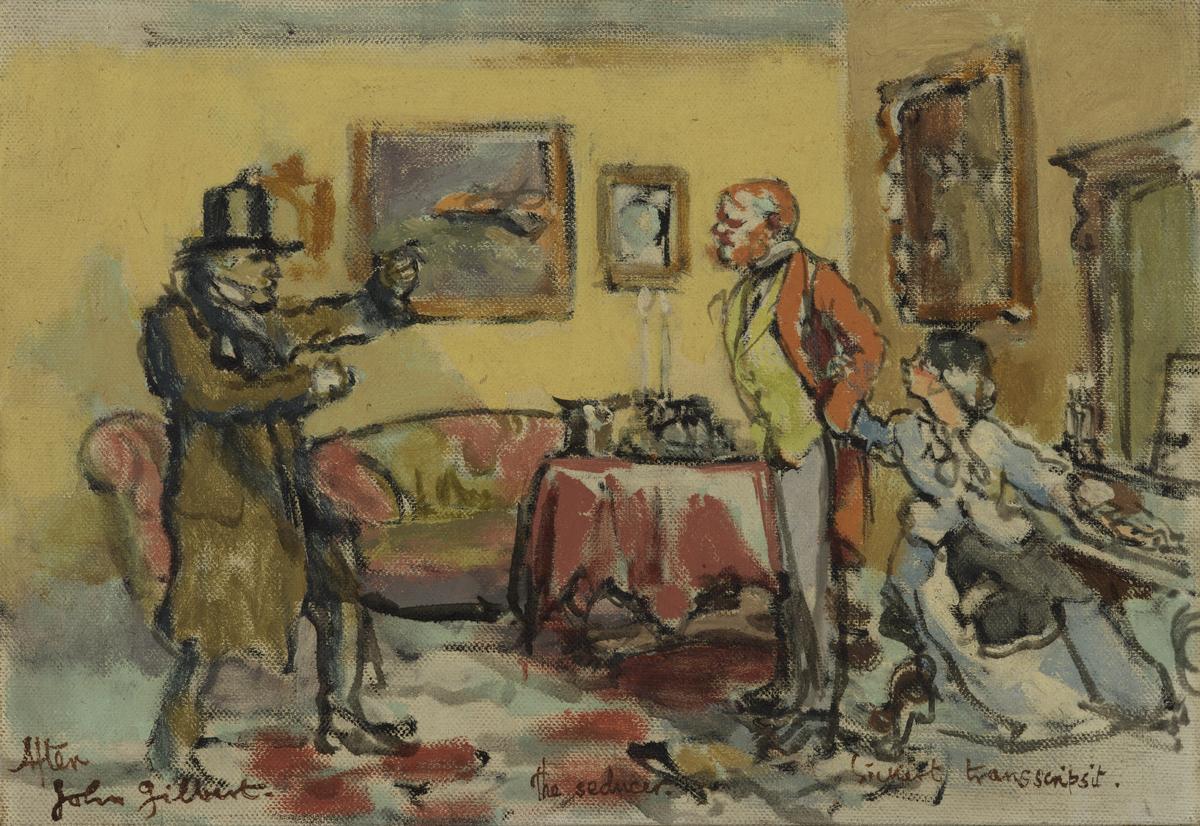

Walter Richard Sickert The Seducer c.1929-30

Walter Richard Sickert,

The Seducer

c.1929-30

This late work by Sickert is part of the ‘Echoes’ series of around a hundred paintings which draw from designs found in old editions of the London Journal, Illustrated London News and other nineteenth-century periodicals. The pictures pay homage to Victorian illustrations by artists including John Gilbert, as in this painting, whom Sickert met as a young draughtsman and long admired.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Seducer

c.1929–30

Oil paint on canvas

425 x 625 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert trans scripsit.’ bottom right, ‘the Seducer.’ bottom centre and ‘After ¿John Gilbert.’ bottom left

Purchased (Grant-in-Aid) 1989

T05529

c.1929–30

Oil paint on canvas

425 x 625 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert trans scripsit.’ bottom right, ‘the Seducer.’ bottom centre and ‘After ¿John Gilbert.’ bottom left

Purchased (Grant-in-Aid) 1989

T05529

Ownership history

Savile Gallery by 1930; ... ; purchased at the Adams Gallery, London, November 1949 by John W. Blyth (1873–1962), Kirkcaldy; sold by order of his legatees Sotheby’s, London, 15 April 1964 (19), bought Ellis for £300; sold Sotheby’s, London, 15 December 1965 (31) for £140; ... ; Mrs Behr, her sale, Sotheby’s, London, 23 April 1969 (25), bought D. Gray for £200; ... ; David Praed, from whom bought by Lady Simone Warner 1969; her sale Christie’s, London, 10 June 1988 (359), bought in at £3,200; her sale Christie’s, London, 3 March 1989 (315), bought Tate Gallery for £3,345.

Exhibition history

1930

Paintings by R. Sickert, A.R.A, Savile Gallery, London 1930 (26, reproduced).

1938

Contemporary British Painting, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, January–June 1938 (64, as ‘The Seducer (After Sir John Gilbert, R.A.)’, £150).

1990

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, London, June–November 1990 (not in exhibition catalogue, exhibited London only from August onwards).

References

1930

T.W. Earp, ‘The Work of Richard Sickert, A.R.A.’, Apollo, 11 April 1930, p.296, reproduced.

1930

‘“Modern Conversation Pieces”: Sickert’s Victorian Inspirations’, Sketch, 5 March 1930, reproduced.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London 1973, pp.178, 385, no.426, reproduced fig.296.

1977

Wendy Baron, Miss Ethel Sands and her Circle, London 1977, p.184.

1981

Richard Morphet, ‘Late Sickert, then and now’, in Late Sickert: Paintings 1927 to 1942, exhibition catalogue, Hayward Gallery, London 1981, pp.8–21.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.596.

Technique and condition

This oil sketch is painted on a commercially prepared canvas purchased from the artists’ colourmen L. Cornelissen & Son. The linen cloth has very coarse and open plain weave and has been prepared with a little glue size and a dense opaque white primer composed of lead white mixed with chalk and zinc white. The primer extends to the cut edges and retains the strong weave texture. The canvas appears to have been re-stretched to improve the tension, possibly by the artist, but more likely later.

Sickert painted an apparently simple linear drawing onto the white ground using thinned black oil paint and a stiff brush. It has some of the consistency of ink but is much thicker and was more viscous when wet. There is no sign of any initial pencil drawing and this would be inconsistent with the confidence and fluidity of the caricature. The black drawing is highly stylised and spontaneous but is reworked in a few areas, such as the tablecloth, the legs and the feet of the figures. On closer examination it appears to have a more tentative and leaner line underneath which is visible in many areas. These black lines are drier and only impact on the canvas-weave tops, perhaps by keeping the paint on the brush without solvent. This is probably Sickert’s first stage of drawing. In a later series of lectures he delivered at the Margate School of Art he outlined the importance of these early stages of working:

When you are drawing you must be clear that you do three things and the first thing you must do is to get your tentative line. The first thing you must remember about your tentative line is that it is not a thing that has to be done and then washed out. That is the English view of everything. People always apologise for such things ... You must leave your tentative line and you must leave it – it must be there when you have finished.1

The artist has blocked in between the lines with patches of paint to depict areas of light and shade and to indicate the local colour. There is a wide range of colours, though none particularly strong: cool pink, green, pale blue, dull orange, dull yellows, greys, browns and darker pinks. The background yellow has two separate applications of different tones, indicating that there may have been two separate stages of painting, although drying time may not have been necessary, except for the yellow, since in general the paint was applied so sparingly. The coloured paint is applied by brush, prepared on a palette with little subsequent dwelling or mixing on the canvas. The application leaves some soft impasto. Sickert may have added more medium or solvent to his paint to improve its flow and the oil ground is not particularly absorbent. Like the black paint, areas of colour on the floor, for example, are applied dryly across the canvas texture creating a broken line. The drawn black lines remain visible to dominate the composition, presumably in imitation of the original work by John Gilbert, and some are applied on top of later paint. There is a thin overall glossy varnish which has been crudely brushed on, leaving runs on the bottom tacking edge; it is probably not original.

Stephen Hackney

November 2004

Notes

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', November 2004, in Robert Upstone, ‘The Seducer c.1929–30 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

This picture is from the series Walter Sickert made in the late 1920s and early 1930s which he described as ‘Echoes’. They were mainly copied from Victorian illustrations which he found in old editions of the Illustrated London News and similar publications; he made in all around a hundred such works. Sickert took The Seducer from a design by Sir John Gilbert (1818–1897), which is acknowledged in the inscription. The published source for the design remains unidentified. Sickert made more Echoes after Gilbert than after anyone else. The artist William Rothenstein wrote of the Echoes:

Walter’s latest works are a witty commentary on the nineteenth century, on its charm and absurdities, on its art at once so enchanting and so blatant. His mind remains ever alert to see the possibility most artists neglect.1

When Sickert had an exhibition at the Savile Gallery in March 1930 that included eight Echoes, among them The Seducer, responses were mixed. His friend Ethel Sands reported that there were ‘one or two good ones but mostly things from old caricatures which are desperately silly’.2 Similarly, the Bloomsbury artist Vanessa Bell judged them ‘idiotic’ and claimed they fell ‘between so many stools they hardly exist’.3 But in Apollo, the critic T.W. Earp praised them as

brilliant ... their line, necessarily less cramped than that of the original models, flows beautifully. It has the ease and personality of a signature. The colour is pushed to its most excessive limit and [is] admirably harmonious.4

Sir Osbert Sitwell, who knew Sickert well, described the genesis of the Echoes, writing how the artist’s

long hours spent in staring at prints and engravings and old newspapers, were beginning to bear fruit. In 1927 he began to paint his grand series Echoes, as they were called. The first of them was taken from a scene on the lid of a mid-nineteenth-century pomade-box, and they were all of this kind, adaptions, transposed to a larger scale, of works by older artists. But, because of this, and because also Sickert had reverted to the ancient studio practice of having assistants helping to prepare the ground, and because, still more, of his ineradicable sense of humour, the virtues and importance of these works have been minimised and in some quarters dismissed. Nor was it entirely the fault of the critical that this was so, for Sickert could never restrain his wit. One day, for instance, in the thirties, my brother [Sacheverell] met him at the Leicester Galleries, where an exhibition of his later work of this kind was in progress. Sickert turned round, after looking at a picture, and remarked to my brother:

‘It’s such a good arrangement; Cruikshank and Gilbert do all the work, and I get all the money!’5

‘It’s such a good arrangement; Cruikshank and Gilbert do all the work, and I get all the money!’5

John Gilbert was born in Blackheath and studied under George Lance (1802–1864), who had been a pupil of Benjamin Robert Haydon (1786–1846). As a young man Sickert knew Gilbert, and revered him both as a great artist and as a link with the past. In a lecture given at the Margate School of Art on 26 October 1934, taken down in shorthand by one of the students, he recalled his first meeting with Gilbert:

I was sent to him (a great piece of luck) as a draughtsman, as I was sent to see all sorts of people (I made drawings of Curzon, Labouchere and the Maharajah of Bhavnagar, a very mixed bag). I was sent down to see Gilbert in his beautiful house in Blackheath. He was then a venerable old man. He received me most amiably. While there, with the indiscretion of my then age, I began to preach to him about different principles and things ... I said I thought it nonsense for anyone to paint or draw from nature. In saying that then, I said something which I now regard to be more certainly true than I could have been expected to have appreciated at that early age. He replied laughingly, ‘Well, I am very glad to hear a young man say that, because I believe that too.’ He went on to say, ‘I may say I myself like to have my comforts about me’ ... a good reason, because it is not as easy to do something as well in an east wind and wet boots as before your own fire in your study.6

Sickert was sent to see Gilbert by the Pall Mall Budget in 1893, for which, as he related, he made a number of portrait illustrations. His drawing of Gilbert appeared in the magazine on 13 April 1893.7

When the exhibition of Echoes was held at the Leicester Galleries in May 1931, Sickert included an appendix in the catalogue in which he described the artists from whom he had taken designs. Of Gilbert he wrote:

He was best known for his illustrations of Shakespeare. It is probable he will be ultimately remembered by his smaller cuts in the London Journal and other periodicals, where he was master of romantic and melodramatic subjects, and could move more freely in ground that had not been stereotyped by the theatre. His pencil shone with equal facility in low-life, colonial subjects, and in dazzling saloons of the aristocracy.8

When Leicester Art Gallery purchased Sickert’s Echo, The Bart and the Bums,9 in 1931, Sickert wrote to them explaining something of this picture and the series in general. The letter further reveals his feelings about Gilbert, and his motivation in making the Echoes. After recalling his commission to draw Gilbert, Sickert wrote:

I little thought I should be the humble instrument of drawing public attention to the interest of a rigorous and ‘populacier’ composition by that great artist. The drawing illustrated a story in the London Journal, the literary merit of which story is not sufficient to attract permanent interest in the illustrations.

The design would have remained buried forever if I had not felt inspired to translate it into a painting. Claiming thereby the same liberty as Pope or Butcher, Lang or Schlegel claim with Homer, Virgil with Homer, Fitzgerald in the Omar Khayyam, &c. I confess also a desire to do a little propaganda by sending the younger painters to rifle the wealth of English sources of inspiration.

Thousands who will see this low-comedy design would not have seen it but for

John Gilbert who inv. et del.

Gorway who sculpst.

me who have had the temerity to trace in paint the admired monogram JG.10

John Gilbert who inv. et del.

Gorway who sculpst.

me who have had the temerity to trace in paint the admired monogram JG.10

The important collector John Blyth was an early owner of The Seducer. In his first thirty years of collecting, Blyth bought only the work of Scottish artists, but in the 1940s and 1950s he turned his attention to English art, in particular the Camden Town Group. He owned pictures by Spencer Gore, Harold Gilman and a total of twenty-four works by Sickert. Blyth played an active role at Kirkcaldy Art Gallery in Fife, having up to half his large collection on loan there at any one time as well as chairing the art committee. Following his death, 128 works from his collection were purchased for Kirkcaldy.11 Kirkcaldy Art Gallery never exhibited The Seducer and according to their records it appears to have remained in Blyth’s drawing room at Wilby House, Kirkcaldy.

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

Ethel Sands, letter to Nan Hudson, 1930; quoted in Wendy Baron, Miss Ethel Sands and her Circle, London 1977, p.184.

T.W. Earp, ‘Richard Sickert: English Echoes’, Apollo, 13 June 1931; quoted in Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, London 2005, p.576.

Osbert Sitwell (ed.), A Free House! or the Artist as Craftsman being the Writings of Walter Richard Sickert, London 1947, p.liii.

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.57.22; reproduced in Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, fig.211.

Walter Sickert, ‘The Sources’, in English Echoes. A Series of Paintings by Richard Sickert, A.R.A., exhibition catalogue, Savile Gallery, London 1931.

Related biographies

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘The Seducer c.1929–30 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www