Walter Richard Sickert L'Armoire à Glace 1924

Walter Richard Sickert,

L'Armoire à Glace

1924

This finished oil is loyal in appearance and composition to the etching of the same name. It looks through the doorway of a room in Walter Sickert’s seaside flat at 44 Rue Aguado in Dieppe. Reprising the theme of working class subjects within domestic interiors from his Camden Town period, Sickert’s model is the French peasant Marie Pepin, his servant and sole companion at the time. Sickert’s title, which translates as The Mirrored Wardrobe, lends the picture a narrative quality. As a French urban petite bourgeoisie character, Marie sits demurely in shadow, deferring pictorial space to the prized piece of furniture to her right.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

L’Armoire à glace

1924

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 381 mm

Inscribed by the artist in black paint ‘Sickert.1924.’ bottom left and ‘The French Wardro[be]’ on back

Purchased (Knapping Fund) 1941

N05313

1924

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 381 mm

Inscribed by the artist in black paint ‘Sickert.1924.’ bottom left and ‘The French Wardro[be]’ on back

Purchased (Knapping Fund) 1941

N05313

Ownership history

Bought from the artist by William Henry Stephenson, Southport, 1924, from whom bought by Tate Gallery 1941.

Exhibition history

1925

Twenty-Second Exhibition of the London Group, R.W.S. Galleries, London, June 1925 (73).

1941–2

Sickert, National Gallery, London, August–December 1941, Temple Newsam, Leeds, January–March 1942 (94).

1942

The Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions, National Gallery, London, April–May 1942 (120).

1942–3

A Selection from the Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions, (Council for the Encouragement for Music and the Arts tour), Royal Exchange, London, July–August 1942, Cheltenham Art Gallery, September 1942, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, October 1942, Galleries of Birmingham Society of Arts, November–December 1942, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, January–February 1943, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, February–March 1943, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, March–April 1943, Manchester City Art Gallery, April–May 1943, Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool, May–June 1943, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, June 1943, Glasgow Museum and Art Gallery, Kelvingrove, July 1943, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, August 1943 (82).

1946–7

Modern British Pictures from the Tate Gallery, (British Council tour), Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, January–February 1946 (89), Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, March 1946 (89), Raadhushallen, Copenhagen, April–May 1946 (89), Musée du Jeu de Paume, Paris, June–July 1946 (89), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Berne, August 1946 (92), Akademie der Bildenden Kunste, Vienna, September 1946 (93), Narodni Galerie, Prague, October–November 1946 (93), Muzeum Narodwe, Warsaw, November–December 1946 (93), Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Rome, January–February 1947 (93), Tate Gallery, London, May–September 1947 (5313).

1957

Sickert: An Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings and Prints, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, August–September 1957 (60).

1971

Painting and Perception, MacRobert Centre Art Gallery, University of Stirling, October–November 1971 (27).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (23, reproduced on front cover).

1994–5

Eredità dell’impressionismo 1900–1945: La realtà interiore, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome, December 1994–February 1995 (108, reproduced p.182).

1998

Two British Impressionists: Walter Sickert and Philip Wilson Steer, Norwich Castle Museum, January–April 1998 (29, reproduced).

2004

Walter Richard Sickert: The Human Canvas, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, July–October 2004 (35, reproduced).

2007

Il Settimo splendore: La Modernità della malinconia, Palazzo della Regione, Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Verona, March–July 2007 (87, reproduced).

References

1936

William Henry Stephenson (ed.), Sickert, the Man and his Art: Random Reminiscences, privately published 1936, [p.32].

1940

William Henry Stephenson (ed.), Sickert, the Man and his Art: Random Reminiscences, expanded edn, Southport 1940, pp.15–17.

1941

Robert Emmons, The Life and Opinions of Walter Richard Sickert, London 1941, pp.188, 306–7.

1943

Lillian Browse and R.H. Wilenski, Sickert, London 1943, note to pl.57 and p.60.

1949

Notes and Sketches by Sickert from the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1949, pp.18, 20.

1955

Anthony Bertram, Sickert, London and New York 1955, p.6, reproduced pl.43.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, pp.37, 102.

1964

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942: A Handbook to the Drawings, Paintings, Etchings, Engravings and other Material in the Possession of the Islington Public Libraries, London 1964, [p.4].

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.635.

1968

Malcolm Easton, Sickert in the North, exhibition catalogue, University of Hull 1968, p.v.

1970

Our Own Sickerts: An Exhibition of Drawings, Paintings and Etchings from the Collection of Islington Libraries, exhibition catalogue, Islington Libraries, London 1970, p.5.

1970

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942: Catalogue of the Islington Libraries Collection, London 1970, p.5.

1971

Marjorie Lilly, Sickert: The Painter and his Circle, London 1971, pp.60–1, reproduced pl.18.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, p.162, no.388, reproduced fig.271.

1975

Wendy Baron, Sickert in Dieppe, exhibition catalogue, Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne 1975, p.8.

1976

Denys Sutton, Walter Sickert: A Biography, London 1976, p.211.

1980

Wendy Baron, ‘The Perversity of Walter Sickert’, Arts Magazine, vol.55, no.1, September 1980, p.127, reproduced fig.8.

1987

David Withey, The Sickerts in Islington, exhibition catalogue, Islington Libraries, London 1987, p.4.

1992

Wendy Baron and Richard Shone (eds.), Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, p.278.

2000

Ruth Bromberg, Walter Sickert Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven and London 2000, pp.38, 250, reproduced fig.17.

2003

Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits, exhibition catalogue, National Portrait Gallery, London 2003, p.118.

2005

Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, London 2005, pp.525–6.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.557, pp.111, 130, 140, 479, reproduced.

Technique and condition

L’Armoire à glace is painted on a pre-primed canvas purchased in Dieppe from the French colourman E. Clouet. The fine open-weave canvas is on a standard dimension French stretcher with fixed corners, which has subsequently been cut down on one side and the canvas trimmed on one side to fit the new dimension before it was re-stretched. The original dimension of the strainer was a standard French size (see Tate N03182) either 610 x 460 mm (Size number 12, Paysage) or 610 x 500 mm (Size number 12, Figure). It is now 610 x 380 mm (Size number 12, Marine, used vertically). The reduced canvas tacking edge has blue and grey pencil marks at 20 mm intervals, but these do not appear to extend to a grid under the painting. It is possible that Sickert made an initial sketch or drawing to fit the known marine dimensions but could not buy a corresponding strainer so had one modified to fit the drawing.

The artist has drawn directly onto the white primer with a brush in a strong brown/pink oil paint to roughly define the armoire, bed and floor. It is possible to see white paint and a lighter pink in areas, particularly in the small gaps between the applications of later layers of paint. A few areas are left thin with the canvas texture evident, but most have thicker paint with some impasto. There is some wet-in-wet mixing in the final stages, but the canvas appears to have been allowed to dry between its two (or three) main stages. Harry Rutherford, a pupil of Sickert at the Manchester Painting School in 1925, recalled how:

Sickert could not emphasise too strongly the importance of a bone-dry working surface ... If possible, a canvas should be put aside for twelve months following the first application of paint. More often, in an imperfect world, three weeks had to suffice, and evening students were permitted to continue after the mere seven days that separated class from class.1

In general, the paint is more smoothly brushed than some other works, but brushmarking is evident in defining the furniture. The paint appears to have been mixed from the tube and applied relatively leanly. It is pre-mixed on the palette in subdued tones and colours, although with a strong green cast. The painting is varnished, although it is not known whether the varnish was originally applied by the artist.

Stephen Hackney

June 2004

Notes

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', June 2004, in Nicola Moorby, ‘L’Armoire à glace 1924 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, March 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

L’Armoire à glace (The Mirrored Wardrobe), is one of a series of works from 1921–4 in which Walter Sickert returned to and reprised a favourite theme from his earlier Camden Town period, that of the domestic interior. The painting shows a glimpsed view through an open doorway of a woman seated in a darkened bedroom. She is partially hidden behind a large wardrobe with a mirrored door in which is reflected part of her arm and the bed on the opposite side of the room. The woman is wearing a light coloured dress and blue-grey boots and is sitting with her hands folded in her lap. The features of her face have been left unresolved. The colour palette of the painting is similar to that of Ennui c.1914 (Tate N03846), with yellow, orange and brown dominating the composition. Sickert first represented the image as an etching, L’Armoire à glace, dated 1922,1 and there are a number of related preparatory sketches (see Tate N05312 and N06087, figs.1 and 2). A full list can be found in Wendy Baron’s 2006 catalogue.2 The painting, inscribed on the canvas 1924, reproduces exactly the appearance and composition of the etching except that the edge of the door and doorknob are omitted from the right-hand edge of the painted work.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Study for 'L'Armoire à glace' 1922

Graphite, ink, watercolour and gouache on paper

support: 260 x 187 mm

Tate N05312

Purchased 1941

© Tate

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Study for 'L'Armoire à glace' 1922

Tate N05312

© Tate

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Study for 'L'Armoire à Glace' c.1922

Ink on paper

support: 281 x 132 mm

Tate N06087

Presented by Roland, Browse and Delbanco 1952

© Tate

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

Study for 'L'Armoire à Glace' c.1922

Tate N06087

© Tate

In common with paintings from around 1910–14 such as Ennui, the setting for the subject was an address occupied by Sickert himself, although in this case the artist was not in residence in London, but in Dieppe. The precise location is revealed as an inscription on the third state of the etching: on the bottom right-hand corner of the plate is written ‘Rue Aguado’. This refers to 44 Rue Aguado, a seafront flat in Dieppe where Sickert leased rooms during 1921–2.3 His only companion at this time was Marie Pepin, a French peasant whom Sickert had first employed as a servant while he and his wife were living at Envermeu in 1913. Pepin was the Gallic counterpart of her Camden Town namesake, Marie Hayes (see Tate N03846). She was extremely loyal to the Sickerts, even returning to London with them during the war despite the fact that she did not speak English, and she later nursed Christine Sickert in her final illness. After Christine’s death in 1920 Marie stayed on with Sickert and played an important role in looking after the bereaved and depressed artist, accompanying him when he moved from Envermeu to Dieppe in 1921. By the summer Sickert had rallied sufficiently to begin working again in earnest. He wrote to his sister-in-law, Andrina Schweder: ‘I have sittings by electric light nearly every day in [the] flat at No.44 and am deep in figure subjects again.’4 He employed Marie’s niece as a model, and later persuaded Marie herself to sit for him. According to the art historian Lilian Browse, Marie was the model for L’Armoire à glace.5 The acidic oranges and yellows and dark contrasting shadows may be a response to working by the harsh glare of electric lighting.

In his domestic interiors Sickert distils an impression of contemporary society. The Camden Town Murder series and other paintings from the same period immortalise London’s working and lower middle classes. Similarly, L’Armoire à glace and other related Dieppe subjects portray the lives of the French urban petite bourgeoisie. In a letter to the first owner of the painting, W.H. Stephenson, Sickert described the work as

a sort of study à la Balzac. The little lower middle-class woman in the stays that will make her a client for the surgeon and the boots for the chiropodist, fed probably largely on ‘Ersatz’ or ‘improved’ flour, salt substitutes, dyed drinks, prolonged fish, tinned things, etc., sitting by the wardrobe which is her idol and bank, so devised that the overweight of the mirror-door would bring the whole structure down on her if it were not temporarily held back by a wire hitched on an insecure nail in insecure plaster. But a devoted, unselfish, uncomplaining wife and mother, inefficient shopper and atrocious cook.6

The passage expounds upon the prosaic theme hinted at in the title, that of the mild poverty of one woman’s life and her disproportionate pride in a prized piece of furniture, her mirrored wardrobe. A touched proof of the first state of the etched version bears the inscription, ‘Mon rêve ça a toujours été d’avoir une armoire à glace’ (My dream has always been to have a mirrored wardrobe). Furthermore, a study in watercolour, Mon Rêve: Study for ‘L’Armoire à glace’ (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston),7 also bears a similar annotation: ‘Moi depuis que j’ai mon armoire à glace je suis contente’ (Since I have had my mirrored wardrobe I am content).

It was unusual for Sickert to provide such a full narrative accompaniment to one of his paintings, but in the letter he is deliberately drawing attention to his ability to create verisimilitude and biography within a visual form. He himself described ‘the wealth of Balzac’ as ‘immense accumulations of intellectual riches ... dominated by a city of sumptuous palaces, but each palace is stiff with a mass of detail, each detail again complete in itself, and each one carrying in itself innumerable seed for the future to develop into the infinity of time and to the unfathomable limit of human achievement.’8 The deliberate reference to the writer, Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850), in the letter to Stephenson is revealing and an endorsement by the artist of the literary or narrative component of his art and a further pledge of loyalty to traditional French culture. In the series of novels known as the Comédie humaine (1830–46), Balzac surveyed French society, looking critically at the intermingled motives of financial greed, social snobbery and sexual desire. Several characters reappear over the course of different novels, re-entering the main action of the plot or simply figuring in the background. In particular, the author was renowned for his discerning observation and incisive portrayal of contemporary life, a characteristic that would be described in English literature as ‘Dickensian’. Balzac described the accessories of modern life in detail, often as evidence of the morals of their owners. The furniture of Monsieur Marneffe and his wife Valérie in Cousin Bette (1846), for example, is described at length in terms of the contrast between his shabby rooms and her more refined boudoir:

La chambre de monsieur, assez semblable à la chambre d’un étudiant, meublée de son lit de garçon, de son mobilier de garçon, flétri, usé comme lui-même, et faite une fois par semaine ... La chambre de madame faisait exception à la dégradante incurie qui déshonorait l’appartement officiel ... élégamment tendus en perse, à meubles en bois de palissandre, à tapis en moquette ... Le lit, la toilette, l’armoire à glace, le tête-à-tête, les colifichets obligés signalaient les recherches ou les fantaisies du jour.

(The master’s room, not unlike the room of a student, was furnished with his single bed, the furniture of his bachelor days, faded and shabby like himself, and cleaned once a week ... The mistress’s room was the exception to the degrading neglect that dishonoured the common living-rooms ... elegantly furnished with chintz and rosewood furniture, and a pile carpet ... The bed, the dressing-table, the wardrobe with a mirror, the small sofa, and all the trifles strewn about, were in the style of the latest novelties of the moment.)9

Balzac hints that the extravagance of Madame Marneffe was paid for by a lover.

Sickert also exploits details to reveal social class within an implied narrative, as if his scenes were illustrations of a novel. The story in this painting is intimate, with an empty bed seen (in a not very convincingly arranged reflection) at the same time as the elderly woman. The mirror also is a traditional symbol of vanity and fickleness in love. The situation is unsettling for the viewer, as the woman looks like a chaperone or even the madame of a brothel. The visual suggestion that the ambitions of common taste are somehow linked with sexual infidelity has a parallel to a similar attitude in the novels of Balzac. Many critics, naturally unaware of the artist’s letter to Stephenson, drew parallels with the French author regarding this and other paintings. The New Statesman argued that Sickert demonstrated ‘a Balzacian sense’ of ‘the interpretation of life’,10 while the critic in the Queen declared, ‘Many a Balzacian development might find its starting point in one of Mr Sickert’s ... interiors’.11 The level of detail Sickert chooses to invent in the letter about L’Armoire à glace is equivalent to the content of Virginia Woolf’s 1934 essay in which she invents a story around some of Sickert’s paintings, including, most famously, Ennui.12 Sickert encouraged Woolf in her venture writing to her, ‘I have always been a literary painter, thank goodness, like all decent painters. Do be the first to say so.’13

While the environment Sickert creates is accurately representative of a certain sector of society, the narrative specifics of the scene remain ambiguous. It is unclear, for example, whether the woman is sitting placidly beside her wardrobe or trying to cower behind it. An indication that Sickert might have had other anecdotal scenarios in mind for L’Armoire à glace can be inferred from a pair of related drawings. Both bear titles inscribed by the artist: Le Sourire d’Almaviva; Study for ‘L’Armoire à glace’ (Almaviva’s Smile) c.1922 (pen and dark green ink and chalk on paper, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester);14 and a squared-up drawing known as Study for Prout’s Parlour c.1922 (pen and black ink on paper, private collection).15 The reference in the former is to Almaviva, a character in Mozart’s opera The Marriage of Figaro and also in The Barber of Seville by Rossini. Sickert’s drawing of a woman pressed into the corner of a bedroom possibly assumes the predatory sexual viewpoint of this philandering Spanish count. The title of the latter drawing is derived from a handwritten inscription on the side of the work which has been interpreted as ‘Prout’s Parlour’ but perhaps could be read as ‘Proust’s Parlour’. It is not known whether Sickert ever met the French writer Marcel Proust (1871–1922), but both were certainly aware of each other.16 Sickert read À la Recherche du temps perdu as it appeared in its various instalments, and in a letter to Mrs Swinton declared it to be ‘the book of the century’.17 Proust’s death in November 1922 perhaps accounts for his intrusion into Sickert’s thoughts.

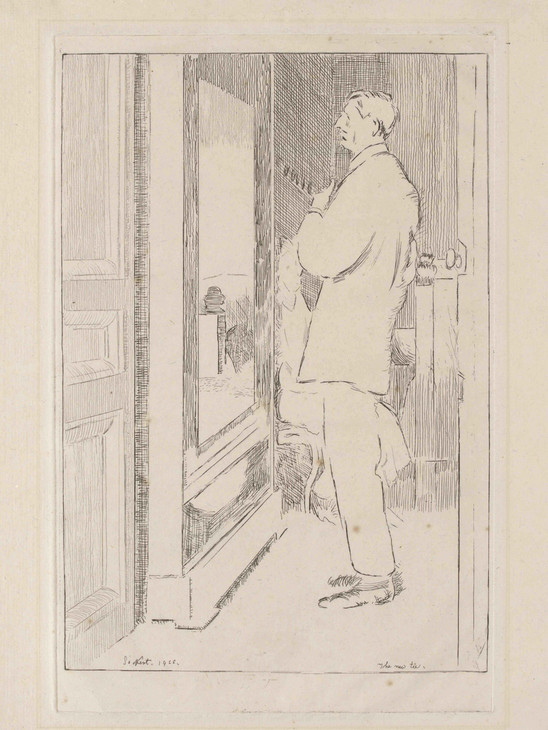

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The New Tie 1922

Etching on paper

358 x 237 mm; plate-mark 275 x 177 mm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

The New Tie 1922

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

William Henry Stephenson, a newspaper magnate from Southport, first met Sickert in 1923 when he sought out the artist’s studio at 15 Fitzroy Street on a trip to London.25 At this time Sickert was still struggling to come to terms with the death of his wife, Christine, and was living as something of a recluse, painting little and not taking a great deal of care of himself. Stephenson’s visit and subsequent friendship seems to have had some impact on revitalising the artist’s spirits and energies. Stephenson informed him that the Southport Art Gallery had recently acquired one of his early paintings, Amphityron, and persuaded him that far from being forgotten, his work was of interest to collectors in the north of England. He invited Sickert to lecture in Southport and later agreed to publish a series of articles by the artist in the newspaper he directed, the Southport Visiter. In 1924 he purchased L’Armoire à glace from the artist. In gratitude for these small but significant acts of friendship and support, Sickert also presented Stephenson with one of the preparatory working drawings for the subject. He inscribed the study ‘to W.H. Stephenson in grateful sympathy Walter Sickert’.

Stephenson had a very high opinion of Sickert and his work and was instrumental in introducing his name for election to the Royal Academy (an honour which Sickert greatly desired at this time although he later resigned as a gesture of protest). In 1936, and again in 1940, Stephenson compiled and privately published some Random Reminiscences of his dealings with the artist, including private letters he had received and the Southport Visiter articles. He introduced his essay in the 1940 edition with some lines from an article in the Daily Mail, 14 November 1930, which suggested that the most fitting way to honour the country’s ‘greatest living painter’ was to ‘hold a truly representative collection of his works at the Tate Gallery’.26 Stephenson was obviously keen to make his own contribution to ensuring Sickert was well represented in the national collection. Just a year later, in 1941, he sold L’Armoire à glace to the Tate Gallery.

Nicola Moorby

March 2005

Notes

Reproduced in Ruth Bromberg, Walter Sickert Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven and London 2000, no.200.

Walter Sickert, letter to W.H. Stephenson, undated [1924]; quoted in William Henry Stephenson (ed.), Sickert, the Man and his Art: Random Reminiscences, expanded edn, Southport 1940, p.17.

Walter Sickert, ‘The True Futurism’, Burlington Magazine, March 1916, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, pp.404–5.

Quoted in Stella Tillyard, ‘The End of Victorian Art: W.R. Sickert and the Defence of Illustrative Painting’, in Brian Allen (ed.), Towards a Modern Art World, New Haven and London 1995, p.190.

Baron 2006, no.557.8; reproduced in Walter Sickert: ‘drawing is the thing’, exhibition catalogue, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester 2004 (3.11).

Related biographies

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘L’Armoire à glace 1924 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, March 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www