Walter Richard Sickert Rowlandson House - Sunset 1910-11

Walter Richard Sickert,

Rowlandson House - Sunset

1910-11

Walter Sickert rented Rowlandson House in Camden Town from 1910–14, through the whole of his involvement with the Camden Town Group. This summertime view looks north up Hampstead Road from the back garden, the time of day nearing twilight, indicated by daubs of pink and mauve in the pale sky. The trees in the far background form the edge of Mornington Crescent Gardens. Sickert mostly painted interiors at the time, and this landscape may have been inspired by Spencer Gore, who made a number of pictures of the house and gardens when he stayed at Rowlandson House in the summer of 1911.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Rowlandson House – Sunset

1910–11

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 502 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ in black paint bottom left

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05088

Rowlandson House – Sunset

1910–11

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 502 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ in black paint bottom left

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05088

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist through Carfax & Co., London, by Lord Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, London, c.1912–14; by descent to his wife, Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, on his death 6 October 1931, by whom bequeathed to Tate Gallery 1940.

Exhibition history

1911

Forty-Sixth Exhibition of the New English Art Club, Royal Society of British Artists, London, November–December 1911 (30, as ‘Cruikshank’s House’).

1912

Esposizione internazionale d’arte della città di venezia, British Pavilion of the Venice Biennale, Venice, April–October 1912 (66, as ‘Casa di Cruikshanks’ [sic]).

1914

Twentieth-Century Art, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, May–June 1914 (434, as ‘Sunset – Rowlandson House’. Lent by Lord Henry Bentinck).

1916

Paintings by Walter Sickert, Carfax Gallery, London, November 1916 (7, as ‘Cruikshank’s House, lent by Lord Henry Bentinck, M.P.’).

1944

The Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions Second Exhibition, (Council for the Encouragement of Music and Arts tour), Manchester City Art Gallery, November–December 1944, City Museum and Art Gallery Birmingham, January–February 1945, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, March 1945, Central Museum and Art Gallery, Derby, April 1945, Wakefield Art Gallery, May–June 1945, Castle Museum, Norwich, July–August 1945, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, September–October 1945, Worthing Museum and Art Gallery, October–November 1945 (71, as ‘Rowlandson House, Bath’).

1945

The Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions Second Exhibition, National Gallery, London, June–July 1945 (68, as ‘Rowlandson House, Bath’).

1957

Chancellor of the Exchequer’s residence, 11 Downing Street, London 1957 (loan).

1965–76

Board of Trade, Admiralty House, London, c. October 1965–August 1976 (long loan).

1976

Camden Town Recalled, Fine Art Society, London, October–November 1976, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, November–December 1976 (143, as ‘The Garden of Rowlandson House – Sunset’).

1977–89

Government Art Collection, London, January 1977–January 1989 (long loan).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (9, reproduced).

References

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, p.101.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.629.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London 1973, pp.117, 352 no.290, reproduced pl.200, as Garden of Rowlandson House.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, pp.27, 190, 194, 373, 390, reproduced pl.61.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.205.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.324, pp.79, 354.

Technique and condition

Walter Sickert painted on a pre-primed canvas purchased from the London colourman P. Shea, who had premises close to Sickert’s studio on Fitzroy Street. The linen canvas has a very fine open weave typical of French or Belgian manufacture. It was primed with a thin layer of chalk and zinc white bound in a tempera medium providing an absorbent ground for oil painting.1 Such priming reflects the earlier influence of James Abbott McNeill Whistler, who is known to have worked on an absorbent grey priming.2 However, this priming is white and is just visible in a few areas where the paint is thinner at the edges, bottom and in the mid-ground, confirming that no coloured second priming or toning layer was applied to the ground, as in previous works. Sickert selected this particular type of priming because it facilitated a more direct painting technique in keeping with the impressionist style of the work (see Tate N05092). The original design is drawn in grey paint or crayon and is also almost entirely covered by later paint. The artist has applied what appears to be thinned oil paint but brushed strongly to create impasto areas. The impasted areas are richer in medium suggesting that the leanness comes in part from the absorbent ground, which has drawn oil from overlying paint layers. However, some of the darker colours are also lean and underbound at the surface, suggesting that the artist may also have extracted medium using blotting paper prior to painting.

The painting method is immediate but the extensive covering suggests a more laboured application. Most of the visible top layers were applied in one operation but there are at least two painting regimes with drying time between layers. In some areas there is a dense build-up of different coloured layers, recalling that seen in the work of Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore; the mass of the building to the left, for example, is in olive green over purple and a thin red layer. The paint is applied not up to the drawing but more freely across it in a more impressionist technique, sometimes deliberately breaking up the architectural details or leaving incomplete detail to be filled in by the eye, such as in the building in the centre or the garden in the foreground composed of relatively unstructured dabs of different greens. The sky is much lighter in tone and applied with deliberately strong blue brushed lines and dabbed white clouds to give it movement and texture. The colours are generally opaque and devoid of glazing, the surface is unvarnished and there is no obvious discolouration of paint, so that the painting has retained a cool tonality and matt aesthetic.

Stephen Hackney

November 2005

Notes

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', November 2005, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Rowlandson House – Sunset 1910–11 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, January 2004, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

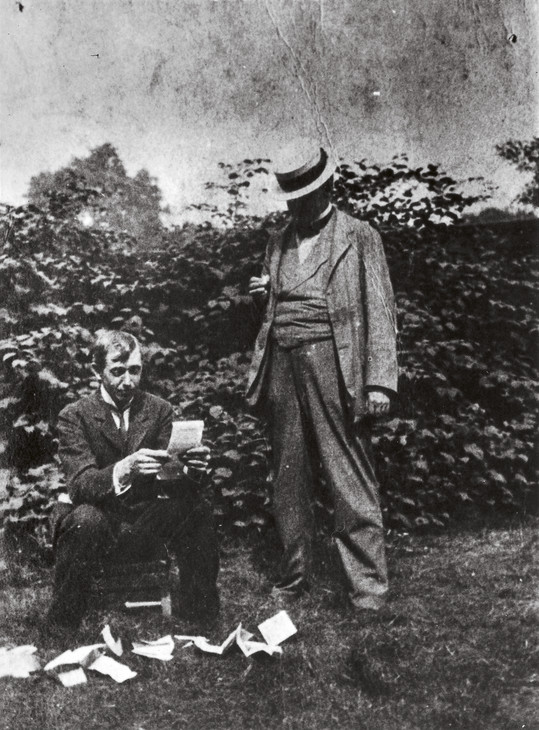

Spencer Gore and Walter Sickert reading press cuttings of the first Camden Town Group exhibition in the garden of Rowlandson House June 1911

Courtesy of Wendy Baron

Fig.1

Spencer Gore and Walter Sickert reading press cuttings of the first Camden Town Group exhibition in the garden of Rowlandson House June 1911

Courtesy of Wendy Baron

Rowlandson House was at the southern end of a short terrace of three Victorian houses that stood on Hampstead Road, in a small area of land between the street and the railway tracks leading north out of Euston. One of Sickert’s pupils, the writer Enid Bagnold (1889–1981), described it as ‘one of those odd broken houses that seemed to have had another house torn from its side, overhanging a railway (was it built on a bridge?)’.2 The area was completely transformed during the late 1960s by the creation of the Ampthill Estate and there is now no remaining trace of the building. An Ordnance Survey map from 1958 reveals that the house was still in existence at this date and that it was a substantial property with steps descending from an entrance at the right to a large garden stretching round behind the house. Rowlandson House – Sunset was painted from the lawn of the garden at the back of the house facing north up Hampstead Road. The art historian Wendy Baron has identified the view as ‘looking over the wall of his garden, past the backs of the next two, much narrower, houses to glimpse the rather grand united façade of the terrace built from No.247 Hampstead Road (Wellington House Academy where he had a studio) to the opening of Mornington Crescent’.3 Broken touches of pink and mauve paint in the sky intensify on the left, indicating the presence of the setting sun in the west. A number of paintbrush hairs caught in the paint reveal the vigour and force with which Sickert applied the pigment to the canvas.4 In the foreground of the painting at the left, a distinctive brick arch curves up from the leafy shrubs adjoining the wall. It is not clear what this construction might be but it looks like the remains of a partly destroyed outhouse, or perhaps a decorative feature across which flowers could be trained to grow.

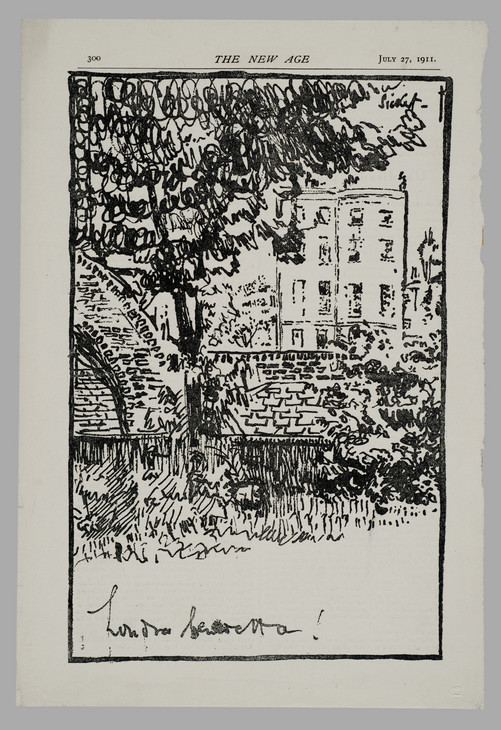

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Londra Benedetta! 1911

Lithograph on paper

335 x 227 mm

Inscribed by the artist 'Londra benedetta!' bottom left

Tate Archive TGA 8120/3/50

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

Londra Benedetta! 1911

Tate Archive TGA 8120/3/50

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Title and date

There has been some confusion in the past over the title and dating of Rowlandson House – Sunset. A label removed from the back of the stretcher indicates that the painting was displayed at the Venice Biennale in 1912,6 where it must have been exhibited as Casa di Cruikshanks [sic] (Cruikshank’s House). This alternative title refers to the house occupied by the caricaturist and illustrator of Dickens, George Cruikshank (1792–1878), from 1850 until his death in 1878. The house, at 48 Mornington Place, was renumbered in 1864 as 263 Hampstead Road and stood at the entrance to Mornington Crescent.7 It should not be confused with a second Camden Town address, 31 Augustus Street, where Cruikshank appears to have secretly maintained his mistress, Adelaide Attree.8 From around 1909 Sickert rented 31 Augustus Street as a studio and referred to it as ‘Cruikshank’s House’. In Sickert’s painting, 263 Hampstead Road is part of the block of houses standing in the middle distance. The trees visible to the right of the terrace represent the edge of Mornington Crescent Gardens which were replaced in 1926 by the Carreras cigarette factory. The same terrace appears in an etching by Sickert, Cruikshank’s House on Coronation Day 1911 (Lessore Collection).9 Handwritten inscriptions by Sickert on one impression of this print confirm that Cruikshank’s House stood very close to Wellington House Academy, another of Sickert’s addresses at 247 Hampstead Road which he rented from 1908–c.1914. The etching was probably based upon a painting in watercolour and pencil described by Wendy Baron as a view of Rowlandson House decorated with flags to celebrate the coronation of George V in June 1911.10

In the early 1960s an Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery, Dennis Farr, noted that a painting entitled Cruikshank’s House was exhibited at the Carfax Gallery in May 1912 and also at the Carfax in November 1916.11 Between April–October 1912 Rowlandson House – Sunset was being shown at the Venice Biennale under the title Cruikshank’s House and therefore cannot also have been included in the exhibition at the Carfax Gallery in May. This shows the existence of two completely separate paintings sharing the same title. Fortunately, the visual appearance of the version of Cruikshank’s House exhibited at the Carfax show in May 1912 is recorded in a small contemporary pencil sketch by an unknown hand in the back of an annotated copy of the catalogue in the Tate Library.12 Although the drawing is very small and slight, it nonetheless provides enough detail to identify the work as identical to one sold at Christie’s in 1974 with the title, Hampstead.13 This painting replicates the view towards Mornington Crescent in Rowlandson House – Sunset but adopts a viewpoint closer to the garden wall that excludes the tall adjacent houses visible in Tate’s version.

At the later Carfax exhibition in 1916, the painting entitled Cruikshank’s House is described in the catalogue as being lent by Lord Henry Bentinck, M.P., confirming that this version is in fact the painting now in Tate’s collection. The painting was described by Sir Claude Phillips in the Daily Telegraph as a

beautiful town landscape, Cruikshank’s House, an evening piece, in which, above house and garden already cool in transparent shadow, there scintillates a sky bright still with points of reddening golden light. Here a note of wistfulness, of poetry, indefinable yet unmistakeable, makes itself, heard, and adds a higher beauty to the quiet scene, without altering its character.14

A painting entitled Cruikshank’s House had also been exhibited at the New English Art Club in 1911 and an anonymous pencil annotation in the catalogue of the 1916 Carfax show in the Tate Library suggests that they are the same painting.15 Rowlandson House – Sunset has previously been catalogued with a date of 1910–12. However, this new evidence regarding the exhibition history of the painting, combined with the subject matter and style of the painting, suggests 1911 as the most probable date of execution, although the possibility remains that it could have been painted the year before when Sickert first occupied the house.

Urban landscape

The urban landscape of London was not a usual subject for Sickert, although he had earlier made a specialty of depicting Dieppe. His interests famously lay with painting figures in dingy and dilapidated north London interiors and the characters observed from the audience of the music hall. However, between 1910 and 1914 Sickert portrayed a number of views from his various properties on or near Hampstead Road, for example Hampstead (Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museum).16 The critics relished Sickert’s move away from the grim Camden Town interiors. His uncharacteristic deviation from indoors to outdoors reflects his close association with certain members of the Camden Town Group, in particular Harold Gilman, Charles Ginner and most importantly, Spencer Gore, who regularly painted images of the city’s back streets and houses.

On 29 July 1911 Sickert got married for a second time, to Christine Angus, one of his students from Rowlandson House, and they spent the rest of the summer in Neuville, a suburb of Dieppe in northern France. He was always very generous about offering his friends and colleagues the use of his various properties, and during his absence he presented Gore with the run of Rowlandson House. At that time the younger artist was lodging with the local vicar in nearby Mornington Crescent. Since he was also courting his future wife, Mollie, he no doubt was grateful for the opportunity for privacy and space and made full use of Sickert’s offer. Gore consequently produced a series of paintings featuring Sickert’s house and garden. Painted in the brilliant colours of Gore’s characteristically bright palette these works include The White Seats, Rowlandson House 1911 (Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria), From the Garden of Rowlandson House 1911 (Toledo Museum of Arts, Ohio),17 The Garden, Rowlandson House 1911 (private collection),18 The Artist’s Wife in the Garden of Rowlandson House c.1911 (private collection),19 and The Nursery Window, Rowlandson House 1911 (private collection).20 Another painting, The Garden of Rowlandson House c.1911 (University of Hull Art Collection), replicates the view as depicted by Sickert in Rowlandson House – Sunset, looking over the garden wall towards Mornington Crescent Gardens. It is not known whether Sickert only first considered painting the view from his garden after seeing Gore’s work from the summer of 1911, or whether Gore was inspired to make a version of a picture Sickert had already completed. Gore’s painting occupies a viewpoint nearer to the wall and reveals a typical Camden Town interest in the colours and patterns of the buildings. By comparison, Sickert seems less concerned with the topographical view and more involved with depicting the foliage of the garden and the appearance of the sky.

Rowlandson House

Rowlandson House was significant, not only as the location of Sickert’s school of drawing, etching and painting, but also because it represented one of the busiest and most influential periods of his career. Sickert’s occupancy of the house, from 1910 to 1914, encompassed the entire lifespan of his involvement with the Camden Town Group, from its inception and roots in Fitzroy Street, through its active exhibiting period to its eventual evolution into the London Group. Yet, despite time devoted to the organisation of the group and its exhibitions, Sickert did not neglect his own painting and artistic development. According to his biographer, Robert Emmons, it was at Rowlandson House that Sickert painted his portrait of Jacques-Emile Blanche c.1910 (Tate N04912).

In her catalogue raisonné of Sickert’s prints, Ruth Bromberg has discussed how the printmaking facilities provided for the students on the top floor also encouraged Sickert’s own production of etchings to flourish at this time.21 Between 1910–14, Sickert printed and editioned for sale three etchings: Noctes Ambrosianae; The Old Bedford, The Small Plate; and Dieppe, The Old Hotel Royal.22 He also produced a number of other images, many of which bear a studio stamp in violet ink, ‘Cumberland Market Press’, referring to the old hay market a short distance from the school.23 During this period, Sickert also contributed regular art criticism to the New Age and the Art News, taught four nights a week at the Westminster School of Art and was a familiar figure amidst the social dinners and gatherings of London’s cultural elite. In his biography of the artist, Robert Emmons describes the fifty-year-old Sickert’s hectic schedule at this time, recording that he ‘taught every morning: slept in the afternoon at one of his rooms, with a handkerchief tied round his head to keep his jaw up: worked by himself from models after tea: and taught again at the Westminster in the evenings’.24

The teaching of art emerged as an interest early in Sickert’s career and remained an important preoccupation throughout his life (he was still teaching as late as 1938 when, aged seventy-eight, he gave classes on drawing at a boys’ preparatory school near his home in Broadstairs, Kent).25 Prior to starting the school at Rowlandson House, Sickert had taught at the Westminster School of Art, at a private studio in Paris and at an art school in London run by his friend, Florence Pash. In the autumn of 1909, Sickert instituted private etching classes in his studio at 31 Augustus Street. These classes seem to have been attended by only two students whom Sickert had first taught at the Westminster School of Art, Madeline Knox (1890–1975) and Ambrose McEvoy (1878–1927). This modest beginning seems to have inspired Sickert to undertake a teaching project on a more ambitious scale and later that year he opened a school of etching at 209 Hampstead Road. In early 1910, the larger premises of 140 Hampstead Road became vacant and he decided to move the school across the road and to expand its remit to include drawing and painting. Sickert intended the school to provide him with a regular income aside from the unreliable sale of pictures, but he also relished the role of teacher. Sickert ran Rowlandson House in partnership with the young Madeline Knox, who in 1919 was to marry Arthur Clifton of the Carfax Gallery. Her role was both to assist Sickert in the running of the school and to provide financial backing for the enterprise. Unsurprisingly, the time and energy required for Sickert’s numerous commitments proved to be a strain on his health and in early 1910 he became unwell, leaving the teaching and administrative running of the school in the hands of Knox. She was only about twenty years of age at this time, and the impression from a portrait of her by Gilman from c.1910–11 (Tate T13024) is that she was too young and inexperienced to be landed with so much responsibility. She in turn became ill and stopped working at the school. Sickert was forced to reconsider the enterprise and wrote to his friends Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson:

By the mercy of providence the new McColl society [Contemporary Art Society] (which I have done nothing but abuse) have heaped coals of fire on my head & bought George Moore’s portrait.26 I do not yet know for how much. In any case that will enable me to give Miss Knox her money out in one or two payments. I am grieved at her breakdown & of course reproach myself with allowing her to do so much. But she had the deceptive pluck of the spirited young, who look upon a suggestion that anything is too much for their strength as almost a rejection. The thing however having happened, it will be a relief to me henceforth to be risking no one else’s money. I couldn’t foresee my illness or of course I should not have dreamt of the partnership.27

Although Knox abandoned teaching at Rowlandson House she persisted with her own artistic development and in 1916 she held a solo exhibition at the Carfax Gallery. In later life she specialised in exquisitely worked needlework after her own designs.28

Knox’s absence at Rowlandson House was filled by another of Sickert’s pupils, Sylvia Gosse (1881–1968),29 who took over the management of the school and a share of the teaching. She did not contribute any money but Sickert offered her half of the profits, probably in lieu of a formal salary. She in turn tried to curb his excessive spending on equipment for the school such as special easels and an expensive stove for the heating.30 Sickert and Gosse continued to run Rowlandson House until June 1914 when Sickert decided that the time and energy devoted to it was having an adverse effect on his own painting and the decision was taken to close the school and vacate the premises.

Classes at Rowlandson House were held during weekdays, 10 am to 4 pm,31 and were largely comprised of women, although McEvoy and Malcolm Drummond also attended, and Gilman was an occasional visitor. There was also a class for children taught in the afternoons,32 and an evening model from 5 to 7 pm, Monday to Thursday.33 Students could attend two or five days a week and the fees were charged accordingly: four guineas a term or 11 guineas a year for two days a week; 10 guineas a term or 27 guineas a year for five days.34 Gosse’s friend Kathleen Fisher records that the school took in students with a wide variety of abilities and experience, some of whom demonstrated little talent and probably enrolled for social reasons.35 Sickert seems to have viewed these pupils with a mixture of affection and impatient superiority, writing to Hudson in 1913: ‘The school is booming. I have already broken in the wills of two rather sad, but hopeful & quite sympathetic, new spinsters.’36 The classes were eventually arranged so that Gosse took the beginners and less able students, while Sickert taught the more advanced and talented artists.37

Sylvia Gosse 1881–1968

The Garden, Rowlandson House, with Students at Sickert's School 1912

Pen and black ink with grey wash and pencil on paper

315 x 359 mm

British Museum, London

© Estate of Sylvia Gosse / Bridgeman Art Library

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.3

Sylvia Gosse

The Garden, Rowlandson House, with Students at Sickert's School 1912

British Museum, London

© Estate of Sylvia Gosse / Bridgeman Art Library

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Despite a tendency to produce pupils indoctrinated in his style, there are many accounts to testify that Sickert was a very good instructor. He was an erudite and charismatic personality who charmed his students with his wit. Enid Bagnold studied with Sickert at Rowlandson House and described him as ‘such a teacher as would make a kitchenmaid exhibit once’. She recorded that ‘We were all enslaved, enchanted. The day glittered because of him ... His lightning-teaching tore across clouds of muddle and broke them up. For a time.’40 Another pupil, Elfrida Lucas, recalled Sickert’s

wonderful kindness to fellow-artists and young art students. ‘He was always encouraging me,’ she said, ‘and lent me his own palette and brushes. He took infinite pains to teach me to paint some wonderful flowers while he was at work on a portrait of himself ... He was a wonderful teacher. I heard him lecture to a roomful of students and budding artists, and shall never forget it or him.’41

In July 1913 an exhibition was held at the Carfax Gallery of paintings, drawings and etchings by past and present pupils of Sickert, many of whom must have been enrolled at Rowlandson House. The majority of exhibited works seems to have been still lifes, domestic interiors and London landscapes. The list includes a painting on sale for five guineas entitled The Garden, Rowlandson House by S. Gunston.42

Ownership

The first owner of Rowlandson House – Sunset was Lord Henry Cavendish-Bentinck (1863–1931), a Conservative MP and soldier who served in the Boer War and in the Dardanelles during the First World War. The Cavendish-Bentinck family was a large and aristocratic dynasty, descending from the Duke of Portland, and with a distinguished history in British public life. Lord Henry Bentinck was half-brother to the sixth Duke of Portland and lived in London at Grosvenor Place.

He accumulated a significant collection of contemporary British art in which he was often advised and encouraged by his younger sister, the renowned society hostess, Lady Ottoline Morrell (1873–1938).43 It is not known exactly when he bought Rowlandson House but to judge from the exhibition history it was between 1912 and 1914, prior to lending it to the Whitechapel Art Gallery in May of that year. Part of his collection was bequeathed to the Tate in 1940 on the death of his widow, Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck (née Olivia Caroline Amelia Taylour, 1869–1939). The bequest included eleven other works by Sickert, two paintings by Gore and five drawings and paintings by Augustus John. The rest of the collection was sold at Christie’s in April 1940.44 This included four paintings and two drawings by Sickert and works by Walter Bayes, Robert Bevan, Gore, Duncan Grant, J.D. Innes and Henry Lamb. As a patron, Lord Bentinck is interesting because an enthusiasm for Camden Town paintings was unusual among the upper classes.

Nicola Moorby

January 2004

Notes

Walter Sickert, ‘Du Maurier’s Drawings’, Speaker, 27 March 1897, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford and New York 2000, p.152.

Nancy Wade, ‘The Painting Technique of Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942’, unpublished Diploma Research Project, Courtauld Institute of Art, Department of Conservation and Technology 2001, p.18.

Reproduced in Ruth Bromberg, Walter Sickert Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven and London 2000, no.140.

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.629.

Paintings and Drawings by Walter Sickert, exhibition catalogue, Carfax Gallery, London 1912 (53), annotated copy, Tate Library, reproduced in Anna Gruetzner Robins, Walter Sickert: Drawings, Aldershot and Vermont 1996, p.93.

Christie’s, London, 1 March 1974 (lot 116), reproduced in Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.324.1.

Paintings by Walter Sickert, exhibition catalogue, Carfax Gallery, London 1916 (7), annotated copy, Tate Library.

Reproduced in An Ordinary Life: Camden Town Painters, exhibition catalogue, Aberdeen Art Gallery 1999 (36) and Baron 2006, no.324.2.

Reproduced in Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1974 (14).

Reproduced in Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, no.55.

Wendy Baron and Richard Shone (eds.), Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, p.53.

Walter Sickert, letter to Nan Hudson and Ethel Sands, [December 1910], Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.75.

Wendy Baron, Miss Ethel Sands and her Circle, London 1977, p.87 n.18. Knox’s handiwork can be seen in the altar frontal in Stanley Spencer’s Sandham Memorial Chapel at Burghclere in Hampshire (c.1935–6). For more on Knox, see Tate T13024.

‘Sickert & Gosse School of Drawing and Painting’, pamphlet, Islington Local History Collection, 11.1.

Walter Sickert, letter to Nan Hudson and Ethel Sands, [December 1910], Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.75.

‘Sickert & Gosse School of Drawing and Painting’, pamphlet, Islington Local History Collection, 11.1.

Paintings, Drawings and Etchings by Past and Present Pupils of Mr. Sickert, exhibition catalogue, Carfax Gallery, London 1913 (34).

Related biographies

Related essays

- A History of Camden Town 1895–1914 David Hayes

Related archive items

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Rowlandson House – Sunset 1910–11 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, January 2004, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www