Joseph Mallord William Turner Verses (Inscription by Turner) c.1806

Image 1 of 2

Joseph Mallord William Turner,

Verses (Inscription by Turner)

c.1806

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

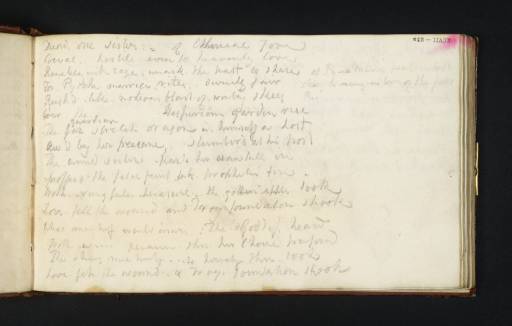

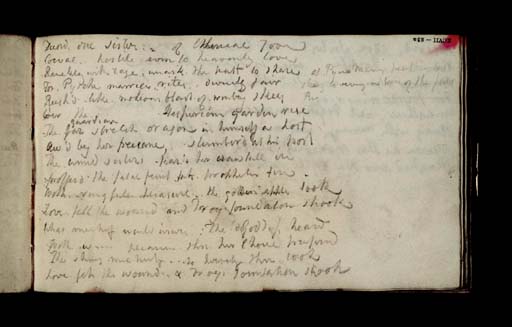

Folio 83 Verso:

Verses (Inscription by Turner) circa 1806

D06165

Turner Bequest XCVII 83a

Turner Bequest XCVII 83a

Inscribed by Turner in pencil (see main catalogue entry) on white wove paper, 107 x 182 mm

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

References

1909

A.J. Finberg, A Complete Inventory of the Drawings of the Turner Bequest, London 1909, vol.I, p.252, XCVII 83a.

1984

Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, revised ed., New Haven and London 1984, p.45.

1990

Kathleen Nicholson, Turner’s Classical Landscapes: Myth and Meaning, Princeton 1990, pp.78, 87 note 7.

1990

Andrew Wilton and Rosalind Mallord Turner, Painting and Poetry; Turner’s ‘Verse Book’ and his Work of 1804–1812, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1990, p.155.

Written with the sketchbook inverted. Only partly published by Finberg, Turner’s verses were transcribed in full by Rosalind Mallord Turner, whose reading is followed here:

Discord dire Sister of Ethereal Jove

Coeval hostile even to heavenly love

Ranckling with rage, unask[ed] the feast to share

For Psyche marriage rites divinly fair

Rush’d like noxious blast of wintry skies

O’er the [guardian] Hesperian garden rise

The far stretch dragon in himself a host

Aw’d by her presence, slumber’d at his post

The timid sisters, fear’d her vengfull ire

Profferd the fatal fruit & ate prophetic fire

With wrongful pleasure, the golden apple took

Love felt the wound and Troy’s foundation shook

What mischief would insue; The Goddess heard

With warm pleasure then her choice preferred

The shiny mischief so wisely thou took

Love felt the wound &Troys foundations shook

[written at side of page]

At Psyche marriage feast to share striving to

Revenge our love of the fair

Coeval hostile even to heavenly love

Ranckling with rage, unask[ed] the feast to share

For Psyche marriage rites divinly fair

Rush’d like noxious blast of wintry skies

O’er the [guardian] Hesperian garden rise

The far stretch dragon in himself a host

Aw’d by her presence, slumber’d at his post

The timid sisters, fear’d her vengfull ire

Profferd the fatal fruit & ate prophetic fire

With wrongful pleasure, the golden apple took

Love felt the wound and Troy’s foundation shook

What mischief would insue; The Goddess heard

With warm pleasure then her choice preferred

The shiny mischief so wisely thou took

Love felt the wound &Troys foundations shook

[written at side of page]

At Psyche marriage feast to share striving to

Revenge our love of the fair

Discord dire sister of Etherial Jove

Coeval hostile even to heavenly love

Unasked at Psyche’s bridal feast to share

Mad with neglect and envious of the fair

Fierce as the noxious blast thou cleav’d the skies

And sought the Hesperian garden golden prize

Coeval hostile even to heavenly love

Unasked at Psyche’s bridal feast to share

Mad with neglect and envious of the fair

Fierce as the noxious blast thou cleav’d the skies

And sought the Hesperian garden golden prize

The Guardian Dragon in himself an host

Aw’d by thy presence slumber’d at his post

With vengeful pleasure pleas’d the Goddess heard

Of future woes and then her choice preferred

The shiny mischief to herself she took

Love felt the wound and Troy’s foundations shook

Aw’d by thy presence slumber’d at his post

With vengeful pleasure pleas’d the Goddess heard

Of future woes and then her choice preferred

The shiny mischief to herself she took

Love felt the wound and Troy’s foundations shook

Turner must have intended the ‘Ode’ as an epigraph for his picture The Goddess of Discord Choosing the Apple of Contention in the Garden of the Hesperides (Tate N00477)2 shown at the British Institution in 1806, although it was not published in the catalogue of the exhibition. In Turner’s own reworking of classical myth, the picture shows Discord choosing the apple that will eventually be awarded by Paris to the goddess Aphrodite and lead to the Trojan War and the fall of Troy. Thus it looks forward to the Judgement of Paris while, as Nicholson explains,3 conflating two other distinct stories: of Discord, annoyed at her exclusion from the festivities at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, throwing an apple inscribed ‘to the fairest’ into their midst; and of Hercules seeking the golden apples in the Garden of the Hesperides as one of his labours. Turner’s Hesperidean garden is also a combination, of pictures by Nicolas Poussin that he had seen in Paris in 18024 and his recollections of the Alps from the same year. As a realm of Arcadian innocence threatened by human folly it is partly classical Greek but also Judaeo-Christian, evoking Eden and the Biblical Fall. John Gage5 notes Turner’s association of the Apples of the Hesperides and those of the Tree of Knowledge and the similarity of the last two lines of Turner’s ‘Ode’ to John Milton’s account of Eve plucking the Apple in Paradise Lost, Book 9:

her rash hand in evil hour

Forth reaching to the fruit, she pluck’d, she eat:

Earth felt the wound, and Nature from her seat

Sighing through all her works gave signs of woe

Forth reaching to the fruit, she pluck’d, she eat:

Earth felt the wound, and Nature from her seat

Sighing through all her works gave signs of woe

Gage further suggests that Turner changed the bridal feast from that of Peleus and Thetis, as in the classical sources, to that of Psyche as a symbol of mercurial water. The picture can be seen as an alchemical allegory, with the nymphs of the Hesperides representing air and the apple the fruits of the earth. The dragon who guards it and, in the picture, appears to grow out of the mountain on which he crouches, is Ladon, son of Typhon and Echidna, creatures of fire and tempest, earth and water. He is also brother to the dragon slain by Jason in his quest for the Golden Fleece.

Gage links Turner’s pictures of dragons and serpents, which include the earlier Jason (Tate N00471)6 exhibited in 1802 and the later Apollo and Python (Tate N00488)7 exhibited in 1811, and his interest in alchemical associations to his friendship with the painter Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg, an early influence and now his neighbour in Hammersmith. Loutherbourg painted dragons including Cadmus Destroying the Dragon (sold at his posthumous sale in 1812) and his own version of Jason Enchanting the Dragon (in the Bryan collection to 1798). Moreover, he owned an extensive library of books on alchemy and the occult as well as science and chemistry, which Turner can be assumed to have consulted. Mrs Loutherbourg is said to have become so vexed by Turner’s constant visits that, fearing for her husband’s professional secrets, she drove him out of the house. Thus this verse, which at first seems so far removed from Turner’s experience at Hammersmith where he used the sketchbook, is in fact one of its closest points of contact with it.

In a satirical drawing The Artist’s Studio (Tate D08257; Turner Bequest CXXI B), datable about 1808, Turner shows a painter busy with ‘Pictures either Judgment of Paris, Forbidden Fruit’ – the themes linked in his ‘Ode’ and in The Goddess of Discord. His studio is crowded with ‘Phials | Crucibles retorts’ suggesting a fascination with mysterious nostrums. Gage sees this too as a skit on Loutherbourg, citing ‘iconographic details and the physiognomy of the protagonist’.8 The connection is disputed by Wilton9 and Anne Lyles10 on the grounds of Turner’s admiration for the older artist, but this need not have been uncritical or incompatible with humour. On the verso of The Artist’s Studio Turner wrote some verses contrasting elevated artistic taste with a more down-to-earth liking for buttered rolls, and in a companion drawing The Garreteer’s Petition (Tate D08256; Turner Bequest CXXI A) and a version in oil (Tate N00482)11 exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1809, he depicted a would-be epic poet struggling with his failing inspiration. Both subjects link aspiration in painting and poetry with those other sides of the creative coin, incompetence and bathos; they tread the fine line between the sublime and the ridiculous. Perhaps Turner’s failures to access all Loutherbourg’s secrets and (as he must have realised) to match up to his own ambitions as a poet had merged in his mind and found release in satire.

Turner’s unpublished ‘Ode’ might also have a satirical undertone. The 1806 exhibition in which The Goddess of Discord appeared was the first held by the British Institution, which had been founded the previous year by patrons and collectors to ‘encourage and reward the talents of the Artists of the United Kingdom’. In fact, artists were wary of it, resenting the fact that it was run by rich individuals who might impose their own taste. Turner’s picture, with its echoes of Poussin, was certainly calculated to appeal to the Institution, which was soon holding loan exhibitions of Old Masters and offering prizes for modern ‘companions’ to their pictures. But his verses, especially when developed to describe ‘future woes’, suggest that he foresaw trouble.12 One of the Institution’s directors, Sir George Beaumont, was a constant critic of Turner whose opinions threatened to do him serious damage, and the fire-breathing dragon that Turner painted atop a rock in the picture and described in his verses – the dragon who is also a host – might be a disguised portrait of Beaumont.13 That Turner either did not submit his ‘Ode’ along with the picture, or the Institution did not publish it, tends to support this possibility. And as it turned out, Beaumont proved true to form when he saw the picture, describing it as ‘like the works of an old man who had ideas but had lost his powers of execution’.14

Finally, it should be added that Beaumont has also been associated with the painter in Turner’s Artist’s Studio, his habit of painting his own pictures alongside examples by Old Masters and insistence on suitable deference towards them from young artists being also cited in its mention of ‘Stolen hints from celebrated Pictures’.15

David Blayney Brown

December 2009

Gage 1969, pp.136–7; John Gage, J.M.W. Turner:‘A Wonderful Range of Mind’, New Haven and London 1987, p.127.

Anne Lyles, ‘Loutherbourg, Philippe Jacques de (1740–1812)’, in Evelyn Joll, Martin Butlin and Luke Herrmann eds., The Oxford Companion to J.M.W. Turner, Oxford 2001, p.180.

Felicity Owen and David Blayney Brown, Collector of Genius: A Life of Sir George Beaumont, New Haven and London 1988, p.154.

As first suggested by Owen and Blayney Brown 1988, p.166 and most recently by Ian Warrell, “‘Stolen hints from celebrated Pictures”: Turner as Copyist, Collector and Consumer of Old Master Paintings’, in David Solkin ed., Turner and the Masters, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2009, p.47.

How to cite

David Blayney Brown, ‘Verses (Inscription by Turner) c.1806 by Joseph Mallord William Turner’, catalogue entry, December 2009, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www