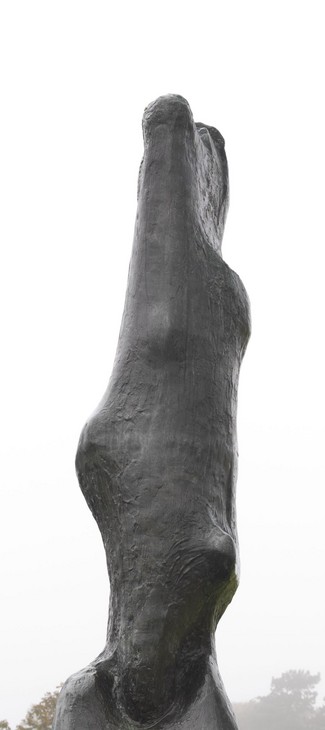

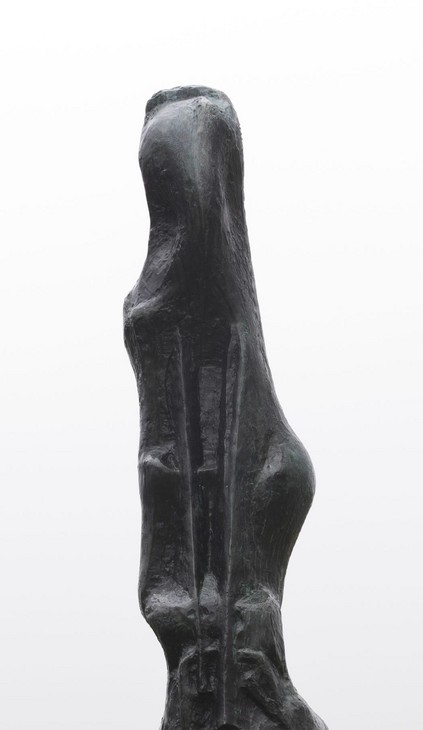

Henry Moore OM, CH Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61

Image 1 of 15

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.7 1955-6, cast c.1958-61© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Upright Motive No.7

1955-6, cast c.1958-61

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Upright Motive No.7 is one of a series of vertically orientated sculptures made by Moore between 1955 and 1956 that reflect his interest in North American totem poles and Stonehenge, and relate to the work of contemporaries including Leon Underwood and Graham Sutherland.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Upright Motive No.7

1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Bronze

3404 x 772 x 972 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 5 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02276

Upright Motive No.7

1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Bronze

3404 x 772 x 972 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 5 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02276

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1960–1

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, November 1960–January 1961, no.28.

1968

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968, no.97.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1988

Henry Moore, Royal Academy of Arts, London, September–December 1988, no.136.

2013–14

Bacon / Moore: Flesh and Bone, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, September 2013–January 2014.

References

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1960 (?another cast reproduced no.28).

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, pp.197–215.

1962

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, M. Knoedler and Co., New York 1962 (another cast reproduced pp.16–17).

1965

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, no.377 (?another cast reproduced pls.4–5).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of His Life and Work, London 1965, pp.203–8 (?another cast reproduced pl.191).

1965

Henry Moore, John Russell and A.M. Hammacher, Drie Staande Motieven, Otterlo 1965 (another cast reproduced).

1965

Anon., ‘Acquisitions of Works of Art by Museums and Galleries’, Burlington Magazine, June 1965 (another cast reproduced pp.337–45).

1966

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, pp.253–7 (?another cast reproduced pl.110).

1968

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.127 (details reproduced pls.118, 130).

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.245, 250.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.141–56 (?another cast reproduced pls.160, 162).

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, p.28, reproduced pl.507.

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973, pp.165–83 (another cast reproduced pls.100–1).

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Cartwright Hall, Bradford 1978 (another cast reproduced).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.33.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, p.139.

1981

Richard Calvocoressi, ‘Upright Motive No.7’, in The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.121–2.

1987

Henry Moore and Landscape, exhibition catalogue, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield 1987 (another cast reproduced p.18).

1989

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny 1989 (another cast reproduced p.177).

1993

David Cohen, Moore in the Bagatelle Gardens, Paris, London 1993 (?another cast reproduced pls.28–9).

1998

Margaret Garlake, New Art / New World: British Art in Postwar Society, New Haven and London 1998, pp.191–2.

2006

David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006 (another cast reproduced no.176).

2006

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fundació ‘la Caixa’, Barcelona 2006 (another cast reproduced p.144).

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (another cast reproduced p.70).

2007

Moore at Kew, exhibition catalogue, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 2007 (detail of another cast reproduced p.41).

2008

Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008, pp.203–6 (another cast reproduced no.248).

2011

Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011 (full-size plaster reproduced no.82).

2013

Richard Calvocoressi, Martin Harrison and Francis Warner, Bacon / Moore: Flesh and Bone, exhibition catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 2013, reproduced.

Technique and condition

Upright Motive No.2 1955–6, cast c.1958–62, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60, and Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Upright Motive No.2 1955–6, cast c.1958–62, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60, and Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore would have made the original model for this sculpture by applying successive layers of plaster over a supportive armature, probably made out of wood or metal. Inspection of the sculpture’s surface shows that during this process a range of techniques were used to vary the texture and articulate certain features. There are overlapping shallow waves made by adding wet plaster with a spatula, and incisions have been made in the setting plaster with serrated edges (fig.2). A number of circular depressions were also made by cutting into the surface (fig.3). In addition, Moore built the plaster up in high relief to enhance particular forms, as seen in the raised design positioned around halfway up one side of the sculpture (see fig.3).

Detail of marks on the surface of Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of marks on the surface of Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of relief decoration on Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of relief decoration on Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Once the plaster was complete a mould was taken from it so that it could be cast in hollow bronze. The maximum size of any one piece of cast bronze depends upon the size of the crucible at the foundry, as the bronze must be cast in a single pour. In practice this means that bronzes of this size are usually cast in sections, which are then welded together. This sculpture was probably cast in at least three separate pieces although the weld seams have been disguised using a technique known as ‘chasing’. This involves filing down any excess metal from the weld before texturing the bronze with punch tools to match the surrounding surface.

When the bronze had been finished and cleaned, it was coloured using an artificial patina. Chemical solutions would have been applied to the metal surface to cause a reaction that produced coloured compounds. It is possible that this sculpture was originally patinated a uniform brown colour. However, having been displayed outside for many years, its exposure to variable weather conditions has gradually altered its appearance. Most bronze sculptures displayed outdoors eventually develop a green hue as a result of weathering. This green is often brighter on exposed high points, as the sculpture’s present condition demonstrates. While situated at Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP), sheep have also affected the appearance of this sculpture. Since its foundation in 1977 YSP has worked with local farmers, allowing flocks of sheep to graze on parts of its 500 acre estate. The sheep have sought shelter around its base and their slightly abrasive wool has removed the patina, leaving visible golden edges.

When the sculpture left the foundry it would have been given a coating of protective wax. This wax, however, must be replaced annually as part of an ongoing maintenance programme. This process also involves washing the surface to remove dirt deposits and bird lime before the new wax is applied. A black wax has been used for its maintenance in the past, and this has darkened the patina and left residues in the recesses of the sculpture.

The sculpture is not signed or numbered. It is fixed to a rectangular bronze base, most likely by bolts from underneath. The base was probably cast using the sand casting technique, and its slightly rough surface suggests that it did not receive any post-casting treatment.1 Outdoor sculptures like this are usually fixed into a concrete foundation underneath the base to make them more stable.

Lyndsey Morgan

May 2013

Entry

Upright Motive No.7 is a tall, vertically orientated bronze sculpture comprising geometric shapes and amorphous, undulating forms. The lowest section consists of an oblong, lying horizontally, with a smaller cuboid stacked on top of it. One of the faces of this form curves inward at its centre and has three deep grooves carved into it (fig.1). Directly above it a series of three curvaceous forms project outwards on three sides of the sculpture (fig.2).

Detail of base of Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of base of Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of curvaceous forms on Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of curvaceous forms on Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The fourth side of the column is, by contrast, reasonably flat until approximately half way up the sculpture where a rounded, roughly bell-shaped swelling marks its widest point (fig.3). A series of approximately equidistant circular depressions have been made in its surface around three-quarters of the form’s circumference. The other side, however, has been carved to form a deep recess into which the section above appears to have been wedged (fig.4). This upper-most section is deeper than it is thick and features rounded knots or stumps on three sides leading towards a narrow apex. The other side of the column, which further down has the flatter surface, is marked by two thin raised lines that rise diagonally from the central swelling up towards the top of the column where they meet a bulbous growth that projects outwards with two recessed depressions on both sides (fig.5).

Detail of upper section of Upright Motive No.7 Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of upper section of Upright Motive No.7 Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of thin raised lines on upper section of Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of thin raised lines on upper section of Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The surface has a mottled texture produced by a variety of incisions and marks made in the surface of the plaster original. Drips and swathes of plaster, short lines made by filing tools, and more pronounced breaks in the surface – such as the circular indentations carved into its face – appear across the sculpture (fig.6).

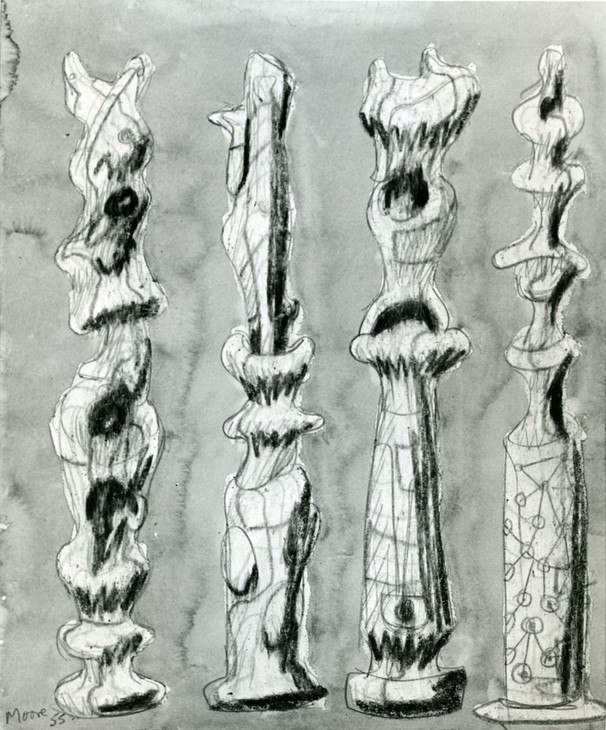

Making the Upright Motives

Upright Motive No.7 is one of a series of vertically orientated sculptures known as ‘upright motives’ made by Moore between 1955 and 1956. Moore created thirteen small bronze maquettes for individual sculptures, of which five (numbers 1, 2, 5, 7, and 8) were enlarged to full size. In addition to Upright Motive No.7, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60 (Tate T02274) and Upright Motive No.2 1955–6, cast c.1958–62 (Tate T02275) are also held in the Tate collection. Reflecting upon the origins of these sculptures in 1968, Moore recalled:

The maquettes for this upright motif theme were triggered off for me by being asked by the architect to do a sculpture for the courtyard of the new Olivetti building in Milan. It is a very low horizontal one-storey building. My immediate thought was that any sculpture that I should do must be in contrast to this horizontal rhythm. It needed some vertical form in front of it. At the time I also wanted to have a change from the Reclining Figure theme that I had returned to so often. So I did all these small maquettes. They were never used for the Milan building in the end because, at a later stage, when I found that the sculpture would virtually be in a car park, I lost interest. I had no desire to have a sculpture where half of it would be obscured most of the day by cars. I do not think that cars and sculptures really go well together.1

Henry Moore

Upright Motives 1954–6

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, pastel and watercolour wash on paper

289 x 238 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Upright Motives 1954–6

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

I have gradually changed from using preliminary drawings for my sculptures to working from the beginning in three-dimensions. That is, I first make a maquette for any idea I have for a sculpture. The maquette is only three or four inches in size, and I can hold it in my hand, turning it over to look at it from above, underneath, and in fact from any angle.4

Henry Moore

Maquette for Upright Motive No.7 1955

Plaster with surface colour

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Maquette for Upright Motive No.7 1955

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

I look at them, handle them, see them from all round, and I may press then into clay and pour plaster into that clay and get a start as a bit of plaster, which is a reproduction of the object. And then add to it, change it. In that sort of way something turns out in the end that you could never have thought of the day before.6

In 1955 Moore was just beginning to develop the working technique he described confidently to Sylvester in 1963. It is likely that Upright Motive No.7 developed from pieces of plaster cast from the impression left by a stone, bone, or shell pressed into clay or plasticine. Once these pieces of plaster had hardened, Moore could then add and subtract forms, and smooth or sharpen edges to make the final plaster maquette.

Henry Moore

Upright Motive No.7 1955–6

Plaster

3404 x 772 x 972 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Upright Motive No.7 1955–6

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Detail of casting seam on Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Detail of casting seam on Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The sculpture exists in an edition of five plus one artist’s copy. Due to the expense of casting these large bronze sculptures Moore rarely cast a whole edition at once, and in the interim the original plasters would have been retained by the foundry. Records held at the Henry Moore Foundation suggest that examples of Upright Motive No.7 were cast between 1958 and 1961.9 Indeed, letters sent between Moore and G.W. Reid at H.H. Martyn reveal that the company was making casts of Upright Motive No.7 throughout 1960.10 Although the sculpture is not signed or numbered, it is believed to be the artist’s copy.11

Moore's assistants patinating bronze sculptures from the upright motive series c.1958–60

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: John Hedgecoe

Fig.11

Moore's assistants patinating bronze sculptures from the upright motive series c.1958–60

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: John Hedgecoe

Sources and development

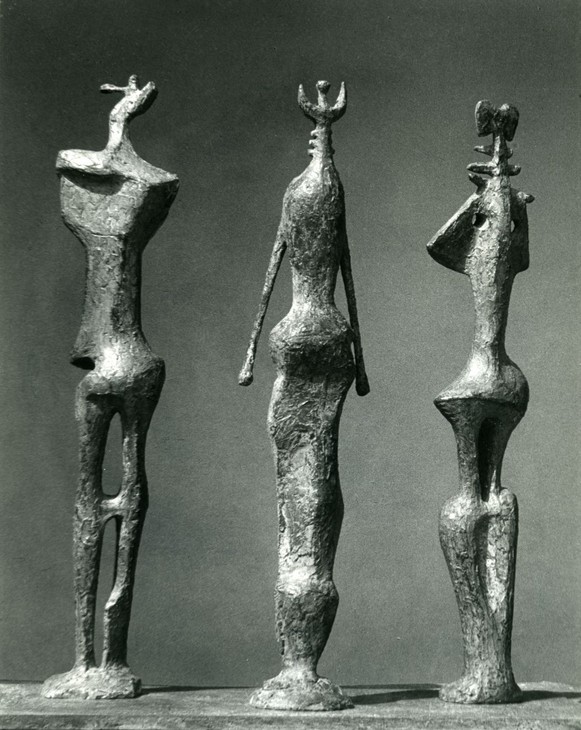

In his 1965 essay on Moore’s upright motives the critic John Russell sought to locate their origins in Moore’s previous work.13 Although at the time Moore was known chiefly for his reclining female figures, such as Reclining Figure 1951 (Tate T02270), Russell demonstrated that Moore had also subjected the upright form to consistent, albeit infrequent, examination throughout his career. From the early wood carving Torso 1927 (fig.12) and the Stringed Figure 1938 to Three Standing Figures 1953 (fig.13), Russell provided a visual chronology of Moore’s vertical standing forms to which Upright Motive No.7 may be related.14 However the upright motives may also be seen in relation to Moore’s interest in so-called ‘primitive’ art, his surrealist works of the 1930s, and the architectural commissions he undertook in the early 1950s.

Henry Moore

Torso 1927

Wood

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Torso 1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1953

Bronze

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1953

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Bird-faced figure carved by Arawak, Jamaica, c.800–1500

Wood

895 x 710 x 240 mm

© The Trustees of the British Museum

British Museum

Fig.14

Bird-faced figure carved by Arawak, Jamaica, c.800–1500

© The Trustees of the British Museum

British Museum

Leon Underwood

Totem to the Artist 1925–30

Tate T00644

© The Estate of Leon Underwood

courtesy the Redfern Gallery, London

Fig.15

Leon Underwood

Totem to the Artist 1925–30

Tate T00644

© The Estate of Leon Underwood

courtesy the Redfern Gallery, London

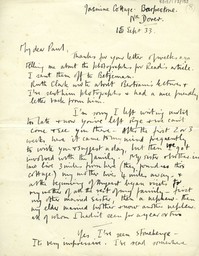

In 1965 the critic Herbert Read proposed that prototypes for Moore’s standing totems could also be found in the prehistoric standing stones of Stonehenge and Avebury Circle in south-west England and Carnac in Brittany, France.18 Moore first visited Stonehenge as a student in autumn 1921 and retained an interest in the Neolithic standing stones throughout his career. According to the art historian Andrew Causey, Moore revisited Stonehenge on more than one occasion in the 1950s ‘when his daughter, Mary, was at school nearby’.19 Moore’s interest in Stonehenge culminated in a series of lithographs depicting the standing stones made in 1972–3 (Tate P02169– P02187). As the art historian Sam Smiles has outlined, by the 1930s a number of artists within Moore’s circle had developed an appeal for the standing stones, considering them to be examples of ancient British ‘primitive art’.20 Moore’s friend and artistic collaborator Paul Nash, for example, assimilated Britain’s prehistoric monuments into his modernist vocabulary, as seen in the painting Equivalents for the Megaliths 1935 (Tate T01251). In a letter to Nash written on 15 September 1933 Moore responded to a query stating, ‘Yes. I’ve seen Stonehenge. Its [sic] very impressive. I’ve read somewhere that certain primitive peoples coming across a large block of stone in their wanderings would worship it as a god – which is easy to understand, for there’s a sense of immense power about a large rough-shaped lump of rock or stone’.21 In their essay examining Moore’s outdoor sculptures, art historians Penelope Curtis and Fiona Russell suggested that ‘by the later 1930s Moore and Hepworth were clearly ready to suggest that their own sculptures were monuments in a lineage of stone monuments of the Neolithic builders, with perhaps a similarly arcane or forgotten purpose. Their sculptures were at once ancient and modern, or, to use the title of Paul Nash’s painting, Equivalents for the Megaliths’.22

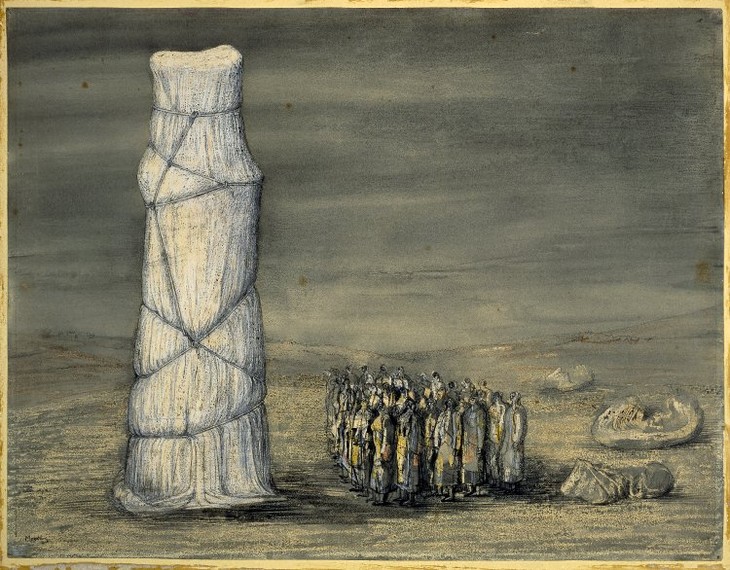

Henry Moore

Crowd Looking at a Tied-Up Object 1942

© Trustees of the British Museum; © The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.16

Henry Moore

Crowd Looking at a Tied-Up Object 1942

© Trustees of the British Museum; © The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Nupe men standing around two veiled Dako cult dance costumes, Nigeria. Image reproduced in Leo Frobenius, Kulturgeschichte Afrikas (1933)

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.17

Nupe men standing around two veiled Dako cult dance costumes, Nigeria. Image reproduced in Leo Frobenius, Kulturgeschichte Afrikas (1933)

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

During the Second World War, when a lack of available materials brought Moore’s sculptural activity to a near standstill, he made a number of drawings depicting a crowd of people gathered before a towering standing sculpture shrouded in fabric (fig.16). The curator Alan Wilkinson has asserted that ‘the source was almost certainly the photograph in [Leo] Frobenius’s Kulturgeschichte Afrikas (1933) showing a group of Nupe tribesmen from northern Nigeria standing around two veiled (but not tied-up) Dako cult dance costumes’ (fig.17).23 Moore owned a copy of Frobenius’s book and its reproductions served as the basis for several drawings he executed during the mid-1930s. According to Wilkinson, Crowd Looking at a Tied-Up Object was ‘undoubtedly Moore’s most famous pictorial drawing’, and had ‘Surrealistic overtones’.24 By the 1970s the critics Robert Melville and John Russell had both identified an affinity between the sculptural character of the upright motives and what they regarded as the surreal mood and content of his earlier drawing.25 Melville wrote:

A drawing of a Surrealist situation made by Moore in 1942, soon after completing the shelter drawings, proved to be in some measure prophetic. It obviously connected with his desire to resume his sculptural activities, which were suspended when he was engaged as a war artist, and is conceived in terms of an enigmatic promise ... One could now easily be convinced that the wrappings hide a version of one of the Upright Motives of 1955–56.26

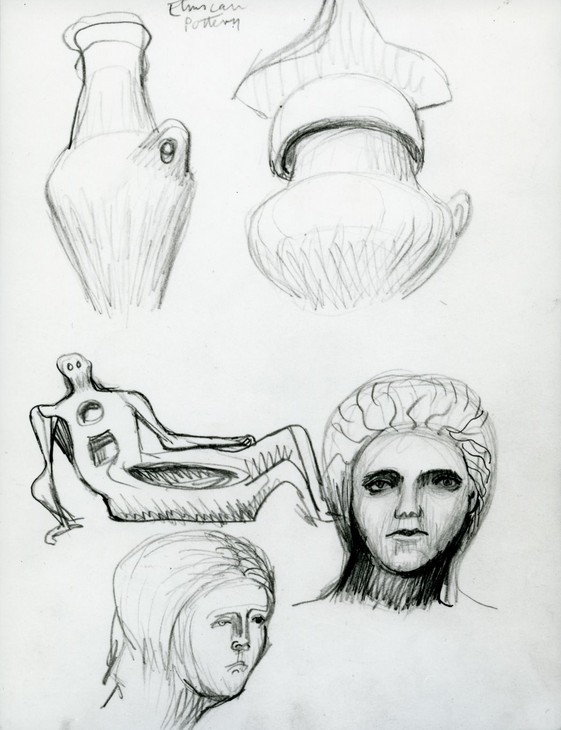

Henry Moore

Etruscan Pottery and Heads 1955–6

Graphite, pen and ink on paper

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.18

Henry Moore

Etruscan Pottery and Heads 1955–6

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

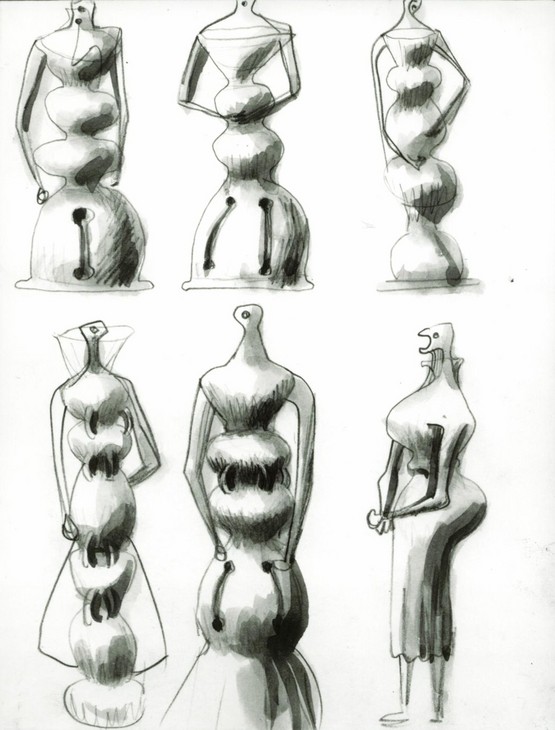

Henry Moore

Six Standing Forms 1955–56

Graphite, brush and ink on paper

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.19

Henry Moore

Six Standing Forms 1955–56

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The origins of the bulbous form halfway up Upright Motive No.7 and the circular indentations in its surface may be traced to works made by Moore following his first and only visit to Greece in February 1951. On his return home Moore made a sketch of two vases or urns, annotated with the phrase ‘Etruscan Pottery’ (fig.18). These rounded containers then formed the basis of a series of drawings depicting segmented female figures (fig.19). In addition to the similarities between these figures and Upright Motive No.7 in terms of their construction – in distinct units, conjoined by smooth curves – affinities can also be identified in their decoration. The three evenly spaced holes encircling the swollen midriff of one figure (fig.19), which have been drawn to give the impression that they have been cut out from a solid mass, resemble in their appearance and placement the circular depressions made in the surface of Upright Motive No.7. Although Moore did not sign or date these sketches they have been retrospectively dated 1955–6. However, the cataloguer of Moore’s drawings Ann Garrould noted in 2003 that the other contents of the notebook in which these sketches were made indicates that ‘the notebook was started well before 1955’.27

Henry Moore

Wall Relief: Maquette No.2 1955

Bronze

180 x 337 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Darren Chung, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.20

Henry Moore

Wall Relief: Maquette No.2 1955

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Darren Chung, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The final work for the Bouwcentrum in Rotterdam was constructed in brick and comprised rounded, organic shapes framed by vertical striations on both sides and geometric blocks above and below. According to John Russell, Moore’s relief works were, ‘abstract arrangements that had a formal life of their own: a vigorous, chunky, all-purpose vitality that seemed to burst out of the columnar structure and set off all manner of associations. They were not so much reliefs as free-standing sculptures that seemed to have sunk into the body of the wall’.30 Following a discussion with Moore on 12 December 1980, Tate curator Richard Morphet reported that the Bouwcentrum commission ‘led to the idea of releasing the forms from their incorporation in the fabric of the wall so that they become free-standing’.31

Grouping the Upright Motives

Tate’s cast of Upright Motive No.7 was first exhibited in Moore’s solo exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, in 1960 where it was displayed in a grouping alongside Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross and Upright Motive No.2. Although each of the upright motives were conceived as individual artworks, Moore later suggested that the idea of presenting numbers one, two and seven together had come to him at an early stage in their development. In 1965 Moore claimed that ‘when I came to carry out some of these maquettes in their final full size, three of them grouped themselves together’. 32

Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60, and Upright Motive No.2 1955–6, cast c.1958–62 installed at the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller in Otterlo, 1965

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.21

Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60, and Upright Motive No.2 1955–6, cast c.1958–62 installed at the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller in Otterlo, 1965

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore’s sculptures may also be understood in relation to the engagement of religious themes and subjects by artists working at the same time. In 1965 a critic writing in the Burlington Magazine observed that Moore’s upright motives were created ‘at roughly the same time as Graham Sutherland was experimenting with the same type of figure in his paintings’.38 However, it was not until 1998 that this reference to the British painter Sutherland was explored further. In her book New Art / New World: British Art in Postwar Society the art historian Margaret Garlake compared Moore’s upright motives with contemporaneous works by Sutherland, remarking that the triptych of sculptures produced ‘a set of variations on natural forms that were congruent with Christian imagery in a manner comprable to Sutherland’s standing forms’.39 For example, in paintings such as Standing Forms II 1952 (Tate T03113; fig.22), Sutherland depicted three vertical forms comprised of interlocking organic shapes, some of which are positioned on plinths. These associations are strengthened by the fact that Moore knew Sutherland and his work well. Not only was he present at the unveiling of Sutherland’s Crucifixion 1946 at St Matthew’s Church in Northampton (which had also commissioned Moore’s Madonna and Child 1943–4), but he also exhibited alongside Sutherland in the British Pavilion at the 1952 Venice Biennale.

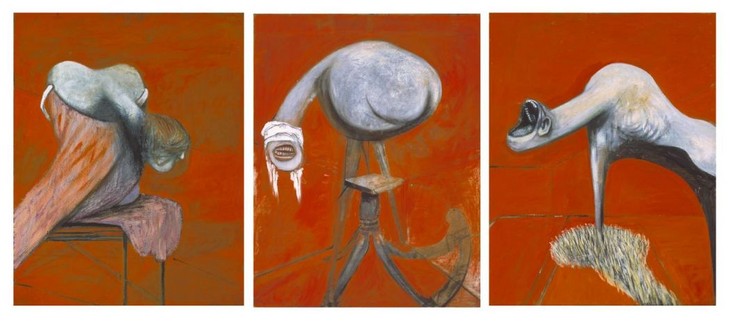

In addition to Sutherland, the paintings of Francis Bacon have also been thought to have influenced the forms that appear in Moore’s sculptures in the early to mid-1950s. In the catalogue for Moore’s posthumous exhibition at the Royal Academy, London, in 1988, the curator Susan Compton proposed that the bulbous torsos and truncated limbs of the figures in Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion c.1944 (Tate N06171; fig.23) bear a relation to Moore’s upright motives.40 Furthermore, the art historian Julian Stallabrass has observed that ‘from some points of view No.7 can be read as a figure with its head thrown right back and its open mouth pointed at the sky’ as though expressing the kind of extreme suffering depicted by Bacon (fig.24).41 It is probable that Moore viewed Bacon’s painting when it was acquired by Tate in 1953, when Moore was a trustee of the gallery. However, despite these connections Garlake concluded that ‘Moore’s work, like Sutherland’s, can more convincingly be located with a pastoral and holistic reading of nature than in the existentially oriented context of Bacon’s painting’.42

Detail of apex of Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.24

Detail of apex of Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate T02276

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

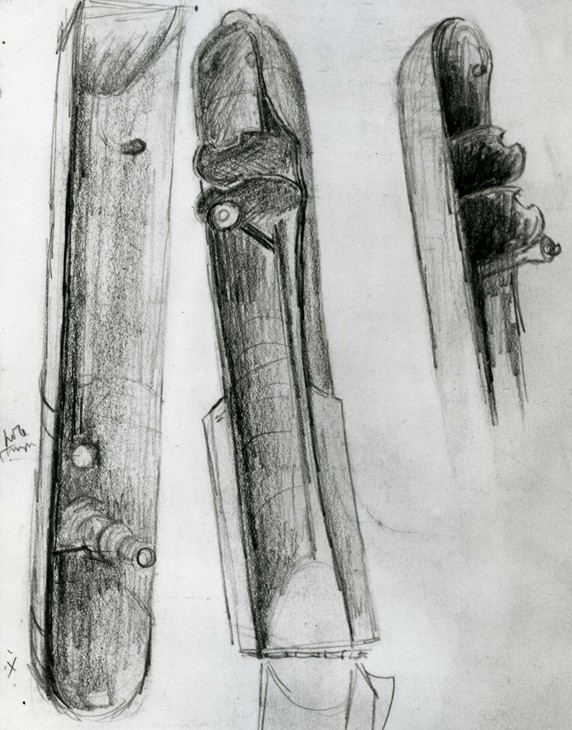

Moore’s work from the 1950s might nevertheless be viewed through the lens of post-war anxiety, as the work of Bacon and a younger generation of sculptors, including Lynn Chadwick and Reg Butler, have been previously. Stallabrass engaged one possible line of enquiry to this end with his claim that Moore’s sources for the upright motive series included a series of drawings he executed at the National Army Museum in 1941–2 (fig.25).43 Made while Moore was an Official War Artist, these drawings depict the internal workings of bombs. Their smooth outer casings contain complex mechanical workings, protrusions and taught wires that predate the rods and ribs visible in the upper section of Upright Motive No.7. For Stallabrass these drawings demonstrate that ‘the concerns of the upright motives are closer to Moore’s response to the war than to the ahistorical matters which solely primitive influences and associations would imply’.44

Henry Moore

Three Bomb Cases from an Army Museum 1943

Graphite and wax crayon on paper

210 x 165 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.25

Henry Moore

Three Bomb Cases from an Army Museum 1943

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

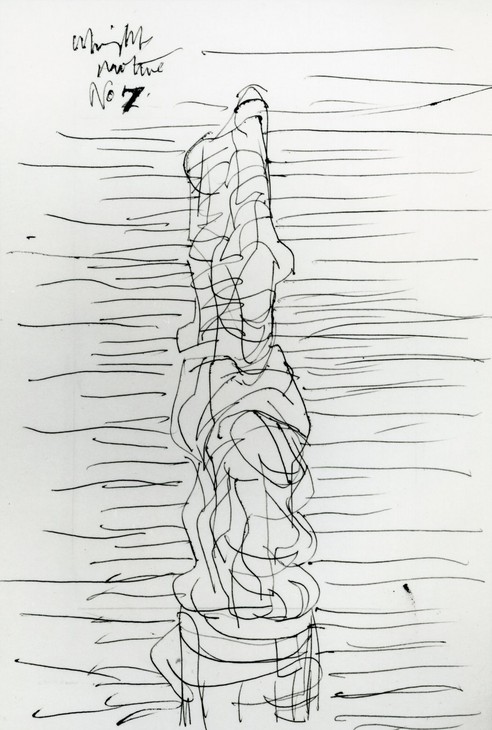

Henry Moore

Upright Motive No.7 c.1966

Ballpoint pen on paper

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.26

Henry Moore

Upright Motive No.7 c.1966

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In 1966 Moore returned to Upright Motive No.7 and created two drawings of the sculpture (see fig.26). It is unclear why Moore chose to revisit the sculpture at this particular time, but it is notable that in 1966–8 he also made an etching of Crowd Looking at a Tied-Up Object as part of a portfolio of prints entitled Meditations on the Effigy (see Tate P02079). The portfolio was published to mark the artist’s seventieth birthday and Robert Melville described the prints, which drew on earlier sketches and sculptures, as reflections on ‘a lifetime of creative enterprise’.45 It is possible that Moore had considered a graphic rendition of Upright Motive No.7 for the portfolio.

The Henry Moore Gift

Upright Motive No.7, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross and Upright Motive No.2 on display in the Duveen Galleries, Tate Gallery, London, 1978

Tate Archives

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.27

Upright Motive No.7, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross and Upright Motive No.2 on display in the Duveen Galleries, Tate Gallery, London, 1978

Tate Archives

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Following the exhibition the three upright motive sculptures were returned to Moore. In a letter to Moore’s secretary Betty Tinsley dated 25 July 1978, Ruth Rattenbury, Assistant Keeper of the Collection, itemised a number of works to be returned to the artist for repairs, and of the three upright motives noted that, ‘Mr Moore said that he would have them treated so that they were all the same colour’.49 In May 1979 the sculptures were returned to Tate and installed on a specially designed base on the lawn in front of the gallery. It is evident from the photographs taken of the installation at the time that the sculptures no longer displayed the variations in colour as they had previously (fig.28).

Upright Motive No.7, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross and Upright Motive No.2 installed on the front lawn, Tate Gallery, London

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.28

Upright Motive No.7, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross and Upright Motive No.2 installed on the front lawn, Tate Gallery, London

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

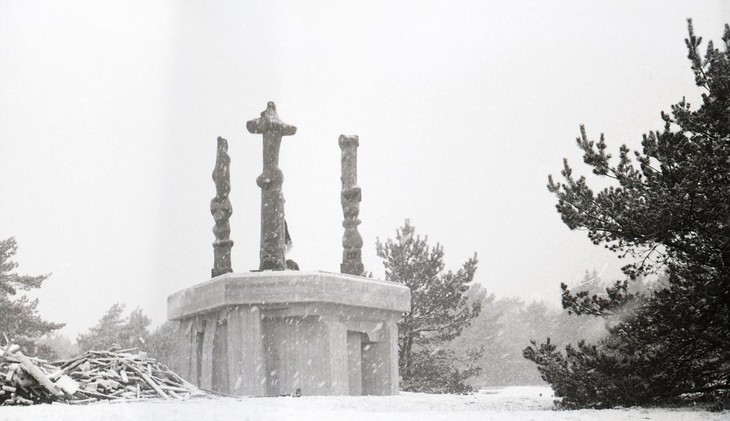

Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60, and Upright Motive No.2 1955–6, cast c.1958–62 installed at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, November 2013

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.29

Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60, and Upright Motive No.2 1955–6, cast c.1958–62 installed at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, November 2013

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

All three upright motive sculptures in the Tate collection remained on display on the Tate lawn until April 1983 when they were relocated to the nearby Battersea Park. On 26 May Tate was notified that vandals had breached the security fence surrounding the sculptures, which were still in the process of being installed, and had set fire to the protective canvas covering Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross and Upright Motive No.7. As a result the patina and surface of the lower areas of the two sculptures were charred.50 Despite this inauspicious start, the installation of the three upright motives continued as planned, and they were positioned in a prominent position on top of a raised incline. Apart from being removed temporarily for display at the Royal Academy of Arts and at Tate in 1988 and 1992 respectively, the sculptures remained at Battersea Park until October 1994. That month Upright Motive No.2 was forcefully rocked by vandals until it fell over and the decision was made to permanently remove all three of the upright motives from the park. They were subsequently placed on long-term loan to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in Wakefield (fig.29) although they were returned to Tate in 2003 and exhibited in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern for the display Henry Moore: Public Sculptures. In 2011 Upright Motive No.7 was displayed individually in the exhibition Single Form: The Body in Sculpture from Rodin to Hepworth in the Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain.51

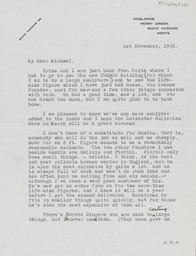

The five other bronze casts of Upright Motive No.7 are held in the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller in Otterlo, the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, the Henry Moore Foundation in Perry Green, and in a private collection.

Alice Correia

March 2013

Notes

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.160.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, broadcast BBC Radio, 14 July 1963, Tate Archive TGA 200816, p.18. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

Julie Summers, ‘Fragment of Maquette for King and Queen’, in Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, p.126.

For more information on the firm’s history see ‘H.H. Martyn & Co.’, in Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851–1951, http://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/organization.php?id=msib6_1232025346 , accessed 2 April 2013.

John Russell in Henry Moore, John Russell and A.M. Hammacher, Drie Staande Motieven, Otterlo 1965, unpaginated.

Henry Moore, Henry Moore at the British Museum, London 1981. In his introduction to the book Moore concluded that ‘It has been a wonderful experience for me to recapture the delight, the excitement, the inspiration I got in these pieces as a young and developing sculptor’ (p.16).

Sam Smiles, ‘Equivalents for the Megaliths: Prehistory and English Culture, 1920–50’, in David Peters Corbett, Ysanne Holt and Fiona Russell (eds.), The Geographies of Englishness: Landscape and the National Past 1880–1940, New Haven 2002, pp.199–223.

Penelope Curtis and Fiona Russell, ‘Henry Moore and the Post-War British Landscape: Monuments Ancient and Modern’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, p.138.

Anita Feldman Bennet, ‘Rediscovering Humanism’ in Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, p.69.

[Richard Calvocoressi], ‘T.2281, Three Motives Against Wall No.2’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.126.

Anon., ‘Acquisitions of Works of Art by Museums and Galleries: Supplement’, Burlington Magazine, vol.107, no.747, June 1965, p.338.

Margaret Garlake, New Art / New World: British Art in Postwar Society, New Haven and London 1998, p.191.

Julian Stallabrass, ‘Upright Motive No.5’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.247.

Robert Melville, ‘Henry Moore: Meditations on the Effigy’, in Henry Moore, Meditations on the Effigy, London 1968, pp.3–7.

These figures are based on those listed in a memo in the records for the exhibition. See Tate Public Records TG 92/344/2.

Related essays

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore and World Sculpture Dawn Ades

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www