Henry Moore OM, CH Animal Head 1951

Image 1 of 14

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Animal Head

1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

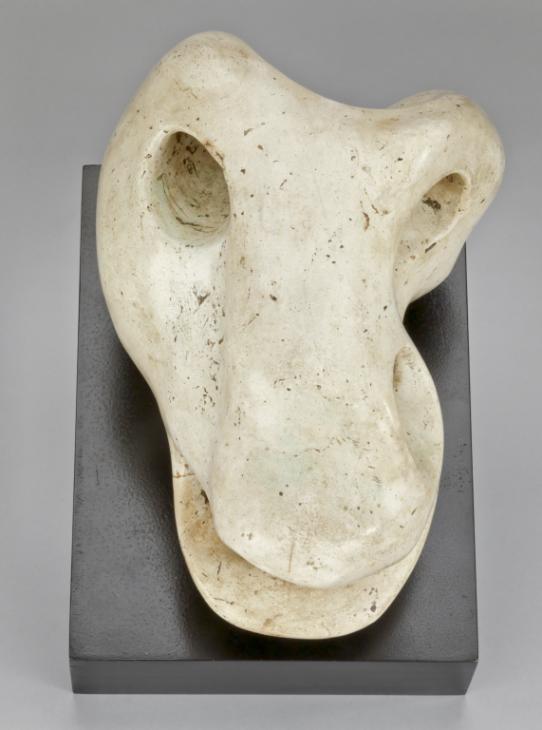

Animal Head is one of Henry Moore’s earliest surviving original plaster sculptures from which bronze versions were cast. The sculpture does not represent a specific animal but draws upon Moore’s interest in the shapes of bones and pebbles and what he called the ‘vitality’ of the natural world.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Animal Head

1951

Plaster on a wood base

270 x 216 x 295 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

T02271

Animal Head

1951

Plaster on a wood base

270 x 216 x 295 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

T02271

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1951

Exhibition of New Bronzes and Drawings by Henry Moore, Leicester Galleries, London, 1951, no.16 (as ‘Head of an Animal’).

1958

Henry Moore, Hatton Gallery, Newcastle, November–December 1958, no.10.

1971

Henry Moore, Musée Rodin, Paris, 1971, no.34.

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972, no.69 (dated 1952).

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et Dessins, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, May–August 1977, no.63.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, April–June 1978, no.85.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983, no number.

1988

Henry Moore, Royal Academy of Arts, London, September–December 1988, no.119.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.38.

2010

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, October 2010–February 2011; Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, March–June 2011; no.131.

References

1959

Erich Neumann, The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, London 1959, p.120 (bronze example reproduced pls.96a–c).

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, p.108 (bronze example reproduced pl.102).

1960

Henry Moore: Sculpture 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Gallery, London 1960 (bronze example reproduced fig.5).

1965

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Sculpture and Drawings 1949–1954, 1955, revised edn, London 1965, no.301 (bronze example reproduced pls.30, 30a).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.189 (bronze example reproduced fig.170).

1964

Seven Decades 1896–1965: Crosscurrents in Modern Art, exhibition catalogue, André Emmerich Gallery, New York 1964 (bronze example reproduced no.258).

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–69, London 1970 (bronze example reproduced fig.413).

1971

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Musée Rodin, Paris 1971, unpaginated (bronze example reproduced fig.34).

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973 (bronze example reproduced fig.69).

1973

Henry J. Seldis, Henry Moore in America, New York 1973 (bronze example reproduced, p.94).

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et Dessins, exhibition catalogue, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris 1977, reproduced pp.111, 167.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Cartwright Hall, Bradford 1978, reproduced fig.85.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.28.

1981

The Tate Gallery: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1978–80, London 1981, p.118–19.

1983

W.J. Strachan, Henry Moore: Animals, London 1983, p.127, reproduced pl.114.

1988

Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, p.230, reproduced no.119.

1986

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore: My Ideas, Inspiration and Life as an Artist, London 1986 (bronze example reproduced fig.28).

2005

Henry Moore y México, exhibition catalogue, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City 2005, reproduced p.68.

2006

Reinhard Rudolph, ‘Animal Head’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works From the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.231–2 (bronze example reproduced p.231).

2010

Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, reproduced no.131.

2011

Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011, reproduced p.58.

Technique and condition

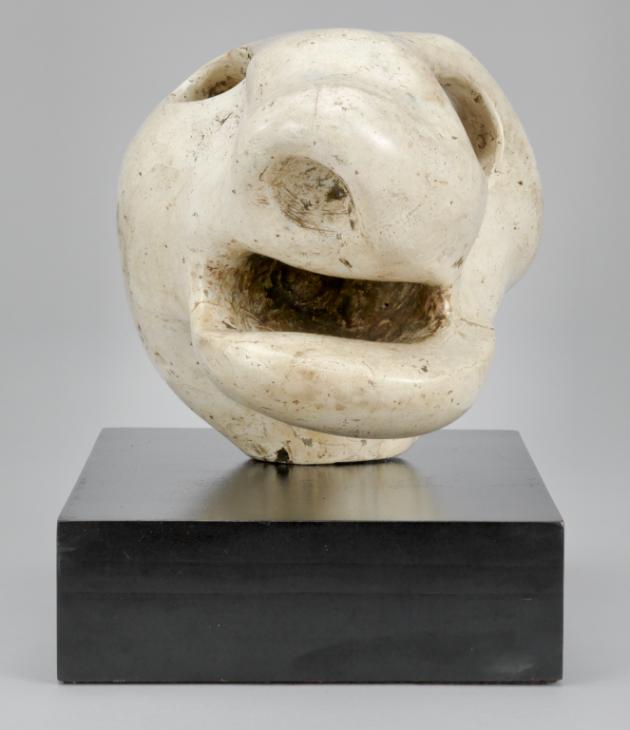

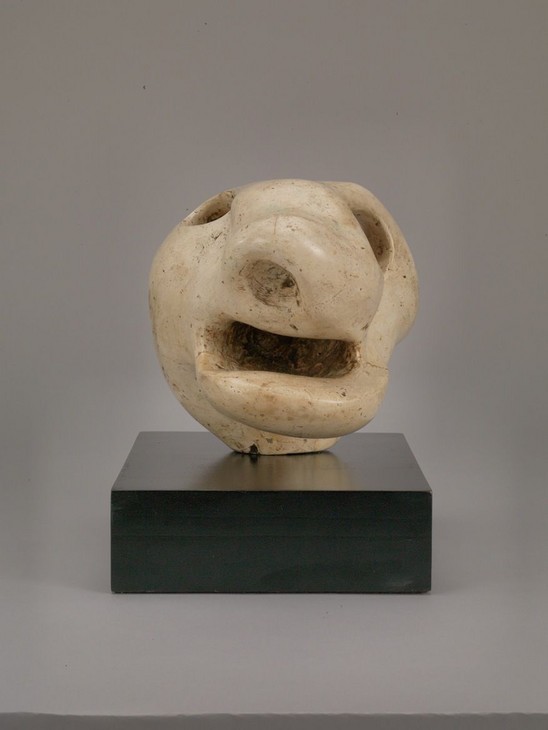

This sculpture of an animal head with a gaping mouth is made of white plaster. The head is mounted on a rectangular wooden base that has been sprayed with a satin black paint.

Detail of mouth of Animal Head 1951

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of mouth of Animal Head 1951

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of green pigment on rear of Animal Head 1951

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of green pigment on rear of Animal Head 1951

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

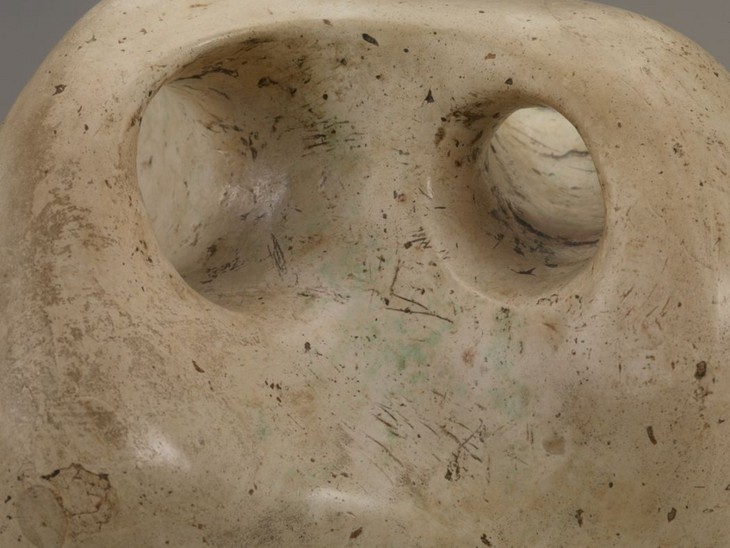

Moore would have made the head by building up successive layers of wet plaster over a supportive armature made of metal or wood. After the plaster had dried and hardened he would have filed the surface and used abrasives to produce the final smooth finish. This process has removed almost all evidence of the tool marks that would originally have been seen on the surface although there are still some visible in the nostril and the hollow of the mouth (fig.1) as well as some linear marks at the back of the head.

The outer surface of the white plaster is largely uncoloured although there is some scattered green staining at the back of the head (fig.2) and under the eye. This plaster model was ultimately used to make a mould so that bronze casts could be made. This would have required the application of a release agent to the plaster surface, often shellac or another varnish, so that the mould could be removed and an undamaged impression of the original obtained. The majority of this release agent has been removed leaving only a slightly yellow tint to the surface, although a thicker brown residue remains inside the mouth with some embedded green fragments (see fig.1). It is not possible to say for certain what the source of the green colour was but it is possible that some bronze dust from the foundry settled on the surface leaving a characteristic green colour. However, curator Anita Feldman has identified that Moore sometimes tinted his plasters ‘with walnut crystals to give the sculptures an organic warmth’.1 It is possible that the green colour on this sculpture was intentional; Feldman also notes that a pale green wash was used ‘to emulate the bronze dust which often accumulated on them over time in the foundries’.2

Detail of lower jaw of Animal Head 1951

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of lower jaw of Animal Head 1951

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

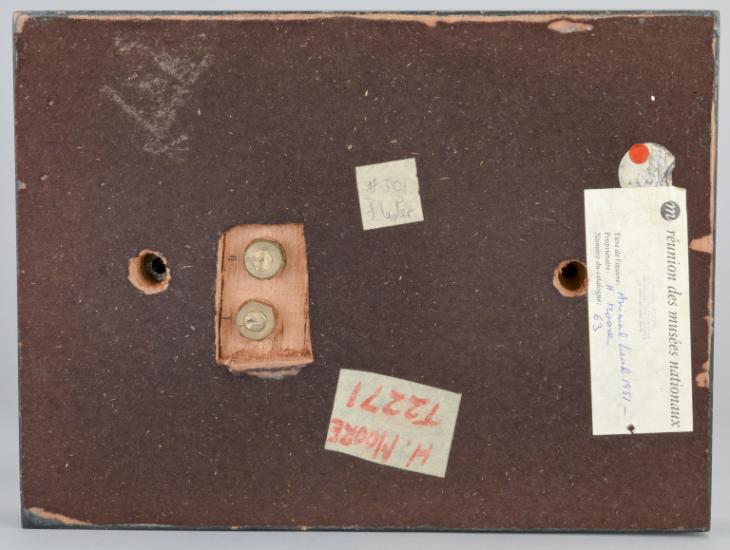

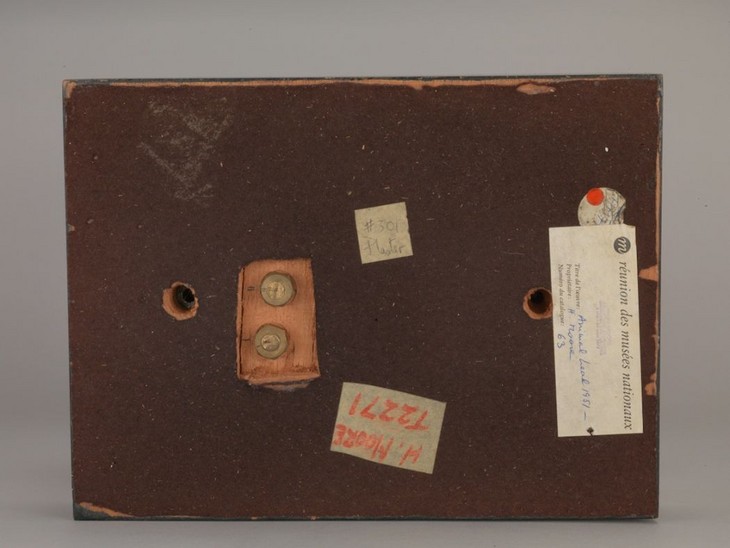

Detail of underside of base of Animal Head 1951

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of underside of base of Animal Head 1951

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

There is evidence of a past breakage to the lower jaw and neck at the base (fig.3). The fact that release agent is embedded in this broken surface suggests that this occurred before the mould was made for casting.

The animal’s neck slots over two brass rods that have been screwed through the underside of the base. There are two other holes at each end of the base indicating that it may have been used for another work at some point (fig.4). There is no signature on this sculpture.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

Notes

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Animal Head 1951 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, February 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

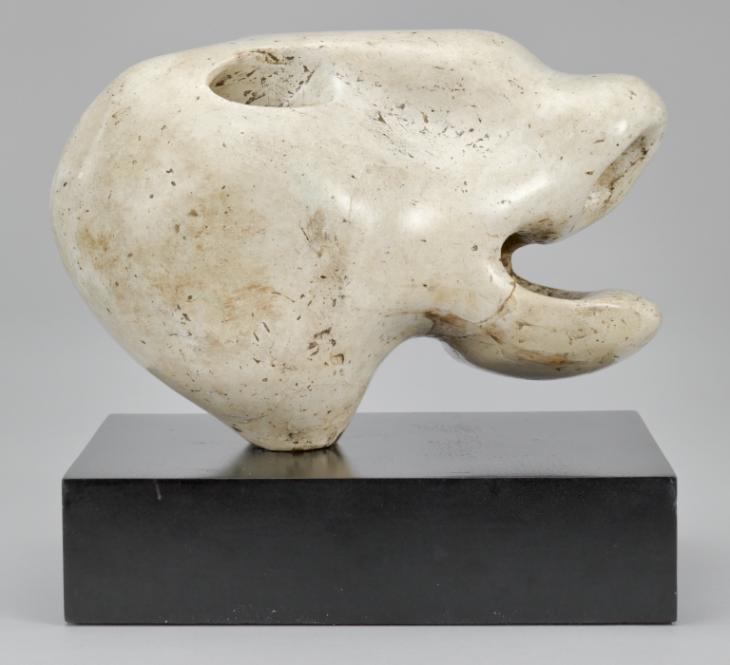

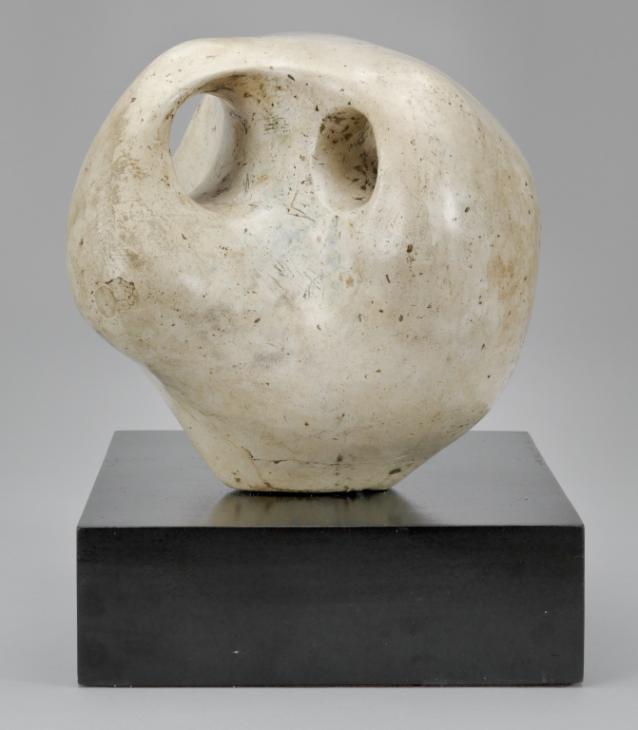

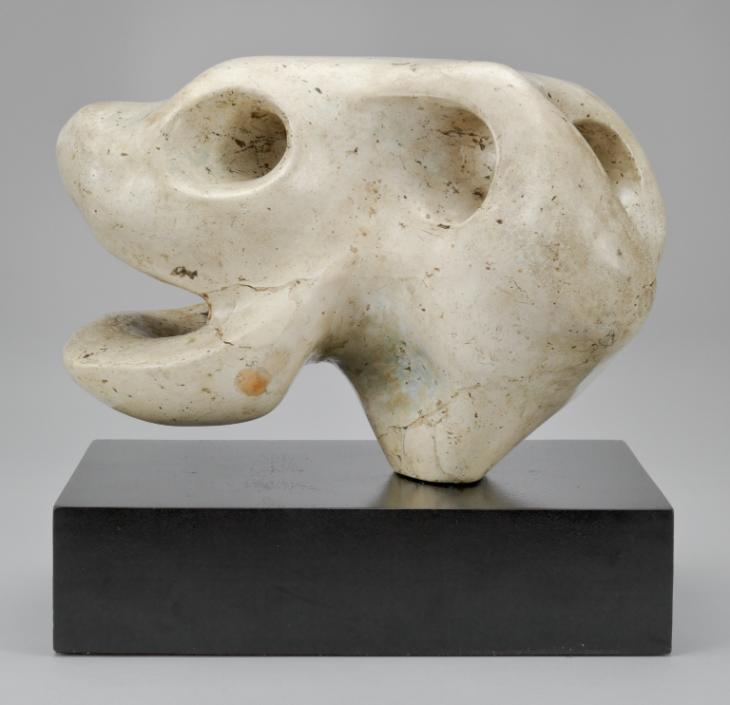

Animal Head 1951 is a sculpture of an animal’s head made in off-white plaster mounted on a rectangular wooden base spray-painted in satin black. Although it does not represent the head of a specific animal it is loosely reminiscent of a horse’s, cow’s or sheep’s head. The presence of holes that run through the plaster and its off-white surface colour give the impression that the head may represent a skull.

Henry Moore

Animal Head 1951 (side view)

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Animal Head 1951 (side view)

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Animal Head 1951 (front view)

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Animal Head 1951 (front view)

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The head appears to be balanced on a relatively small area at the base of the neck and thus seems to be front-heavy (fig.1). From the neck, the back of the sculpture curves outwards and upwards to the top of the head, which projects forwards horizontally before dipping to a snout. At the front of the snout is a shallow recess that may denote a nostril (fig.2). Below the snout is a deeper hollow with rounded edges denoting the mouth. The inside of the mouth has been coloured with a dark brown pigment to emphasise the sense of internal depth (fig.3). The thick lower jaw or mandible extends back towards the neck in parallel with the base.

Henry Moore

Animal Head 1951 (rear view)

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Animal Head 1951 (rear view)

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Animal Head 1951 (side view)

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Animal Head 1951 (side view)

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From the back of the head can be seen two holes of uneven size that run all the way through the plaster (fig.4). While the hole that can be seen on the right side of the head resembles an eye socket (see fig.1), the hole that penetrates the left side does not. Instead, on the left side an eye socket is suggested by another deep rounded recess that is positioned half-way down the length of the head (fig.5). These asymmetrical features reveal that Moore was not concerned with representing a real animal head with anatomical accuracy.

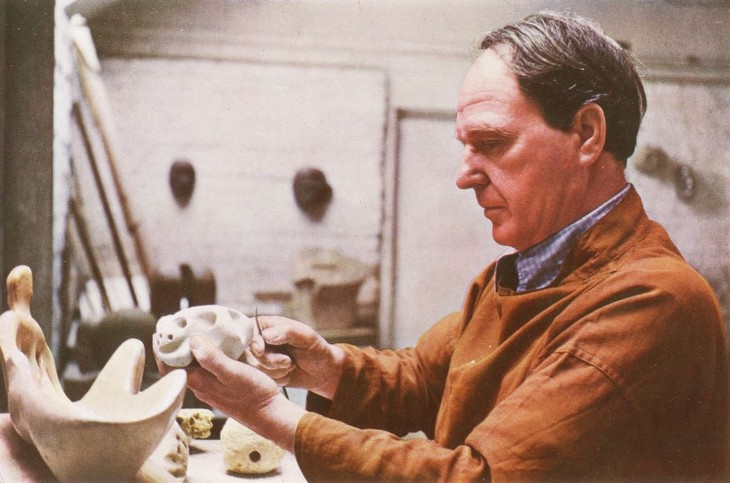

Felix Man

Henry Moore in his Studio

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Felix Man

Henry Moore in his Studio

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

This sculpture is the original plaster that was used to make an edition of eight bronze casts and one artist’s copy. Moore did not cast the bronze versions himself but instead entrusted the job to a professional foundry. At the foundry the technicians used the plaster original to create a hollow mould into which molten bronze could be poured, and from which the nine bronze versions were made.

The resultant bronze casts (see fig.7) look very different from the plaster original and complicate the idea that the sculpture represents a skull. Not only does the uniformly dark colour of the bronze version refute this interpretation but the material itself also makes certain features, such as the jaw and mouth, appear heavier, more muscular and more powerful than they do in the bone-coloured plaster. Moore later recalled that:

When working in plaster for bronze I need to visualise it as a bronze because on white plaster the light and shade acts quite differently, throwing back a reflected light on itself and making the forms softer, less powerful ... even weightless.

At first I used to have a tremendous shock going from the white plaster model to the finished bronze sculpture ... The main difference is that bronze takes on a density and weight altogether unlike plaster. Plaster has a ghost-like unreality in contrast to the solid strength of the bronze.3

At first I used to have a tremendous shock going from the white plaster model to the finished bronze sculpture ... The main difference is that bronze takes on a density and weight altogether unlike plaster. Plaster has a ghost-like unreality in contrast to the solid strength of the bronze.3

During the 1920s and 1930s Moore was known for his advocacy of direct carving and his rejection of modelling techniques, but by the 1940s he started to find the limitations of carving directly in stone and wood too restrictive. Working in plaster allowed Moore to experiment with forms that would have been impossible to achieve by direct carving, which requires sculptors to be conscious of, and make work in response to, the properties and weaknesses of particular materials. Moore started working in plaster in the early 1950s and as such Animal Head can be identified as one of his earliest sculptures in plaster.

However, when Moore first started working in plaster the sculptures he made were regarded as steps in the casting process and not as works of art in their own right. When the plasters were returned from the foundry they would often be covered in sealants and resins, or cut into pieces having been carved up into manageable sizes for casting. When Moore started working in plaster he often destroyed the original sculptures after all the bronzes in the edition had been cast to ensure that no additional, unauthorised copies could be made. However, due to the large demand for his work to be seen in exhibitions Moore occasionally exhibited plaster originals when bronze versions were unavailable. This plaster original of Animal Head was included in his 1951 solo exhibition at the Leicester Galleries, London, probably before the bronze editions were cast.

Over time Moore’s attitude towards his plasters changed, and he began to see them not simply as intermediary stages in the casting process but as unique works of art. In the early 1970s Moore declared, ‘These are not plaster casts; they are plaster originals ... they are actual works that one has done with one’s hands’.4 In 1973 Moore recounted the moment when he started to reconsider the value of his plasters:

A friend who works at the Victoria and Albert Museum came out one day just as we were breaking up some plasters and said, ‘But why do that, because sometimes the original plaster is actually nicer to look at than the final bronze’. He was right because sometimes an idea you’ve had and that you’ve made in the original material or plaster can suit it better than what the final bronze may do ... So, this led to the idea of not destroying the plasters, leaving me with a great many of them that I would not sell but wanted to find proper homes for.5

Since he wanted to avoid casts being made without his permission, Moore did not want to sell the plasters on the open market. He therefore decided to include his plasters in his philanthropic gifts to the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto, where he presented 131 sculptures between 1974 and 1986, and the Tate Gallery in 1978. The Henry Moore Gift to the Tate Gallery included thirty-six sculptures, including five works in plaster.

Having decided to give the AGO and the Tate Gallery examples of his original plasters, in the early 1970s Moore’s studio assistants John Farnham, Michael Muller and Malcolm Woodward set about restoring and repairing the damaged plasters and removing remnants of resin sealant that had been applied to the surface of the plasters during the casting process. According to Alan Wilkinson, curator at the AGO, undertaking this work revealed ‘more clearly the extraordinary variety of surface details and textures, each of the original plasters having its own unique surface colouring and tonality’.6 In the case of Animal Head, the plaster is revealed to be not a stark white, but a softer cream colour, highlighted with touches of brown and aquamarine. According to Anita Feldman, co-author of Henry Moore: Plasters (2011), Moore often coloured his plaster ‘with walnut crystals to give the sculptures an organic warmth’, while a pale green wash was used ‘to emulate the bronze dust which often accumulated on them over time in the foundries’.7

Stones on a shelf in Moore's studio at Hoglands

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Stones on a shelf in Moore's studio at Hoglands

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore’s interest in naturally weathered stones had been sparked in the late 1920s and became firmly established while looking at flint pebbles on the beach during visits to north Norfolk in 1930–1. In 1934 Moore stated that ‘The observation of nature is part of an artist’s life, it enlarges his form-knowledge’.11 For Moore it was ‘form-knowledge’ that made it possible to draw connections between, for example, the holes in weathered stones and the eyes and nostrils of animals. In 1937 Moore articulated his appreciation of holes in his article ‘A Sculptor Speaks’, published in the Listener magazine:

Pebbles show nature’s way of working stone. Some of the pebbles I pick up have holes right through them ... A piece of stone can have a hole through it and not be weakened – if the hole is of a studied size, shape and direction. On the principle of the arch, it can remain just as strong. The first hole made through a piece of stone is a revelation. The hole connects one side to another, making it immediately more three-dimensional. A hole can have as much shape-meaning as a solid mass. Sculpture in air is possible, where the stone contains only the hole, which is the intended and considered form. The mystery of the hole – the mysterious fascination of caves in hillsides and cliffs.12

Having garnered the ‘form-knowledge’ of naturally occurring objects, Moore was able to utilise those shapes imaginatively in his sculptures. For Moore the study of pebbles, rocks or bones was a way of learning not only about natural materials and their forms, but also about how nature’s energies acted upon organic material; inherent to the forms of natural materials are the powerful processes of erosion, weathering and decay that shaped them.

Moore made his first sculpture of an animal head, Small Animal Head (The Henry Moore Foundation), in 1921, and although the subject featured infrequently in his work, it was nonetheless one that he liked to return to, with the last examples being made in the early 1980s. Indeed, as early as 1934 the critic Herbert Read identified animals as one of Moore’s key interests. Although written well before the creation of Animal Head, Read’s observations remain relevant. According to Read, Moore’s animal sculptures from the 1920s were reduced to certain basic shapes or features in an attempt to convey the animal’s inner character.13 Moore’s animals, Read argued, did not aspire to anatomical accuracy but were presented in distilled, unembellished forms that conveyed their inherent life force, or essence. This essence may be understood in relation to Moore’s own notion of vitality as it was articulated in a short essay he published in Unit One. In this statement Moore explained that ‘For me a work must first have a vitality of its own. I do not mean a reflection of the vitality of life, of movement, physical action, frisking, dancing figures and so on, but that a work can have in it a pent-up energy, an intense life of its own, independent of the object it may represent’.14 For Alan Wilkinson, ‘Animal Head is a text book embodiment of Moore’s oft quoted statement on “Vitality and Power of Expression”, in his contribution to Unit One’ cited above.15

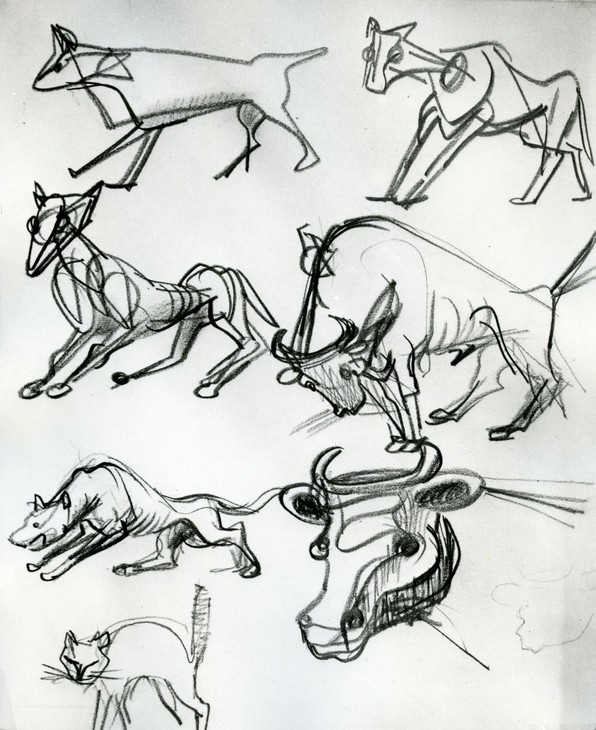

Henry Moore

Animal Studies c.1950

Graphite on paper

289 x 238 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Animal Studies c.1950

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Animal Heads c.1950

Graphite, wax crayon and watercolour wash on paper

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Animal Heads c.1950

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

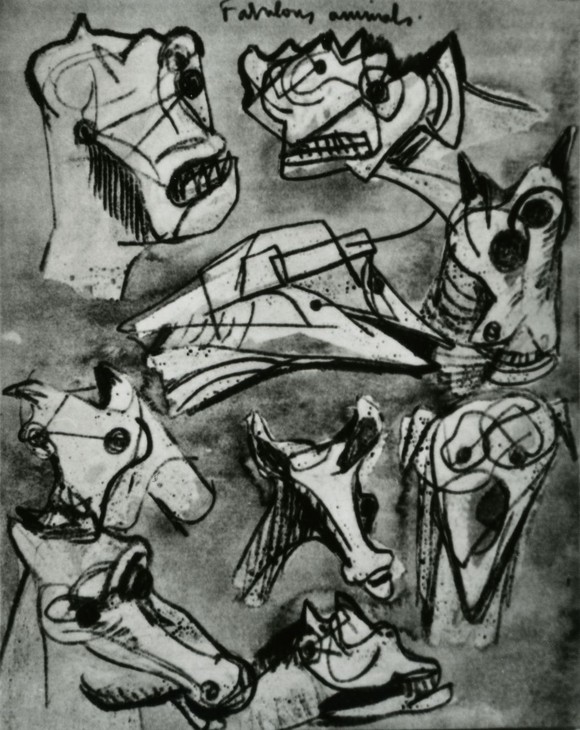

Because the maquette for Animal Head was made in Moore’s plaster studio, amid his ‘library of natural forms’, there are no preparatory drawings relating specifically to the sculpture. However, in 1950 Moore did make seven pages of related studies of animal heads and fantastical animals. Although the order in which Moore made these drawings is uncertain, it is possible that he began with some naturalistic sketches, such as that of the cow’s head in the lower right of Animal Studies c.1950 (fig.9), and developed these into more abstract creatures, as seen in Animal Heads c.1950 (fig.10).16 These drawings reveal that Moore was aware of the anatomical structure of animals, and was curious about how these living beings might be expressed creatively.

Henry Moore

Fabulous Animals c.1950

Wax crayon, coloured crayon and watercolour wash on paper

Whereabouts unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Fabulous Animals c.1950

Whereabouts unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

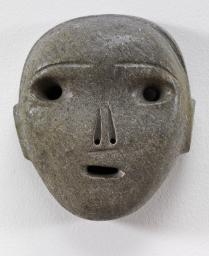

Rudolph continued that Moore’s interest in fantastical or grotesque animals may be traced to the artist’s interest in ancient American art in the British Museum, and the studies he undertook there in the 1920s and 1930s. Moore’s knowledge of the arts of ancient Mexico originated from his reading of the art critic Roger Fry’s Vision and Design (1920) as a student at Leeds School of Art in 1920. Fry had included a chapter on ancient American arts in his book, and Moore later recalled that ‘Fry opened the way to other books and to the realisation of the British Museum. That was the beginning really’.19 The British Museum had a particularly large collection of ancient Mexican sculpture having acquired its first piece in the 1820s. In 1947 Moore recalled ‘One room after another in the British Museum took my enthusiasm ... And after the first excitement it was the art of ancient Mexico that spoke to me most’.20 Although she does not cite her source, art historian Barbara Braun claims that ‘Moore himself once attributed the piercing of his sculptures of the late 1930s to the Mexican stimulus, citing as inspiration a giant perforated parrot head ... from Xochicalco, in which positive and negative spaces have equal value’.21 This perforated head of a bird may have resonated with Moore and perhaps demonstrated to him how living natural forms could be abstracted to express a sense of ‘vitality’ while retaining a resemblance to their real appearance.

Three years before Moore’s death, the art historian W.J. Strachan published his book Henry Moore: Animals in which he suggested that ‘the “animal heads” ... compose some of Moore’s most original and at the same time disquieting creations’.22 He went on to describe Animal Head as a ‘grinning skull-like form’ that is ‘hauntingly assertive’.23 Wilkinson agreed that the sweeping forms and tunnels of Animal Head suggest ‘a skull rather than a living head ... Two holes, like massive bullet wounds, run diagonally through the side of the head and out the back. This is as haunting and disturbing an image of the animal world as Picasso’s bronze and copper Deaths Head 1943 is of the human’.24 Moore was perhaps able to instill Animal Head with ‘haunting’ disquiet because the subject of the sculpture was zoological rather than human. He later recounted that ‘sometimes I feel freer when working on an animal idea because I can invent an imaginary animal. I would find it less natural to try and alter a human’.25

After the bronze edition of Animal Head had been cast the plaster original was returned to Moore and remained in his possession. The plaster was kept and displayed in his maquette studio alongside other plaster and terracotta maquettes, and among his collection of stones, bones and other natural forms.

Animal Head was presented by Henry Moore to the Tate Gallery in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift. The Gift comprised thirty-six sculptures in bronze, marble and plaster and was exhibited in its entirety alongside Tate’s existing collection of Moore’s work in an exhibition celebrating the artist’s eightieth birthday, which opened in June 1978. A press release was duly prepared announcing that ‘The group [of sculptures] is the most substantial gift of works ever given to the Tate by an artist during his lifetime’.26 Animal Head was included in the exhibition and displayed in gallery twenty-six alongside Upright Internal/External Form 1952 (Tate T02272). The exhibition was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.27 At the close of the exhibition in late August 1978 the Director of Tate Norman Reid reflected in a letter to Moore’s daughter Mary Danowski that although he was sad to see the exhibition come to an end ‘we have the consolation of the splendid group of sculptures which Henry has presented to the nation’.28

Alice Correia

February 2013

Notes

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, p.113, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.226.

Henry Moore cited in John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore: My Ideas, Inspiration and Life as an Artist, London 1986, p.159.

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.18.

Anita Feldman, ‘Moore: The Plasters’, in Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011, pp.12, 19.

Henry Moore, ‘Statement for Unit One’, in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, pp.29–30, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.192.

Henry Moore, ‘A Sculptor Speaks’, Listener, 18 August 1937, pp.338–40, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.195.

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Animal Head, Lot 62’, British & Irish Art Auction: Sale 7595, sales catalogue, Christie’s, London 2008, http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/sculptures-statues-figures/henry-moore-om-ch-animal-head-5088887-details.aspx?pos=3&intObjectID=5088887&sid=&page=5 , accessed 5 February 2013.

This developmental sequence is based on the way in which these drawings are presented in the artist’s catalogue raisionné, where Animal Studies c.1950 is listed before Animal Heads c.1950. See Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Drawings 1950–76, London 2003, p.20.

Reinhard Rudolph, ‘Animal Head, 1951’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works From the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.231.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeny, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.44.

Barbara Braun, Pre-Columbian Art and the Post-Columbian World: Ancient American Sources of Modern Art, New York 2000, p.122.

Related essays

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

Related reviews and articles

- Henry Moore, ‘The Sculptor Speaks’ Listener, 18 August 1937, pp.338–40.

Related bibliography

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Animal Head 1951 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, February 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www