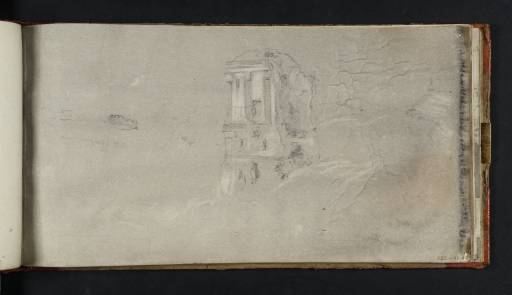

Joseph Mallord William Turner The So-Called Sedia del Diavolo, Rome 1819

Image 1 of 2

Joseph Mallord William Turner,

The So-Called Sedia del Diavolo, Rome

1819

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Folio 43 Recto:

The So-Called Sedia del Diavolo, Rome 1819

D16463

Turner Bequest CXC 48

Turner Bequest CXC 48

Pencil and grey watercolour wash on white wove paper, 130 x 255 mm

Inscribed by ?John Ruskin with traces of red ink top right and by unknown hands in pencil ‘51’ top right and ‘48’ bottom right

Stamped in black ‘CXC 48’ bottom right

Stamped in black ‘CXC 48’ bottom right

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

References

1909

A.J. Finberg, A Complete Inventory of the Drawings of the Turner Bequest, London 1909, vol.I, p.566, as ‘Another view of same fragment.[see CXC 47]’.

1983

Cecilia Powell, ‘Turner’s Vignettes and the Making of Rogers’ “Italy” ’, Turner Studies, vol.3, no.1, Summer 1983, p.7.

1984

Cecilia Powell, ‘Turner on Classic Ground: His Visits to Central and Southern Italy and Related Paintings and Drawings’, unpublished Ph.D thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London 1984, pp.285 note 69, 355–6 note 32, 428, as ‘Ruin in the Campagna – the so-called Temple of Salus (cf. Piranesi’s view of the same ruin, Hind, no. 71; also Turner’s illustration for Rogers’ Italy: W, no. 1168)’.

1987

Cecilia Powell, Turner in the South: Rome, Naples, Florence, New Haven and London 1987, pp.135 note 110, 170 note 14.

1993

Dr Jan Piggott, Turner’s Vignettes, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1993, p.82 no.5.

In addition to the great monuments and buildings of central Rome, Turner recorded a number of noted landmarks found in the northern outskirts of the city such as the Fontana dell’Acqua Acetosa (see the Naples: Rome C. Studies sketchbook, Tate D16138; Turner Bequest CLXXXVII 50), the Torre Lazzaroni (see folio 27, D16442; Turner Bequest CXC 32) and the Ponte Molle (see folio 53, D16475; Turner Bequest CXC 59). The subject of this sketch is the so-called Sedia del Diavolo (Devil’s Chair), a Roman tomb dating from the second or third century which stands in present-day Piazza Callistio, near to the ancient Via Nomentana.1 The brick structure, known today as the tomb of Elio Callistio, is comprised of two storeys and derives its names from the shape suggested by its three surviving walls.2 Its ruined appearance, perched on an area of high ground between the Ponte Nomentano and the Church of Sant’Agnese fuori le mura, represented a picturesque motif for topographical artists.3 Turner made a number of studies around the tomb, documenting its appearance from a variety of angles, see folios 1, 25 verso, 26 verso, 39 and 42 (D16399, D16426, D16428, D16458 and D16462; Turner Bequest CXC 5, 22a, 23a, 44 and 47). He also recorded its location in relation to the Ponte Nomentano, see folios 24 verso and 45 (D16424 and D16465; Turner Bequest CXC 21a and 50). This composition depicts the structure from the south, showing the crumbling walls of the outer façade with a view through to the interior. The angle of the view is very close to that depicted by the eighteenth-century Welsh landscape artist, Richard Wilson (1713–1782) in a number of paintings, see for example Strada Nomentana circa 1765–70 (Tate, N00301).4 It is also repeated in a contemporary oil sketch by the Austrian artist, Heinrich Reinhold (1788–1825), The Roman Campagna, with Mount Soracte 1819–24 (Kunsthalle, Hamburg).5 Like many drawings within this sketchbook, the study has been executed over a washed grey background and Turner has lifted or rubbed through to the paper beneath to create white highlights.

The sketch was previously identified by Cecilia Powell as the so-called Temple of Salus, a Roman funerary monument which appears in an etching by Piranesi, Tempio antico volgarmente detto della Salute [Ancient Temple popularly known as Temple of Salus] 1763, from the Vedute di Roma (1748–1778).6 However, this latter tomb, which stands on the Via Appia Nuova, approximately one mile from the junction with the Via Appia Pignatelli, is characterised by a decorative frieze of bas-reliefs beneath the capitals of the Corinthian pilasters and does not have the doorway or window openings visible in Turner’s drawing.7 It also stands on a flat area of land rather than the small hillock clearly shown. Both Powell and Jan Piggott have argued that it is the same ruin featured in Turner’s vignette, Campagna of Rome circa 1827, for Rogers’s Italy (see Tate D27678; CCLXXX 161).8 The re-identification of this and other sketches in the Small Roman C. Studies sketchbook as the Sedia del Diavolo leads to the conclusion that it must be this ruin, not the Temple of Salus, which appears in the watercolour. The choice of landmark may have been inspired by Rogers’s lines, ‘An empty tomb, a fragment like the limb | of some dismembered giant’, re-calling the popular notion that the Sedia del Diavolo was a vast chair used by the Devil.9 In common with many of the vignette illustrations for Rogers’s Italy, Turner has fabricated the scene using composite details from different landmarks. He has represented the structure on level, not hilly terrain, and has placed it in the vicinity of the imagined remains of an aqueduct.

Touring club italiano, Roma e Dintorni, 6th edition, Milan 1977, p.319; and Raymond Keaveney, Views of Rome from the Thomas Ashby Collection in the Vatican Library, exhibition catalogue, Smithsonian Institution, Washington 1988, p.242.

See photographs in Oreste Ferrari, Tea Marintelli, Valerie Scott et al., Thomas Ashby: Un Archeologo Fotografa la Campagna Romana Tra ’800 e’900, Rome 1986, p.32, no.10 figs. 1–4. See also the on-line photographic archive of Antonio Cederna (1921–1996), http://archivio.archiviocederna.it/xSearch/?query=sedia+del+diavolo , accessed June 2009.

See for example a drawing attributed to Jacques-Françoise Amand (1730–69), reproduced in Keaveney 1988, no.66, p.243.

See also Strada Nomentana, (Tate, N04511), Classical Landscape with Venus and Adonis circa 1754–5 (Victoria and Albert Museum) and View on the Via Nomentana circa 1766 (Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum, Bournemouth), reproduced in David Solkin, Richard Wilson, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1982, nos.70 and 123.

See Peter Galassi, Corot in Italy: Open-Air Painting and the Classical-Landscape Tradition, New Haven and London 1991, p.121, reproduced fig.148.

Verso:

Blank except for traces of grey watercolour

Blank except for traces of grey watercolour

Nicola Moorby

June 2009

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘The So-Called Sedia del Diavolo, Rome 1819 by Joseph Mallord William Turner’, catalogue entry, June 2009, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www