Albert Rutherston Paddling 1911

Albert Rutherston,

Paddling

1911

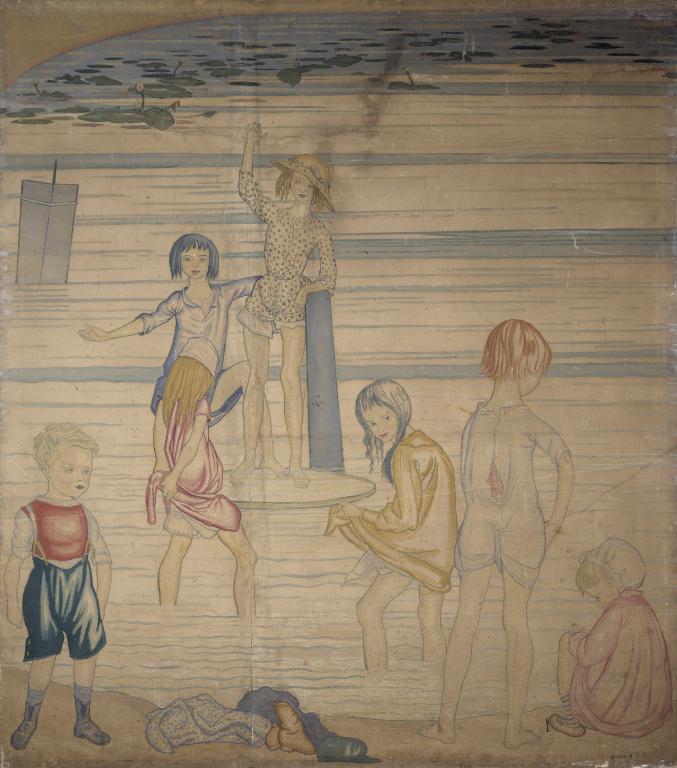

This painting shows a group of seven children wading in the waters of the Serpentine in Hyde Park. It was one of seven designs completed for the decoration of the Borough Polytechnic dining room in south London, a commission organised by Roger Fry. Rutherston’s contribution marked a turning point in his style and subject matter away from working-class realism towards illustrative landscapes populated by idealised children.

Albert Rutherston 1881–1953

Paddling

1911

Tempera on canvas

2277 x 2013 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Albert R.’ in blue paint bottom right

Purchased (Clarke Fund) 1931

N04569

1911

Tempera on canvas

2277 x 2013 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Albert R.’ in blue paint bottom right

Purchased (Clarke Fund) 1931

N04569

Ownership history

Painted for the Borough Polytechnic, London, from whom bought 1931.

Exhibition history

1911–29

On display as a mural, Borough Polytechnic, London 1911–29.

References

1912

Sketch, Supplement, 6 March 1912, pp.6–7.

1925

R.M.Y. Gleadowe, Albert Rutherston, London 1925, pp.19–20, reproduced pl.8, as Paddling in the Serpentine.

1940

Virginia Woolf, Roger Fry: A Biography, London 1940, p.173.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.581.

1980

Frances Spalding, Roger Fry: Art and Life, London and New York 1980, p.149.

1981

Isabelle Anscombe, Omega and After: Bloomsbury and the Decorative Arts, London 1981, p.13.

1985

Richard Cork, Art Beyond the Gallery in Early Twentieth Century England, New Haven and London 1985, p.120, as Paddlers.

1988

Max Rutherston, Albert Rutherston, London 1988, p.9.

1993

Richard Shone, Bloomsbury Portraits, London 1993, pp.63–4.

1996

Albert Rutherston, exhibition catalogue, Sally Hunter Fine Art, London 1996, [p.2].

1997

Anna Gruetzner Robins, Modern Art in Britain 1910–1914, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1997, fig.27.

1999

Christopher Green (ed.), Art Made Modern: Roger Fry’s Vision of Art, exhibition catalogue, Courtauld Institute Gallery, London 1999, pp.63, 79.

1999

Stephen Hackney, Rica Jones and Joyce Townsend (eds.), Paint and Purpose: A Study of Technique in British Art, London 1999, p.205.

1999

Richard Shone, The Art of Bloomsbury, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1999, p.148.

2000

Clare A.P. Willsdon, Mural Painting in Britain 1840–1940: Image and Meaning, Oxford and New York 2000, p.283.

2004

Christopher Reed, Bloomsbury Rooms: Modernism, Subculture, and Domesticity, New Haven and London 2004, p.72.

Technique and condition

Paddling is painted on a coarse plain-weave linen canvas consisting of two pieces of cloth that have been joined along the vertical length, left of centre. The two pieces were joined together to form the large format canvas prior to painting and the join is supported by a wide heavy strip of fabric glued to the reverse. Some time during the painting’s history the two pieces of cloth appear to have been parted and re-joined perhaps as the join failed.

The canvas is attached to a seven-member softwood stretcher, but creases running vertically and horizontally across the surface suggest that the painting was once removed from its stretcher and rolled and/or folded, probably for storage and/or transportation. The canvas was prepared with a thin layer of size, which was not sufficient to prevent the primer from passing through the weave interstices to the back. White primer in a tempera medium was applied onto the sized canvas in broad multi-directional strokes that remain visible at the surface. A warm brown toning layer was applied over the white primer providing an optical ground.

There is no visible evidence of initial drawing, perhaps reflecting how quickly the design was conceived. The contours of the figures are marked out in blue/green paint applied directly onto the optical ground using the tip of a fine brush. According to documentary sources the artist used a mixture or oil, wax and turpentine as his medium. Colour was applied within the contours of the figures, using pure hues with little mixing. Form was built up through the application of three shades of each colour, ranging from dark to light, working in from the edges of shapes and folds. The degree of finish varies across the surface. The red vest and blue shorts of the young boy are composed of a solid build-up of opaque colour, his boots modulated with opaque tones of dark blue overlaid with pink highlights. In contrast, the dress of the squatting girl in the lower right-hand corner is coloured with lean tonal washes of pink that reveal the underpaint. The subtle tones of the flesh are created using a slightly warmer tone of the buff-coloured underpaint. Touches of impasto and heightened colour are applied in the later stages of painting providing highlights and accents of colour, for example, in strands of hair, in the lips and in the eyes. The rebate edges are painted on all sides with a pattern of pink and orange rectangular staggered blocks, which would be visible when the painting was left unframed and hung directly onto the wall so as to appear like a mural.

Natasha Walker

November 2005

How to cite

Natasha Walker, 'Technique and Condition', November 2005, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Paddling 1911 by Albert Rutherston’, catalogue entry, October 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

The Fitzroy Street and Camden Town Group painters were not the only artists with whom Albert Rutherston was associated. Through friendships consolidated at the Slade School of Fine Art, the New English Art Club and through his elder brother, William Rothenstein, Rutherston was acquainted with many of the most progressive, talented and exciting artists of the time. Although he avoided becoming too closely affiliated with any one particular movement or circle, his network of connections ensured that he was nevertheless offered opportunities to participate in various group undertakings. One such project was Roger Fry’s scheme of decorative murals for the Borough Polytechnic (now called London South Bank University) in Elephant and Castle, south London. Paddling is one of seven large panels painted by a group of six artists for the students’ dining room in 1911.

The Borough Polytechnic was founded in 1892 as one of a network of institutions established in London at the end of the nineteenth century. Its stated aims were ‘the promotion of the industrial skill, general knowledge, health and well being of young men and women belonging to the poorer classes’.1 The polytechnic specialised in vocational, technical and craft classes such as mechanical engineering, wood-carving, shoe manufacture, laundry, needlework, bakery and hygiene. The main Borough Road building, which still stands today, was originally built in 1817 as the home of the British and Foreign School Society. The original motto of the institution, ‘Do it with thy might’, is still carved in stone over the entrance. During the academic year 1911–12, there were just over five thousand students enrolled.2

The mural commission was the idea of the Chairman of the House Committee, Basil Williams, who wanted to demonstrate that public areas such as refectories and halls could be rendered attractive at a relatively small cost through painted decoration.3 Williams approached his old friend from King’s College, Cambridge, Roger Fry (1866–1934), and asked him to oversee a scheme to decorate the walls, passage way and stairs leading to ‘Room No.9, which was used as a dining room for the Boys’ and Girls’ Schools and in the evening as a Club Meeting room’.4 Fry, who was keen both to promote the integration of modern art in everyday life and to support contemporary artists, organised three young painters, Bernard Adeney (1878–1966), Frederick Etchells (1886–1973) and Duncan Grant (1885–1978), to assist him with the decorations. Work was initiated during the summer vacation on 1 August 1911 and at some point it was decided that extra help was needed to hasten completion of the project and two further artists were drafted in, Macdonald (Max) Gill (1884–1947), brother of the sculptor Eric Gill, and Albert Rutherston. The choice of collaborators seems to have been based on the grounds of friendship and availability rather than any sense of shared artistic sensibilities.

The format and materials used for the murals were dictated by the circumstances of the commission. The walls of the passageway and stairs were adorned with blocks of abstract colour (blue, orange, white and yellow) but the dining room itself was decorated with a selection of mural panels showing scenes of leisure activities and holiday pleasures.5 The decision was made to paint on canvas rather than directly on to the wall so that the images could be moved in the event of structural changes to the building.6 The panels were created by joining strips of canvas together in four widths of six feet, two widths of ten feet and one long length of twenty feet for the entire end wall (painted by Etchells). The height of the murals was seven feet and the decorations were hung high up enough on the walls to avoid everyday damage caused by people eating in the room. Owing to the large scale of the panels and the desire to produce a cohesive, harmonious decorative scheme, the canvases were painted on site and, according to Duncan Grant, took between a week and ten days to complete.7 The necessity to keep the costs of the project to a minimum influenced the medium employed, which was an experimental mixture of oil, turpentine and wax, rather than more expensive tempera paint. This has subsequently proved to be an unstable substance and has caused problems in the long-term conservation of the murals. The House Committee paid Fry a fee of £100 to be divided among the artists and they also gave £55 8 shillings for expenses.

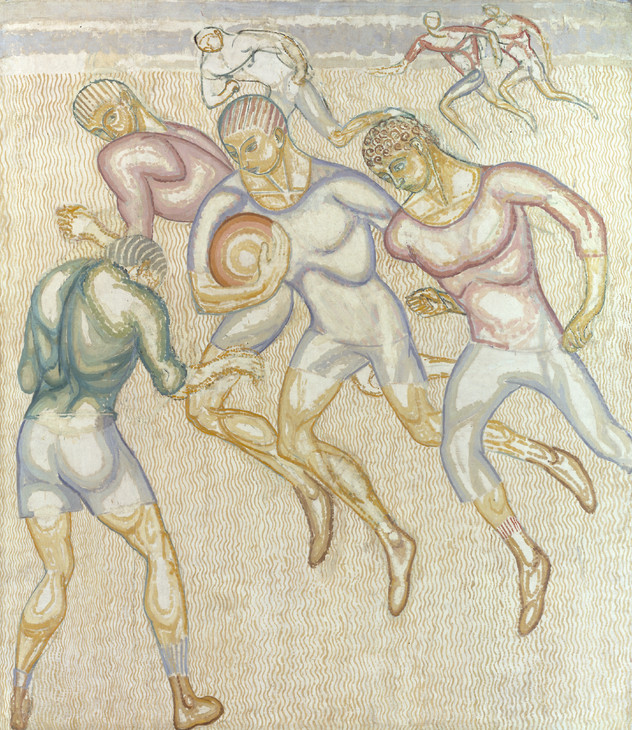

Duncan Grant 1885–1978

Football 1911

Oil on canvas

support: 2277 x 1975 x 25 mm

Tate N04566

Purchased 1931

© Tate

Fig.1

Duncan Grant

Football 1911

Tate N04566

© Tate

Duncan Grant 1885–1978

Bathing 1911

Oil on canvas

support: 2286 x 3061 mm

Tate N04567

Purchased 1931

© Tate

Fig.2

Duncan Grant

Bathing 1911

Tate N04567

© Tate

Macdonald Gill 1884–1947

Punch and Judy 1911

Tempera on canvas

support: 2286 x 1861 mm

Tate N04570

Purchased 1931

Fig.3

Macdonald Gill

Punch and Judy 1911

Tate N04570

The scheme was applauded by the art critic of the Athenæum (probably Camden Town Group member Walter Bayes) for its choice of modern themes:

Of late years public monuments and public decorations have become little better than public laughing stocks. Our walls are smothered with classical and mythological figures painted in that empty rhetorical style bequeathed by the Late Renaissance. A bad tradition is supreme; and the decorators of the Borough Polytechnic must prepare to be howled at as anarchists and charlatans because, instead of setting themselves to copy the works of dead masters, they have dared to attempt what the masters achieved – the expression that is of the significance of contemporary life.10

Although the modern subject matter and the use of a bright post-impressionist palette led to the murals being hailed as examples of the new developments in British art, the scheme also reflected Roger Fry’s high regard for early Italian art and for the Byzantine mosaics he had seen on a recent trip to Turkey in April 1911 with Vanessa and Clive Bell.11 Fry’s attempts to impose some unity of design between the seven panels were rather relaxed, but there was an informal agreement between the artists to employ a limited range of colours and flat, stylised forms and, as Bernard Adeney explained, ‘to employ the technique of graduating the colour tones to a dark contour to increase the rhythm of the design – as in Byzantine mosaics’.12 In addition, each scene was surrounded by the same diaper design border, possibly inspired by the patterned bands of the mosaics at Ravenna or the frescos of Giotto.13 Despite these measures, however, there are notable stylistic differences between the work of the six artists and the finished paintings did not achieve a satisfactory and unified whole. The least successful and most obviously different of all the designs is Paddling, the contribution of Rutherston, which has been described as one of his ‘less felicitous efforts’.14

Subject and style

Rutherston’s panel shows a group of seven boys and girls paddling their feet in the waters of the Serpentine in Hyde Park. Three children stand or sit on the bank at the edge of the water in the foreground of the painting. Beyond them, two girls hold up their dresses while getting their feet wet in the shallows and in the centre of the panel two more children stand waving on a small round wooden platform. In the background can be seen the leaves and flowers of water-lilies with the lake curving away at the top left-hand corner. The style of the panel marks a transitional stage for Rutherston. During 1910 his art underwent a significant shift in outlook and he abandoned the detailed realism he had previously favoured and began instead to experiment with an illustrative, linear style using the unusual medium of watercolour on silk. His paintings no longer featured working-class characters in dingy interiors, but were fictionalised Mediterranean-style landscapes populated by idealised children, for example, The Adventure 1910 (private collection).15 Rutherston later cited the inspiration behind this dramatic change as his experience of the light and colour of the south of France which he visited in 1910 with the artist Gerald Chowne and his wife. He told Stanley Casson:

I once found myself in a certain part of the world where there were so many things that excited me and attracted me, stimulating the wish to do so much with them, that I fancy I began unconsciously to invent for myself a method of attack towards this end. My older and more solemn method of painting would not have proved elastic enough.16

Max Rutherston, the artist’s grandson, has also speculated that the impetus for the change may have originated in his grandfather’s desire to move into a professional artistic field different from that of his older brother, William.17

The visual appearance of Paddling reveals the emergence of Rutherston’s new interests, particularly in the depiction of children, described by R.M.Y. Gleadowe as ‘spritely, elfin but yet “gamin” types’.18 The children combine a mixture of sentimental innocence and slightly knowing and provocative appeal which is unsettling to the modern viewer but was an accepted form of representation during the period. However, Rutherston’s attempt to render the childish, ungainly poses of the figures does not translate well to the large scale of the Borough mural panels and his style is inconsistent across the image.

Rutherston’s inclusion in the Borough Polytechnic project was an unexpected and last minute opportunity, and the design for Paddling had to be produced very quickly. It is probable therefore that the figures of the children were based upon sketches already made by Rutherston of his nephews and nieces on holiday. He was very fond of his brother William’s offspring, John (born 1901), Rachel (born 1903), Betty (born 1905) and William Michael (born 1908), and he often spent time with them and their mother, Grace. They appear in a number of drawings and paintings around 1910, for example The Rothenstein Children (John, Rachel, Betty, Billy) at Vaucottes-sur-mer 1910 (private collection)19 which shows the children paddling in a rock pool by the seaside. John and his two sisters were also the models for a watercolour on silk design, The Smart Visitor (private collection),20 exhibited at the New English Art Club in May 1911,21 and there are similarities in the poses of the two girls in this to a couple of the children in Paddling. In particular, the dark-haired girl looking at the viewer over her shoulder and holding her dress up out of the water is reminiscent of the girl holding the flowers in The Smart Visitor.

Rutherston seems to have made little attempt to mirror the more angular, stylised forms favoured by Fry, Grant and the others. As the art historian Frances Spalding has pointed out, his use of outline owes more to the illustrations of Kate Greenaway than to post-impressionism.22 The figures are certainly linear and decorative like those by the other artists, and the stylised ripples of the water reflect those in Duncan Grant’s panel Bathing (fig.2). Yet Rutherston’s pictorial composition is based on a classically pyramidal format whereas the other murals reveal more primitive influences. There is perhaps a similarity between this triangular figurative arrangement and Augustus John’s painting, The Way Down to the Sea 1909–11 (private collection),23 an early version of which was exhibited at the New English Art Club in 1909. The pose of the child on the left-hand side of Rutherston’s design is a mirror-image of the boy on the right-hand side of John’s.

Approach and reception

Rutherston seems to have been generally unwilling to conform to the spirit and limitations of the communal project. Bernard Adeney recalled: ‘We were working with a limited palette, but when Albert came along he annoyingly made it a condition that he should have vermilion for his girls lips.’24 Rutherston also signed his canvas ‘Albert R.’, in opposition to Fry’s intention that individual recognition should be subsumed by the group spirit in which the murals were executed. In an article in the Pall Mall Gazette in 1913, Fry is quoted as saying:

I hope to get a group of young artists to work together, freely criticising one another, and using one another’s ideas without stint. I think it very important that they should work together in this way, and that we should cease to insist on the extreme individuality of artists. This was borne in upon me very much when I got a group of young artists to decorate the Borough Polytechnic. They all worked together, taking their ideas from one another, developing them along their own lines, and feeling so thoroughly all the time that the work was a common effort that they refused to sign the pictures, saying ‘No, these we did together; let there be no individual signatures.’25

In fact both Duncan Grant and Rutherston signed their canvases. Grant partially concealed his name amidst dots of paint along one of the wavy lines of water in Bathing (fig.2) but he was persuaded by Fry to paint it out.26 Mysteriously, Rutherston’s signature appears to have been unchallenged and his panel remained the only one to be signed by its creator.

Rutherston’s individualistic approach to participation in the Borough Polytechnic project perhaps indicates his general dislike of artistic cliques, evident in his deliberate avoidance of membership of the Camden Town Group. It is interesting to note that although the critic of the Spectator described Rutherston’s design as revealing a ‘Fitzroy twist’,27 the panel is actually representative of the artist’s deliberate isolation from the Fitzroy Street Group. By 1911 Rutherston had distanced himself so completely from that circle that just two years later he was unsuccessful in his attempts to secure election to the ultimate synthesis of Fitzroy Street and Camden Town, the London Group. Gleadowe wrote of him: ‘There was never an artist who, for all his sympathy and sociability, more eschewed dogmas, creeds, schools and shibboleths.’28 This desire to stand independently from his contemporaries possibly originated in a determination to escape from the shadow of his more famous brother, William Rothenstein,29 but Rutherston also seems to have been temperamentally unsuited to working as a member of a group. In 1920 he was one of six artists to participate in Michael Sadler’s project to decorate Leeds Town Hall with murals by modern artists. The scheme was abandoned when Sadler decided that the submitted designs lacked unity and relations between some of the protagonists became quite acrimonious. Rutherston in particular seems to have caused problems by his involvement during the proceedings and Sadler wrote of him: ‘Albert Rutherston has a gift for putting other people at inconvenience ... Frankly, I am not inclined to spend a penny on this creature, because I think he has shown bad spirit in the business and has stirred up better people than himself to be awkward.’30

Rutherston’s individualistic approach to participation in the Borough Polytechnic project perhaps indicates his general dislike of artistic cliques, evident in his deliberate avoidance of membership of the Camden Town Group. It is interesting to note that although the critic of the Spectator described Rutherston’s design as revealing a ‘Fitzroy twist’,27 the panel is actually representative of the artist’s deliberate isolation from the Fitzroy Street Group. By 1911 Rutherston had distanced himself so completely from that circle that just two years later he was unsuccessful in his attempts to secure election to the ultimate synthesis of Fitzroy Street and Camden Town, the London Group. Gleadowe wrote of him: ‘There was never an artist who, for all his sympathy and sociability, more eschewed dogmas, creeds, schools and shibboleths.’28 This desire to stand independently from his contemporaries possibly originated in a determination to escape from the shadow of his more famous brother, William Rothenstein,29 but Rutherston also seems to have been temperamentally unsuited to working as a member of a group. In 1920 he was one of six artists to participate in Michael Sadler’s project to decorate Leeds Town Hall with murals by modern artists. The scheme was abandoned when Sadler decided that the submitted designs lacked unity and relations between some of the protagonists became quite acrimonious. Rutherston in particular seems to have caused problems by his involvement during the proceedings and Sadler wrote of him: ‘Albert Rutherston has a gift for putting other people at inconvenience ... Frankly, I am not inclined to spend a penny on this creature, because I think he has shown bad spirit in the business and has stirred up better people than himself to be awkward.’30

Like all art at this time reflecting modernist sympathies, the Borough Polytechnic murals received a predictably mixed critical reception from the conservative British public, still trying to assimilate the shock of the first post-impressionist exhibition, organised by Roger Fry at the Grafton Galleries in 1910. Some of the commentary was favourable, and Duncan Grant’s Bathing was widely perceived to be the most successful of the painted designs. The Evening Standard hailed the panels as ‘the most important artistic event of 1911’. The critic of the National Review, however, identified only as ‘A Post-Impressionist Scribbler’, completely condemned the scheme, fearing that the ‘repellent’ panels would actually have a corrupting effect on the polytechnic’s working-class students and writing that ‘the perpetrators of these travesties of decoration are more to be pitied than blamed’.31 Fry at least was pleased with the attention the scheme attracted, writing to his mother:

My work at the Borough Polytechnic has been a great success, at least in arousing interest. They had a great debate on it the other night which I was asked to open. It was a very amusing occasion with much freedom of speech, but on the whole they seemed inclined to be converted to my view. The Press has been almost entirely on my side.32

Unfortunately, the content of Fry’s speech about the murals to the polytechnic has not been recorded but in her biography of her Bloomsbury friend, Virginia Woolf wrote that the project was an attempt by Fry to put into practice his views on the relationship of art to society.33 These views were expressed in his 1912 essay ‘Art and Socialism’ in which he wrote that ‘the greatest art has always been communal, the expression – in highly individualised ways no doubt – of common aspirations and ideals’.34 Fry’s ideas on cooperative artistic production achieved much greater fulfilment in his next ambitious project, the Omega Workshops, which opened in Fitzroy Square in 1913 and employed artists to produce painted furniture, textiles and other decorative objects with a modern flavour. Among the Omega designers were Borough Polytechnic veterans Duncan Grant and Frederick Etchells. However, unsurprisingly, given his resistant attitude towards the principles of his previous team project, Albert Rutherston was not invited to participate.

Despite Fry’s assertion that the inhabitants of the Borough Polytechnic had responded favourably to his vindication of the scheme, the murals were never really popular with the institution’s students and staff. The Secretary of the Governing Body who was in office at the time the murals were painted recalled that although they aroused considerable interest in the art world and ‘people came from all parts of the kingdom to see this example of post-impressionism on a large scale’, the decorations did not impress the members and students.35 He went on:

As an example of contemporary life I thought the pictures failed to show this. It is true that the English people take their pleasures sadly, but not so miserably as this lot. Roger Fry’s picture of the elephant rides at the Zoo showed children apprehensive of falling off. Duncan Grant’s bathers in the Serps [sic] showed a man standing on the diving board while his hands were already in the water. Coconut shies on Hampstead Heath showed another dismal lot and only Max Gill’s Punch and Judy show really relieved the gloom.36

Between 1925 and 1930 the Polytechnic underwent a significant expansion and the building was subject to extensive structural change.37 In 1929 the panels were removed from their original hanging space when the dining room was demolished for rebuilding and the decision was taken by the polytechnic not to relocate them elsewhere on the premises. They were offered up for sale to various institutions but nowhere was keen to purchase them. Roger Fry, with the consent of the director, James Bolivar Manson, arranged for them to be ‘temporarily and unofficially’ stored in the basement of the Tate Gallery,38 and at some point a nominal fee of £20 was paid for the murals to remain in the collection permanently.39

In spite of their unpopularity, their ignominious departure from their original home and rather back-door entry into the collection at the Tate, the Borough Polytechnic murals did represent a significant moment in the development of British modernism and had an important legacy for the integration of avant-garde art into the public arena in the early twentieth century. As the art historian Richard Cork has argued, the murals were the first in a chain of public art schemes in Britain which included the Cabaret Theatre Club decorations by Ginner, Gore and others (see Tate T00446) in 1912, the Post-Impressionist Room by the Omega Workshop at the 1913 Ideal Home Exhibition, and Wyndham Lewis’s vorticist decorations at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel in c.1915.40 As a work representative of the art of Albert Rutherston, however, Paddling is not a good example. The distinctive elements of his post-1910 illustrative style are evident, although premature, in the panel, but these were much more attractive and successful in small-scale projects such as book illustration and in his important collaboration with Harley Granville-Barker in theatre design.

Nicola Moorby

October 2003

Notes

Information supplied by Dr Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, Archives and Records Officer, London South Bank University, January 2004.

Frederick J. Packer, Secretary and Clerk to the Governing Body, Borough Polytechnic, letter to Mary Chamot, 15 January 1954, Tate Catalogue file.

Frances Spalding, ‘The Borough Polytechnic Decorations 1911’, unpublished manuscript, Tate Archive TGA 7025.

Judith Collins, ‘“The Influence of the Borough Murals on British Artistic Life”: A Special Lecture’, 14 January 1993, Tate Archive TAV 1190A.

Forty-Fifth Exhibition of Modern Pictures by the New English Art Club, Galleries of the Royal Society of British Artists, London, May–June 1911 (56).

Quoted in Christopher Green (ed.), Art Made Modern: Roger Fry’s Vision of Art, exhibition catalogue, Courtauld Gallery, London 1999, p.79.

Stephen Hackney, Rica Jones, Joyce Townsend (eds.), Paint and Purpose: A Study of Technique in British Art, London 1999, p.113.

Albert Rutherston, ‘From Orpen and Gore to the Camden Town Group’, Burlington Magazine, vol.83, no.485, August 1943, p.201.

Frederick J. Packer, Secretary and Clerk to the Governing Body, Borough Polytechnic, letter to Mary Chamot, 15 January 1954, Tate Catalogue file.

Information supplied by Dr Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, Archives and Records Officer, London South Bank University, January 2004.

Related biographies

Related essays

- Leisure Interiors in the Work of the Camden Town Group Jonathan Black, Fiona Fisher and Penny Sparke

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Albert Rutherston, ‘From Orpen and Gore to the Camden Town Group’ The Burlington Magazine, vol.83, no.485, August 1943, pp.201–5.

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Paddling 1911 by Albert Rutherston’, catalogue entry, October 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www