Joseph Mallord William Turner Note on Poetry and Painting (Inscriptions by Turner) 1809-11

Joseph Mallord William Turner,

Note on Poetry and Painting (Inscriptions by Turner)

1809-11

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

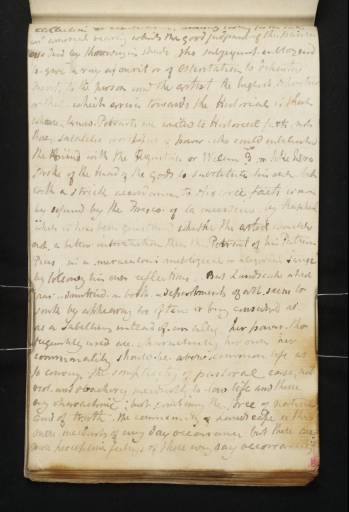

Folio 45 Verso:

Note on Poetry and Painting (Inscriptions by Turner) 1809–11

D07591

Turner Bequest CX 45a

Turner Bequest CX 45a

Inscribed by Turner in ink (see main catalogue entry) on white laid paper, 185 x 116 mm

Stamped in black ‘CX 45a’ bottom right, running vertically

Stamped in black ‘CX 45a’ bottom right, running vertically

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

References

1909

A.J. Finberg, A Complete Inventory of the Drawings of the Turner Bequest, London 1909, vol.I, p.294, CX 45a.

1990

Andrew Wilton and Rosalind Mallord Turner, Painting and Poetry: Turner’s ‘Verse Book’ and his Work of 1804–1812, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1990, pp.85–6, 136.

recollection or consideration, anxiously looking for the date | on armorial bearing which the good judgment of the painter | offended by throwing in shade, tho subsequent emblazoned | to give a ray of sunset or of ostentation to departing | spirit of the person and the artist the highest department | or that which arrives towards the Historical is that | where Landsc[ape] Portraits are united to Historical facts, not | those ..., worshipers of know[ledge]. Who could ......| the Ruins with the Augustus. Or Wilson ? or like Nero | strike of[f] the Head of the Gods to substitute his own. but | with a strict accordance to Historic facts is own | by ... the Fresco of la incendio by Raphael | which it has been questioned whether the artist wanted | not a better introduction than the Portrait of his Patron | Pius in a miraculous mythological or allegorical image | by following his own reflections. But Landscape which | was admitted in both departments of art seems to | sink by appearing too often or being considered | as a rebelling instead of an ally her power tho | frequently used are characteristically her own her | commonality should be above common life as | to convey the simplicity of pastoral ease, not | riot and debauchery incidental to low life and then | by characteristic; but combining the force of nature | and of truth . the community of landscape is thus | more ... of everyday occurance but where there are | more perceptive feelings of these everyday occurrances...[continued on folio 44 verso]...by one more than the other who has the book | of nature before his view with the words of the Poet of the Seasons

“To one be ever Nature’s volume be displayd

and happy to catch my inspirations theme

thankly some passage enraptured to translate”

but the translation will be a different tho drawn from | the same plank of nature as the pursuits study and | various conception and perception of that passage | combining the rules and beauties of words to the Poet | the unity of contending principles that may or may not | meet the impression to be delineated by the Painter than | drawing from the same source. Their sentiments contrast | professing of fullness of character and expression which | is delineation in one and description in the other, their | sentiments being frequently the same. Other their arts | require a very different way to elucidate their senti | ments, have given by long acceptance that the | Painters utmost need is to be poetical, follow the | Poet and define his descriptions. But his descriptions are | frequently above the Painters power and expression color | and line in description which is his delineation has such | merit must be drawn from attributes but the Painter | must be governed by sentiments contained in the | transcription of some happy, fleeting passage surpassing | all description and yet if the Painter succeeds he | is poetical “is conceived in true Poetic vein” but suffers no conception but his own perception thus regularly | combined, reproduces and expresses that which he cannot | express by words ... more the Poet could discover the colour | [continued on folio 43 verso] of his art without disturbing upon, those pursuits are | different tho they love and follow the same course | and have a mutual regard in admiration

“To one be ever Nature’s volume be displayd

and happy to catch my inspirations theme

thankly some passage enraptured to translate”

but the translation will be a different tho drawn from | the same plank of nature as the pursuits study and | various conception and perception of that passage | combining the rules and beauties of words to the Poet | the unity of contending principles that may or may not | meet the impression to be delineated by the Painter than | drawing from the same source. Their sentiments contrast | professing of fullness of character and expression which | is delineation in one and description in the other, their | sentiments being frequently the same. Other their arts | require a very different way to elucidate their senti | ments, have given by long acceptance that the | Painters utmost need is to be poetical, follow the | Poet and define his descriptions. But his descriptions are | frequently above the Painters power and expression color | and line in description which is his delineation has such | merit must be drawn from attributes but the Painter | must be governed by sentiments contained in the | transcription of some happy, fleeting passage surpassing | all description and yet if the Painter succeeds he | is poetical “is conceived in true Poetic vein” but suffers no conception but his own perception thus regularly | combined, reproduces and expresses that which he cannot | express by words ... more the Poet could discover the colour | [continued on folio 43 verso] of his art without disturbing upon, those pursuits are | different tho they love and follow the same course | and have a mutual regard in admiration

Turner defends the relative status of painting, and then of landscape, comparing it with history painting which his generation had been taught to regard as the highest expression of the art, and portraiture; the latter comparison is perhaps an own-goal since promoters of landscape usually argued that it is more than an imitative art. Turner seems to refer to the landscape painter Richard Wilson, whom Joshua Reynolds, in his Royal Academy Discourses, had censured for ‘introducing gods and goddesses, ideal beings, into scenes which were by no means prepared to receive such personages’, being ‘too near common nature’.1 By ‘la incendio by Raphael’ Turner means The Fire in the Borgo painted by Raphael’s studio in the Stanze dell’Incendio in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican, Rome.

In this passage as a whole, Turner seems mainly concerned to defend landscape from comparison with low genres; by the ‘riot and debauchery incidental to low life’ he evokes not just a debased picture of common life but paintings by Netherlandish artists like David Teniers and Isaak van Ostade who specialised in such scenes. As an example of the ‘more perceptive feelings’ of those who have ‘the book of nature’ before them, he misquotes ‘the Poet of the Seasons’, James Thomson (author of The Seasons, 1730), and considers the response of painter and poet as one of ‘translation’ – ‘delineation in one and description in the other, their sentiments being frequently the same’. While painters aspire to be ‘Poetical’, their ideas must be ‘contained in the transcripts of one happy, fleeting passage surpassing all description’. More coherent and presumably later observations on the relationship between poetry and painting, in which Turner again refers to Thomson, are in the Perspective sketchbook (Tate D07448–D07438; Turner Bequest CVIII 53a–48a).

Notes like these were generally written as Turner collected ideas for his lectures as Professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy, in which he intended to range far beyond their immediate subject. This passage is written in ink, not used elsewhere in the book. It could be contemporary, or a later addition prompted by looking through its contents; Turner continued to make notes for the lectures and then revised them up to 1811. His thoughts here on the ‘fleeting passage’ may have a particular bearing on the drawings of landscape and sky in this book, which while depicting transient effects are sometimes given quite elaborate inscriptions ranging from colour notes to almost poetic descriptions. One example is the landscape on folio 7 (D07545) whose setting, perhaps the River Derwent at Isel, inspired a particularly delicious pastoral idyll, bright with ripe corn and sparkling water. Another is the sunset on folios 39 verso–40 (D07582–D07583) where sky colours are likened to ‘Blood’ or clouds and smoke compared.

Verso:

Blank

David Blayney Brown

August 2009

How to cite

David Blayney Brown, ‘Note on Poetry and Painting (Inscriptions by Turner) 1809–11 by Joseph Mallord William Turner’, catalogue entry, August 2009, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www