Walter Sickert: The Camden Town Murder and Tabloid Crime

Lisa Tickner

The murder of a part-time prostitute in a bedroom in Camden Town caused a sensation in September 1907. Walter Sickert made a number of paintings and drawings that alluded to the killing. In this essay, first published in 2000, Lisa Tickner considers these works in the context of the murder and Sickert’s practice.

It is said that we are a great literary nation but we really don’t care about literature, we like films and we like a good murder. If there is not a murder about every day they put one in. They have put in every murder which has occurred during the past ten years again, even the Camden Town murder. Not that I am against that because I once painted a whole series about the Camden Town murder, and after all murder is as good a subject as any other.

Walter Sickert, lecture at Thanet School of Art, 19341

Walter Sickert, lecture at Thanet School of Art, 19341

‘The Camden Town Murder’ is both the name of an event, christened in the newspapers, and the title of a painting – indeed the umbrella title for a series of images.2 What they have in common is a sifting of the formal and psychological possibilities available in the juxtaposition of a clothed man, with a naked woman on an iron bedstead, in a ‘third floor back’. (Sickert sought these rooms out: where a friend saw only ‘a forlorn hole, cold, cheerless’, he saw ‘the contre-jour lighting that he loved, stealing in through a small single window, clothing the poor place with light and shadow ... [and] four walls [that] spoke only of the silent shades of the past, watching us in the quiet dusk’.3) The exact boundaries of Sickert’s series are rather fuzzy. First, because he used alternative titles for the same images and sometimes overlapping titles for different ones; and second, because there are at its margins peripheral works – like Dawn: Camden Town – which share the locality, the bedroom interiors and the sinister charge, but without any reference to murder in their titles.

In what follows I look first at the undisputed Camden Town Murder paintings; then at their referent (the murder as an event); then at their rather hybrid genre (at the question of how these are or are not ‘nudes’ in the context of prostitution and murder); and finally at death, as modern subject matter.

Camden Town Murder pictures

There are three main oils:

Summer Afternoon, or What shall we do for the Rent? (Kirkcaldy Museum and Art Gallery, Fife, c.1907–9; fig.1). There is a closely related but cropped version in a private collection and these seem to have been the paintings exhibited at the first exhibition of the Camden Town Group at the Carfax Gallery, London, in June 1911 as The Camden Town Murder Series No.1 and No.2;

The Camden Town Murder, or What shall we do about the Rent? (Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, c.1908; fig.2); and

L’Affaire de Camden Town (exhibited in Paris and bought by Paul Signac in 1909; now in a private collection; fig.3).

The Camden Town Murder, or What shall we do about the Rent? (Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, c.1908; fig.2); and

L’Affaire de Camden Town (exhibited in Paris and bought by Paul Signac in 1909; now in a private collection; fig.3).

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Summer Afternoon or What Shall We Do for the Rent? c.1907–9

Oil paint on canvas

515 x 410 mm

Fife Council Libraries & Museums: Kirkcaldy Museum & Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Antonia Reeve

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Summer Afternoon or What Shall We Do for the Rent? c.1907–9

Fife Council Libraries & Museums: Kirkcaldy Museum & Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Antonia Reeve

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Camden Town Murder or What Shall We Do about the Rent? c.1908

Oil paint on canvas

256 x 356 mm

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund B1979.37.1

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

The Camden Town Murder or What Shall We Do about the Rent? c.1908

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund B1979.37.1

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

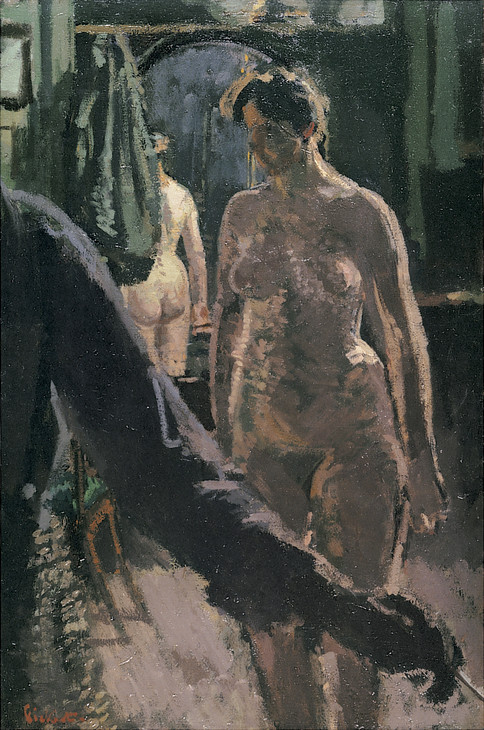

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

L'Affaire de Camden Town 1909

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 406 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Photographic Survey, Courtauld Institute of Art

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

L'Affaire de Camden Town 1909

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Photographic Survey, Courtauld Institute of Art

The second position insists on the essentially pictorial value of modern painting. Whether or not pictures are acknowledged as rooted in the social world, that is not how they are best appreciated or understood. Roger Fry, reviewing Sickert in the Nation in 1911, ignored his titles and downplayed his subject matter. According to Fry, he is ‘almost indifferent to what he paints, his care being altogether for the manner of it’; and he has ‘steadily refused to acknowledge the effect upon the mind of the associated ideas of objects; he has considered solely their pictorial value as opposed to their ordinary emotional quality’.5

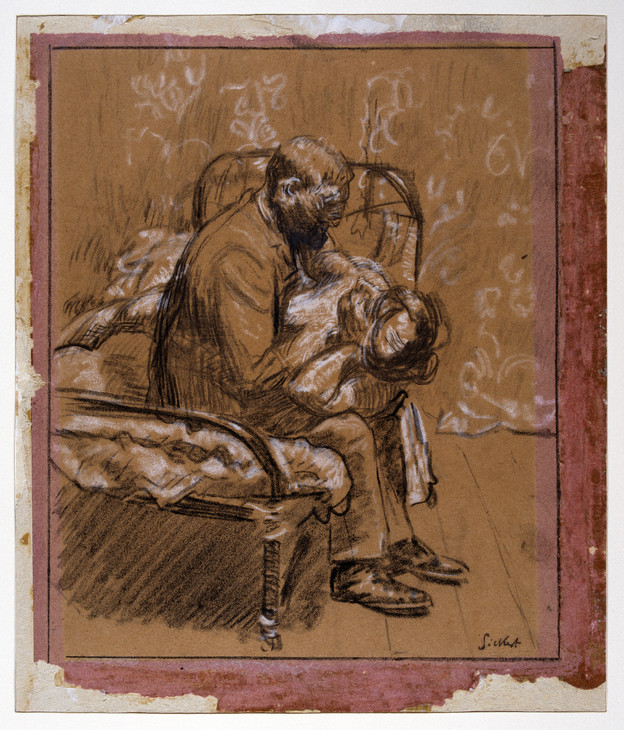

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Camden Town Nude: Conversation c.1908–9

Black chalk heightened with white, pen and ink on buff paper

337 x 235 mm

Royal College of Art, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Royal College of Art

Fig.4

Walter Richard Sickert

Camden Town Nude: Conversation c.1908–9

Royal College of Art, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Royal College of Art

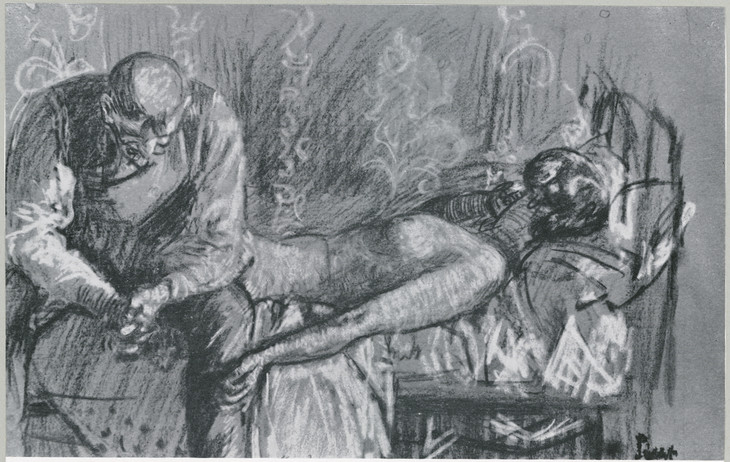

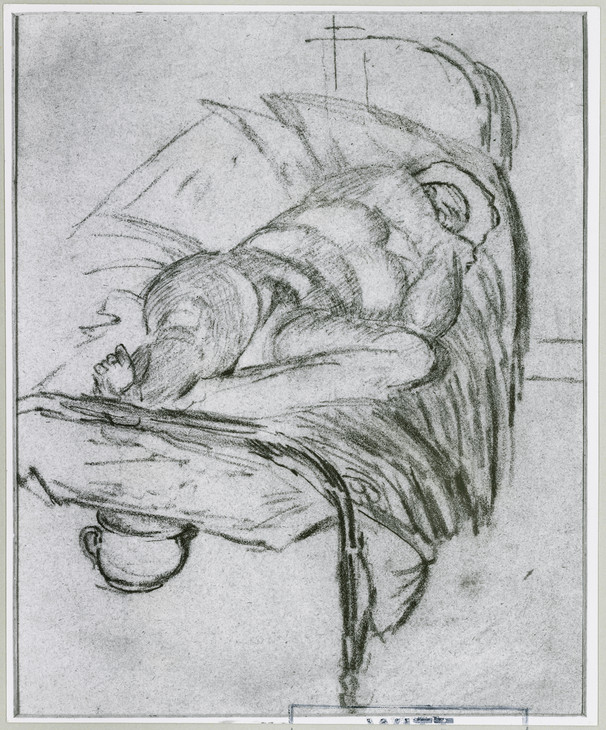

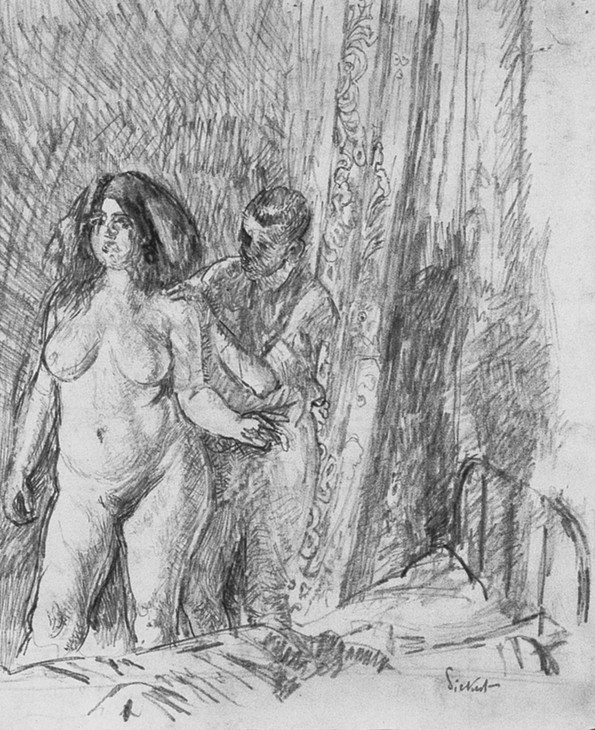

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Study for 'L'Affaire de Camden Town' c.1909

Chalk on paper

355 x 229 mm

Private collection, Paris

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

By courtesy of the Witt Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London

Fig.5

Walter Richard Sickert

Study for 'L'Affaire de Camden Town' c.1909

Private collection, Paris

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

By courtesy of the Witt Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London

Something of this is true, of course. Paintings grow out of other paintings, out of the promise or failure of certain moves, as well as out of the social compost. The Camden Town Murder pictures have various precedents in Sickert’s paintings of 1903–7 and, as Wendy Baron has pointed out, L’Affaire de Camden Town develops into a scene of brutal murder from ‘the precise compositional springboard’ of the two women in Camden Town Nude: Conversation c.1908–9 (fig.4).6

Sickert was cavalier about titles. In 1910 he wrote:

Pictures, like streets and persons, have to have names to distinguish them. But their names are not definitions of them, or, indeed, anything but the loosest kind of labels that make it possible for us to handle them, that prevent us from mislaying them, or sending them to the wrong address.7

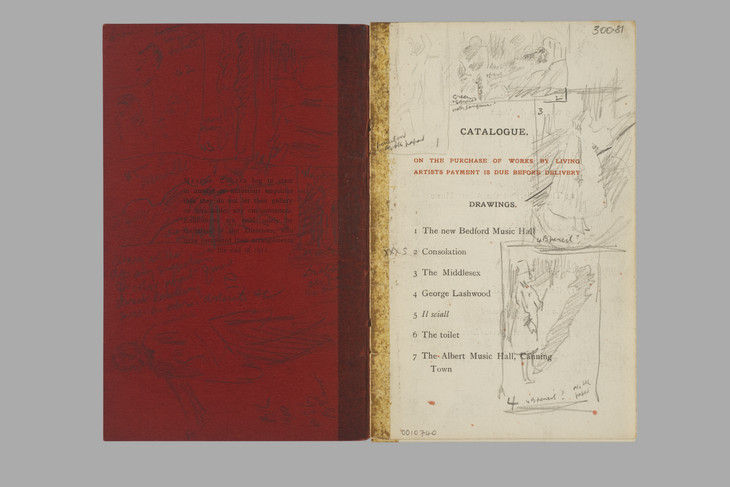

Anna Robins has published pages from the catalogues for the Carfax Gallery exhibitions of 1911 and 1912 (fig.6).8 The copies in the Tate Gallery Library are annotated with comments and sketches, and from these it emerges that the drawing of a clothed man in conversation with a naked woman on a bed, etched as The Camden Town Murder, was exhibited as A Consultation; La Belle Gâtée or The Camden Town Murder as Persuasion (fig.7); and The Camden Town Murder or What shall we do for the Rent? as Consolation (fig.8). In each case the resonance of the image shifts with the title. We might consider that the titles of the drawings fix the meanings of the paintings – that we should read the ambiguities of The Camden Town Murder, for example, by reference to an idea of ‘consolation’ rather than violence. It anchors the image in a different way. But there is no evidence that the titles of the drawings are earlier or more apposite, since both drawings and paintings were produced two to three years earlier. They were more likely titled for the purpose of exhibiting them separately in January 1911, and in advance of the first public exhibition of the Murder paintings in Britain that June.9

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Persuasion (previously known as The Camden Town Murder, or La Belle Gâtée) c.1908

Chalk on paper

267 x 222 mm

Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery

Fig.7

Walter Richard Sickert

Persuasion (previously known as The Camden Town Murder, or La Belle Gâtée) c.1908

Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Study for 'The Camden Town Murder' c.1908

Chalk on paper

235 x 375 mm

Private collection, USA

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

By courtesy of the Witt Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London

Fig.8

Walter Richard Sickert

Study for 'The Camden Town Murder' c.1908

Private collection, USA

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

By courtesy of the Witt Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Mornington Crescent Nude, Contre-Jour 1907

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 611 mm

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 0.1977. A.R. Ragless Bequest Fund 1963

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert/DACS 2011

Photo © Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Fig.9

Walter Richard Sickert

Mornington Crescent Nude, Contre-Jour 1907

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 0.1977. A.R. Ragless Bequest Fund 1963

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert/DACS 2011

Photo © Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

This sense of a narrative runs against the grain of what has come to be construed as ‘modern’ in modern art. But Sickert insisted that ‘All the great draughtsmen tell a story’.16 He maintained that no country could have a great school of painting when the unfortunate artist was confined ‘to the choice between the noble site as displayed in the picture-postcard, or the quite nice young person, in what Henry James has called a wilderness of chintz’.17 He was a self-proclaimed realist and literary painter with an interest in narrative and an obsession with facture. (He called it ‘the cooking side of painting’.18) He did not believe in severing subject and treatment:

Is it not possible that this antithesis is meaningless, and that the two things are one, and that an idea does not exist apart from its exact expression? ... The real subject of a picture or a drawing ... and all the world of pathos, of poetry, of sentiment that it succeeds in conveying, is conveyed by means of the plastic facts expressed ... If the subject of a picture could be stated in words there had been no need to paint it.19

It is in this sense – rather than in any quibbling as to the recorded details of Emily Dimmock’s murder in 1907 – that Sickert’s paintings are not illustrations. They cannot be decanted into words. And they do not use the available ‘language’ of illustration for sensational events, evident in the depictions of the Camden Town Murder in such publications as the Illustrated Police Budget and News.20 But their subject matters. This seeps through even in Fry’s review, when, having stressed the detachment of Sickert’s vision and the essentially pictorial nature of his ambition – things are ‘not symbols’ for Sickert and ‘contain no key to unlock the secrets of the heart and spirit’ – Fry grudgingly acknowledged his ‘persistent devotion to the banal and trivial situations of ordinary life, at times even an attraction for what is squalid’.21

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

La Hollandaise c.1906

Oil paint on canvas

support: 511 x 406 mm; frame: 722 x 630 x 104 mm

Tate T03548

Purchased 1983

© Tate

Fig.10

Walter Richard Sickert

La Hollandaise c.1906

Tate T03548

© Tate

The referent

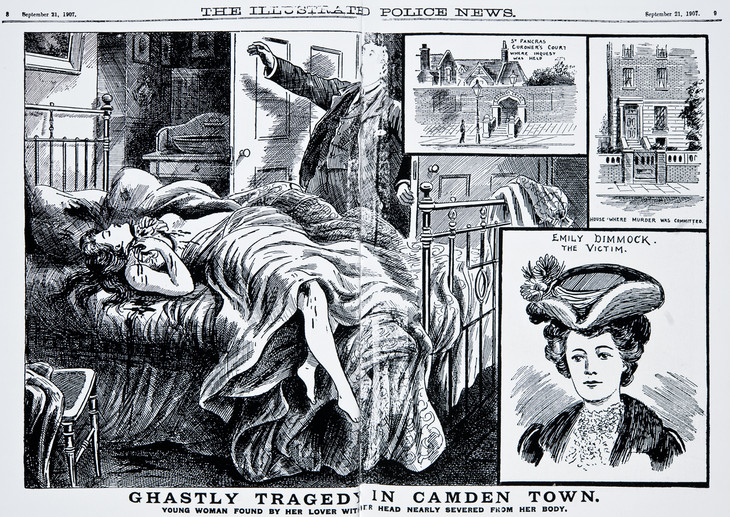

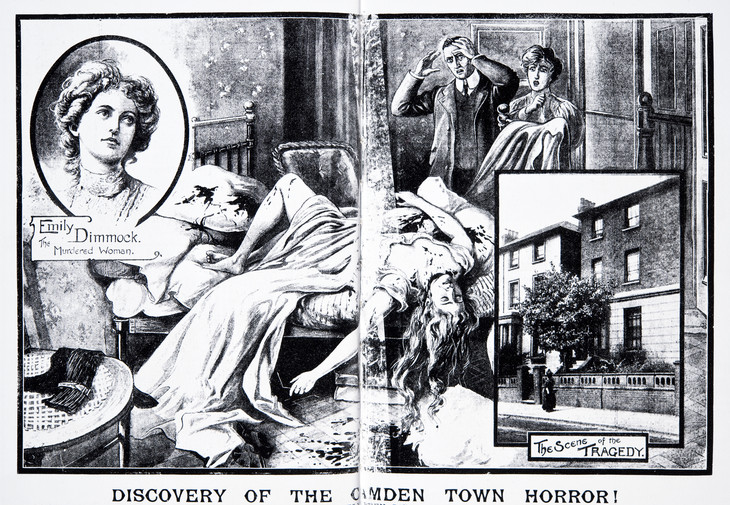

In the early hours of 12 September 1907 Emily Dimmock, an attractive, twenty-two-year-old blonde prostitute, was murdered in her bed in Camden Town.33 Her naked body was discovered later that morning by her common-law husband, Bertram Shaw, who returned from his night-shift in the restaurant car of the Sheffield Express at half past eleven. Dimmock lay slightly on her left side, with her left arm pulled awkwardly behind her, her right hand on the pillow, and the sheet drawn up over her naked body. The front of her hair was in curling pins. Her throat was cut from ear to ear, severing her head almost completely from her body.34 Blood had soaked into the sheets and on to the floor below. The remains of a supper eaten by two people lay on the table. There was a basin on the washstand full of bloody water with one of the victim’s flannel petticoats, which the murderer had used to clean his hands.

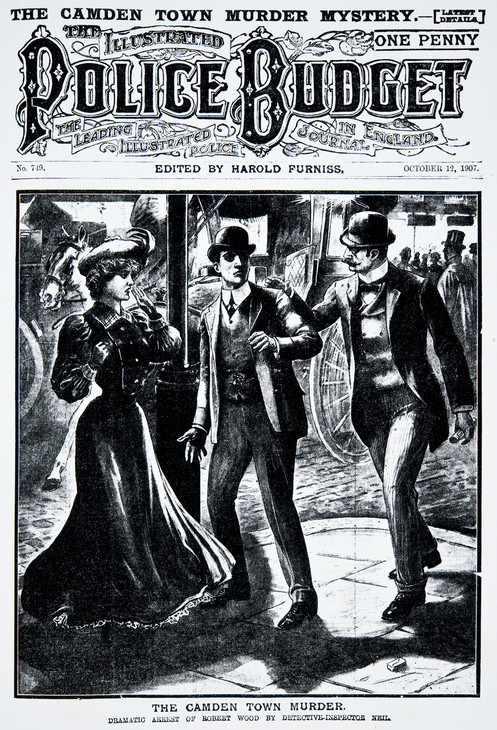

The St Pancras Chronicle reported the story on 13 September – ‘Camden Town Tragedy. Woman Hacked to Death. Mysterious Crime’ – noting in its next issue that the tragedy was already ‘the main topic of newspaper gossip and chatter’.35 Crowds gathered at the coroner’s and magistrates’ courts and thousands lined the route of Emily Dimmock’s funeral cortège to St Pancras Cemetery. The drama of the trial was heightened by the shadow of the gallows, by the fact that the defendant for the first time in a murder trial gave evidence on his own behalf, and by the brilliant performance of Sir Edward Marshall Hall in his defence. The Penny Illustrated Paper called it ‘the most remarkable criminal trial held within the past fifty years’.36 The public gallery was packed and distinguished visitors including Hall Caine, Arthur Pinero, Henry Irving and George Sims were admitted by ticket. When the verdict was due on 18 December between seven and ten thousand people thronged the Old Bailey exits and stretched into Ludgate Circus. Traffic was at a standstill and when the news of Robert Wood’s acquittal was finally flashed down the wires, theatrical performances were interrupted to announce it.37

This level of public attention was sustained by several factors. First there was the morbid fascination of sex and death. But more specifically, there was the inevitable incitement and framing of this fascination provided by both nineteenth-century fictional genres like the detective story, and by the prominence of sex and crime in the popular press (in the News of the World, for instance, and in the Police Illustrated News, the Penny Illustrated Paper and the Illustrated Police Budget). David Napley remarked perhaps too casually that: ‘Each succeeding day of the murder trial unfolded to the public a story as enthralling as any novel, as dramatic as any play and as intriguing and mystifying as any detective story’.38 It did so not just because the trial was ‘like’ these literary forms or as dramatic in its effects, but because crime and punishment (and prostitution) were the great themes of nineteenth-century literary realism and the detective story one of the most widespread genres in popular fiction. Sex, sport and crime were the staples of the popular press, as they still are and as they had been for the hawkers of nineteenth-century broadsheets.39 Newspapers offered an unfolding narrative of the search for truth – the truth of Emily Dimmock’s days and end, the reasons for her fall into ‘an irregular life’ as one of ‘the lowest class of unfortunates’,40 the identity of her murderer and his motives – so that each day, each week, brought new instalments, new evidence, new hypotheses, a shifting of the ground that promised to settle into some new and finally satisfying pattern of comprehensible cause and effect.

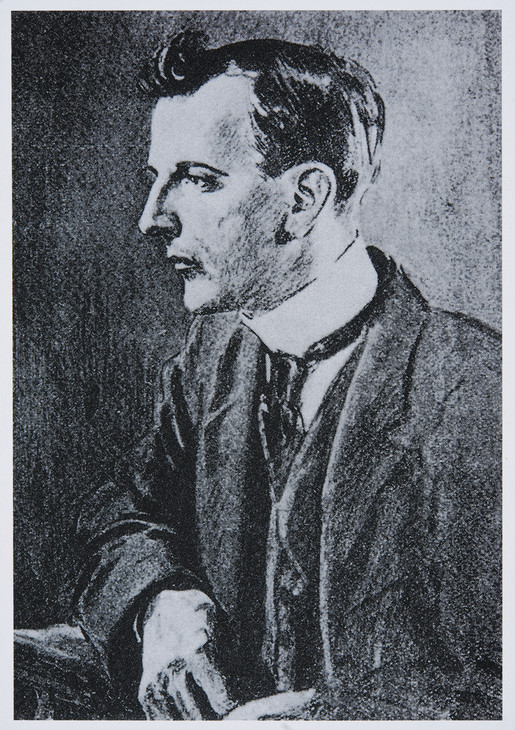

Joseph Simpson 1879–1939

Robert Wood

Reproduced in Basil Hogarth (ed.), Trial of Robert Wood (The Camden Town Case), William Hodge, London and Edinburgh 1936

Fig.11

Joseph Simpson

Robert Wood

Reproduced in Basil Hogarth (ed.), Trial of Robert Wood (The Camden Town Case), William Hodge, London and Edinburgh 1936

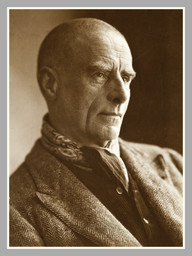

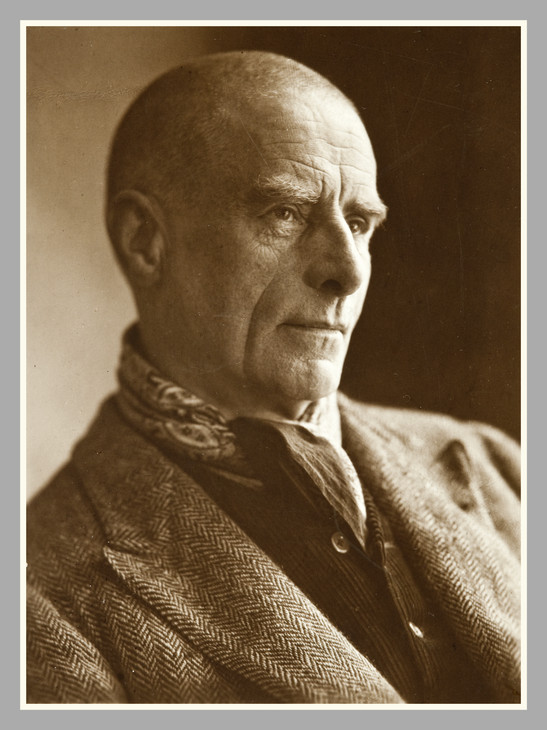

Walter Richard Sickert with his Head Shaved c.1920

Photograph, black and white, on paper (photographer unknown)

149 x 110 mm

Inscribed in an unknown hand 'Photo of Sickert, he shaved his head' on back

Tate Archive TGA 8120/2/3

Fig.12

Walter Richard Sickert with his Head Shaved c.1920

Tate Archive TGA 8120/2/3

Nevertheless the brutal and apparently inexplicable murder of a young prostitute now carried the shadow of sex-crime with it. Marshall Hall’s opening speech for the defence asked if it was credible that a man with Wood’s excellent character would go to Dimmock’s house, murder her, wait until five o’clock in the morning and then return to work calm and collected:

Is it not much more probable that the crime is the work of a sexual maniac – a murder similar to the murders which paralysed all London many years ago? Is it not possible that this woman, who had descended to the lowest depths of prostitution, should have become acquainted with some man who proved to be a maniac seeking for his prey?51

Sickert was already fascinated by Jack the Ripper. Osbert Sitwell recalled that his talk contained ‘certain invariable strands, certain immutable monuments’ – chief among them the Tichborne Claimant and Jack Ripper.52 Marjorie Lilly knew him when he worked on the Murder paintings and also noted this obsession with ‘crime personified by Jack the Ripper’. She described his studio in Fitzroy Street, known as the ‘Frith’ (because William Powell Frith had painted there), as ‘a huge, bare, carpetless barn engulfed in shadows, thick with dust and the odour of paint and cigars’, with by the door an iron bedstead, a hanging bookcase and a honeycomb quilt. With these he constructed his mis-en-scène. (Sickert had started out as an actor and was not above thinking himself into the part.) There was ‘a red Bill Sykes handkerchief dangling from the bedpost’ which she called ‘a lifeline to guide the train of his thought’.

Sickert was working now on one of his Camden Town murders and while he was reliving the scene he would assume the part of a ruffian, knotting the handkerchief loosely round his neck, pulling a cap over his eyes and lighting his lantern. Immobile, sunk deep in his chair, lost in the long shadows of that vast room, he would meditate for hours on his problem.53

The handkerchief ‘played a necessary part in the performance of the drawings, spurring him on at crucial moments, becoming so interwoven with the actual working out of his idea that he kept it constantly before his eyes’.54 (Even the landlady respected the handkerchief and left it alone when she came in to clean.) In effect, Lilly conflated the Camden Town Murder paintings with Sickert’s interest in Jack the Ripper, suggesting that if the event of 1907 was the immediate spur to these unprecedented paintings, what lay behind and had now merged with them was the ‘autumn of terror’ of 1888. Or perhaps they were not unprecedented: Sickert told Keith Baynes that he had painted a picture of Jack the Ripper in 1906, but nothing survives.55

Despite various precedents the Ripper had become – with the expansion of the daily press and the popularising of an emergent sexology – the founding father of modern sex-crime.56 His crimes were random, serial and apparently motiveless. Signing himself ‘Jack the Ripper’, he described himself to the press as ‘down on whores and I shan’t quit ripping them up until I get buckled’.57 Richard von Krafft-Ebing, author of Psychopathia Sexualis, with Especial Reference to the Antipathetic Sexual Instinct: A Medico-Forensic Study in 1885, added him to a new edition as ‘case 17’ in the section on sadistic crimes and lust murders.58 He was ‘a new gynocidal archetype’.59 As the Southern Guardian put it: ‘We are face to face with some mysterious and awful product of modern civilisation’.60 The question for Sickert is then that of sexual- or lust-murder as a modern subject in modern art.

Acknowledging that Sickert’s paintings are not illustrations of the event, one might nevertheless compare them with descriptions and images that are or claim to be. This helps throw into relief the kinds of pictorial choices that Sickert made, and reconstitutes something of the ‘noise’ of urban reportage, audible in popular memory, against which they figured, as in the double-page spreads from the Illustrated Police News and the Illustrated Police Budget (figs.13 and 14). 61

Ghastly Tragedy in Camden Town 21 September 1907 Illustrated Police News

British Newspaper Library, Colindale, London

Photo © British Newspaper Library, Colindale, London

Fig.13

Ghastly Tragedy in Camden Town 21 September 1907 Illustrated Police News

British Newspaper Library, Colindale, London

Photo © British Newspaper Library, Colindale, London

Discovery of the Camden Town Horror! 21 September 1907 Illustrated Police Budget

British Newspaper Library, Colindale, London

Photo © British Newspaper Library, Colindale, London

Fig.14

Discovery of the Camden Town Horror! 21 September 1907 Illustrated Police Budget

British Newspaper Library, Colindale, London

Photo © British Newspaper Library, Colindale, London

Those anonymous artists were unlikely to have visited the scene of the crime, were not yet privy to details that emerged at the inquest, and were not hired to produce a pictorial report. They filled a general structure – the violent and sexual death of a beautiful woman – with local content.62 This is gothick, melodramatic representation in broadsheet style. It is drawn for an audience, as it would be acted on stage. (It is the second act: what life led up to this has to be determined retrospectively, and the dénouement – the solution to the mystery and the bringing to justice of the murderer – is yet to come.)

Both illustrations use the standard formula of a double-page spread combining the dramatic moment – the discovery of the body – with appended vignettes. Both stage the same scene from the same viewpoint. A bloody and partially naked body is sprawled on a double bed (brass and iron: more elaborate than Sickert’s). In fact if the body is isolated from its immediate context – from the horrified expressions of Shaw and his landlady and the caption beneath – it is the blood that transforms a pompier pose of sexual abandon into the image of a brutal assault.63

Images like these are a curious blend of the circumstantial detail of reportage and the Victorian narrative tradition, with the essentially dramatic codes of Baroque and neoclassical history painting. They throw into relief the nature of Sickert’s refusals: instead of the set tableaux, the keyhole view; instead of the dramatic moments of death or discovery, a silent, sinister but ambiguous communion; instead of the anecdotal details, an almost claustrophobic insistence on the figures and the bed; instead of the sprawling, prurient, blood-spattered nudes, a sense of anonymous, shockingly explicit, middle-aged flesh.

And yet simultaneously Sickert was fighting a rearguard action against the rejection of narrative in modern painting. Narrative had been central both to the ‘elevated’ traditions of academic history painting and the popular forms of domestic genre, but towards the turn of the nineteenth century ‘advanced’ artists began to stress pictorial elements at the expense of an explicit engagement with narrative and subject matter. Sickert believed that the narrative tradition was far from exhausted. He denounced ‘the Whistlerian anti-literary theory of drawing’, insisting, ‘All the greater draughtsmen tell a story’.64 In 1912, against a gathering tide of critical opinion, he maintained: ‘the whole field of natural “genre” pictures, desolated by the error of scale introduced by competitive exhibitions, is waiting to be re-tilled on the lines, say, of Hogarth, of Wilkie, of Longhi’.65

The period of Whistler’s eminence was also the great period of illustrated journalism. Sickert’s father and brother were illustrators and he had been one himself.66 Asking, rhetorically, who was the greatest English artist of the nineteenth century, Sickert – who might have named Constable, Turner, Whistler or Rossetti – proposed that ‘it would be difficult even to find a candidate to set against Charles Keene, a draughtsman on a, then, threepenny paper’.67 The Camden Town paintings are indebted to this graphic tradition, and to Victorian ‘realists’ like Herkomer and Fildes. But they also owe something to the Edwardian ‘problem picture’, another popular narrative genre, and its sudden demise around 1908.

The problem picture, as Pamela Fletcher has pointed out, was ‘one of the most anticipated and publicised features of the late Victorian and Edwardian Royal Academy’.68 These were paintings that offered morally and narratively ambiguous scenes of contemporary life, open to a range of interpretations and solutions. Viewers responded with enthusiasm in newspaper competitions and in letters to the artists and the press. In the process of completing and explaining the paintings they invented their own narratives and ‘grappled with the new social terrain of the early twentieth century, in particular the changing roles available for modern women’. Fletcher argues that ‘the Edwardian “problem picture” was one attempt to utilize the indeterminacy inherent in narrative to create a socially engaged form of public art’, but that the attempt failed, as the opposition between ‘the narrative’ and ‘the modern’, set in place by artists and critics, was increasingly absorbed as common sense. The subject matter was contemporary; but its exploration through narrative came to seem increasingly old-fashioned – illustrative and moralising – rather than modern.

John Collier 1850–1934

Sentence of Death 1908

Oil paint on canvas

1295 x 1626 mm

Wolverhampton City Art Gallery

Photo © Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Fig.15

John Collier

Sentence of Death 1908

Wolverhampton City Art Gallery

Photo © Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Sickert did not so much paint a narrative as borrow one off the peg in the newspapers. He directed his viewers to a particular event but did not quite picture it. The event itself remained mysterious. Why did Emily Dimmock resume her ‘irregular life’? Why did a respectable man consort with prostitutes? Who was the murderer? What was the motive?70 But the questions, though hotly debated, did not add up to the public discussion of a general issue – prostitution, sexual violence, masculinity – in a way that could ground the terms for a ‘problem’ picture. This in a way was Sickert’s point. He was not concerned with middle class wives or prodigal daughters in the Collier mould. Dimmock was not a ‘fallen woman’. She had no social and moral status from which to fall. This was her job, not her disgrace. And because of her class, though there is ambiguity, there is no moral conundrum here of the kind required to provide the kernel for a problem picture (and its very particular relations with its audience).

Sickert produced a decipherable image but not a readable event. This has to do with his handling of narrative and his handling of paint. No artist can paint, except sequentially, the passage of time – the movement from stasis, to action, to (a modified) stasis that makes up the basic structure of narrative. The usual solution is to focus on the action and weave in hints of a ‘before’ and an ‘after’. Sickert’s milieu is electric with violence but nothing is happening. He paints the stasis before or after; it is not clear which. Form is conjured and cancelled at once in the flickering web of his painterly hatchings and crusty facture; features, gestures, setting, accessories are buried or blurred. The scribbled and crumbly impasto insists in the modernist fashion on its presence as paint. Dragged, stiff-bristled strokes produce a flecked, animated, tactile surface. And yet the painting holds on to narrative. The medium is not at odds with the subject but invades and extends it: against Sargent’s ‘wriggle and chiffon’ the ‘gross material facts’ of pigment come to stand in for the ‘gross materiality of working class urban space’.71 There is a novel and covert beauty here; what Sickert himself called ‘attar of roses wrung from flint’.72 But he built through his title, his subject, his model and his handling the ultimate riposte to Whistlerian elegance: to Symphony in White, to taste as ‘the death of a painter’, to the received category of the ‘aesthetic’ (‘for me it’s the rudest word I know’).73

Pamela Fletcher argues that viewers learned to dismiss the ‘problem picture’ as it was overtaken by advertising, and as painterly ambitions shifted to ‘significant form’. They learned to distinguish between commerce and culture, the ‘narrative’ and the ‘modern’. In the process the audience divided, between those who were knowledgeable about art and those who were not (‘the so-called “shilling public” of “suburban” women’). Knowledgeable viewers split their responses to different kinds of visual imagery and ‘learned to aspire to a private and imaginative aesthetic experience rather than a public and social conversation in front of a work of art’. Sickert was loath to make this choice. When he urged Virginia Woolf that he had ‘always been a literary painter, like all decent painters, do be the first to say so’, this was not a cynical feint, but an expression of his social ambitions for art.74 Virginia Woolf, finding herself out of kilter with Bloomsbury aesthetics, turned to her nephew Quentin Bell: ‘Do you think one could treat his paintings like novels? ... What do you think of Sickert’s painting? I gather Roger is rather down on it; so is Clive. It seems to me all that painting ought to be. Am I wrong? if so, why?’75

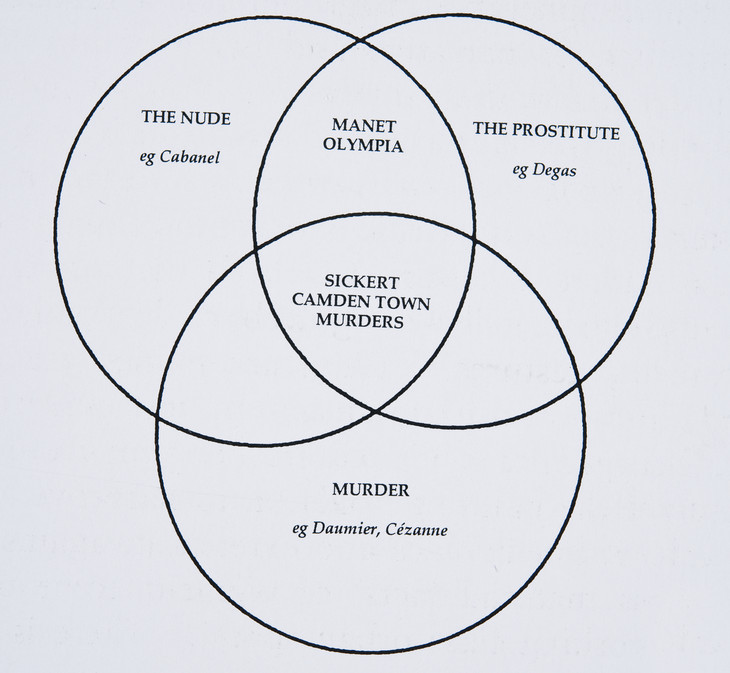

Genre: The nude, the prostitute, the murder victim

The Camden Town Murder paintings could be imagined as occupying the overlapping area of three circles in a Venn diagram (fig.16). One is labelled ‘the nude’ (e.g. Cabanel’s Venus); one the ‘prostitute’ (e.g. Degas’s Women on the Terrace of a Café) and one ‘murder’ (e.g. Daumier’s Rue Transnonain, le 15 Avril, 1834 or Cézanne’s The Murder). The conflation of ‘nude’ and ‘prostitute’ would be most securely represented by Manet’s Olympia (fig.17). As T.J. Clark has put it, Olympia ‘altered and played with identities the culture wished to keep still, pre-eminently those of the nude and the prostitute’.76 R.H. Wilenski, a critic defending Sickert from the charge of gratuitously ‘sordid’ subject matter, insisted that The Camden Town Murder was ‘just a technical experiment by Sickert who thought it would be fun to take Manet’s Olympia and paint it the other way round’.77 I shall take this comment seriously as a way into the discussion of the Camden Town Murder paintings as ‘nudes’.

Edouard Manet 1832–1883

Olympia 1863

Oil paint on canvas

1300 x 1900 mm

Musee d’Orsay, Paris

Photo © Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.17

Edouard Manet

Olympia 1863

Musee d’Orsay, Paris

Photo © Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

Second, prostitution. The prostitute was a central figure in nineteenth-century art and literature: a standard solution to the problem of modernising the realist nude, and a standard trope in which to embody the alienation, specularisation and commodification of the modern city.86 The rigidity of the ideological distinction between ‘respectable’ and ‘fallen’ women, and the moral scapegoating of the prostitute as a sexual deviant, provided the prostitute with a particular narrative trajectory in art and literature. This was true in Victorian narrative painting and among artists of the Second Empire in France, and it was as much the case with Flaubert, Baudelaire, Courbet and Manet as it was with Salon artists and in popular literature. In France, Baudelaire wrote of ‘all the various types of fallen womanhood’ in ‘that vast picture-gallery which is life in London or Paris’, on a descending scale from the gilded courtesans to ‘the poor slaves of those filthy stews’.87 In Britain, paintings like G.F. Watts’s Found Drowned and Augustus Egg’s Past and Present invoked a passage from rural or wifely innocence to seduction, betrayal, prostitution, poverty and suicide by drowning. This was the standard narrative of political, legislative, medical and reforming discourses on immorality. The only difference in the case of art, as Lynda Nead has pointed out, was that aesthetic requirements might modify the expectation that the ravages of the deviant life be clearly legible on the deviant body.88

All the evidence suggests that this was wrong: that is, that the standard narrative of the prostitute’s decline had little to do with the social reality of prostitution and a great deal to do with the conviction that the wages of sin must be death.89 Women’s entry into prostitution was apparently voluntary, gradual and not necessarily permanent. The social profile of the prostitute was unskilled, poor working class, with local origins but displaced family relations (like Emily Dimmock, the youngest of fifteen children, who started her working life in a straw-hat factory in Bedford). Prostitution offered a temporary solution to pressing problems – like what to do for the rent – and limited social and economic independence. Many women moved on or married out of it. Emily Dimmock, who was young, attractive, sociable and settled with Bertram Shaw, might have done so too. But she fell victim to a sex-murderer. After the impact of the Ripper crimes in 1888 this was the new narrative ending for the prostitute’s life. Jack the Ripper switched the rails, as it were, from an imaginary trajectory that ended in shame, disease, poverty and a watery suicide to one that ended in bloody violence, in ‘retribution’ at the hands of a pervert, ‘down on whores’ who wouldn’t ‘quit ripping them’ until he was ‘buckled’. No one had painted this yet. It was a new subject, and it was to become, alas, one of the principal sexual narratives of the twentieth century.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Study for 'L'Affaire de Camden Town' c.1909

Chalk on paper

268 x 213 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

By courtesy of the Witt Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London

Fig.18

Walter Richard Sickert

Study for 'L'Affaire de Camden Town' c.1909

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

By courtesy of the Witt Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London

It is perhaps worth noting two things at this point. First, that Sickert was very well acquainted with the French art world; he was in other paintings (like Cocotte de Soho) indebted to Manet and he certainly knew Olympia.92 Second, that Olympia, which had caused such a scandal in 1865, had become something of an old master by the time it entered the Louvre from the Luxembourg and was hung next to Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque in 1907. Proust’s Oriane de Guermantes remarks: ‘The other day ... at the Louvre, we came across Manet’s Olympia. Nobody is astonished by it any more. It looks like something by Ingres! And yet heaven knows I’ve broken many a lance for this painting which I don’t entirely like’.93 Mapping the prostitute on to the nude – facing and confusing the body in art (as symbol) with the body in life (as commodity) – produced a subversive, modern, hybrid imagery which congealed into old-masterdom in its turn.

Third, murder. In 1907 Olympia no longer represented the seamy side of the classic nude or refused so unequivocally the available and acceptable category of the courtesan.94 Emily Dimmock offered death – casual, brutal, unseemly, ungainly and anti-heroic in the realist mode – as a new gambit in the game of ‘realising’ the nude. She did not do this in a way rooted in the interplay of socio-political forces, like Daumier’s Murder in the Rue Transnonain – she might have done, but Sickert was distanced from his sister’s feminism – but just as a bit of the flotsam and jetsam of contemporary life washed up on the newspaper’s front page.95 (This is the paradox of modern newspapers, that tragedy is tragedy because it violates our sense of order, but newspapers reorder that sense to make tragedy common.96) Murder does a certain amount of work for the realist body here. It raises the stakes in invoking an underside of prostitution which was once itself the underside of the nude. It displaces the nude as an allegorical or idealising category with the particularity of flesh, pain, weight, muscle-tone and vulnerability. It enacts that vulnerability lovingly, dramatising a struggle between flesh and paint, pattern and form, resolution and dissolution, in a mode that leads on to Bacon and Freud. And it offers us the peculiarly modern spectacle of sexual murder, even though – as Max Kozloff said in another context – ‘How not to say too much seems to have become a matter of utmost laborious concern for Sickert’.

The Camden Town Murder: Dramatic Arrest of Robert Wood by Detective-Inspector Neil 12 October 1907 Illustrated Police Budget

British Newspaper Library, Colindale, London

Photo © British Newspaper Library, Colindale, London

Fig.19

The Camden Town Murder: Dramatic Arrest of Robert Wood by Detective-Inspector Neil 12 October 1907 Illustrated Police Budget

British Newspaper Library, Colindale, London

Photo © British Newspaper Library, Colindale, London

Newspapers saturated and ‘textualised’ the urban environment. They were the chief element in what has been called the ‘word city’, paralleling and mediating the social geography of the modern metropolis.106 The mass expansion of the press in the late nineteenth century was the consequence of increasing literacy combined with intensely competitive pricing and new forms of popular journalism. By 1910, London boasted twenty-eight morning and nine evening papers.107 They helped to fashion the urban experience. They advertised the latest commodities (were, indeed, among the first, mass-produced, instantly obsolescent commodities). They soothed commuting time and enlivened leisure time. They structured the day (Hegel said that they served as a modern substitute for morning prayers). They offered the ‘imagined community’ of a common readership consuming ‘one-day-best-sellers’ almost simultaneously.108 They were above all ‘inseparable from the modern city and served as the perfect metonym for the city itself’.109

The newspaper both is, and is not, a narrative form, offering of necessity a series of slices through a plotless flow. Its defining characteristics were, and remain, the apparent arbitrariness – the substitutability – of its constituent items and their abrupt transitions. A newspaper is a mosaic of disjunctive parts assembled into the approximate and provisional unity of a familiar layout and a common date (things are happening independently but they are happening at the same time).110 On the one hand the newspaper promises to clarify and order the opacity and diversity of the modern city. On the other, the sheer proliferation of its stories emphasises the heterogeneity, the ultimate unknowability, of activities that take place locally but invisibly, and among strangers. As Barthes wrote: ‘If we did not read the newspaper, our surroundings would not appear nearly as astonishing or apocalyptic’.111

Because newspapers were ineluctably contemporary they came to signify the modern, the contingent and the everyday. Because they were popular and cheap they seemed accessible and democratic. (Sickert valued genre painting because the narration ‘of things in which anyone may take an interest’ furnished a bridge across ‘the much-discussed chasm between the producer and the consumer’.112) Because they were voraciously curious they opened up the smallest byways of the city to imaginative passage. (‘Anything!’ Sickert wrote in 1910. ‘This is the subject matter of modern art. There is the quarry inexhaustible for ever.’113) But their stranded narratives were of necessity substitutable and incomplete, so that against their best intentions they frustrated the reader’s desire to know. Sickert, in the Camden Town Murder paintings, registered the look of things, how taciturn they are, rather than making objects and gestures figure the drama as in a Victorian ‘problem picture’. Despite his admiration for a journeyman-illustrator like Keene (whom he regarded as one of the great draughtsmen of the nineteenth century), he was closer to ‘an aesthetic of the newspaper’ than to illustrators like those in the Police Budget and News. Sickert adds nothing to our image of the scene or to our knowledge of the event. This is the indifference of the newspaper: the momentary frisson of one more (shocking, sordid, titillating) story, rapidly overtaken by more pressing concerns in the reader’s own life. Borrowing from the newspapers – his titles make this explicit – was a way of resisting allegory, of registering the ordinariness and the ultimate unknowability of the modern world.114 In 1912 a critic observed that Sickert ‘never goes very deep beneath the surface of things. He illustrates life but never illuminates it.’115 In fact the reverse is true. In his rejection of the dramatic moment and the telling detail (beloved of journalists), Sickert cedes us the ‘beholder’s share’: he illuminates life, but does not illustrate it.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Studio: The Painting of a Nude 1906

Oil paint on canvas

750 x 495 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Courtesy of Browse & Darby

Fig.20

Walter Richard Sickert

The Studio: The Painting of a Nude 1906

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Courtesy of Browse & Darby

the practice of art, no more than lawn-tennis or chess, is not a natural thing. It is a highly artificial game, with conditions that have been evolved by players of the past in the same manner as has the form and exact make of a cricket bat. Its limitations are peremptory and permit of no excursions.116

The theme of a naked woman with a clothed man, which dominates Sickert’s painting in the Camden Town period, first enters his work about 1906–7 with The Studio: The Painting of a Nude (fig.20) and The Poet and his Muse, also known as Collaboration.117 As the titles suggest, these are not images of sexual violence or despair but of workmanlike collusion in studio activity. They reveal beyond the isolated framing of the nude, the context and the agency through which that image is produced. The Studio: The Painting of a Nude is a quite remarkable, almost Brechtian, instance of this. Where, as a genre, the nude promotes untrammelled access to a naked body, the painter’s arm, turned towards us, bars entry to the room and the model behind. The paintwork is extraordinarily rich, varied and diverting. Only gradually do we come to read the entire scene as a mirror reflection. The painter has his back to the model, and paints her reflection, along with the further reflection of her back as it is revealed in a mirrored wardrobe at the rear of the room.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Camden Town Murder c.1909

Pencil on paper

248 x 200 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

By courtesy of the Witt Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London

Fig.21

Walter Richard Sickert

Camden Town Murder c.1909

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

By courtesy of the Witt Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London

This suggests the substitutions that undermine by overlaying the stable role of the male protagonist. His status, already uncertain as husband or murderer, already unsettling (as our surrogate ‘eyes’), is complicated if he also stands in for the artist and the woman for the body of painting itself.123 This is to allegorise the relations of painter and model, culture and nature, artist and Art, in traditional ways.124 But then, the artist is also not his (masculine) stand-in but his (feminine) creature – the woman/prostitute – at the mercy of the market and ‘a rough-tongued, hard-faced mistress’ who is Painting herself. In Sickert’s ‘perversity’, which could be figured as the tension between a bravura handling of surface and an implicitly sadistic treatment of his model in these pictures, it is Painting itself that is murdered and loved.125

Death

In her book Over her Dead Body, a study of the conjunction of femininity and death in art and literature, Elisabeth Bronfen asks how a representation can be both morbid and aesthetically pleasing.126 Or as Paul Konody put it in the Observer in 1912, how the spectator of these ‘unsavoury and sordid’ scenes was nevertheless obliged ‘to admire in Mr Sickert’s art that which he would turn away from with loathing in actual life’.127 Part of the answer is that the death we contemplate is not our own. As Walter Benjamin put it, ‘What draws the reader to the novel is the hope of warming his shivering life with a death he reads about’.128 And part of the answer is that it isn’t ‘real’. Only as representation can death be contemplated. Sickert trod a fine line – finer and more troubling for viewers in 1911 than for us – between death in the aesthetic – a couple of models, some studio props, a painterly and surprisingly decorative facture – and death in the newspapers (the brute fact of a prostitute’s throat slashed to the vertebrae in Camden Town).

Malcom Drummond 1880–1945

19 Fitzroy Street c.1913–14

Oil paint on canvas

710 x 508 mm

Laing Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Laing Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

Fig.22

Malcom Drummond

19 Fitzroy Street c.1913–14

Laing Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Laing Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

Charles Harrison has proposed that it is one of the marks of a modern picture that it addresses itself to a particular spectator.132 Where do we stand in relation to L’Affaire de Camden Town, or, as Victor Burgin once asked, who does this picture think you are? What is our connection, as viewers, to the witness in the room (what’s called in narrative the ‘internal focaliser’)? There is at least the possibility of something more companionable in the study, but the painting reinforces the sadistic mastery of the controlling gaze. Our position is even more compromising. We are the voyeurs. We take up what Degas and Sickert called the keyhole view, spatially and psychologically.133 He looms threateningly over her but we are the intruders who look unhindered at the most intimate part of her anatomy, and her blindness – her inability to interrupt or challenge that look – is absolute. Sickert’s space is visceral, subtly distorted, not perspectivally ordered and plain. The light sources come from different directions. The looming figure stands on a higher plane. The large area of busy wallpaper sets the whole thing off key.134 In the French tradition it was ‘obvious’ that Sickert’s nudes were prostitutes. Louis Vauxcelles, in a review of the earlier nudes, described Sickert’s handling of space and form as the consequence of multiple ‘taches’, a word meaning marks or spots but also blotches and stains.135 In Vauxcelles’s French prose it is possible to conflate a description of the paint surface with a comment on its referent. If the bourgeois interior is a space of seclusion from the public world, these bruised, stained bodies on dishevelled beds are commodities in their place of work. Sexual violence becomes an extreme, an intimate, version of the penetration of privacy that is their métier.

On the other hand, Sickert does not take up a moral position; does not render the nude mysterious; does not offer to give her meaning, but owns up to a voyeuristic perversity and compromises us in that too.136 What T.J. Clark has defined as ‘the nude’s most characteristic form of address’ was always ‘a dreamy offering of self, that looking which was not quite looking’; or, in place of her averted gaze, the spectator might be offered instead ‘a pair of eyes within the picture space: the look of Cupid or the jester’s desperate stare, the familiarity of a servant or a lover’.137 Both these options are blocked by Sickert. There is no ‘dreamy offering’ of self (the viewer’s guilt-free alibi), and no easy identification with a murderous surrogate (or one who is bereft).138 A viewer of either sex is likely to feel uncomfortable and unsafe: the nude is rendered as victim and flesh, the libidinal gaze of the voyeur is contaminated by sadism and guilt, and the ethical gaze of the witness is compromised by the forced perspective of the voyeur.

There is, however, both a moral detachment and a paradoxical resonance of colour and brushwork in L’Affaire de Camden Town that sets it apart from the narratives of fallen women in nineteenth-century painting and from the trope of the prostitute as an easy emblem of social, political or feminine corruption. The corpse is the ultimate in abjection, the waste that can never be recuperated, the body that is no longer an ‘I’.139 The Camden Town Murder paintings are paintings of death. But because they are paintings they are also the products of love and work, of a relation with two particular models in a studio mis-en-scène.140 Their understatement and self-conscious facticity remind us of that. Or as Sickert put it in another context: ‘The subject of painting is, perhaps, that it is not death. It is, perhaps, nothing more.’141

Notes

From one of a series of six lectures delivered at the Thanet School of Art between 26 October and 29 November 1934, edited by Paul Pelowski, in Sickert and Thanet: Paintings and Drawings by W.R. Sickert 1860–1942, exhibition catalogue, Ramsgate Library Gallery 1986. (The quotation is from the lecture of 16 November; the transcript is in the collection of Kent County Library, publisher of the exhibition catalogue.)

The murder and its aftermath appeared in newspaper headlines as ‘The Camden Town Murder’, ‘The Camden Town Murder Mystery’ and ‘The Camden Town Affair’. Four paintings (three, with one smaller variant) seem to have been exhibited with specific references to the murder in their titles. There are a number of associated drawings, one of them – a nude study for L’Affaire de Camden Town – inscribed, later, as ‘Study for Murder of Emily Dimmock in St. Paul’s Road, Camden Town’. These and related Camden Town interiors (such as Dawn: Camden Town c.1908–9) are discussed by Wendy Baron in Baron and Richard Shone (eds.), Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992. Baron is the doyenne of Sickert scholars and I am indebted both to her monograph (Sickert, Phaidon, London 1973) and to the Royal Academy catalogue, which includes illuminating essays by Richard Shone (‘Walter Sickert, the Dispassionate Observer’) and Anna Gruetzner Robins (‘Sickert “Painter-in-Ordinary” to the Music Hall’). Unlike Baron and Shone (but like Robins) I believe that it makes sense to single out for discussion those paintings and studies that are linked directly to the murder as an event, and to connect them to Sickert’s interest in Jack the Ripper.

It was not always a ‘third floor back’: sometimes it was a ‘first floor front’ (like the ‘parlour rooms’ where Emily Dimmock died). Marjorie Lilly accompanied Sickert on some of his searches for the right location: ‘As time went on he seemed to need a fresh garret for almost every picture, as if each one afforded him a separate sharp experience that must be concentrated on a single canvas ... we rapped on endless doors, dived under greasy curtains in narrow halls, climbed rickety stairs to third floor backs ... At last, however, he came upon his treasure trove. A crooked room at the top of a crooked house in Warren Street ... I fear that I failed to appreciate the significance of this grisly chamber. All I saw was a forlorn hole, cold, cheerless ... All he saw was the contre-jour lighting that he loved, stealing in through a small single window, clothing the poor place with light and shadow, losing and finding itself again on the crazy bed and floor. Dirt and gloom did not exist for him; these four walls spoke only of the silent shades of the past, watching us in the quiet dusk’ (Marjorie Lilly, Sickert: The Painter and his Circle, Elek, London 1971, pp.42–3).

Rutter is cited by Quentin Bell, Bad Art, Chatto & Windus, London 1989, p.91; Bell’s own reference to Sickert’s ‘bamboozlement’ is from his review of ‘Sickert at the Tate Gallery’, Listener, 2 June 1960, p.40.

Roger Fry, ‘Mr Walter Sickert’s Pictures at the Stafford Gallery’, Nation, 8 July 1911, p.536; Fry, Prefatory Note to the Contemporary Art Society exhibition at Manchester Corporation Art Gallery, from a clipping in Sickert’s scrapbook in the Sickert Collection, Islington Public Library, p.40.

Walter Sickert, ‘The Language of Art’, New Age, 28 July 1910, quoted from Osbert Sitwell (ed.), A Free House! or The Artist as Craftsman: Being the Writings of Walter Richard Sickert, Macmillan, London 1947, p.89.

Anna Gruetzner Robins, Walter Sickert: Drawings, Scholar Press, Aldershot 1996, Appendix: ‘Sickert’s 1911 and 1912 Carfax Exhibitions: A Partial Reconstruction’. I am grateful to Anna Robins for discussing Sickert with me and for the loan of her typescript. We had arrived independently at the conviction that Sickert’s interest in Jack and Ripper constituted one of the subtexts for the Camden Town Murder paintings, but we treat the issue rather differently.

Sickert often gave paintings titles only after they were completed. This would have been even more likely with drawings which had an independent existence only when exhibited or sold. But I shall argue that The Camden Town Murder titles were not an afterthought, a publicity peg or a piece of mischief but a considered reference to the murder itself, which was the motor for these images, temporarily focusing a wider interest in two-figure interiors.

Stella Tillyard has argued this in a stimulating essay, ‘The End of Victorian Art: W.R. Sickert and the Defence of Illustrative Painting’, in Brian Allen (ed.), Towards a Modern Art World, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 1995. I am indebted to her in several respects, despite differing from her conclusions. She sees the murder paintings and their studies as a narrative sequence ‘plotted at three interconnected levels’, so that the narrative runs from transaction (the drawing of the couple seated in bed, no.268 in Baron 1973), to engagement (La Belle Gâtée), to the deed just done (The Camden Town Murder), to the murderer’s final glance before he leaves (L’Affaire de Camden Town). (In fact I think the slimmer, clean-shaven man in the first drawing is not the same model as in the others and looks remarkably like Sickert.) Tillyard sees the story of the murder itself as inseparable from the wider narrative of social and moral degeneration (of which crime was a symptom), which was itself part of the millenarian mood of the fin-de-siècle. This is undoubtedly how – in more conservative quarters – the pictures were read. But I think that Sickert is more equivocal than this and that that is what keeps his paintings alive. As images of death these are resolutely modern (banal, inconsequential) with the detachment of the newspaper.

On titles see John Fisher, ‘Entitling’, Critical Inquiry, vol.11, no.2, December 1984, pp.286–98; Gérard Genette, ‘Structure and Functions of the Title in Literature’, Critical Inquiry, vol.14, no.4, Summer 1988, pp.692–720; and now – surely the definitive word – John Welchman, Invisible Colors: A Visual History of Titles, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 1997. Genette sees the function of titles as designation (of the work), indication (of the content) and seduction (of the consumer): ‘A good title should say enough to excite curiosity, and little enough not to saturate it’ (p.718). Although a painting is not a mass-produced commodity like a book, a provocation of Sickert’s murder titles was useful publicity for the Camden Town Group in 1911. But it would be a mistake to see Sickert’s ‘capricious’ way with titles as nothing other than his own version of Whistler’s symbolist exit from subject matter into an insistence on the primarily formal properties of the work. Sickert, almost uniquely, wanted to retain some sense of narrative at the centre of a painting of modern life. Fisher insists: ‘Not all artworks are titled. Not all artworks need to be titled. But when an artwork is titled, for better or for worse, a process of interpretation has inextricably begun’ (p.298). Welchman points out that before the 1860s most titles were denotative, broadly unequivocal and unmischievous. ‘Modern’ titling practices he sees as divided between the (traditionally) decorative, the connotative (stretching to the allusive and even, with dada and surrealism, the absurd) and the ‘conclusively modernist practice of advertising the absence of a title through the description “Untitled”’ (or through numbering or other non-referential designations) (pp.2, 7–8). He points to the necessary intertextuality effected between the press photograph and text (whether title, caption or article), but this was already anticipated in the nineteenth-century illustrated journalism from which, along with newspaper headlines and music hall songs, Sickert took his cue.

Walter Sickert, ‘The Whistler Exhibition’, Burlington Magazine, July 1915, in Sitwell (ed.) 1947, p.35.

Hilton Kramer, ‘Justice to Walker Sickert’, Modern Painters, vol.5, no.4, Winter 1922, p.13. Kramer points out that you ‘can’t tell’ that the woman in the painting is dead, which is true, given the approximations of Sickert’s handling and the fact that ‘Camden Town Murder’ is no longer a topical catchphrase. It is beside the point, however, insofar as Sickert invited his first audience to respond to these paintings in terms of its familiarity with this and related crimes of sexual violence: the Morning Post and his other reviewers knew well enough that this was a corpse.

Simon Watney, in English Post-Impressionism, Studio Vista, London 1980, also insists, pace Dr Baron, that Sickert’s titles are ‘indispensable guides to our understanding of his art’ signifying ‘a desired angle of viewing which ranges from the ironic ... to the frankly quotidian’ (p.138). Kaja Silverman has discussed in the case of Courbet’s Origin of the World – a painting with something of the same sexual focus as L’Affaire de Camden Town – how the title pulls the image into a different semantic space: it ‘isolates that representation from the all-too-familiar beaver shots with which it might seem otherwise indistinguishable and obliges it to circulate as a transgressively maternal image – an image that shows the mother as only a prostitute “should” be seen and which in the process forces a redefinition of both categories’ (Kaja Silverman, ‘Liberty, Maternity, Commodification’, in Mieke Bal and Inge Boer (eds.), The Point of Theory: Practices of Cultural Analysis, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 1994, p.26).

Lou Klepac (introductory essay, The Drawings of Walter Richard Sickert, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth 1979, p.11) says this begins with the Venice paintings of 1903, when he first sees the possibilities of literary painting and Charles Keene, always admired, begins to have an influence on the composition of figures in interiors imbued with a certain social and psychological intensity.

Walter Sickert, ‘A Critical Calendar’, English Review, March 1912, quoted in Baron and Shone (eds.) 1992, p.213: ‘A painter may tell his story like Balzac, or like Mr. Hichens. He may tell it with relentless impartially, he may pack it tight, until it is dense with suggestion and refreshment, or his dilute stream may trickle to its appointed crises of adultery, sown thick with deprecating and extenuating generalisations about “sweet women” ... our insular decadence in painting can be traced back ... to puritan standards of propriety. If you may not treat pictorially the ways of men and women, and their resultant babies, as one enchained comedy or tragedy, human and de moeurs, the artist must needs draw inanimate objects – picturesque if possible. We must affect to be thrilled by scaffolding, or seduced by oranges.’

Walter Sickert, ‘The Post-Impressionists’, Fortnightly Review, January 1911, in Sitwell (ed.) 1947, p.197. Henry James, The Portrait of a Lady (1881), Penguin, Harmondsworth 1963, p.76: ‘[Isabel Archer] found the Misses Molyneux sitting in a vast drawing-room ... in a wilderness of faded chintz.’ Perhaps Sickert thought of the Misses Molyneux, sisters to Lord Warburton, as characters in his ‘Goosocracy’.

Cited in Penelope Curtis, ‘Introduction’, in W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, Liverpool 1989, p.6.

Walter Sickert, ‘The Language of Art’, New Age, 28 July 1910, in Sitwell (ed.) 1947, p.89. See also ‘The Royal Academy’, English Review, August 1912, ibid., p.74, on the tiny figure of a thatcher, applied, ‘like a postage stamp’, on a roof of a far off cottage in a painting by Millet: ‘Millet was giving here just that something that only the pencil or the brush can give, an emotion whose bouquet will not survive decanting from the skin of painting into that of letters.’

There were anonymous double page spreads in the Illustrated Police Budget and the Illustrated Police News on the same day: 21 September 1907, pp.8–9.

Daily Telegraph, 22 June 1911, p.8. The review acknowledges that Sickert’s paintings are ‘bold and masterly of their kind’ but wonders ‘how this valiant young advanced guard can keep up their spirits in the depressing atmosphere created by such a designation as “The Camden Town Group”’.

Or Conrad: see for example the Illustrated London News, 24 February 1912 [in Sickert’s cuttings book, p.85]: ‘If Mr Conrad went to the back bed-sitting-rooms of Camden Town for his drama, his reporting would match Mr Sickert’s; it has the same genius for the instantaneous selection of the inevitable detail’; see also the Observer, 9 March 1913, on Sickert’s etchings at the Carfax Gallery: ‘Of course, the puritanical mind may object to that series of sordid and gross bedroom scenes suggested by the revolting details of the Camden Town murder. It would object to them, as it objected to Flaubert’s “Madame Bovary”.’

John Rothenstein, Modern English Painters, vol.1, revised edn, Macdonald and Jane’s, London 1976, p.53: ‘How poorly, even at the height of his powers, he could on occasion draw is apparent not only in acknowledged failures, but in such a widely admired picture as The Camden Town Murder ... The torso of the recumbent woman, a confusion of clumsy planes which fail to describe the form, would do no credit to a student; the hands of both woman and man are shapeless. This picture shows in its extreme degree the innate weakness as a draughtsman and summariness as a designer against which he fought a lifelong, but in the main a glorious battle’; the next page refers to ‘the wretched Camden Town Murder’.

L’Affaire de Camden Town is in a private collection; I am most grateful to its owner, who kindly granted access to it.

Bram Dijkstra, ‘Dead Ladies and the Fetish of Sleep’, Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siècle Culture, Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1986, pp.50–63.

Wendy Baron (1973, p.84) points out that there are echoes of Bonnard in Sickert’s nudes painted in France in 1904–5, and that Sickert had many opportunities to see his work – they shared private collectors (including André Gide) and a dealer (Bernheime-Jeune). On the expressive deployment of figural and spatial arrangements in paintings of the bourgeois interior, see Susan Sidlauskas, ‘Psyche and Sympathy: Staging Interiority in the Early Modern Home’, in Christopher Reed (ed.), Not at Home: The Suppression of Domesticity in Modern Art and Architecture, Thames and Hudson, London 1996, pp.65–80.

Basil Hogarth (ed.), Trial of Robert Wood (The Camden Town Case), William Hodge, London and Edinburgh 1936, p.1. It had apparently faded from view by the time that George Orwell came to write his satirical essay on the ‘Decline of the English Murder’, since although he dated our ‘great period in murder, our Elizabethan period, so to speak’ to the years between 1850 and 1925 the Camden Town Murder is not one of the nine cases of ‘murderers whose reputation has stood the test of time’; reprinted in Shooting an Elephant and Other Essays, Secker and Warburg, London 1950. (On the other hand, although he dated it, perhaps by mistake, to 1919, he noted that there was ‘another very celebrated case which fits into the general pattern but which I had better not mention by name, because the accused man was acquitted’, p.197). The Times, with far less interest in the trial than the popular dailies, still carried reports on 13, 14, 17 and 21 September; 1, 7, 8, 15, 16, 22, 23 and 29 October; 7, 13, 14, 15, 21, 23, and 29 November; and on 5, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18 and 19 December. The Daily Mirror front page featured the trial on several issues running during December 1907.

The account that follows is drawn from the contemporary press and from Hogarth (ed.) 1936. This includes transcripts from the trial together with an introduction and two appendices – Sir Hall Caine’s ‘The Law and the Man: A Psychological Study of the Great Trial’ and Robert Wood’s letter to his brother at the end of the first day – as well as a useful chronology of events. See also Edward Marjoribanks, The Life of Sir Edward Marshall Hall, Victor Gollancz, London 1930; and David Napley, The Camden Town Murder in the series Great Murder Trials of the Twentieth Century, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London 1987.

According to evidence from the police surgeon Dr John Thompson, the carotoid artery, windpipe, jugular vein and larynx had been severed cleanly down to the dorsal vertebrae; the weapon was never found. His statement was reported in the Police Budget, 16 November 1903, p.3, and is included in Hogarth (ed.) 1936, p.6.

Hogarth (ed.) 1936, p.41. Wood had opportunity, a false alibi (dramatically exposed) and a poor demeanour in the witness box; on the other hand the evidence against him was contradictory and circumstantial, and the judge, in his summing-up, suggested ‘reasonable doubt’. The jury returned a verdict of ‘not guilty’ in fifteen minutes. Hogarth’s analysis of the case acknowledges that the prosecution was woven on ‘a web of circumstance’ gossamer thin, but concludes that Wood escaped lightly the damning inferences of the Crown witnesses and his own duplicity.

See for example Beth Kalikoff, Murder and Moral Decay in Victorian Popular Literature, UMI Research Press, Ann Arbor 1986. She cites one of Henry Mayhew’s informants in London Labour and the London Poor, who observed that notorious murders were ‘great goes’ in street literature.

Walter Sickert to Nan Hudson, from 6 Mornington Crescent [1907], Ethel Sands Papers, Tate Archive, TGA 9125: ‘This is to tell you I have got entangled in a bunch of a dozen or so interiors on the first floor here. A typical lodgings first-floor. If you are in London any day and could come I should so like to show you a set of “studies of illumination half-done [sic, no closing”]. I am very much interested and shall stay till they are done. A little Jewish girl of 13 or so with red-hair and a nude alternate days.’

Wendy Baron is confident that Sickert would have followed reports of the Camden Town murder and trial in the press. Lilian Browse quotes a description of Sickert’s sitting room in Brighton from a visitor who found ‘newspapers covering the floor over which I was requested to step carefully; they were not to protect the carpet from paint as I at first supposed, but spread there in case he wanted to refer to certain articles in them he had found of special interest, and during lunch he suddenly jumped up and searched for one he wanted to read to me’ (Browse 1960, p.29, from a letter written to her by Miss Elfrida Lucas).

Baron, in Baron and Shone (eds.) 1992, p.210: ‘There is an oral tradition (told to the compiler by Rex Nan Kivell of the Redfern Gallery, London) that Sickert employed Robert Wood ... as his model ... Perhaps the tradition was partially distorted in the telling: for example, if not Wood, Sickert’s model could have been another of the male protagonists in Emily Dimmock’s history, for example, Bertram Shaw the railwayman’. This is an intriguing idea, but it is not borne out by a contemporary description of Bertram Shaw as ‘a thin-featured, pale faced, slightly-built young man’ (Lloyd’s Weekly News, 22 September 1907, p.7).

As conveyed in the press: see for example the News of the World, 22 September 1907, p.9. Napley (1987, p.29) gives a contemporary description of Wood’s ‘long delicate hands and tapering fingers; deep-set cavernous eyes and glistening eyeballs’, high cheekbones and broad, twitching mouth.

Sickert’s ‘Mesopotamia-Cézanne’ (a review of Clive Bell’s Art, in New Age, 5 March 1914, pp.312–13) dismisses Lombroso’s tables of ‘genius’ on which his conclusions are based: ‘When we find Lombroso deducing immense and far-reaching laws on genius from tables in which Henner, and others still less consequent, stand for examples of genius in panting, we are inclined to suspect that Lombroso is perhaps only a high-class and extremely entertaining Mr. Gribble.’ (Anna Gruetzner Robins has identified this reference: Theodore Graham Gribble was the author of The 50 Centimetre Slide-Rule as applied to Tracheometry and Curve-ranging, 1912.) Lombroso was nevertheless an influential writer on deviance and degeneration, one of the founders of post-Darwinian criminal anthropology. He further systematised, and made scientifically respectable, the correlation between physical appearance and disposition of character which (though it goes back to Aristotle) was at the heart of Victorian phrenology and physiognomy. In L’Uomo delinquente (1876), translated as Criminal Man (1891), Lombroso claimed to have identified an atavistic criminal type with a tendency to ‘outstanding ears, abundant hair, a sparse beard, enormous frontal sinuses and jaws, a square and projecting chin, broad cheekbones’. See William Greenslade, Degeneration, Culture and the Novel, 1880–1940, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994, p.92. The profile of the male protagonist in L’Affaire de Camden Town would slip easily into Lombroso’s imagery of ‘criminal types’, and approximates to that of the prisoner in the dock in the Punch cartoon (22 February 1896), reproduced in Greenslade, p.95. See also Mary Cowling, The Artist as Anthropologist: The Representation of Type and Character in Victorian Art, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989.

Letter from Ethel Sands to Nan Hudson, Sands Papers, Tate Archive, TGA 9125, quoted in Wendy Baron, Miss Ethel Sands and her Circle, Peter Owen, London 1977, p.98, where it is assumed to date from about 1912. Sickert was trying to dissuade them from taking themselves and their own surroundings as pictorial subject matter. ‘Of course he hated mine, and though he tried to be nice and helpful, said I must stop painting interiors and still life for a bit. There I think he’s right. Suggested I should go and do a prize fighter he’s having at Granby St. next week with a naked lady sitting on his knee! Rather a tempting offer!’

Illustrated Police Budget, 30 November 1907, p.2 (in the same issue as a continuing account of ‘The Camden Town Murder Mystery’).

Dimmock’s body was wrongly described in the caption to the Illustrated Police Budget image as ‘otherwise mutilated’.

Baron’s entry on The Camden Town Murder, in Baron and Shone (eds.) 1992, p.208, makes this point, crediting Shone (Walter Sickert, Phaidon, Oxford 1988, p.51) with drawing attention to a famous music hall song of Tom Costello’s, ‘At Trinity church I met my doom’, which includes the lines ‘Now we live in a top back room / Up to my eyes in dept for renty’.

Police Illustrated News, 12 October 1888, reproduced in Judith Walkowitz, ‘Jack the Ripper and the Myth of Male Violence’, Feminist Studies, vol.8, no.3, Fall 1982, p.553.

Sitwell (ed.) 1947, pp.xxxviii–xxxix. The Tichborne case, which turned on the true identity of a claimant to Tichborne baronetcy, had made newspaper headlines when Sickert was eleven. There is a small collection of Tichborne ephemera, assembled by Sickert and in his possession at his death, in the library at Lincoln’s Inn (ms 827). (Sickert was rumoured to be planning a book on him and it includes pamphlets, books, photographs and a signed framed photograph.) Perhaps there was once a parallel file on Jack the Ripper, the other ‘immutable monument’. Sitwell believed that apart from its ‘intrinsic and abiding horror’, the story of the Ripper interested Sickert because he thought he knew the identity of the murderer (the mysterious veterinary student who had preceded him as a tenant in one of his lodgings). Sickert was likely to have been mistaken, but was apparently convinced that he had written the name in the margin of a French edition of Casanova’s memoirs lent to William Rothenstein. He tried to get it back, but it had been lent to Albert Rutherston (Rothenstein’s brother), who lost it in the blitz (pp.xxxix–xl).

Lilly 1971, all quotations from p.15. In Poe’s The Purloined Letter, Auguste Dupin explains that part of his method is to ‘fashion the expression of my face, as accurately as possible, in accordance with the expression of [the perpetrator’s], and then wait to see what thoughts or sentiments arise in my mind or heart, as if to match or correspond with the expression’ (quoted in Wendy Lesser, Pictures at an Execution, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1993, pp.56–7). If this was what Sickert was doing, it was not in order to give character and motive to his painted physiognomies in a traditional way. We get some sense of them, but not much. We are blocked by the opacity and understatement of the facture. Charles Keene used to keep hanging on pegs in his studio the costumes he wore to pose for the characters in his drawings (Sitwell ed. 1947, p.xxiv). According to Clive Bell, Sickert was ‘naughty by nature and he never ceased to be an actor’: Old Friends: Personal Recollections, Chatto and Windus, London 1956, p.15. He was famous as a dandy and a mimic (his ‘Roger Fry’ was particularly good). Retrospectively and perhaps ironically he titled a 1907 self-portrait The Juvenile Lead: see Baron and Shone (eds.) 1992, p.194.

Lilly 1971, pp.15–16: ‘When the handkerchief had served its immediate purpose it was tied to any doorknob or peg that came handy to stimulate his imagination further, to keep the pot boiling.’ Even the landlady respected the handkerchief, and left it alone when she came in to clean. There is a suggestion of the red neckerchief in The Camden Town Murder painting at Yale.

Denys Sutton, Walter Sickert: A Biography, Michael Joseph, London 1976, p.149. No doubt Sickert’s well-documented obsession, together with his exploitation of the Camden Town Murder for a series of paintings, encouraged those hypotheses that have in the last twenty years identified Sickert as Jack the Ripper or his accomplice. See for example Stephen Knight, Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, Collins, London 1977, which compares Sickert’s painting La Hollandaise with police photographs of the murdered and mutilated Mary Kelly; and Jean Overton Fuller, Sickert and the Ripper Crimes: An Investigation into the Relationship between the Whitechapel Murders of 1888 and the English Tonal Painter Walter Richard Sickert, Mandrake, Oxford 1990. Knight’s and Fuller’s theories rely on information provided by Sickert’s supposed illegitimate son, Joseph Sickert (Fuller claims that Mary Kelly had been engaged as a nanny and blackmailed Sickert after she left). Baron deals briskly with the false claims and premises on which these arguments are based (Baron and Shone eds. 1992, p.213).