Joseph Mallord William Turner Interior of St Giles's Cathedral: Study for 'George IV at St Giles's, Edinburgh' 1822

Image 1 of 2

Joseph Mallord William Turner,

Interior of St Giles's Cathedral: Study for 'George IV at St Giles's, Edinburgh'

1822

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Folio 33 Verso:

Interior of St Giles’s Cathedral: Study for ‘George IV at St Giles’s, Edinburgh’ 1822

D17559

Turner Bequest CC 33a

Turner Bequest CC 33a

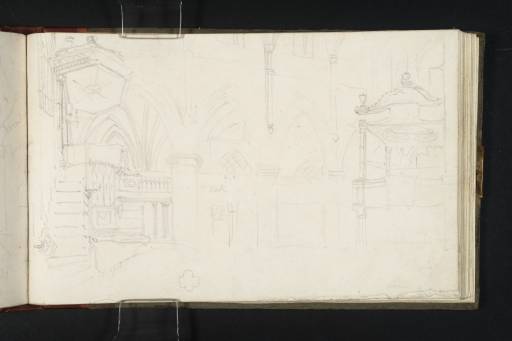

Pencil on white wove paper, 114 x 187 mm

Inscribed in pencil by Turner ‘oak’ centre

Blindstamped with the Turner Bequest stamp bottom right

Inscribed in pencil by Turner ‘oak’ centre

Blindstamped with the Turner Bequest stamp bottom right

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

References

1909

A.J. Finberg, A Complete Inventory of the Drawings of the Turner Bequest, London 1909, vol.I, p.611, CC 33a, as ‘Interior of St. Giles Cathedral.’.

1975

Gerald Finley, ‘J.M.W. Turner’s Proposal for a “Royal Progress”’, The Burlington Magazine, vol.117, January 1975, pp.30 figure 24, 35 note 10.

1981

Gerald Finley, Turner and George the Fourth in Edinburgh 1822, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1981, pp.37, 82–3, [128] reproduced as ‘Interior of St Giles with pulpit and royal pew. See oil painting in the “Royal Progress” cycle, George IV at St Giles’s, Edinburgh (Tate Gallery, no.2857) (Plate 17)’.

1984

Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, revised ed., New Haven and London 1984, p.153.

1992

Maurice Davies, Turner as Professor: The Artist and Linear Perspective, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1992, pp.90–1.

Turner was present when the King attended service at St Giles’s Cathedral on 25 August 1822, managing to get a ticket for the event along with artists, William Collins, David Wilkie and William Allan.1 As was frequently his approach for recording the ceremonial events of George IV’s visit to Scotland (see George IV’s Visit to Edinburgh 1822 Introduction) he combined direct observation of the event with a separate study of the location. His four pages of sketches at St Giles’s – two views of the interior (this page and folio 34; D17560) and two pages of architectural details (folios 32 verso and 33; D17557, D17558) – show the church without congregation. This suggests that Turner did not make drawings during the event, but witnessed the service, making a separate visit to St Giles’s to draw the space which he could later populate with characters from his memory and imagination when he came to making an oil painting of the subject: George IV at St Giles’s, Edinburgh, circa 1822 (Tate N02857).2 The composition of the oil is number ‘15’ in Turner ‘Royal Progress’ sequence (see King at Edinburgh sketchbook inside back cover; Tate D40980). Drawing during the service was probably prohibited, certainly frowned upon.

Turner’s presence at the service (and elsewhere) was recalled by Wilkie,3 and is attested by his lively and detailed painting of the subject, which nevertheless takes liberties with the facts, notably the crowded aisles which Mudie insists were ‘kept entirely clear’.4 Whether Turner made his sketches before or after the service is not known, and different accounts give conflicting statements.5 However, it would perhaps have been difficult for the artist to make these sketches which show the cathedral almost empty and would have required him to stand and sketch for some duration in several locations, during the morning of the service. John Prebble describes how on 25 August the church, which opened its doors at 7am, was full by 9 o’clock, over two hours before the King arrived, and that as the congregation left a christening service began,6 affording Turner little opportunity to draw that morning. Although it is possible that he could have visited the church before the day of the service (the King’s attendance was confirmed on 21 August),7 the few sketches that he made of the interior indicate, by the time clearly spent on them and their similarity in viewpoint to the resulting painting, that Turner had decided by the time he came to make them what his composition would be, suggesting that he had already witnessed the event.8 Furthermore, the combination of elements from both sketches in the resulting oil suggests that Turner may even at this early stage have conceived of the perspectival trickery that he was to employ in that work (see folio 34).

George IV’s belated decision to attend service at St Giles’s Cathedral was seen as an important event for the people of Scotland; as Jane Grant reported in a letter to her mother, the act would ‘do more than any other thing to make him popular’.9 For Turner, it provided an opportunity to study the appearance of the King at length, and allowed him to combine his expertise in depicting the complex perspective of church architecture with a modern history subject. The religious nature of the occasion would fit well into his idea for a ‘Royal Progress’ that also contained royal, naval, historic and military subjects (see King at Edinburgh sketchbook, Tate D40979, D40980; Turner Bequest CCI 43a, Inside Back Cover). It might have proved to be the work to win the artist royal approval and his first commission. In the event Turner did make an oil painting of the subject, the most finished of his four 1822 Scottish subjects, making a genre scene that did not attract royal approval and, Finley speculates, may have lost him a possible print commission.10

The King was a passive participant in the service in which he was just another member of the congregation, albeit a highly honoured one, privileged by his own special pew and a mention in prayer. The single gesture the King had planned, other than observing the service with ‘affecting humility’ – to place a sealed packet endorsed ‘One Hundred Pounds from the King’ in the Poor’s Plate – was denied by a church official who had removed the plate, assuming that a dish of dirty coins would be an offensive sight to the sovereign.11 With no single moment of action, therefore, Wilkie lost interest in the event and Turner was left with the King in his pew as the only viable subject. Turner’s two sketches of the church interior, both showing the pulpit and pew, indicate that he had reached this decision by the time he came to make the sketches.

Turner took his two views from the north side of the nave, standing at the east end for one of the sketches and moving further towards the middle of the north aisle for the other. Some of his studies of architectural details were also made from these positions, although he must have moved around the cathedral to make other sketches.

The present page, used with the sketchbook inverted, is the most finished and detailed of the two views that Turner made of the interior of St Giles’s Cathedral, although it is not the most closely related composition to his oil painting of the King at St Giles’s. Taken from the middle of the north aisle, the drawing shows the nave and south aisle beyond, framed at the left by the pulpit and at the right by the royal pew which is raised up to the gallery level almost in line with the pulpit opposite. There is a curved set of steps leading up to the pulpit which has a hexagonal canopy above it, and is occupied in the finished oil by a rather gaunt and balding Reverend David Lamont. The royal pew, used on this day for the first time by a reigning monarch, was built in the 1780s by architect James Craig ‘in the Goth. stile’ [sic].12 It is shown here is some detail with its crown-shaped canopy (details of which are repeated on folio 32 verso), decorated pillars and curved wooden sides. There is a slightly more diagrammatic sketch of the pew from a different angle on folio 33, this time apparently occupied. The two items, representing in this depopulated sketch the twin authorities of church and monarchy, are drawn in careful but economic detail, as are the fan vaulting that creates a complex pattern seen through the arches and the decoration of the ‘oak’ parapet of the gallery. Turner, however, has saved time by drawing only half of the pattern on the pulpit’s canopy (the other visible half being identical) and leaving most of the gallery parapet blank. There is a blank area at the bottom of the page which, we note from the oil painting, should be taken up with the side of the box pews. A rosette shape drawn in this section seems not to belong to the pews, which were simply panelled though not adorned, but perhaps to the decoration of the gallery; a similar shape is observed above, just to the right of the pulpit. Just above this to the left is a curve that marks a round or oval table in front of the pews and to the right of the pulpit where several black-robed ministers sit in the painting.

Although it did not form the compositional basis of the oil painting, this drawing did provide most of the details. The sketch on folio 34 has a more diagrammatic quality, leaving blank or simplifying features that are shown on the present drawing. Additional sketches of details were made across folios 32 verso and 33, with parts of columns, pillars, vaulting, windows, and the decoration of the royal pew.

Thomas Ardill

October 2008

John Prebble, The King’s Jaunt: George IV in Scotland, August 1822 ‘One and twenty daft days’, Edinburgh 1988, p.323.

While Finley is cautious in his statement that Turner made his drawings ‘either before of after the service’, John Prebble suggests that Turner made them on an earlier occasion, writing that he ‘had visited the church several times’, and Katrina Thomson writes that they ‘were apparently drawn soon after Turner had observed the service’. Finley 1981, p.23; John Prebble 1988, p.323; Katrina Thomson, Turner and Sir Walter Scott: The Provincial Antiquities and Picturesque Scenery of Scotland, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh 1999, p.98.

Considering that Wilkie’s first idea of which part of occasion to paint – the King’s donation to the Poor’s Plate – was scuppered when at the last moment the plate was removed (Prebble 1988, p.323), Turner may appreciated that it was a waste of time to plan a composition like this before he actually saw the event.

How to cite

Thomas Ardill, ‘Interior of St Giles’s Cathedral: Study for ‘George IV at St Giles’s, Edinburgh’ 1822 by Joseph Mallord William Turner’, catalogue entry, October 2008, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www