Budget on 23 February 1893, and a three-quarter-length drawing was reproduced in the Cambridge Observer, edited by his brother Oswald, on 28 February 1893. As the art historian Wendy Baron has suggested, it seems possible that both these drawings were done in 1890, at the same time Sickert was working on his oil portrait, although neither is a study for it.10 In his review of Sickert’s essay ‘Realism in Painting’, Moore wrote of his experience of being painted by Sickert, and related it to the argument of Sickert’s article:

The great meaning – the essential meaning – of Mr Sickert’s essay may be summarised in this way: – Observe nature, study nature; but do not copy nature. And for many years Mr Sickert has practised what he preaches. He had made thousands of drawings in the fields and streets, in the theatres and music-halls; he has perfected his memory by constant application, and his pictures are painted from studies. I only sat twice for the astonishing and now celebrated portrait, and when, owing to a press of work, I was compelled to abandon the sittings, the portrait was chaos. But Mr Sickert had got from me all he wanted, and so was free to pursue the artistic ideal he was striving for ... Mr Sickert must not forget that the artist need not copy the model, even though the model is always before him while he is painting.11

The portrait of Moore attracted considerable and extensive attention in the press, some favourable and some heavily critical. The Yorkshire Post described it as ‘an astonishing portrait ... which it is impossible to believe is seriously intended’,12 while the Liverpool Mercury noted, ‘Mr Walter Sickert has painted Mr George Moore in somewhat eccentric style’. 13 Other reviewers responded to what they believed was the impressionist technique Sickert employed, and thought it looked better viewed from further away:

Perhaps the most contentious picture ... is Mr Walter Sickert’s portrait of Mr George Moore, who by one paper was likened to a ‘boiled ghost’. It is true that the near effect of ‘GM’s’ features is ghastly, as they are reproduced by a few bold dashes of Mr Sickert’s brush, but the distant effect is undeniably life-like. The philistine spectator must be educated in impressionism before he can thoroughly appreciate it.14

The Times judged this technique less praiseworthy:

A notable but unpleasing picture ... It is excessively dexterous and careless; but, if it fairly illustrates the Impressionist method of portraiture, one can only say that a portrait should not appear to be the work of a ‘lightening artist’, but should record, as all great portraits do, more than a passing mood or a transient expression.15

The Echo took up this point, but defended Sickert’s ability to capture Moore’s character:

It is a head and bust portrait snatched by what are known as impressionistic means. Seen from across the room, it certainly conveys with startling veracity the impression of the exaggerated blonde; but this is not all. The artist has unquestionably had a sudden glimpse of the inner character of his sitter, which he has revealed with more fidelity than compassion.16

Several newspapers suspected Sickert had painted something that deliberately bordered on parody. The Pall Mall Gazette wrote of it as ‘a portrait as might be said by some to approach a caricature of the sitter’s genial features; but there is no denying the vividness of the impression conveyed’,17 while the Birmingham Post thought Moore ‘must feel but slightly flattered by the portrait ... which occupies a central position in the gallery’.18 The critic of the Herald poked fun at both Sickert’s abilities as a portraitist and Moore’s advocacy of French naturalist literature:

The spirit and waggery of the new English artists has not entirely departed, for is there not left to us a perfectly humorous portrait of Mr George Moore, whose sightless orbs notwithstanding, seems to have been brought face to face with all the horrors and remorse of ‘Thérese Racquin’, and appears to be suffering from violent jim-jams?19

The idea that the picture was some sort of caricature was pursued in a number of notices. The Echo critic wrote how they

nearly expired over the portrait of a novelist man ... Some said it looked like a boiled ghost, but he might have added the word ‘soiled’ as well. It is a tremendous joke, and it was delicious to see people come up in front of it, glance at it, examine their catalogues, and then gradually alter their expression from a puzzled, revolted wonder to subdued mirth. People brought others to see, and small explosions of laughter were heard in the vicinity; but, of course, we were all afraid to laugh openly, lest the artist should be close to us. He must have been suffering from a nightmare when he painted that awful head.20

Perhaps because of its notoriety or celebrity, Sickert is said to have placed a price on the portrait of a hundred guineas when it was exhibited in 1891.21 While critical reactions were distinctly mixed, most commentated upon the work’s ability to express a distinct character. D.S. MacColl in the Spectator wrote most favourably:

It is a work that gives three several satisfactions. From a due distance it attracts first by its design and colour, and then arrests by its extraordinary expressiveness. Whether or not it is like its original, it is a notable piece of character-painting, and suggests how powerful a weapon lies in the hand of the painter if he chooses, in paint, to criticize the critic. But there is a third pleasure ... the handling, – how the drawing is built up, the deliberate skill and subtlety of the touches.22

Moore was certainly a man of singular and characterful appearance, to which his obituary in the Times drew attention:

In person he was of middle height, with fresh complexion, sloping shoulders, long, sensitive hands which he employed continually in limp gestures, hair once yellow and afterwards white, and a moustache that partly hid the arrogant, sensual mouth; but nothing hid the changes of his eye, which was now soft and gentle, and anon – at a challenging thought – sharp as a hawk’s. He was never a great reader or a tolerant one. It pleased him to insist on unexpected preferences.23

Moore’s own reactions to his portrait were not voiced publicly until 20 February 1892, when in the Speaker he pronounced himself satisfied. But the lapse in time before mentioning it in print adds credence to the story that he was privately very annoyed by the picture. According to James Laver, when he first saw the picture he exploded, ‘You have made me look like a booby!’ Sickert is reputed to have responded, ‘But you are a booby’.24

The beginnings of the waning of Sickert’s admiration for Moore might be seen in the caricature he published of him in Vanity Fair in 1897, which he titled Esther Waters, the same as the eponymous servant heroine of Moore’s most famous novel, who endured unmarried pregnancy and hardship.25 Robert Emmons wrote that ‘To Sickert, Moore was always a subject of gay derision. His pronouncements on painting were reassured as delicious titbits of the sublimely ridiculous.’26 After Moore published Conversations in Ebury Street in 1924, which contained a chapter about the painter, ‘Sickert never forgave him’ and considered the text ‘only just short of actionable’.27

Ownership

Robert Emmons said Sickert wrote to Steer requesting George Moore for his December 1900 solo exhibition held at Durand-Ruel’s gallery in Paris, where he was with Moore: ‘Send me George Moore’s portrait for my exhibition,’ Sickert wrote, ‘I will take care of it and send it back promptly. Send it quickly.’28 Although it is not listed as being included in the show, it at least indicates that by 1900 Steer was already in possession of the picture, and it might be supposed he obtained it from Sickert some time following the 1892 New English Art Club exhibition. Emmons added that ‘Sickert had a particular admiration and affection for Steer ... It was a great pleasure to him when Steer later gave his portrait of George Moore to the Tate, thus linking their names together forever.’29

The impetus behind the gift – which was through the Contemporary Art Society, formed in 1910 – appears to have been the critic D.S. MacColl, who recalled the portrait being on Sickert’s easel when he first visited him in 1891. ‘I prevented him from spoiling it,’ MacColl recalled, ‘and had that personal reason, as well as its merit, for wishing to secure it for the Tate Gallery.’30 MacColl reprinted a letter from Sickert to Steer about the gift through the Contemporary Art Society:

My dear Steer

Do you think

Firstly that when MacColl suggested your giving my head of the George Moore that he meant he would accept it? Or do you think it was merely a polite boutade without any consequence?

Secondly, if he would, would you do this handsome thing and present it? It would be agreeable and useful to me and the more agreeable part would be the public association for ever of your name as a donor and a picture of mine. A sort of crystallisative reminder of the to me agreeable fact that our names have from the beginning been very much linked together.

If the answer to my second question is affirmative sound him next time you see him as from yourself – not as from me. If he were disinclined, I may be supposed to have no cognizance of the scheme. ‘Sly’ ‘devilish sly’ is for Bagstock.31

MacColl incorrectly dates this letter to 1917. But Steer was reported to have already presented the picture to the Contemporary Art Society in the 1912 edition of This Year’s Art,32 suggesting that he donated it sometime between that date and the Society’s formation in 1910. In a letter to his friends Nan Hudson and Ethel Sands, that may date from December 1910, Sickert himself wrote:

This last comment is intriguing as it not only suggests Sickert expected to gain payment by some means, but appears to raise the possibility that although the picture was in Steer’s possession it still belonged to Sickert in some way, so that he could expect payment.

In 1973 Sotheby’s sold a picture by Sickert they titled Portrait of a Man with a Moustache, called George Moore c.1896–8 (private collection),35 but which may perhaps depict the painter Theodore Roussel.

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

R.S. Becker, The Letters of George Moore 1863–1901, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Reading 1980, pp.313–5.

‘In the Picture Galleries: The New English Art Club by a Neo-Anglican’, Pall Mall Gazette, 28 November 1891.

Herald, 29 November 1891; the writer is alluding to Émile Zola’s novel Thérèse Raquin (1867), in which the murderer, Laurent, is an artist all of whose paintings in some way resemble his victim.

James Laver, Museum Piece, London 1963, p.93; quoted in Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, London 2005, p.189.

Ibid., p.96. Steer actually presented the painting c.1911 to the Contemporary Art Society, which gave it to the Tate Gallery in 1917.

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘George Moore 1890–1 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www