Launching Moore’s International Career: Henry Moore at the Museum of Modern Art, New York 1946

Pauline Rose

Many commentators have suggested that Moore’s international career was launched when he won the sculpture prize at the Venice Biennale in 1948. This essay points to the importance of American interest in Moore in the 1930s and 1940s, in particular, his exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1946, the first solo exhibition there by a British artist.

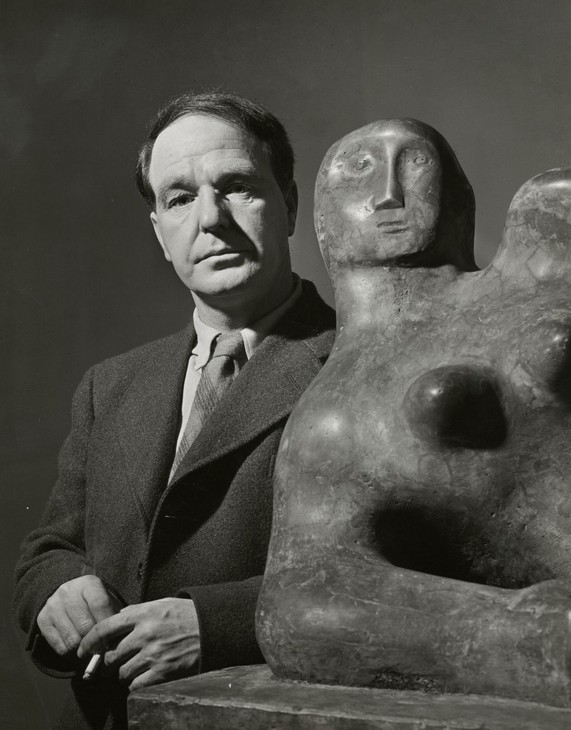

Many accounts of Henry Moore’s career imply that it was launched when he won the International Sculpture prize at the 1948 Venice Biennale. In reality, the momentum began with exhibitions in New York in the 1930s (one reviewer described Moore in 1935 as England’s ‘white hope in the field of sculpture, and justifiably so’),1 and 1940s. The culmination of these early successes was an exhibition of Moore’s work held at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1946 that travelled with great success to Chicago and San Francisco. Moore himself firmly believed that this recognition in America was instrumental in his winning the Venice prize, later observing: ‘I doubt that one would have won ... without the real groundwork and ... impetus that The Museum of Modern Art retrospective provided ... Now ... a good three-quarters of my work is in America.’2 Crucial to his success in New York, he felt, had been his early connections with his New York dealer Curt Valentin and key figures in the museum world, Alfred Barr, MoMA’s Director between 1929 and 1941 and holder of various posts at the museum for the rest of his career, and James Johnson Sweeney, a curator at the museum between 1935 and 1946.3

Curt Valentin first acted for Moore during the war years. In 1943 he showed in his Bucholz Gallery, as it was then known, some drawings by Moore that had been dispatched by diplomatic courier under the auspices of the British Council (although it did not have an official remit in the United State, it was still able to offer this practical support for the sculptor during the war).4 Reviews of the exhibition were mainly positive if somewhat florid in their attempted witticisms. In Art Digest it was noted that Moore had not yet received the same attention in the United States as, for example, Picasso: ‘England has not added a leaf to the flowering tree for so long, one forgets to look for foliation from that direction.’5 An article by Henry McBride reflected a common unease when dealing with abstract modern art:

It’s a bit of a test for the Entente Cordiale ... for Mr. Moore is British and we all, naturally, wish to love British art, but Mr. Moore is also abstract. This is not a test for me ... I hasten to add, for I got used to abstract art long ago, but it is for you, Mr. Average Citizen. The average citizen in this country refuses to take abstract art seriously. But ... with a war going on, we really ought to make an effort. It’s all the easier because ... Mr. Moore is not quite abstract. You can tell, partly, what some of the drawings are about ... All this is accomplished in admirable taste. Good taste is Mr. Moore’s middle name. It is his chief asset... Picasso, on the other hand, is not much noted for good taste ... When he is at his best, even I ... am as much repelled as pleased by the reverberations from his thunderbolts. Mr. Moore is much more discreet. He does not hurl thunderbolts ... That is the English [sic] of it, I suppose. It is gentlemanly.6

In 1945 James Thrall Soby, who held several posts at MoMA, including Director of the Department of Painting and Sculpture, wrote the catalogue introduction for an exhibition of Moore’s drawings held at Valentin’s gallery, describing the artist as one of the greatest contemporary sculptors and a leader of the current renaissance in British art.7 By this point, Valentin was recognised as a champion of modern sculpture in America.8 According to Jane Wade, who helped run Valentin’s gallery after his death in 1954, Valentin’s enthusiasm and commitment to the field enabled him to take the risk of trying to promote sculpture ‘not only for the marble halls of the museums but for the private home – a concept practically unknown before Curt.’9

Curt Valentin (left) with Henry Moore in the artist's Top Studio, Perry Green c.1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Curt Valentin (left) with Henry Moore in the artist's Top Studio, Perry Green c.1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Alfred Barr first heard of Moore in 1927 through a curator at the Victoria & Albert Museum.12 It is not known when he first met Moore but his visits to Moore’s studio in the 1930s meant a great deal to the sculptor who felt that they compensated for some of the negative responses to his work in England.13 Barr included Moore’s Two Forms 1934 in his landmark exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art of 1936, and helped ensure that the piece was subsequently bought by MoMA. In his catalogue Barr presented Moore as participating actively in international abstraction and placed him in the category of ‘non-geometrical’, or biomorphic, abstraction.14 He also included a small lead Reclining Figure 1932 in Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism later that year, noting that Moore was ‘influenced by Arp and Picasso’.15 Moore was also represented in the museum’s 1939 Art in Our Time exhibition, which coincided with the New York World’s Fair. The catalogue in Moore’s library at Perry Green is warmly inscribed by Barr with the words, ‘For Henry Moore. With many thanks for the loan of his two fine pieces. Alfred Barr.’

It seems to have been James Johnson Sweeney who wrote to Moore to propose a major solo exhibition at MoMA: it was to be, as he later described it, the largest show for a living British artist ever held in America (figs.2 and 3).16 The catalogue contained quotes from Philip Hendy and Herbert Read, important English supporters of the sculptor, and Sweeney described Moore as an artist of ‘courage ... personal sympathy, humility and integrity.’17

The artist Stanley William Hayter, an unidentified man, the book-seller and publisher Anton Zwemmer and curator René d'Harnoncourt (left to right) with Reclining Figure 1932 by Moore, during the exhibition Henry Moore at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, July 1946.

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

The artist Stanley William Hayter, an unidentified man, the book-seller and publisher Anton Zwemmer and curator René d'Harnoncourt (left to right) with Reclining Figure 1932 by Moore, during the exhibition Henry Moore at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, July 1946.

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore next to Reclining Figure 1932 in Henry Moore at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1946, published in 'British Sculptor Henry Moore Shocks and Pleases in his First Big Exhibit in U.S.', Life, 20 January 1947

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Eliot Elisofon for Life, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Moore next to Reclining Figure 1932 in Henry Moore at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1946, published in 'British Sculptor Henry Moore Shocks and Pleases in his First Big Exhibit in U.S.', Life, 20 January 1947

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Eliot Elisofon for Life, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore himself proved a great hit with the museum staff and the press. In January 1947 Monroe Wheeler, Director of Exhibitions and a Trustee of MoMA, informed Moore that attendance figures were running much higher than those for a major Chagall exhibition a year previously and that it had been ‘an inspiration and pleasure’ to have him as their guest: he had been ‘loved by everyone’ he met.18 After the exhibition the curator René d’Harnoncourt told Moore that everybody was still talking about him and they were missing him: ‘I can honestly say that I have never seen anyone make so many friends in so short a time.’19

Journalists particularly liked Moore’s direct and down-to-earth approach when talking about his work. Henry McBride noted the appeal to the public of Moore’s own words as they appeared on information panels at the MoMA exhibition: ‘he knows how to write, and he probably knows how to talk.’20 The New York Times suggested that the use of Moore’s own words in the exhibition would ‘make less baffling the average spectator’s task of appreciation.’21 Frequently the man himself appeared to interest American audiences just as much as his work. In Life magazine the sculptor was described as ‘soft-spoken but highly articulate ... short, brown-haired, tweedy and married’ (see fig.3).22The New Yorker described Moore as ‘a short, alert, friendly man of forty-eight, with a ruddy face and an easy conversational style.’23 Elsewhere it was observed that he was ‘a man of middle size with ... regular features and flat silky hair.’24

Reviews of the show explicitly linked Moore and his work to contemporary American perceptions of Britain and the British. Cultural stereotypes abounded with an article in Art Digest referring to Moore’s influences from a variety of cultures: ‘a sprinkle of salt and pepper on a dish indigenous to Britain long before roast beef and suet pudding. Beneath the surface ... is a force elemental and universal on one hand, and frighteningly a part of the primeval history of that tight little island at the same time.’25 The magazine also linked Moore’s success with the endurance shown by the British during the Second World War: ‘It has been said that England loses every battle except the last. Could it be that Henry Moore personifies his country’s El Alamein in the history of modern art expression, which was originally conceived from the brushes of Constable and Turner?’ A second article in Art Digest compared Moore positively with Picasso:

There is more aesthetic vitality in a single drawing by Henry Moore at the Modern Museum than in the entire crop of post-war Picassos now exciting controversy in New York. Age and success appears to have banked the fire of Picasso’s periods. Beautifully installed, the Henry Moore exhibition provides a tangible thrill to all who vibrate to the strains of modern design and the entire concept of art constructed as an architect builds a building. When it comes to the validity of modernism as an artistic outlet in an age faced by mechanical tyranny, the response to the Moore show can only be, ‘This is it!’26

In Art in America it was claimed that Moore’s achievements were due to his maintaining his own artistic direction and not compromising in order to suit public taste. Other English artists, it was argued, had evident ability and promise but had fallen victim to both institutional patronage and popular success and in the process had lost their artistic independence.27

Subsequently, explicit links were made between Moore’s work and the values for which the two countries had fought during the Second World War. Four of Moore’s sculptures were included in the 1948 exhibition at MoMA called Painting and Sculpture in the Museum of Modern Art. In the catalogue it was argued that the museum and its collection had played a crucial role during the war in protecting America’s cultural life, its economy and political structures. Representing the work of artists from many countries, the collection could be positioned as symbolic of both individual freedom as well as the freedom of nations to place value on the artistic products of diverse cultures, and a means through which to encourage positive international relationships. In particular, Alfred Barr argued that art could help defeat the ‘international hatred against which we are now fighting on the field of battle.’28 The conflation of Moore’s work with not just Western European countries but also American values and ambitions would become central to the analysis and presentation of his sculptures in the period of the Cold War.

Some negative voices were raised in the 1940s and 1950s. Reviewing Moore’s exhibition at MoMA Clement Greenberg believed that Moore’s work was making ‘an exaggerated impression’ and that it answered ‘too perfectly the current notion of how modern sophisticated and inventive sculpture should look’. In 1947, however, Greenberg did allow that Moore was in possession of ‘no mean talent’29 and in a 1965 essay his negativity appears to have lessened quite considerably when he wrote, ‘A grand, sublime manner has been a peculiarly English aspiration since the eighteenth century. Henry Moore and Francis Bacon are possessed by it in their separate ways.’30 Writing for Art News in December 1954 Thomas Hess argued that Moore had been flattered into undertaking architectural commissions that were ‘far beyond the capacities of his dainty, eclectic style and his neat but limiting concepts of the work of art.’31 However, such criticisms were few.

Reflecting later on Moore’s reception in the United States in the post-war period James Johnson Sweeney suggested that the sculptor’s nationality was the key to his success in America: ‘At the time of the Moore show here (at MoMA), he was still some sort of avant-garde figure ... But he was an Englishman ... Englishmen give an impression of conservative experimentation when they are being experimental.’32 It is clear that through the initial support from Curt Valentin and later from MoMA personnel, New York was pivotal to the establishment of Moore’s international reputation as somehow both modernist and ‘old world’, and so acceptable, for a period, to unusually broad swathes of the public.

Notes

Henry McBride, ‘The Henry Moore Drawings’, New York Sun, 14 May 1943, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Curt Valentin, letter to Henry Moore, 26 November 1951, Curt Valentin Papers, Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, III.A.20.

Henry McBride, ‘Four Transoceanic Reputations’, Art News, January 1951, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Alfred Barr, letter to Donald Hall, 22 January 1964, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., roll 2187.

Catalogue note, Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1936, p.256.

Seldis 1973, p.53, and James Johnson Sweeney, untitled interview with Henry Moore in Partisan Review, vol.14, no.2, March–April 1947, pp.180–5.

Monroe Wheeler, letter to Henry Moore, 22 January 1947, Museum of Modern Art Archive, New York, Registrar Exhibition Files Exh.#339.

René d’Harnoncourt, letter to Henry Moore, 18 February 1947, Museum of Modern Art Archive, New York, Registrar Exhibition Files Exh.#339.

Henry McBride, ‘Henry Moore, Modernist’, New York Sun, 20 December 1946, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Edward Alden Jewell, ‘Art Show Offers Display by Moore’, New York Times, 18 December 1946, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

‘British Sculptor: Henry Moore Shocks and Pleases in his First Big Exhibit in U.S.’, Life, vol.22, no.3, 20 January 1947, pp.77–80.

W. Rogers, ‘Sculptor Henry Moore Opening Show Tuesday’, Norfolk Virginian Pilot, 15 December 1946, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

‘Henry Moore, Modern Briton, Impresses with his Aesthetic Vitality’, Art Digest, 1 January 1947, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

‘Moore, Vital Briton’, Art Digest, 15 February 1947, Henry Moore Foundation Archive. The references to modern design and to architecture here are worth noting, given the ways whereby Moore’s sculptures would later become such a feature of the American urban landscape

Gigi Richter, ‘Introduction to Henry Moore’, Art in America, vol.35, no.1, January 1947, pp.5 and 16.

Acknowledgements

This essay draws on material in Pauline Rose, Henry Moore in America: Art, Business and the Special Relationship, London 2014.

Dr Pauline Rose is Professor of Art History at the Arts University Bournemouth.

How to cite

Pauline Rose, ‘Launching Moore’s International Career: Henry Moore at the Museum of Modern Art, New York 1946’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www