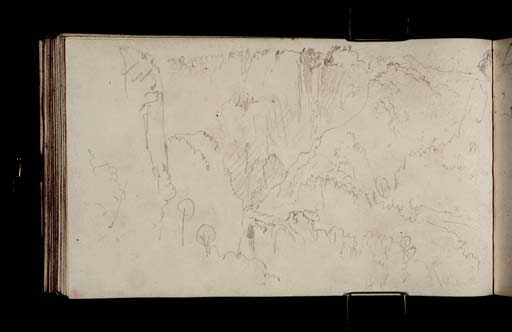

Joseph Mallord William Turner Cascata delle Marmore, from the Belvedere Inferiore 1819

Image 1 of 2

Joseph Mallord William Turner,

Cascata delle Marmore, from the Belvedere Inferiore

1819

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Folio 55 Verso:

Cascata delle Marmore, from the Belvedere Inferiore 1819

D14760

Turner Bequest CLXXVII 55 a

Turner Bequest CLXXVII 55 a

Pencil on white wove paper, 110 x 186 mm

Inscribed by the artist in pencil ‘Light’ above shaded area in centre of page and ‘[?W]’ centre of right-hand edge

Inscribed by the artist in pencil ‘Light’ above shaded area in centre of page and ‘[?W]’ centre of right-hand edge

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

References

1909

A.J. Finberg, A Complete Inventory of the Drawings of the Turner Bequest, London 1909, vol.I, p.522, as ‘Cascade of Terni’.

1966

Jack Lindsay, J.M.W. Turner: His Life and Work: A Critical Biography, London 1966, p.53.

1984

Cecilia Powell, ‘Turner on Classic Ground: His Visits to Central and Southern Italy and Related Paintings and Drawings’, unpublished Ph.D thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London 1984, pp. 101, 469 note 143, 103 note 150.

1987

Cecilia Powell, Turner in the South: Rome, Naples, Florence, New Haven and London 1987, p.34.

2008

James Hamilton, Nicola Moorby, Christopher Baker and others, Turner e l’Italia, exhibition catalogue, Palazzo dei Diamanti, Ferrara 2008, pp.44, 90 note 29.

2009

James Hamilton, Nicola Moorby, Christopher Baker and others, Turner & Italy, exhibition catalogue, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh 2009, pp.42, 150–1 note 29.

At the Umbrian town of Terni Turner made a short detour from the direct road to Rome in order to visit the famous waterfall, approximately three miles to the east. An entirely man-made phenomenon, the Falls of Terni were created by the ancient Romans who diverted the River Velino to descend into the Nera valley beneath in three successive stages. The whiteness of the waters led to the popular appellation of the ‘Cascata’ or ‘Caduta delle Marmore’ (Falls of Marble). During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the site represented one of the most popular tourist destinations in Italy outside of Rome and the Papal Government exercised a monopoly on guides and vehicle hire so that unless travellers were prepared to walk the distance from Terni, they were obliged to pay to access the site.1 In 1781, Pope Pius VI ordered the construction of two viewing huts to accommodate the increasing numbers of visitors. One of these shelters, the Belvedere Inferiore, allowed a vista of the entire spectacle from the bottom of the falls, whilst the other, the Belvedere Superiore, was situated on a projecting spur of rock, almost level with the brink of the summit. Both could be reached by the road from Terni which diverged at the small village of Papigno, see folios 49 verso–50 (D14749–50).

Like most tourists, Turner chose to visit both viewpoints. Sketches from the Belvedere Superiore can be found on folios 46, 46 verso, 48, 48 verso, 50 verso, 51–51 verso, 52 and 53 (D14742, D14743, D14746, D14747, D14751, D14752–3, D14754 and D14756). This sketch meanwhile, continued on the opposite sheet of the double-page spread, see folio 56 (D14761), depicts the view from below at the Belvedere Inferiore, with the three distinct stages of the falling cascades. The hut at the Belvedere Superiore, which still exists today, can be seen near the top right-hand corner of the page. Despite the swift schematic nature of the drawing, Turner has attempted to convey something of the power and force of the Falls within his sketch. He has used bold hatched lines and areas of shading to express the sheer weight of the water as it plunges from the top, and the mass of spray thrown up from the rocks. Further views from the Belvedere Inferiore can be found on folios 56 verso (D14762) and 57 (D14763).

Turner’s experience of the Cascata delle Marmore in 1819 was very much a confirmation of preconceived information rather than a pilgrimage of discovery. In fact, the only original painting he produced of the waterfall predates his first view of it. The finished watercolour, Cascade at Terni 1818 (Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery), belongs to the series of topographical illustrations for James Hakewill’s Picturesque Tour of Italy, published in 1819. 2 Like all of the designs related to the project, the composition of the view from the Belvedere Inferiore was based upon Hakewill’s own pencil sketches of the site, although the dramatic vertical format and delicate hazy colouring are entirely Turner’s own.3 By the early nineteenth century, the awe-inspiring spectacle of the plunging torrents had become a well-established spot for artists, writers and poets interested in observing the forces of nature. The Romantic poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822) for example, visited the falls in 1818, the year before Turner, and recounted the experience at length in a letter:

Imagine a river sixty feet in breadth, with a vast volume of waters, the outlet of a great lake among the higher mountains, falling 300 feet in a sightless gulph of snow white vapour which bursts up forever & forever from a circle of black crags, & thence leaping downwards make 5 or 6 other cataracts each 50 or 100 feet high which exhibit on a smaller scale & with beautiful & sublime variety the same appearances. But words, and far less could painting, will not express it. Stand upon the brink of the platform of cliff which is directly opposite. You see the evermoving water stream down. It comes in thick and tawny folds flaking off like solid snow gliding down a mountain. It does not seem hollow within, but without it is unequal like the folding of linen thrown carelessly down. Your eye follows it & it is lost below, not in the black rocks which gird it around but in its own foam & spray, in the cloudlike vapours boiling up from below, which is not like rain nor mist nor spray nor foam, but water in a shape wholly unlike any thing I ever saw before. It is as white as snow, but thick & impenetrable to the eye. The very imagination is bewildered in it. A thunder comes up from the abyss wonderful to hear: for though it ever sounds it is never the same, but modulated by the changing motion rises & falls intermittingly.4

Countless other descriptions appeared in literary and poetic form. In addition to accounts from contemporary travel guides, Turner in particular would have been familiar with Lord Byron’s immortalisation of the Falls in Canto IV of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (published 1818):

The roar of waters – from the headlong height!

Velino cleaves the wave-worn precipice;

The fall of waters! rapid as the light

The flashing mass foams shaking the abyss;

The hell of waters! where they howl and hiss,

And boil in endless torture; while the sweat

Of their great agony, wrung out from this

Their Phlegethon, curls round the rocks of jet

That gird the gulf around, in pitiless horror set.

Horribly beautiful! but on the verge,

From side to side, beneath the glittering morn,

An Iris sits, amidst the infernal surge,

Like Hope upon a death-bed, and, unworn

Its steady dyes, while all around is torn

By the distracted, bears serene

Its brilliant hues with all their beams unshorn:

Resembling, ‘mid the torture of the scene,

Love watching Madness with unalterable mien.

Velino cleaves the wave-worn precipice;

The fall of waters! rapid as the light

The flashing mass foams shaking the abyss;

The hell of waters! where they howl and hiss,

And boil in endless torture; while the sweat

Of their great agony, wrung out from this

Their Phlegethon, curls round the rocks of jet

That gird the gulf around, in pitiless horror set.

Horribly beautiful! but on the verge,

From side to side, beneath the glittering morn,

An Iris sits, amidst the infernal surge,

Like Hope upon a death-bed, and, unworn

Its steady dyes, while all around is torn

By the distracted, bears serene

Its brilliant hues with all their beams unshorn:

Resembling, ‘mid the torture of the scene,

Love watching Madness with unalterable mien.

(Byron, Childe Harold, Canto IV, stanzas 69–72)

He referred to the poem during his work on Hakewill’s Picturesque Tour of Italy, adding a rainbow across the centre of his watercolour of the falls. Some of Byron’s lines were even quoted in the text accompanying the illustration.5

In addition to textual accounts, Turner had come across a number of visual treatments of the subject prior to his 1819 visit. A Monro school watercolour by him after a view by John Robert Cozens (1752–1797) dates from circa 1794–7 (National Gallery of Ireland), and miniature pen-and-ink copies based upon prints after John ‘Warwick’ Smith (1749–1831) can be also be found in the Italian Guide Book sketchbook (see Tate D13964; Turner Bequest CLXXII 18). He is also likely to have seen a painting of the falls by Louis Ducros (1748–1810) in the collection of his patron, Sir Richard Colt Hoare at Stourhead. The latter shared Shelley’s belief that painting was an inadequate means of expressing the physicality of the Cascata since it was ‘one of those wonderful works of nature, which no mind can fancy, nor pencil delineate with appropriate grandeur’.6 Nevertheless, Colt Hoare praised Ducros’s depiction of the white spray thrown up by the churning waters, which employed pure watercolour without recourse to bodycolour.7 As an artist whose interests had long centred on the depiction of light and water Turner’s own finished watercolour of the Cascata reveals that he was undeterred by the challenge of capturing vaporous effects. However, despite the pleasure and excitement of having seen the waterfall at first hand, he seems to have gained no new inspiration or information from the visit and never used it as a subject again within his work.

Nicola Moorby

November 2008

Benjamin Colbert, Shelley’s Eye: Travel Writing and Aesthetic Vision, London 2005, pp.161–2. Today the site is still a popular visitor attraction. Most of the time however, the majority of the water is diverted for use in a hydroelectric power plant and the falls are only ‘turned on’ intermittently for the benefit of tourists, see http://www.marmore.it/document.php?id=14 , accessed November 2008.

Andrew Wilton, The Life and Work of J.M.W. Turner, Fribourg 1979, no.701; W[illiam] G[eorge] Rawlinson, The Engraved Work of J.M.W. Turner, R.A., vol.I, London 1908, no.145.

Tony Cubberley and Luke Herrmann, Twilight of the Grand Tour: A Catalogue of the drawings by James Hakewill in the British School at Rome Library, Rome 1992, no.2.53, p.170 reproduced.

Quoted in Benjamin Colbert, Shelley’s Eye: Travel Writing and Aesthetic Vision, London 2005, pp.162–3.

Richard Colt Hoare, Recollections Abroad, Bath 1818, vol.II, p.252, quoted in Pierre Chessex, Lindsay Stainton, Luc Boissanas et al, Images of the Grand Tour: Louis Ducros 1748–1810, exhibition catalogue, Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood 1985, p.[88].

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Cascata delle Marmore, from the Belvedere Inferiore 1819 by Joseph Mallord William Turner’, catalogue entry, November 2008, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www