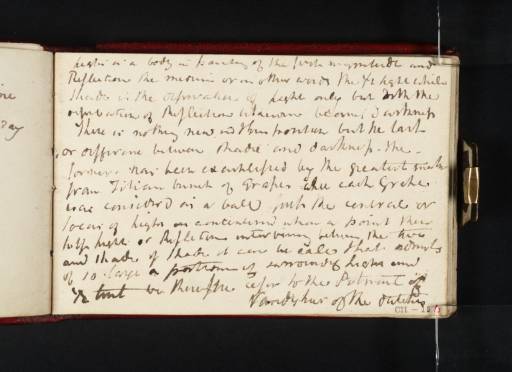

Joseph Mallord William Turner Notes on Reflection and Refraction, for Perspective Lectures (Inscription by Turner) c.1808

Joseph Mallord William Turner,

Notes on Reflection and Refraction, for Perspective Lectures (Inscription by Turner)

c.1808

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Folio 15 Recto:

Notes on Reflection and Refraction, for Perspective Lectures (Inscription by Turner) circa 1808

D06749

Turner Bequest CII 15

Turner Bequest CII 15

Inscribed by Turner in ink (see main catalogue entry) on white wove paper, 76 x 115 mm

Inscribed by John Ruskin in red ink ‘15’ bottom right

Stamped in black ‘CII 15’ bottom right

Inscribed by John Ruskin in red ink ‘15’ bottom right

Stamped in black ‘CII 15’ bottom right

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

References

1909

A.J. Finberg, A Complete Inventory of the Drawings of the Turner Bequest, London 1909, vol.I, p.267, CII 15, as ‘Some remarks about light and shade’.

1969

John Gage, Colour in Turner: Poetry and Truth, London 1969, pp.198–9, 271 note 1.

1992

Maurice Davies, Turner as Professor: the Artist and Linear Perspective, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1992, pp.53, 108 note 95.

1994

Maurice William Davies, ‘J.M.W. Turner’s Approach to Perspective in his Royal Academy Lectures of 1811’, unpublished Ph.D thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, London 1994, p.287.

.

Finberg transcribed only extracts from these notes, which continue on folios 16, 17, 19, 20 and 28 (D06751, D06753, D06756, D06758, D06774). Although not written by Turner as a continuous sequence they seem to be intended to be read (or heard) as such and for convenience are given together here, in the reading published by John Gage:.

Light is the body in painting of the first magnitude and | Reflection the medium or in other words the half light while | shade is the deprivation of light only but with the | deprivation of Reflection likewise it becomes Darkness | There is nothing new in this position but the last | or difference between shade and darkness. The | former has been accomplished by the greatest masters | from Titian’s bunch of grapes where each grape | was considered as a ball just the central or | focus of light was concentrated | upon a point then | half light or Reflections intervening between the two | and shade if shade it can be called that admits | of so large a portion of surrounding light and | ½ tint. We therefore refer to the Portrait of | Vandyke of the Dutchess [continued on folio 16] of Cleveland (dark Green) as the most instructive | for the advancement of Study. to the greatest | part of the Globe on which | the figure leans in the | character of St Agnes partook partly of | half light a central | speck opposite to the | sapphire ray of light and the reflection opposite | the shadowd part ... between from | which is resting upon a base from which | the light strikes it the ball receives a | reflected light another but lower in line | opposing it so that when I [? have] to define the | light and shade it would be right to admit a reflecting and reflective light. [continued on folio 17] Refracted lights are those received by all | bodies, but most so by polished ones from all | surrounding objects both of light and shade | and of course where refraction is concerned | shade must become more circumscribed | Refracted lights give clearness and by their | help objects can be more defined. by a | judicious introduction but they destroy | force. Rembrandt is a strong instance | of caution as to reflected light and | Correggio to refracted light. Two instances | of the strongest class may be found in the | celebrated pictures of the Mill and La Notte. [continued on folio 19] The Mill has but one light, that is to say upon | the Mill, for the sky, altho a greater body of | mass is reduced to black and white, yet is not | perceptible of receiving [the] ray by any indication of |form, but rather a glow of approaching light | . But the sails of the mill are touched with the | incalculable ray, while all below is lost in in | estimable gloom without the value of reflected | light, which even the sky demands, and the | ray upon the Mill insists upon, while the | ½ gleam upon the water admits the reflection of the | sky. Evanescent twilight is all reflection but | in Rembrandt it is all darkness and gleam of light | reactive of reflection. Refractions [are] occasioned | aerially. [continued on folio 20] The Notte is all light and shade in Darkness. | But as a solitary instance from a great master | may appear contrived, and caution of allowing | his knowledge in light and shade, let me draw | another instance of that knowledge in another | picture the Cradle, here, where Reflections &c | become only powerful in a concentrated | ray; and Refraction [and almost Reflection inserted] ceases except in bodies that | admit the first light. He becomes the master of | artificial light and shade, let me suppose it | be understood as those lights that are artificial | and not those beams that give light vigour | and animation to the uneventful. Their effect | in an abstracted sense is as distinct as this [continued on folio 28] appearance. Nature it would be wrong to say | as we can but know but one: the rays of the | sun strike parallel, while the candle | angular. One destroys shade, while the other | increases it; and as reflection and refraction | are increased by the influx of light, so are | they concentrated by an excess of shadow |, produced by the light becoming a focus |. The art of the Picture therefore is only and | properly light and shade; the greatest | shade opposed to the greatest light, as | ... the Mill is otherwise than the opposition of the light depicted

These notes are preparatory for Turner’s lectures as Professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy, especially Lecture 5 which dealt with reflection and refraction.1 As noted by Gage, the opening passage is based on commentary by Joshua Reynolds to C.A. Du Fresnoy’s De Arte Graphica.2 Turner refers to several pictures by Old Masters. Titian’s ‘bunch of grapes’ is unidentified. As Gage recognised, from Turner’s description Van Dyck’s portrait must be Rachel de Ruvigny, Countess of Southampton, as Fortune (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne);3 Turner’s interest in its reflecting globe parallels his drawings of reflections in metal and glass balls, also made for his lectures(for example Tate D17147; Turner Bequest CXCV 176). Turner then compares Rembrandt’s Mill (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC) and Correggio’s Nativity (‘La Notte’) (Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden). The ‘Cradle’ is The Holy Family at Night by a close follower of Rembrandt (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), then owned by the connoisseur Richard Payne Knight who lent it to the British Institution in 1808 and commissioned a companion picture by Turner, The Unpaid Bill, or the Dentist Reproving his Son’s Prodigality which was shown at the Royal Academy the same year (collection of the Schindler Family).4 The comic-satirical narrative of Turner’s response might be in keeping with his critique of the ‘contrived’ and ‘artificial’ character of this particular ‘Rembrandt’ while it certainly contrasts the effects of sunlight to the other’s candlelight; however, Turner seems to have taken another picture in Payne Knight’s collection as his main point of reference.5

David Blayney Brown

December 2009

Gage 1969, p.271 note 2; the source is in Edmond Malone ed., The Works of Sir Joshua Reynolds, 2nd ed. London 1798, note XL.

Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, revised ed. , New Haven and London 1984, pp.61–2 no.81 (pl.91). The Unpaid Bill and The Holy Family at Night were exhibited together at Tate Britain in 2009; see David Solkin ed., Turner and the Masters, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2009, pp.148–9 reproduced in colour pls.41, 42.

How to cite

David Blayney Brown, ‘Notes on Reflection and Refraction, for Perspective Lectures (Inscription by Turner) c.1808 by Joseph Mallord William Turner’, catalogue entry, December 2009, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www