The Camden Town Group and Early Twentieth-Century Ruralism

Ysanne Holt

In the early 1900s the relationship between town and country underwent a period of dramatic change, as the growth of suburbs and transport systems allowed people to escape from London to the countryside. Ysanne Holt considers contemporary attitudes towards the rural and the image of the countryside shown in Camden Town paintings.

The title, the Camden Town Group, generally conjures associations of a realist or truthful style of painting and a range of themes associated with everyday life and social class in the metropolis, if not specifically the north London suburb from which the painters took their title in 1911. A large proportion of paintings by members of the group shown in their three exhibitions at the Carfax Gallery were, however, of landscapes and rural scenes or else of glimpses of nature to be perceived within the city. It is interesting therefore to consider these Camden Town Group images of rural, semi-rural or of urban scenes of nature within a transition from late Victorian to Edwardian cultures of ruralism, and in relation to representations by other artists and exhibiting societies and other views of the countryside being circulated in London in the years leading up to the Great War.

While for many throughout the nineteenth century the city was both imagined and experienced as a site of progress and opportunity, it is more generally the case – as Raymond Williams has demonstrated – that the country and the city were more commonly perceived throughout the period as polarities of good and bad, order and disorder, health and disease.1 From the late 1880s into the early years of the twentieth century a series of characteristic laments – as typified by Liberal MP C.F.G. Masterman’s The Heart of Empire: Discussion of Modern City Life (1901), From the Abyss (1902) and The Condition of England (1909) – expressed anxieties about the ‘problems’ of city life, in which the inner city is an over-crowded, unhealthy site of moral and physical degeneracy and decay. Such a view recalls Victorian concerns about generations of ‘street-bred’ children and wider fears of an underclass – rekindled for many perhaps by Walter Sickert’s lurid representation of lives lived out amidst degrees of poverty and desperation. Concerns continued about restless workers, increasingly prone to strikes and union unrest; and about the uneducated, unemployed and unemployable, morally and physically unfit. These were all social and economic problems to be addressed by a reformist Liberal government in the years before 1914. More generally, newspapers and periodicals in the Edwardian era were consistently underlining, and at times fomenting, unease and resentment among classes who were increasingly segregated in distinct locations within the capital. This was a period of sustained growth in the inner suburbs, areas that were often, although not exclusively, perceived and represented by writers and commentators in terms of stifling monotony. Appearing in 1906, H.G. Wells’s Tono-Bungay delivered a typically bleak account of suburbia: ‘Endless streets of undistinguished houses, undistinguished industries, shabby families, second-rate shops, inexplicable people who in a once fashionable phrase, do not “exist”.’2

In this context we might comprehend Georgian poet Edward Thomas’s 1913 account of ‘the modern, sad passion for nature’ as, fundamentally, a nostalgic yearning for traditional ways of being, for ordered structures of class and society, for a sense of wholeness and a ‘felt-life’.3 This typically conflated fantasies of rural virtue with notions of a vital and more vigorous rural stock; healthy children bred in country villages and sturdy clean-limbed labourers on the land, despite clear indications to the contrary and continual processes of rural depopulation following the depression of British agriculture in the late 1880s and 1890s. The move to the city was for many rural inhabitants a move for work and an escape from the relentless tedium of life on the land – a fact acknowledged in numerous turn of the century accounts of rural decay and decline, but not loudly enough to quell ingrained urban fantasies. Underlying these yearnings were anxieties too about the gradual decline of Empire, the constant pace of change, and antipathies towards modernism and wider European and transatlantic influence on culture and society more broadly. The English countryside seemed an all the more precious commodity.

Throughout the Edwardian era a vein of melancholic nostalgia, fuelled by negative responses to urban life, underpins accounts of Englishness as a dominant national, cultural identity perennially rooted in the countryside – most particularly the picturesque villages, cultivated fields and rolling hills of the south – and predicated on appeals for tradition and continuity. But this was not the only response. The culture of ruralism was more changeable and unfixed in the Edwardian era than has been recognised. Perceptions of rural life were increasingly adaptive to diverse tendencies and communities and were, for many, less defined by deep lament and backward longings as the era progressed. Despite the persistent tone of much ruralist literature, an impulse ‘back to the land’ and for a ‘simple life’ did not necessarily imply a rejection of modern civilisation. That observation certainly applies to paintings of rural subjects by key members of the Camden Town Group, in contrast to works by many artists at institutions like the Royal Academy and the New English Art Club in the years leading up to the war.

The first years of the century were characterised by rapid social and technological transformation and ever more widely circulating forms of visual communication: colourful posters, newsreel and more accessible and widespread photography following the advent in the late 1880s of Kodak cameras and rolled film. The latter, of course, gave rise to photography shops in the city, to numerous photographic societies and to the developing popularity of tourist photography and guidebooks.4 Most important in this respect too was greater access to transport – from the appearance of the first electric tube line in 1890 to the growing number of suburban train lines before 1914.

Make Motoring Delightful by Fitting your Car with Dunlop Tyres and Detachable Wire Wheels 1912

Country Life Picture Library

Photo © Country Life Picture Library

Fig.1

Make Motoring Delightful by Fitting your Car with Dunlop Tyres and Detachable Wire Wheels 1912

Country Life Picture Library

Photo © Country Life Picture Library

John Henry Lloyd

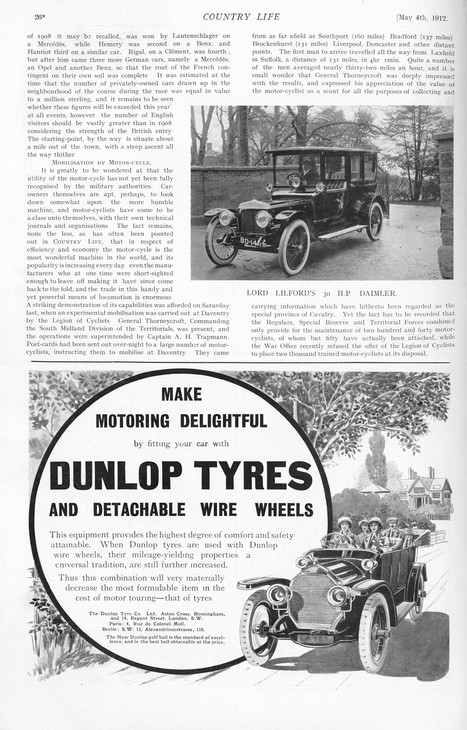

Too Much of a Good Thing 1910

Poster

1016 x 635 mm

London Transport Museum

Photo © TfL from the collection of London Transport Museum

Fig.2

John Henry Lloyd

Too Much of a Good Thing 1910

London Transport Museum

Photo © TfL from the collection of London Transport Museum

It is within this context of a shift away from an overtly sentimental and retrospective pastoralism towards a more modern representation of landscape and a potential intermingling of town and country that the paintings of Spencer Gore can be perceived. As a student at the Slade between 1896–9, Gore’s most immediate influence was Sickert’s exact contemporary, Professor of Painting, Philip Wilson Steer. Steer had been a founding member of the New English Art Club in 1886 and an exhibitor at Sickert’s London Impressionists exhibition in 1889. Unlike Sickert, however, Steer was not drawn to low-life urban subjects. He was more typically a painter of landscape and had achieved notoriety in the late 1880s for his daringly impressionist, at times neo-impressionist handling of sea and beach scenes, revealing an advanced knowledge of Claude Monet and even Georges Seurat at a time when conservative British tastes struggled to accommodate those artists (Tate N05766, fig.3). By the later 1890s, however, Steer was reworking the English landscape traditions of the earlier nineteenth century in oils and watercolours and was increasingly venerated during a wave of cultural chauvinism in the 1890s as the foremost successor to John Constable, with works such as Bird-nesting, Ludlow 1898 (Tate N04955, fig.4). A taste for tree-framed compositions in some of Gore’s landscapes painted in Yorkshire demonstrate signs of Steer’s influence on the young artist, as in The Milldam, Brandsby, Yorkshire 1907 (private collection).9

Philip Wilson Steer 1860–1942

Figures on the Beach, Walberswick circa 1888–9

Oil on canvas

support: 610 x 610 mm; frame: 780 x 790 x 110 mm

Tate N05766

Purchased 1947

© Tate

Fig.3

Philip Wilson Steer

Figures on the Beach, Walberswick circa 1888–9

Tate N05766

© Tate

Philip Wilson Steer 1860–1942

Bird-nesting, Ludlow 1898

Oil on canvas

support: 571 x 927 mm

Tate N04955

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1937

© Tate

Fig.4

Philip Wilson Steer

Bird-nesting, Ludlow 1898

Tate N04955

© Tate

A more enduring influence for Gore, however, was to be the broken colour and handling of the French artist Lucien Pissarro, whose rural and semi-rural landscapes dating from the 1890s Gore was able to see at New English Art Club exhibitions from 1904 (Tate N04747, fig.5). By late 1907, Gore was well acquainted with Lucien at Fitzroy Street Group meetings and signs of the latter’s impact are clearly visible in the modified divisionism of Gore’s paintings of the garden and landscape around his mother’s house at Hertingfordbury, as, for example, in The Garden, Garth House 1908 (fig.6), which bears similarities to paintings by Lucien of his father Camille’s garden at Eragny in France and of his own gardens in England. Lucien was also to be of long-standing importance to the works of later Camden Town Group secretary James Bolivar Manson, who praised his ‘faculty of finding in the beauty of everyday life, material for the exercise of [his] art ... a characteristic, from the beginning of the Impressionist school’.10 Manson, like Gore, emulated Lucien’s handling in subjects like Lilian in Miss Odell’s Garden c.1910 (private collection).11

Lucien Pissarro 1863–1944

April, Epping 1894

Oil paint on canvas

support: 603 x 730 mm

Tate N04747

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1934

© Tate

Fig.5

Lucien Pissarro

April, Epping 1894

Tate N04747

© Tate

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Garden, Garth House 1908

Oil paint on canvas

483 x 584 mm

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Photo © National Museums Liverpool

Fig.6

Spencer Gore

The Garden, Garth House 1908

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Photo © National Museums Liverpool

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Mornington Crescent 1911

Oil paint on canvas

support: 635 x 762 mm; frame: 839 x 966 x 62 mm

Tate N05099

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

Fig.7

Spencer Gore

Mornington Crescent 1911

Tate N05099

Gore, and equally both William Ratcliffe and Harold Gilman in their paintings of nearby Clarence Gardens of 1912, resist categorisations of the inner suburbs as had emerged in Masterman and most notably in T.W.H. Crosland’s The Suburbans (1905).13 Camden Town Group painters very frequently sought out more orderly and tranquil London locations. They avoided either bustling or sordid and shabby scenes, underlining fragments of nature, tree-lined squares, corners of parks and spots of green and point to a more optimistic, pleasurable view of a coexistence of town and country. This is a more modern vision, quite in tune with contemporary social developments and aspirations. In this respect Camden Town Group paintings are, very often, markedly different from a variety of other Edwardian images of nature.

If, as we have seen, by 1912 the capital was full of images of the countryside in Underground and railway station posters, in newspaper and periodical photographs, and in the lithographic illustrations to the proliferating rural guidebooks of the period, it was also full of an array of different types of landscape paintings to be seen in numerous and diverse sites of display: commercial galleries, art societies and institutions. Partisanship between venues and associations between landscape types typically seen at those institutions were much discussed, with, by 1912, a very clear sense that distinctions between the works shown at one-time rival institutions the New English Art Club and the Royal Academy were now no more. As the critic C.H. Collins Baker noted in May 1912:

For some weeks the tubes have urged us to book to Dover Street for the Royal Academy, indicating that the number of visitors to the show will be lucrative from a traffic standpoint ... Obviously the exhibition ... is a conspicuous social and business concern ... we encourage people who have the minds of sentimental schoolgirls (or boys) to bore us with their trivial ideas ... it is almost fatuous to make this perambulation, every year, among things we know by heart.14

Sir Alfred East 1844–1913

Golden Autumn ?1904

Oil on canvas

support: 1225 x 1530 mm

Tate N04917

Presented by Mrs Mildred Donald 1938

Fig.8

Sir Alfred East

Golden Autumn ?1904

Tate N04917

Sir George Clausen 1852–1944

The Gleaners Returning 1908

Oil on canvas

support: 838 x 660 mm

Tate N02259

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1908

© Tate

Fig.9

Sir George Clausen

The Gleaners Returning 1908

Tate N02259

© Tate

East and Clausen were frequently illustrated in contemporary art journals, like the influential and widely circulated Studio magazine, which in its reviews and studio-talk sections directed London gallery-goers around the bewildering number of galleries and exhibitions. The Studio itself was a powerful proponent of ruralism from its inception in 1893, frequently containing lengthy biographies of landscape painters, notes on artists’ haunts and sketching grounds and photographs of, for example, ‘Artistic Arrangements of English Gardens’, book reviews on ruralist subjects like Mr Batsford’s The Essentials of a Country House, and accounts of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society. Its 1910–12 gallery round-ups are full of reference to landscape and rural subject artists like Steer, Walter Russell and Edward Stott who had come to prominence in the 1890s. Indeed, it is easy to forget from a survey of that magazine’s pages with its accounts of ‘noble pastorals’16 (a reference to Arnesby Brown’s ever-popular scenes of contentedly grazing cattle) that these are the years of the introduction of post-impressionism to the London galleries and the formation of the Fitzroy Street and Camden Town groups – although a short review of the group’s third Carfax show in December 1912 did admire ‘Mr J.B. Manson’s virility and sometimes charm and Mr Spencer Gore’s unconscious poetry in landscape [over] the pattern making pure and simple of Mr Ginner and Mr Drummond’.17

Other magazines like Country Life had, by 1912, also begun to refer to contemporary artists in their pages. Among advertisements for motorcars, contractors for ‘Bungalow and Cottage residences’, for Rexine fake leather sofas and Heal’s bedroom furniture appear reviews of Lucy Kemp-Welch and Alfred Munnings’s exhibition Horses at the Academy. All of which demonstrates a familiar disjunction within the period – a deep conservatism in its tastes in art, and modernity in the world of advertising and material consumption – here in a magazine which is much more metropolitan-oriented than we might expect.

After 1909 Gore, Charles Ginner and Robert Bevan made several painting trips to a West Country farm, Applehayes, in the Blackdown Hills near Clayhidon in Devon. Applehayes was a 300-acre estate acquired in 1909 by Harold Bertram Harrison, an older student contemporary with Gore at the Slade, who erected artists’ studios among his extensive farm buildings. The adjacent county of Cornwall had long been an artists’ haunt and its fishing villages the site of several artists’ colonies since the 1880s. Sickert and Whistler had painted seascapes at St Ives in 1882 and, for example, the Manson painting of his wife Lilian referred to earlier was painted in a holiday cottage garden in Padstow c.1910. Cornwall had increasingly become a popular tourists’ destination too, but Devon – aside from its seaside resorts – was less visited by artists and tourists, hence perhaps expectations of the unspoilt and remote.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Applehayes c.1909–10

Oil paint on canvas

511 x 611 mm

Ulster Museum, Belfast

Photo © National Museums Northern Ireland

Fig.10

Spencer Gore

Applehayes c.1909–10

Ulster Museum, Belfast

Photo © National Museums Northern Ireland

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Landscape with Farmhouses 1912–13

Oil paint on canvas

512 x 687 mm

Manchester City Galleries

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Manchester City Galleries

Fig.11

Charles Ginner

Landscape with Farmhouses 1912–13

Manchester City Galleries

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Manchester City Galleries

Gore’s plein-air paintings of the surrounding landscape demonstrate a marked shift from the impressionism of the Pissarros, as seen in Applehayes c.1909–10 (fig.10), towards a greater emphasis on structure and outline derived from Paul Cézanne. The physical character of the landscape encouraged such a transition in technique. For Bevan and Ginner the influence of Paul Gauguin’s cloisonnisme, as shown, for example, in Ginner’s Landscape with Farmhouses 1912–13 (fig.11), is especially marked and, for the latter, this was combined with the decorative impasto from van Gogh. Examples of Cézanne’s, van Gogh’s and Gauguin’s works were to be seen, controversially, in London exhibitions from 1910, but the Camden Town Group artists were already familiar with their paintings from earlier visits to France. Gore, for instance, had visited the Cézanne exhibition at Durand-Ruel’s gallery in Paris in 1905 and saw Gauguin’s works at the 1906 Salon d’Automne in the company of Sickert. Bevan had met Gauguin at Pont-Aven in Brittany on a visit to the artists’ colony in 1894. Stylistic influence from artists associated with ‘primitive’ or isolated landscapes in France – in the Midi or off the beaten track in Brittany – seems especially appropriate in the context of this ancient Devon landscape. Nonetheless, with their generally strong emphasis on rhythmic pattern in the observation of orderly stone walls or hedgerows and long-standing but well-maintained farm buildings, the overall effect of many of these Camden Town painters’ depictions of the Devon countryside is not actually of a wild and untamed landscape, but of a secure and cultivated one with, as the art historian Sam Smiles has noted, some connection through to an earlier nineteenth-century picturesque landscape aesthetic.18

These visits were very much temporary painting vacations for Gore and Ginner. Long solitary periods of immersion in an isolated natural environment was to be a feature only of Bevan’s practice as he spent the First World War years and afterwards in sustained periods painting in nearby Bolham Valley. The concept of ‘going away’ – but always predicated on the ‘coming back’ in time for key London exhibitions – relates best to the practice of two ex-Slade students and short-term members of the Camden Town Group, J.D. Innes and Augustus John. In the spirit of dissipated bohemians infatuated with the ideals of unfettered gypsy life, these ‘artist travellers’ spent time before 1914 on prolonged painting trips to remote locations in Wales, Ireland and the south of France. They were in flight from the city, for which John at least felt much distaste, and in search of more elemental, uncultivated scenery than the largely Home Counties ‘picnic’ or ‘august site’ landscapes – as Laurence Binyon and Sickert respectively described works on display at New English and Royal Academy shows and in West End galleries.19

James Dickson Innes 1887–1914

Arenig, Sunny Evening circa 1911–12

Oil on wood

support: 229 x 324 mm

Tate N05367

Purchased 1942

Fig.12

James Dickson Innes

Arenig, Sunny Evening circa 1911–12

Tate N05367

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Letchworth 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 509 x 612 mm; frame: 755 x 650 x 65 mm

Tate N04675

Purchased 1933

Fig.13

Spencer Gore

Letchworth 1912

Tate N04675

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Fig Tree c.1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 635 x 760 mm

Tate T00028

Bequeathed by J.W. Freshfield 1955

Fig.14

Spencer Gore

The Fig Tree c.1912

Tate T00028

That final show displayed a large number of rural scenes and landscapes, including Gore’s vivid study of an enclosed area of woodland by a stream, Letchworth Common, which the art historian Wendy Baron has noted may be the Tate’s Letchworth 1912 (Tate N04675, fig.13).22 The Fig Tree 1912 (Tate T00028, fig.14) – a study of lush blue-green foliage in a vertiginous view down into the gardens of Houghton Place seen from Gore’s first-floor window – was hung in the same exhibition. Perspective in both works is very different; the Letchworth picture is painted en plein-air using broad sweeps of colour and from an intimate ground-level position, allowing a greater sense of the artist’s involvement in the natural environment than the distanced observation in The Fig Tree. But the rich colour, broad handling and dense composition are similar and give a clear sense of the artist’s developing direction. Gilman and Ratcliffe both lived in Letchworth at this period and Gore and his young family stayed in Gilman’s house in the summer of 1912. These artists’ attraction to the First Garden City, thirty-four miles outside London, firmly underpins the particular form of Edwardian ruralism this essay describes.

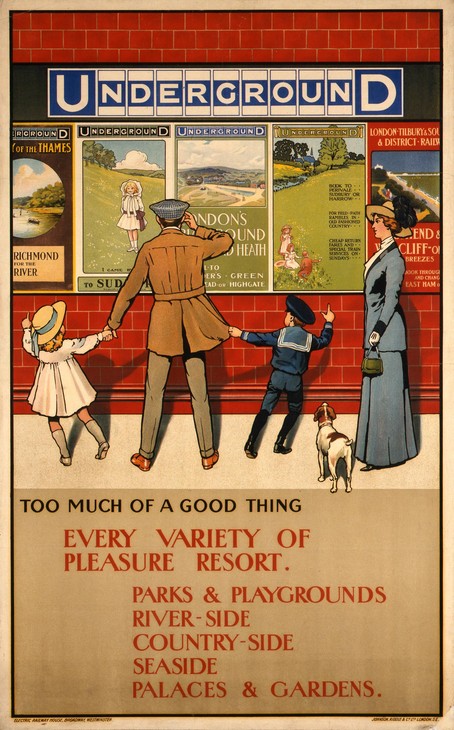

Ebenezer Howard 1850–1928

Three Magnets diagram, showing the Town, Country and Town-Country c.1898

First Garden City Heritage Museum

Photo © First Garden City Heritage Museum

Fig.15

Ebenezer Howard

Three Magnets diagram, showing the Town, Country and Town-Country c.1898

First Garden City Heritage Museum

Photo © First Garden City Heritage Museum

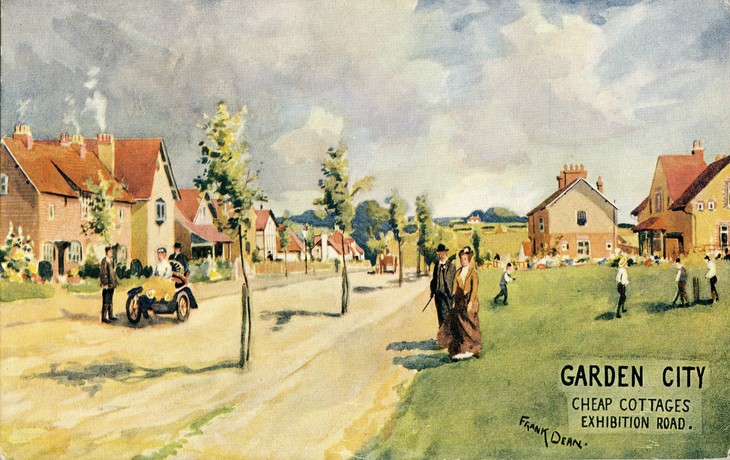

Frank Dean 1865–1907

Garden City, Cheap Cottages Exhibition Road c.1905

Postcard

First Garden City Heritage Museum

Photo © First Garden City Heritage Museum

Fig.16

Frank Dean

Garden City, Cheap Cottages Exhibition Road c.1905

First Garden City Heritage Museum

Photo © First Garden City Heritage Museum

Ebenezer Howard’s 1903 utopian vision, Garden Cities of Tomorrow (fig.15), intended to bring together the advantages of town and country and was, fundamentally and in practice, a re-housing scheme, designed to remove Londoners from cramped and unsanitary inner-city conditions into the beneficial atmosphere of space, healthy fresh air and access to surrounding green fields and woodland – as depicted in Gore’s painting. Competitions for small cottage designs, frequently reported upon by the Studio, emphasised the importance of simplicity and sound construction, primarily interpreted in a vernacular style and underlining the extent to which Garden Cities were envisaged as an ideal compromise between tradition and modernity (figs.16 and 17). Their impact and the general drift to the outer suburbs and to the Home Counties was clear to see and Letchworth’s population, for example, rose from 400 in 1903 to 6,000 by 1910. Country Life reported in its 1912 survey ‘The Future of London’:

Only a few years ago it seemed that the growth of the ‘great wen’, as Cobbett called the metropolis, was a thing unpreventable. For hundreds of years it had steadily continued swallowing up villages, covering streams, forming crowded tenements ... Now apparently the tide has turned ... the number of empty houses is continually increasing ... families are leaving the central boroughs at a rate of about thirteen thousand per annum, ... it by no means indicates any falling off in the prosperity of London. It is due, as all men know, to the modern passion for country life and the facilities afforded for enjoying it by the increased methods of transport ... When the tube railways were started it was considered doubtful whether they would be remunerative, so few was the number of passengers, but now in the morning and in the evening they are overloaded to a degree that is certainly uncomfortable and might be dangerous ... At first the egress from the City practically stopped at the suburbs, then it reached out for a mile or two beyond them, and now the country within a radius of thirty or thirty five miles is drained of its population in the morning and refilled in the evening. Instead of suburbs we have growing cities that have become the adjuncts of London, places like Letchworth and Golder’s Green for example. The overall effect is not in the slightest degree to be deplored. Those who take up their residence in the country adjacent to the metropolis are invigorated by the fresh air, even though they do little more than go home to sleep. Business is transacted with all the greater spirit and vigour for the change. The movement and excitement of the journey are in themselves beneficial.23

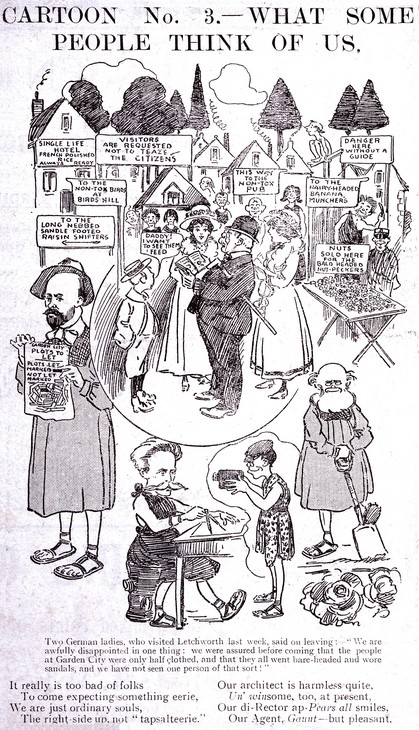

Louis Weirter 1873–1932

What Some People Think Of Us 1909

First Garden City Heritage Museum

Photo © First Garden City Heritage Museum

Fig.18

Louis Weirter

What Some People Think Of Us 1909

First Garden City Heritage Museum

Photo © First Garden City Heritage Museum

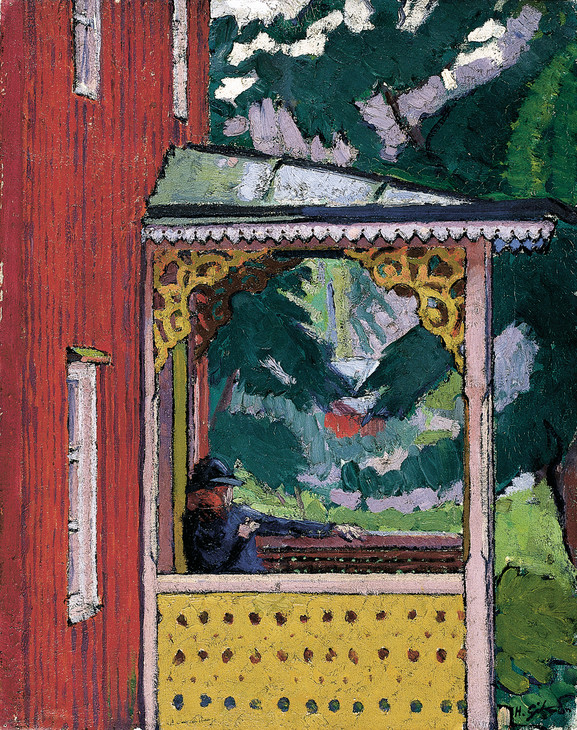

Of interest here too are contemporary Garden City artistic links to Scandinavia. Ratcliffe spent time painting in Scandinavia and Gilman’s neighbour in Wilbury Road was Signe Bergström, Swedish wife of Stanley Parker, the brother of one of the Letchworth architects. Gilman himself visited Sweden in 1912 and the following year travelled to Norway. On both occasions he produced brilliantly coloured and simplified landscapes and studies of field workers at a time when his work was demonstrating the influence of van Gogh. Gilman showed three Swedish pictures at the final Camden Town Group exhibition that year, including The Reapers, Sweden (Johannesburg Art Gallery).25 A particular mix of Scandinavian and British aesthetic tendencies emerges in this period, intermingling with discourses of health, sunlight and the outdoors. A Scandinavian taste for clean, uncluttered lines and simple proportions also contributed a modern and cosmopolitan influence to late manifestations of the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain, as can be seen in Gilman’s Verandah, Sweden 1912 (fig.19), and Scandinavian design, crafts and architecture were frequently featured in the Studio magazine throughout these years.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

The Verandah, Sweden 1912

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 406 mm

The Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Gift of The Second Beaverbrook Foundation

Photo © The Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, NB

Fig.19

Harold Gilman

The Verandah, Sweden 1912

The Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Gift of The Second Beaverbrook Foundation

Photo © The Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, NB

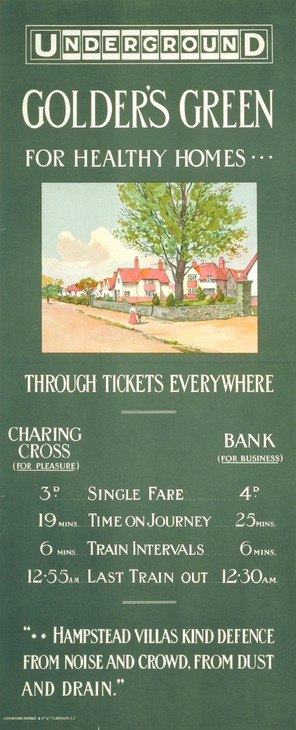

Golder's Green for Healthy Homes 1910

Panel poster

524 x 217 mm

London Transport Museum

Photo © TfL from the collection of London Transport Museum

Fig.20

Golder's Green for Healthy Homes 1910

London Transport Museum

Photo © TfL from the collection of London Transport Museum

In its continual campaign to educate its pre-war expanding readership on matters of taste, the Studio increasingly included articles on the new advancements in poster design referred to earlier. In fact there is a noticeable lag between the modern character of the design and architecture discussed in the magazine and the much more conservative nature of the paintings, landscapes or others reproduced in its pages – a situation not really adjusted until after the First World War. Modernism was more immediately palatable in the form of architecture, design and decoration. By 1910, however, the modern posters which the Studio discussed were already characterised by a radical simplification of colour and form.26 As Curator at the London Transport Museum David Bownes has demonstrated, from this point posters were increasingly ‘selling an aspirational vision of suburban life’ in a departure from simply encouraging Londoners to take days out and holidays in the country. Especially talented emerging poster designers, like the once architectural draughtsman Fred Taylor and the landscape artist Walter Spradbery, evolved ‘a visual language for suburban selling’. The 1910 poster Golder’s Green for Healthy Homes (fig.20) is a good example, using, as Bownes points out, ‘an artistic, rather than photographic representation of an idyllic house’ and emphasising, as with Letchworth, a sense of the best of both worlds – fresh air and easy access to the city, with a style of architecture rooted in the Arts and Crafts tradition pioneered by Voysey and Baillie Scott.27

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Letchworth, The Road 1912

Oil paint on canvas

406 x 432 mm

Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery

Photo © Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery (North Hertfordshire Museum Service)

Fig.21

Spencer Gore

Letchworth, The Road 1912

Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery

Photo © Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery (North Hertfordshire Museum Service)

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Cinder Path 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 686 x 787 mm; frame: 815 x 924 x 73 mm

Tate T01960

Purchased 1975

Fig.22

Spencer Gore

The Cinder Path 1912

Tate T01960

Gore’s Letchworth, The Road 1912 (fig.21) perfectly demonstrates the simplification of his forms and the brightening of his palette at this period, resulting in a decorative composition that retains the fundamental character of the scene before him. As a result of this process, as his own critical response to Cézanne, Gauguin and van Gogh at the first of Fry’s post-impressionist exhibitions reveals, the artist might best express ‘the emotional significance which lies in things’.28 It was a quality he observed too in Henri Matisse, André Derain and Auguste Herbin at this period. The process of radical simplification and emphasis on an overall balanced and rhythmic design seen both in The Road and in, for Gore, the large-scale work The Cinder Path 1912 (Tate T01960, fig.22), shown at Fry’s second post-impressionist exhibition, combine to represent a view of the Garden City as harmoniously merging into the countryside in an ideal unity of town and country, of culture and nature. Gore’s Letchworth Station of 1912 (fig.23 and 24), also shown at Fry’s exhibition and illustrated in the catalogue, might actually stand as a perfect illustration to that summer’s Country Life article, extolling – rather like the modern poster – the advantages afforded by the increased methods of transport in bringing nature and the city together, rather than, as P.G. Konody described the painting in the Observer, ‘the silent protest of a lover of the green countryside against the unbending iron and black smoke’.29

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Letchworth Station 1912

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 762 mm

National Railway Museum, York

Photo © National Railway Museum / Science & Society Picture Library

Fig.23

Spencer Gore

Letchworth Station 1912

National Railway Museum, York

Photo © National Railway Museum / Science & Society Picture Library

Letchworth Station c.1907

First Garden City Heritage Museum

Photo © First Garden City Heritage Museum

Fig.24

Letchworth Station c.1907

First Garden City Heritage Museum

Photo © First Garden City Heritage Museum

Konody’s remark recalls Masterman’s lament and those earlier insistent distinctions between the country and the city that were fuelled by nostalgia, resistance to change and modernity, sentiments still much in evidence in Royal Academy and New English exhibitions, despite increasing criticisms. Nevertheless, as certain Camden Town Group painters on their trips to the countryside around 1910–13 were able to observe, it was modernity in the form of new communication and technology that enabled any potentially beneficial, harmonious relationship to develop between town and country, and Gore in particular had achieved the formal means – adapted from European modernism – with which to represent this ideal. There may be, as Edward Thomas had noted, a ‘modern’ ‘passion’ for nature, but it was not necessarily ‘sad’ by 1914.

Notes

On the developing enthusiasm for landscape photography from the 1890s, see, in particular, John Taylor, A Dream of England: Landscape, Photography and the Tourist’s Imagination, Manchester University Press, Manchester and New York 1994.

Cited in Donald Read, Edwardian England, 1901–15, Society and Politics, Harrap & Co., London 1982, p.50.

Catherine Flood, ‘Pictorial Posters in Britain at the Turn of the Twentieth Century’, in David Bownes and Oliver Green (eds.), London Transport Posters: A Century of Art and Design, Lund Humphries, London 2008, p.15. Quote taken from George Sims, Living London, vol.3, Cassell and Company, London 1903, p.216.

See David Buckman, James Boliver Manson: An English Impressionist, 1879–1945, exhibition catalogue, Maltzahn Gallery, London 1973, p.18.

Walter Sickert, ‘A Perfect Modern’, New Age, 9 April 1914, p.718, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, p.355.

For an account of Crosland’s study and for an excellent discussion of early twentieth-century distaste for ‘The Suburbs and the Clerks’, see the chapter with that title in John Carey, The Intellectuals and the Masses: Pride and Prejudice among the Literary Intelligentsia, 1880–1939, Faber and Faber, London 1992.

See Sam Smiles (ed.), Going Modern and Being British: Art, Architecture and Design in Devon c.1910–1960, Intellect Books, Exeter 1998. And see especially Rosalind Billingham, Artists at Applehayes: Camden Town Painters at a West Country Farm, 1909–1924, exhibition catalogue, Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry 1986. Ginner painted at Applehayes in 1912, 1913 and 1914, Gore in 1909, 1910 and 1913 and Bevan in 1912, 1913 and 1915. Slade students Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer and William Roberts also stayed there at different times in the summer of 1911. Between 1916 and 1919 Bevan rented Lytchetts, a cottage a few miles from Applehayes, and purchased another, Marlpits, on nearby Luppitt Common in 1923. See Helena Bonett, ‘‘In these English farms, if anywhere, one might see life steadily and see it whole’: Representations of the Countryside in the Paintings of Robert Bevan and E.M. Forster’s Howards End’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, May 2012, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/helena-bonett-in-these-english-farms-if-anywhere-one-might-see-life-steadily-and-see-it-r1104361 , accessed 27 August 2013.

Binyon was dismissing the ‘picnic landscapes’ at the NEAC which were too engaged in realistic imitation and ‘sensations of well-being’, ‘E Pur Si Mouve’, Saturday Review, 31 December 1910, p.840. Sickert commented on the NEAC’s ‘over-insistence on two motifs. The one the august-site motif, and the other the smartened-up-young-person motif’, in ‘The New English and After’, New Age, 2 June 1910, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.242.

Wendy Baron suggests that John’s choice of small-scale informal studies was an indication of his support of the group, but of not wanting to outshine the less well-known members. See Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Ashgate, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.47.

They were shown at the Chenil Gallery in December 1910. Sickert’s comment came later in his 1914 review of the exhibition Twentieth-Century Art: A Review of Modern Movements at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in the New Age, 28 May 1914, p.83; Robins (ed.) 2000, pp.371–3.

C.S. Bremner, ‘Garden City, The Housing Experiment at Letchworth’, Fortnightly Review, 1 September 1910, pp.512–26.

Paul Rennie, ‘The New Publicity: Design Reform, Commercial Art and Design Education, 1910–1939’, in Bownes and Green (eds.) 2008, p.94.

David Bownes, ‘Selling the Underground Suburbs, 1908–1933’, in Bownes and Green (eds.) 2008, pp.109–13.

Spencer Gore, ‘Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh &c., at the Grafton Galleries’, Art News, 15 December 1910, pp.19–20, in J.B. Bullen (ed.), Post Impressionists in England: The Critical Reception, Routledge, London 1988, pp.140–2.

How to cite

Ysanne Holt, ‘The Camden Town Group and Early Twentieth-Century Ruralism’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www