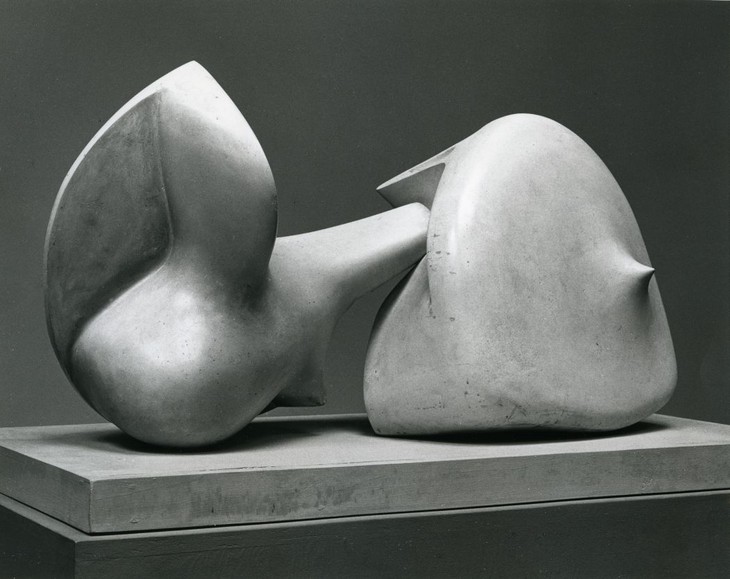

Henry Moore OM, CH Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Image 1 of 12

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe

1966, cast date unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

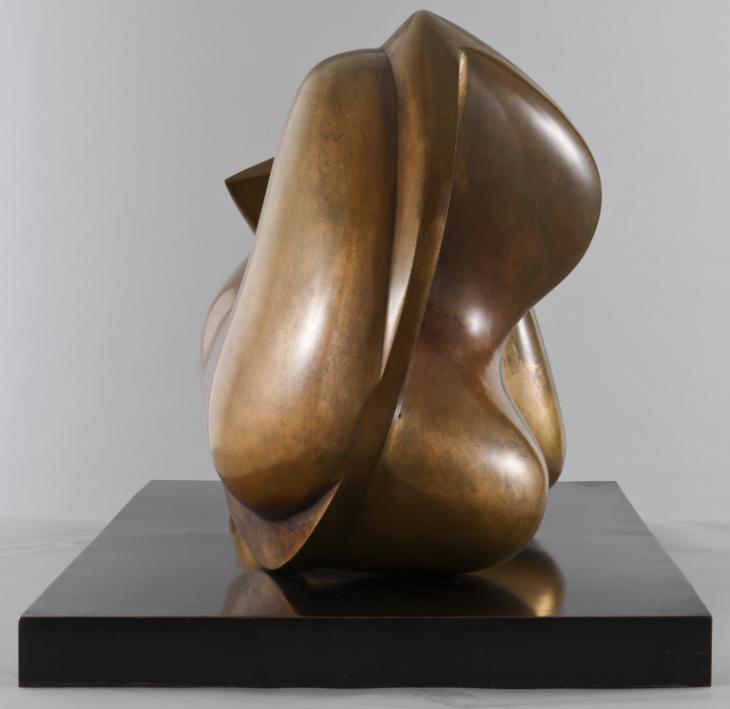

Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe is one of a series of two-piece sculptures made during the 1960s that relate to Moore’s interest in bone forms. The projecting beam that bridges the two parts has been interpreted by critics as a phallic appendage, which has led the sculpture to be seen as a highly abstract representation of sexual coupling.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe

1966, cast date unknown

Bronze

432 x 839 x 315 mm

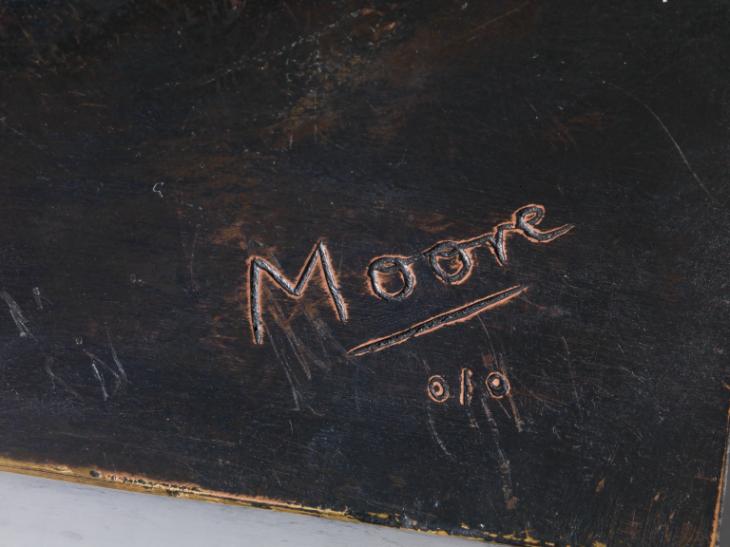

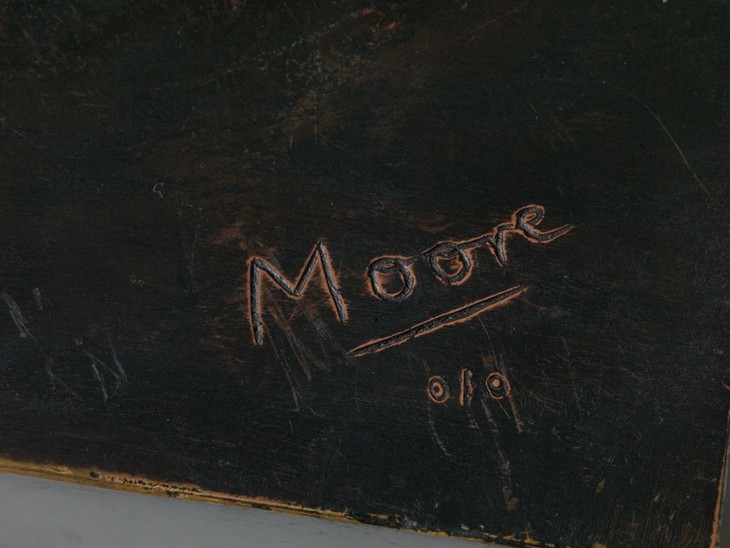

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/0’ on base

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 9

T02300

Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe

1966, cast date unknown

Bronze

432 x 839 x 315 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/0’ on base

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 9

T02300

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1968

Henry Moore, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, May–July 1968; Museum Boymans-Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, September–November 1968, no.118.

1968

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968, no.136.

1968

Henry Moore, Heslington Hall, York, March 1969, no.39.

1969

Henry Moore: Drawings and Sculpture, Gordon Maynard Gallery, Welwyn Garden City, July 1969, no.8.

1971

Henry Moore, Musée Rodin, Paris, 1971 (?another cast exhibited no.49).

1971

Henry Moore 1961–1971, Staatsgalerie Moderner Kunst, Munich, October–November 1971, no.25.

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972, no.141.

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, Zürcher Forum, Zürich, June–August 1976, no.82.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, Palacio de Velázquez, Palacio de Cristal and Parque de El Retiro, Madrid, May–August 1981, no.70.

1981

Henry Moore, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, September–November 1981, no.106.

1982–3

Henry Moore en México: Escultura, Dibujo, Grafica de 1921 a 1982, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City, November 1982–January 1983, no.45.

1983

Henry Moore: Esculturas, Dibujos, Grabados – Obras de 1921 a 1982, Museum of Contemporary Art, Caracas, March 1983, no.112.

References

1966

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Fine Art, London 1966 (another cast reproduced no.19 as Two Piece Reclining Figure No.7).

1967

David Jolley, ‘Henry Moore: Two-Piece Sculpture 1966, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester’, Burlington Magazine, vol.109, no.774, September 1967, p.533 (another cast reproduced p.535).

1967

Albert Elsen, ‘The New Freedom of Henry Moore’, Art International, vol.11, no.7, September 1967, pp.42–5 (?another cast reproduced p.44).

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, p.193 (?another cast reproduced pl.198).

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, p.504 (?another cast reproduced p.442).

1968

Ionel Jianou, Henry Moore, Paris 1968, no.521 (another cast reproduced pl.33).

1968

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Rijksmuseum Kröller–Müller, Otterlo 1968, reproduced no.118.

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, pp.38, 141, reproduced pls.29, 133.

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, p.301 (?another cast reproduced pl.700).

1970

Henry Moore: Carvings 1961–70, Bronzes 1961–70, exhibition catalogue, M. Knoedler & Co., New York 1970 (another cast reproduced p.63).

1971

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Musée Rodin, Paris 1971 (?another cast reproduced).

1971

Giulio Carlo Argan, Henry Moore, Milan 1971 (?another cast reproduced pl.197).

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Forte di Belvedere, Florence 1972, reproduced p.208.

1973

Henry J. Seldis, Henry Moore in America, New York 1973 (another cast reproduced p.239).

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973 (another cast reproduced pl.126).

1977

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977 (?another cast reproduced pls.38–9).

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, exhibition catalogue, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris 1977 (original plaster reproduced p.178).

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Cartwright Hall, Bradford 1978 (?another cast reproduced no.40).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.58.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

1979

1979, p.195 (original plaster reproduced pl.171).

1981

The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.139–40, reproduced p.139.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, exhibition catalogue, Palacio de Velázquez, Madrid 1981, reproduced pls.407–8.

1983

Henry Moore: Esculturas, Dibujos, Grabados – Obras de 1921 a 1982, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Contemporary Art, Caracas 1983, reproduced p.110.

1983

William S. Liederman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983 (another cast reproduced p.96).

1984

Henry Moore: The Reclining Figure, exhibition catalogue, Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus 1984 (another cast reproduced p.78).

Technique and condition

Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe is a two-part abstract bronze sculpture mounted on a rectangular base. Moore would have made the original model for this sculpture in plaster (fig.1), which was built up in successive layers over a supportive armature that was probably made from wood and chicken wire. After the hardened plaster had been sanded smooth, moulds were taken of each part that were used to cast the sculpture in bronze.

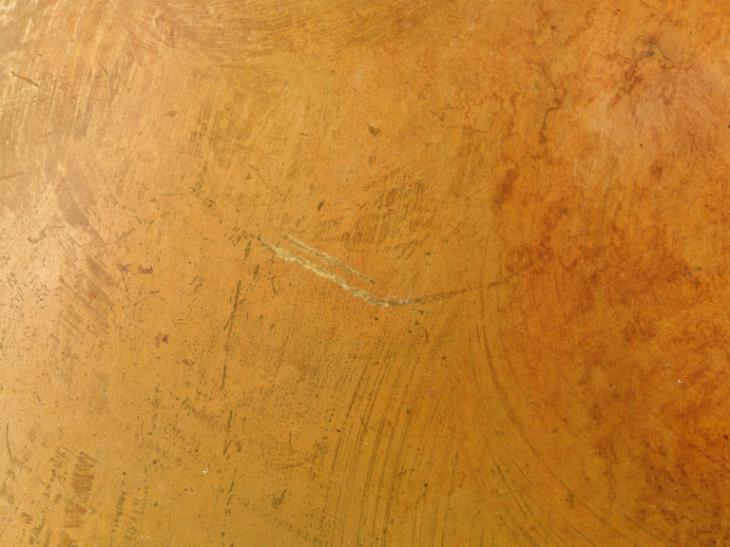

The two elements were probably sand cast, although their finely polished surfaces hide traces of the casting technique. After casting the sculpture was artificially patinated a transparent chestnut brown colour, mainly in the recesses (fig.2). This colour is produced by stippling a chemical solution onto the bronze while the surface is heated using a blowtorch. Ferric nitrate is often used by foundries to produce this colour, but it can also be used to produce a range of other colours, from transparent orange to a deep opaque plum.

Detail of patina on Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of patina on Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of streaks on surface of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of streaks on surface of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

A brush was used to apply a lacquer over the surface of the bronze to protect it and prevent it from tarnishing. However, the lacquer has begun to break down in places, which has allowed the bronze to tarnish in patches and streaks (fig.3). The tarnish is particularly evident on the most prominent surfaces at the top, probably due to handling over the years.

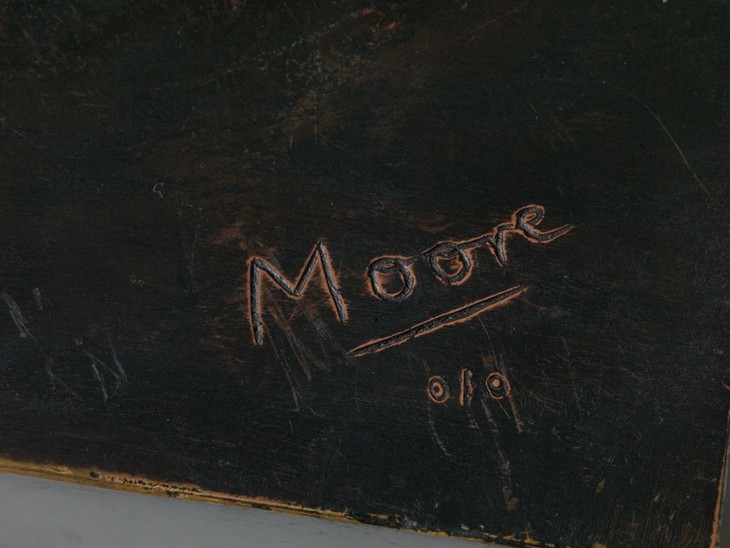

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on base of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on base of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

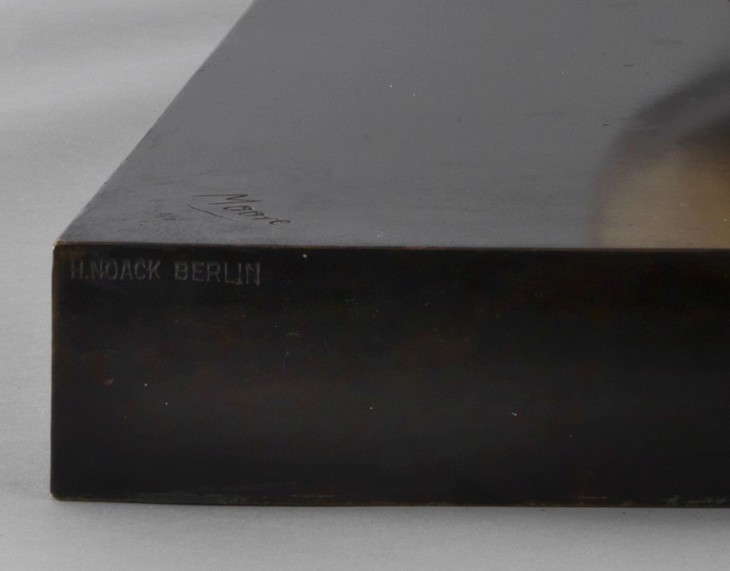

Detail of foundry stamp on base of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of foundry stamp on base of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The two parts of the sculpture are fixed close together on the base. Two bolts have been used to fix one part and three bolts for the other. The base is likely to have been sand cast and has a smooth surface patinated an even dark brown colour. The artist’s signature ‘Moore’ is inscribed on the top of the base in one of the corners accompanied by the edition number ‘0/9’ (fig.4). The foundry mark ‘H.NOACK BERLIN’ is stamped on the side of the base at the same corner (fig.5).

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, July 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

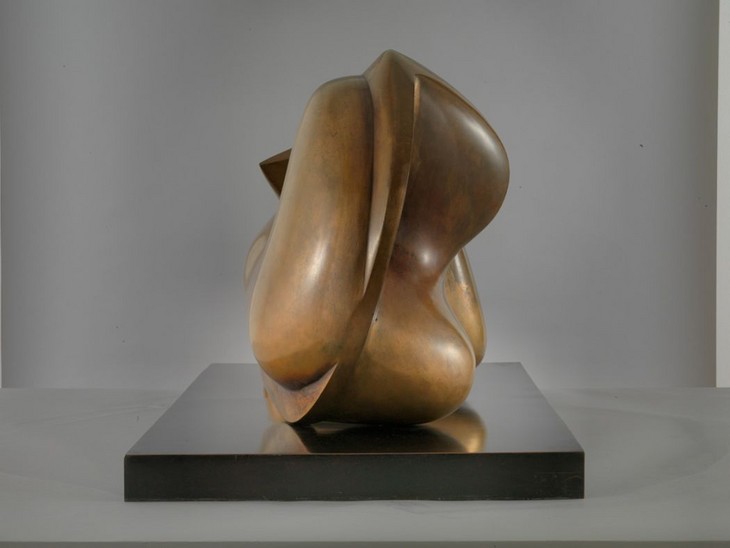

Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe comprises two highly polished abstract forms positioned on a bronze base (fig.1). These elements are evenly sized but differently shaped and are made up of both angular and rounded forms. Although they are placed at a short distance from each other, the gap between them is bridged by a beam that extends out horizontally from one element and touches the other at a single point (fig.2).

Henry Moore

Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of interlocking parts of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of interlocking parts of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Seen from one side, the element with the extended beam is reminiscent of a smoking pipe – the arm may be understood as the long mouth-piece and the rounded form the tobacco barrel (fig.3) – which may explain the sculpture’s subtitle. This rounded element appears to have been constructed around a thin circular disk, from which bulbous forms extend on either side (fig.4).

Detail of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The other piece of the sculpture comprises one side that is almost completely flat and smooth except for a single raised point or nipple, located just to the right of centre (fig.5). Like the bulbous forms of the accompanying piece, two protrusions extend out from the other side of this flat, disk-like surface (fig.6). The larger of the protrusions creates a diagonal arc from the lower left to the top right. Towards the lower part of this element is a large concave extension, which rests on the base.

Henry Moore

Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Detail of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From plaster to bronze

This sculpture was developed from a small maquette made in plaster in 1966. By this time Moore had established a practice of testing out his designs for sculptures by making small three-dimensional models as opposed to drawing his ideas on a page. In 1978 he explained:

I have gradually changed from using preliminary drawings for my sculptures to working from the beginning in three-dimensions. That is, I first make a maquette for any idea I have for a sculpture. The maquette is only three or four inches in size, and I can hold it in my hand, turning it over to look at it from above, underneath, and in fact from any angle.1

It is probable that Moore made the small model for this sculpture in his maquette studio in the grounds of his home, Hoglands, at Perry Green in Hertfordshire. This studio housed his ever growing collection of found objects, including bones, shells and flint stones, the shapes of which often served as starting points for Moore’s formal experiments in three dimensions. In 1963 Moore explained to critic David Sylvester how he worked with these objects:

I look at them, handle them, see them from all round, and I may press them into clay and pour plaster into that clay and get a start as a bit of plaster, which is a reproduction of the object. And then add to it, change it. In that sort of way something turns out in the end that you could never have thought of the day before.2

It is likely that the two parts of the maquette for Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe were developed from plaster casts of the impression left by a stone or bone pressed into clay, for the flat edges around the bulbous protrusions conform to the top surface of a mould. Once these pieces of plaster had hardened, Moore could add and subtract forms, and smooth or sharpen edges and points to his preferred design, so that the final work was ‘not a copy of nature, but built on nature’s principles’.3 Moore would then have used the maquette as a model for Tate’s larger-scale work. By charting and measuring specific points on the surface of the maquette it was possible to make an exact enlargement of the sculpture. Much, if not all of this work would have been undertaken by Moore’s studio assistants, who in 1966 included Hans Drews, John Farnham and Yardini Yeheskiel.

In order to make the full-size plaster from which Tate’s bronze was eventually cast, Moore and his assistants would have initially constructed an armature to the required size and shape for each section of the sculpture. The armature was made up of numerous lengths of wood, and possibly chicken wire. This structure was then draped in scrim, a bandage like fabric, onto which wet plaster could be applied to create a hard shell. Layers of plaster were then built up to create the basic shape while the interior of the plaster remained hollow.

Henry Moore

Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966

Plaster

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Once Moore was satisfied with the surface finish of the sculpture and was sure that he wanted to proceed with the casting process, he sent the two plaster parts to the Noack Foundry in West Berlin to be cast in bronze. In 1967 Moore stated, ‘I use the Noack foundry for casting most of my work because in my opinion, Noack is the best bronze founder I know ... Also, the Noack foundry is reliable in all ways – in keeping to dates of delivery – and in sustaining the quality of their work’.6 The sculpture was probably made using the sand casting method, although the finely polished surfaces of the bronze hide the traces of the casting technique.

After casting at the foundry the bronze sculpture would have been returned to Moore so that he could check the quality of the casting and make decisions about the patination. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze surface. Publicly Moore always maintained that he patinated his works himself, and rarely acknowledged that this physical work would have been undertaken by his assistants. It is also known that during the 1960s, as Moore increased his sculptural production and more of his works were editioned, Noack would sometimes patinate his sculptures for him at the foundry. Moore made regular visits to the foundry and could adjust the patina when he felt it necessary. Tate’s cast of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe has been coated with a warm chestnut brown patina but there is some colour variation across the sculpture: the edges and protrusions are lighter in colour while the recessed areas are darker (fig.8). Streaky brushstrokes are visible on the surface, which, according to conservator Lyndsey Morgan, indicate where the protective lacquer coating has broken down (fig.9).

Detail of patina on Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Detail of patina on Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of streaks on surface of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Detail of streaks on surface of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on base of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on base of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown

Tate T02300

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

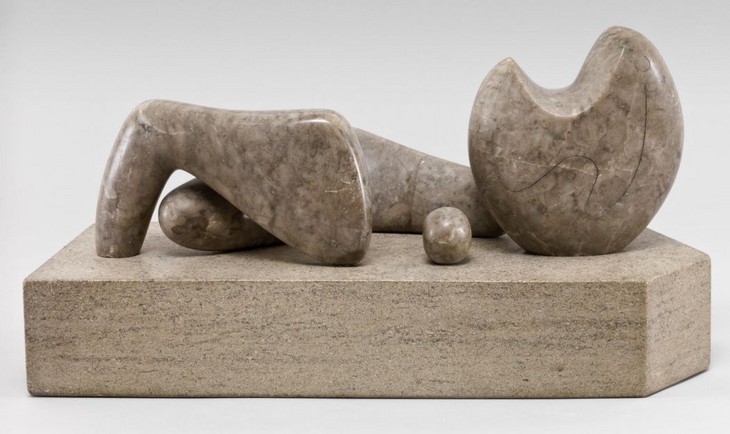

Origins and interpretation

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Cumberland alabaster on a Purbeck marble base

175 x 457 x 203 mm

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In his maquette studio at Hoglands Moore surrounded himself with pebbles, flint stones and shells as well as bone fragments, all of which were used as source material for his sculptures. The art historian Herbert Read argued in 1934 that, by drawing upon the shapes of these natural forms, Moore was able to break free from the ‘false imprisonment’ of mimetic representation and yet retain an organic energy within his work.11 References to bones and other organic forms in interpretations of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe are supported not only by knowledge of Moore’s working methods, but also by statements he made on the importance of natural forms for artistic creativity. In 1934 Moore wrote that ‘the observation of nature is part of an artist’s life; it enlarges his form-knowledge, keeps him fresh from working only by formula, and feeds inspiration. The human figure is what interests me most deeply, but I have found principles of form and rhythm from the study of natural objects such as pebbles, rocks, bones, trees, plants, etc’.12 These principles underpinned Moore’s later work and anticipated his comment, made in 1967, that when looking for human resonances in natural forms ‘taste is not the guide. I’m not interested in the niceties of a shape’.13 By breaking down the body into distinct parts derived from natural forms, Moore sought to identify the figure with the earth, and humanity with its environment, expressing their union in an ‘organic whole’.14

In Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe Moore combined his interest in the human figure with his concurrent explorations of interlocking forms. After separated the body into two distinct parts in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Moore then began thinking about ways in which separate sculptural parts could intersect or interlock to create a single unit while maintaining their individuality. These ideas came to fruition in works such as Locking Piece 1963–4 (Tate T02293), in which two differently shaped elements intersect. According to Bowness, it was the relationship between the two parts of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe that was of interest to Moore, and the subsequent omission of the term ‘Reclining Figure’ from its title reflected these concerns. As Bowness made clear, ‘the sub-titles bestowed on these sculptures by the artist ... [are] names of convenience, applied after the work is made, to help distinguish one piece from another, and not of any great significance except that names like Pipe, Interlocking, Points do suggest the theme of connexion which the sculptures embody’.15

Moore made only one known statement about Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe. Discussing the sculpture in 1968, he stated:

I call this sculpture ‘Two-piece: Pipe’. It is an attempt to make a sculpture which is varied in all its views and forms. One piece is very different from the other, and by combining the two I obtain many permutations and combinations. By adding two pieces together the differences are not simply doubled. As in mathematics, they are geometrically multiplied, producing an infinite variety of viewpoints.16

Evidently, in developing his ideas for Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe Moore was particularly interested in how the sculpture would be experienced in the round. That this formal concern became an organising principle of this work illustrates continuity between Moore’s experiments of the 1960s and his earlier ideas and aspirations for sculpture. In his statement for the 1934 publication Unit One he wrote:

Sculpture fully in the round has no two points of view alike. The desire for form completely realised is connected with asymmetry. For a symmetrical mass being the same from both sides cannot have more than half the number of different points of view possessed by a non-symmetrical mass.17

In his statement Moore also related his asymmetrical sculptures to naturally occurring forms, asserting that ‘asymmetry is connected also with the desire for the organic (which I have) rather than the geometric. Organic forms, though they may be symmetrical in their main disposition, in their reaction to environment, growth, and gravity, lose their perfect symmetry’.18 The formal connections that can be made between Moore’s work of the 1930s and 1960s are what most likely prompted the curator David Sylvester to describe the bronzes of the 1960s as originating from ‘a biomorphic abstract sculptural language’.19 Coined in the 1930s by the critic Geoffrey Grigson, the term ‘biomorphic’ denoted, according to the art historian Jennifer Mundy, ‘an organic quality that was an indelible residue of the way in which the form had been arrived at’.20 While the term could infer a likeness to forms produced by organic processes, it ‘did not necessarily imply that the form looked like anything real’.21

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.1 1959

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.1 1959

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Two Reclining Figures 1961

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, felt-tipped pen and watercolour wash on paper

613 x 524 x 31 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Menor, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Two Reclining Figures 1961

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Menor, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Although the figurative references in Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe are minimal, some commentators, including the curator Alan Wilkinson, have identified a sexual aspect to the way in which the ‘pipe’ attempts to penetrate the second form. Wilkinson argued in 1987 that in Moore’s work of the 1960s, there is ‘an overt sexuality rarely encountered in his earlier work’.22 Similarly, Bowness remarked that in Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe ‘penetration of one form into another seems to refer obliquely to the sexual relationship, and the pipe is an obvious phallic form’.23 This interpretation is in keeping with Sylvester’s assessment of Moore’s two-piece series as a whole. The critic asserted in 1968 that ‘this series presents by far the most specifically sexual imagery in Moore’s work’.24 For Sylvester, what Moore had described as a ‘looming leg’ in Two Piece Reclining Figure No.1 1959 (fig.12), can in fact be understood as a phallus and it is possible to apply this interpretation to the projecting beam of Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe.25 Sylvester supported his reading of the two-piece sculptures with reference to the drawing Two Reclining Figures 1961 (fig.13). The sketch towards the top of the page appears to be a drawing of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.1, while Sylvester’s description of the drawing below it seems to describe the act of fellatio: ‘the lower half is a huge mouth opened wide to receive an inexplicably elongated form sticking out of the torso’.26 Reflecting on the ‘erotic’ undertones of Moore’s two-piece sculptures, the artist’s biographer Roger Berthoud observed that ‘Two Piece Sculpture No.7 – Pipe is the most obviously phallic, but there is a recurring sense of upward straining or outward-thrusting members or of actual or imminent coupling in these bronzes’.27

As well as describing the beam as a phallus, critics have identified the rounded form as a breast with a pointed nipple. Wilkinson, for example, observed in 1987 that ‘the projection in the form at the right suggests a nipple’.28 In this work, then, it would seem that Moore sought to distill male and female bodies into a penis and a breast, which he seemed to acknowledge in 1967 when the critic Albert Elsen recorded that Moore recognised that his recent works ‘have more of a repertory or mixture of parts from the body. The Pipe has all sorts of reminiscences of other things such as a breast at the right, and I know it is like a breast’.29

Writing in 1970, before Bowness and Berthoud, the critic Robert Melville proposed that Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe represented violent sexual intercourse, asserting that in this sculpture, Moore ‘takes up the Classical theme of Rape ... the two forms do not signify a divided figure: they are separate organisms, and one of them emblemizes the importune male’.30 Melville’s recourse to the ‘Classical theme’ of rape allowed him – and his readers – to consider the violent and sexualised forces at work in Moore’s sculpture without regard to contemporary definitions and understandings of the term ‘rape’. As the historian Helen Morales has argued, ‘“rape” in our commonly accepted, though not uncontroversial, sense of the word (sexual intercourse without the woman’s consent) did not exist as a concept in classical antiquity’.31

The Henry Moore Gift

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery June–August 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.14

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery June–August 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Alice Correia

July 2013

Notes

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, BBC Radio, broadcast 14 July 1963, p.18, Tate Archive TGA 200816. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

Henry Moore in ‘Interview: Conversation between Sir [sic] Henry Moore, Wolfgang Fischer and Erich Steingräber in Much Hadham on April 3, 1978’, in Erich Steingräber, Henry Moore Maquetten, Munich 1978, p.55.

David Jolley, ‘Henry Moore: Two-Piece Sculpture 1966, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester’, Burlington Magazine, vol.109, no.774, September 1967, p.533.

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Fine Art, London 1966 (another cast reproduced no.19 as Two Piece Reclining Figure No.7).

Henry Moore, letter to Martin Butlin, 13 April 1961, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23945.

Henry Moore, ‘Statement for Unit One’, in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, pp.29–30, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.192.

Henry Moore cited in Albert Elsen, ‘Henry Moore’s Reflections on Sculpture’, Art Journal, vol.26, no.4, Summer 1967, p.355.

Jennifer Mundy, ‘Comment on England’, in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, p.28.

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.220.

Henry Moore cited in Albert Elsen, ‘The New Freedom of Henry Moore’, Art International,vol.11, no.7, September 1967, p.43 (original italics).

Related essays

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Ambivalence and Ambiguity: David Sylvester on Henry Moore Martin Hammer

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, July 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www