Charles Ginner La Vieille Balayeuse, Dieppe 1913

Charles Ginner,

La Vieille Balayeuse, Dieppe

1913

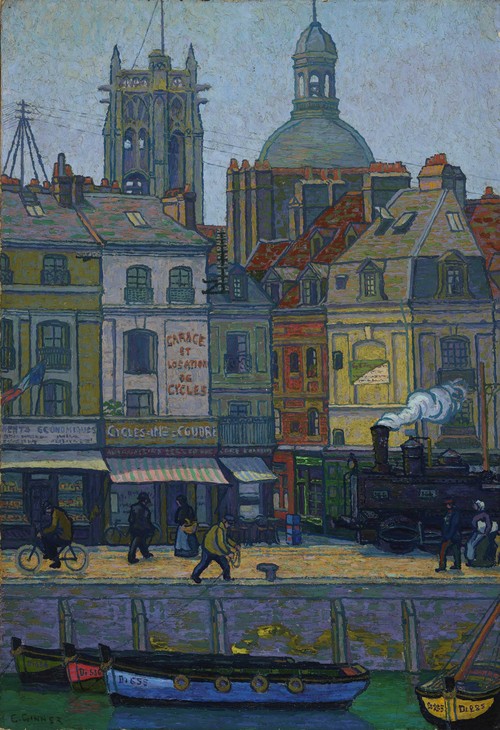

Ginner’s painting depicts a crowd gathered in the Fish Market beside the Avant Port in Dieppe. In the centre of the work the old street sweeper of the title brushes the road. On the left, an old fisherwoman stands with hands on hips, carrying a large fish basket on her back, while to the right a young, middle class woman wearing a bright red jacket looks in the opposite direction. Characteristically, Ginner has painted the foreground and background in a consistent level of detail.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

La Vieille Balayeuse, Dieppe

1913

Oil paint on canvas

630 x 480 mm

Inscribed ‘C. GINNER’ bottom right

Accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax and allocated to Tate 2010

T13025

1913

Oil paint on canvas

630 x 480 mm

Inscribed ‘C. GINNER’ bottom right

Accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax and allocated to Tate 2010

T13025

Ownership history

Exchanged with the artist Robert Bevan for the latter’s The Town Field, Horsgate 1914 (Reading Museum Service); by descent to the artist’s son, Robert Alexander Bevan (1901–1974) and thence by descent to his wife Natalie (1909–2007); accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax and allocated to Tate 2010.

Exhibition history

1913

Fitzroy Street Group display, 19 Fitzroy Street, London, 1913.

1913–14

Exhibition of the Work of English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others, Public Art Galleries, Brighton, December 1913–January 1914 (26).

1914

First Exhibition of Works by Members of the London Group, Goupil Gallery, London, March 1914 (19, £30).

1914

An Exhibition of Paintings by Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner, Goupil Gallery, London, April–May 1914 (43, £30, reproduced).

c.1914–15

Cumberland Market Group display, 49 Cumberland Market, London, c.1914–15.

1915

Exhibition of Works by Members of the Cumberland Market Group, Goupil Gallery, London, April–May 1915 (1, £25).

c.1915–19

Cumberland Market Group display, Grey Room, Goupil Gallery, London, c.1915–19.

1951

The Camden Town Group, Southampton Art Gallery, June–July 1951 (43, reproduced).

1952

Paintings by Edwardian Artists, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, September–October 1952 (13, as ‘Les Balayeuses, Dieppe’).

1953

Edwardian Paintings, Cumberland House Museum and Art Gallery, Southsea, April–May 1953 (13, as ‘Les Balayeuses, Dieppe’).

1953

Paintings by Edwardian Artists, Borough of Mansfield Museum and Art Gallery, August–September 1953 (13, as ‘Les Balayeuses, Dieppe’).

1953–4

Charles Ginner 1878–1952, (Arts Council tour), Darlington Art Gallery, November 1953, Bristol Art Gallery, November–December 1953, Carlisle Art Gallery, January 1954, Tate Gallery, London, January–February 1954, Southampton Art Gallery, February–March 1954, Assembly House, Norwich, March–April 1954 (5, as ‘La Balayeuse, Dieppe’).

1955

The Artists and the Café Royal, Café Royal, London, July 1955 (20, as ‘La Balayeuse’).

1961

Camden Town Group Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition, The Minories, Colchester, September 1961 (20, as ‘La Balayeuse, Dieppe’).

1964

London Group 1914–64: Jubilee Exhibition, (Arts Council tour), Tate Gallery, London, July–August 1964, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, August–September 1964, Doncaster Museum and Art Gallery, October 1964 (17).

1965

Decade 1910–20, (Arts Council tour), Leeds City Art Gallery, May 1965, Reading Art Gallery, May–June 1965, Manchester City Art Gallery, July 1965, Glasgow Art Gallery and Museum, July–August 1965, Leicester Museum and Art Gallery, September 1965 (44, as ‘La Balayeuse, Dieppe’).

1975

English Paintings from the Bevan Collection, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London, April–May 1975 (15).

1975

The R.A. Bevan Collection from Boxted House, The Minories, Colchester, July–August 1975 (73).

1978

The Bevan Collection: A Selection of Paintings by British Artists including the Camden Town Group and a Memorial Tribute to John Nash, Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury, Suffolk, August 1978 (36).

1980

The Camden Town Group, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, April–June 1980 (43, reproduced).

1986

The New English Art Club Centenary Exhibition, Christie’s, London, August–September 1986 (166, reproduced).

1992

Rendez-vous à Dieppe, Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, May–June 1992 (30, reproduced p.27).

2008

A Countryman in Town: Robert Bevan and the Cumberland Market Group, Southampton City Art Gallery, September–December 2008 (no number).

2008–10

From Sickert to Gertler: Modern British Art from Boxted House, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, March–June 2008, Brighton Art Gallery and Museums, April–September 2010 (24, reproduced).

References

1914

T.E. Hulme, ‘Modern Art – III. The London Group’, New Age, 26 March 1914, p.661.

1922

Gerrard Gwathmey, ‘A Group of English Art Rebels: Gilman, Ginner, Bevan and Others and What They Stand For’, Arts and Decoration, August 1922, reproduced p.252.

1954

‘Charles Ginner: Memorial Exhibition at the Tate’, Times, 20 January 1954, p.8.

1976

Richard Cork, ‘Hulme the Critic and Champion of Bomberg’, Vorticism and Abstract Art in the First Machine Age, vol.1, Berkley and Los Angeles 1976, p.186.

1981

Andrew Causey, ‘Harold Gilman: An Englishman and Post-Impressionism’, in Harold Gilman 1876–1919, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1981, p.14.

1995

Denys J. Wilcox, The London Group, 1913–1939: The Artists and their Works, Aldershot 1995, p.86.

2008

Alice Strang, ‘Bobby and Natalie Bevan and the Art at Boxted House’, in From Sickert to Gertler: Modern British Art from Boxted House, exhibition catalogue, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh 2008, p.13.

2008

Frances Stenlake, Robert Bevan: From Gauguin to Camden Town, London 2008, pp.115–6, reproduced p.117.

Technique and condition

La Vieille Balayeuse, Dieppe is painted in artists’ oil paints on one piece of commercially primed canvas on a four-member stretcher. The textile support is woven in an open plain tabby-weave and may be linen; a faint oval colourman’s stamp in black letters is centred on the reverse, which reads:

AUX BEAUX ARTS

ENCADREMENTS

R. POUYER

91, GRANDE RUE

DIEPPE

FOURNITURES pour les ARTS et la PHOTO

ENCADREMENTS

R. POUYER

91, GRANDE RUE

DIEPPE

FOURNITURES pour les ARTS et la PHOTO

The entire last row is faint and illegible but the same stamp appears in full on the reverse of Le Quai Duquesne 1913 (private collection, Canada).1 The evenly applied off-white priming extends to the cut edges and retains the canvas weave texture.

Dark grey lines in a graphite medium at the tacking margins could relate to preparatory work, like squaring-up the image area for drawing. For capturing the image, Ginner used a home-made view-finder which was subdivided by threads. For many of his paintings he created exhaustive pencil drawings which he squared up afterwards and numbered the areas for enlargement on canvas. Together with written colour notes, the painting was finally carried out.

In the crevices between brushstrokes, dark blue lines can be seen which could relate to the initial drawing. A thin wash of underpainting is visible along the right edge, showing approximately the colour of the paint layer: light blue for the sky and light violet for the roofs. He did not apply a coloured wash for the street.

Ginner worked from the left to the right side and applied the thick paint as a stiff paste using short brushstrokes. The paint was brushed within determined forms and ridges of paint at the boundaries between the forms. The colours did not intermix although they were applied wet into and onto another. He used the stiffness of the paint to model the outlines of the forms and to vary the surface texture. Where brushstrokes abut and overlap, small crevices and gaps appear. Peaks of impasto express the movement of the sky and the vibrant life taking place on the street. The lighter hues such as in the sky or the road appear generally more matt than the more fluid dark blue colours used for outlines. The latter were mixed with paint medium which retains their saturation and creates a glossier surface and softened brush marks. In some areas the outlines are affected by surface blanching.

Along the top edge, four holes are pierced through the canvas and may indicate that the painting was fixed during or shortly after the painting process. The area of paint surrounding the hole in the top-right corner is squashed and abraded, perhaps relating to a spacer attached for the drying process. The painting is unvarnished and shows the varying gloss of the several colours used. It is signed ‘C. GINNER’ in light blue oil paint in the bottom-right corner.

Simone Wernitznig

March 2010

Notes

How to cite

Simone Wernitznig, 'Technique and Condition', March 2010, in Helena Bonett, ‘La Vieille Balayeuse, Dieppe 1913 by Charles Ginner’, catalogue entry, August 2011, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Description

The title of this painting translates from the French as The Old Street Sweeper, Dieppe. The line of a tall lamp-post leads the viewer’s eye down towards the sweeper, positioned in the centre foreground of the composition, as the focus of the painting. Behind her a small crowd is gathered on the pavement; the heads of a few people behind the group face outwards, suggesting that they are selling produce, most probably fish, to the rest. The presence of the electric light dominating the middle ground in favour of the smaller gas lamp suggests an encroaching modernity to this traditional market scene.

Characteristically for Ginner, the fore-, middle- and backgrounds are painted in almost the same level of detail and focus, with tiles on the roofs in the background individually articulated. A sense of depth is created instead by the use of pale hues in the background in contrast to stronger colours in the foreground. Influenced by Vincent van Gogh, Ginner often used complementary colours in his work. In this case, purple and yellow are the most prominent, while the bright red of the young woman’s jacket on the right complements the green of the apron of a small girl who stands in the crowd, thus uniting the two; their poses mirror one another also.

The location of the scene is the Fish Market beside the Avant Port where the Arc Poissonnerie and the Quai Henri IV meet in the town of Dieppe in northern France.1 The houses in the background on the Quai Henri IV are depicted accurately, as can be seen in photographs from the time.2 The sweeper is using a typical French street broom made out of tied twigs of birch or broom. Traditionally, pavements would be swept in a swinging gesture, picking up water from the gutter to brush the damp head onto the pavement in a rhythmic fashion.3

The scene encompasses a diverse range of people in age, class and work in a similar fashion to Ginner’s Piccadilly Circus of 1912 (Tate T03096). To the left of the painting an old fisherwoman in traditional working clothes and apron stands with hands on hips facing out of the picture with a large fish basket on her back; on the right a young, middle class woman in modern smart clothes, who may be a tourist, faces in the opposite direction. Together with the sweeper, they create a triangular formation. The casual poses of the other figures, with men in working clothes standing with hands in pockets, creates an atmosphere of working class life similar to Robert Bevan’s paintings of crowds at horse sales in such works as Horse Sale at the Barbican 1912 (Tate N04750, fig.1) and Under the Hammer 1914 (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool).4

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

Horse Sale at the Barbican 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 787 x 1219 mm; frame: 1090 x 1444 x 93 mm

Tate N04750

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1934

Fig.1

Robert Bevan

Horse Sale at the Barbican 1912

Tate N04750

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Le Quai Duquesne, Dieppe 1913

Oil paint on canvas

629 x 432 mm

Private collection, Vancouver

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © heffel.com

Fig.2

Charles Ginner

Le Quai Duquesne, Dieppe 1913

Private collection, Vancouver

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © heffel.com

According to his notebooks, La Vieille Balayeuse is one of three works Ginner painted on his visit to the Normandy town in 1913.5 The others are The Trawlers, Dieppe (whereabouts unknown) and Le Quai Duquesne, Dieppe (fig.2). The latter depicts the Quai Duquesne, which is at the south end of the Arc Poissonnerie, so very close to the location shown in La Vieille Balayeuse. The painting shows a view towards the church of St Jacques and was probably painted from the opposite side of the Bassin Duquesne. While the focus of the Tate painting is the figures in a crowd, Le Quai Duquesne presents a vertical cross-section of the street, including a train (at the time the train from Paris ran right up to the Quai Henri IV to a station called the Gare Maritime). In his notebooks Ginner recorded that he painted pochades, or small colour sketches, for both of these works (the pochade for Le Quai Duquesne is in the collection of Museums Sheffield).6 According to the notebooks, the three paintings were shown at the same exhibitions over the next few years.

Dieppe

In the early nineteenth century, Dieppe became an important destination for artists and later a fashionable resort for tourists. Ginner’s fellow Camden Town Group colleague, Walter Sickert, was a resident of the town and its environs for many years and visited often throughout his life. Sickert drew and painted many architectural scenes, such as Les Arcades de la Poissonnerie, Dieppe c.1900 (Tate N05045), and people in interiors, such as Female Figures in the Café Suisse, Dieppe c.1914 (Tate Archive TGA 8120/3/16), but he produced no depictions of crowds outside as Ginner does here.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Evening, Dieppe 1911

Oil on canvas

610 x 463 mm

Private collection, by courtesy of MacConnal-Mason Gallery

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © MacConnal-Mason Gallery

Fig.3

Charles Ginner

Evening, Dieppe 1911

Private collection, by courtesy of MacConnal-Mason Gallery

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © MacConnal-Mason Gallery

Ginner was a native of France, having been born in Cannes to English and Scottish parents. He trained in Paris before moving to London in 1910 where he met the artists who went on to form the Camden Town Group. With one of these artists, Harold Gilman, Ginner visited Dieppe on their way back from Paris in 1911. On that occasion the pair painted works including Gilman’s Le Pont Tournant (The Swing Bridge) (private collection)9 and Ginner’s complementary townscapes, The Sunlit Quay (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool)10 and Evening, Dieppe (fig.3). These were all exhibited at the second Camden Town Group show in December that year. La Vieille Balayeuse was painted on another trip to Dieppe in 1913.

Exhibition and reception

Ginner kept records of all of his pictures, including where they were exhibited and to whom they were sold.11 La Vieille Balayeuse, Dieppe was shown at two key exhibitions of the period: Exhibition of the Work of English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others at the Brighton Public Art Galleries from December 1913 to January 1914 and the first London Group show at the Goupil Gallery in March 1914. The Brighton show was organised by Spencer Gore with the original title Exhibition by the Camden Town Group and Others, but it ultimately became a platform for the ‘Cubists’, in particular Wyndham Lewis, to promote their work. The London Group was formed around this time as an expansion of the Camden Town Group to include more than its sixteen, all-male painters.

In a review of the London Group exhibition, the influential critic T.E. Hulme stated:

Mr. Charles Ginner’s ‘La Balayeuse’ is the best picture of his that I have seen as yet. His peculiar method is here extraordinarily successful in conveying the sordid feeling of the subject.12

Hulme had recently begun writing about modern art for the New Age, promoting the more abstract movement in painting and sculpture that became vorticism later that year. Although Hulme is usually associated with the vorticists, the groupings were more interconnected than commonly perceived. Ginner was a frequent visitor to Hulme’s Tuesday night salons at 67 Frith Street, where art was commonly debated.13 Such debates may have inspired Ginner to publicly proclaim his views in his manifesto on ‘Neo-Realism’, which was published in the New Age on 1 January 1914. In this article, Ginner extolled realism in painting, decrying much artistic output as merely ‘academic movements ... based on formula’,14 including the new cubist work that he saw as an imitation of Paul Cézanne, and therefore formulaic. In contrast, he underlined the need for the painter to have a ‘direct intercourse with Nature’, writing:

Each age has its landscape, its atmosphere, its cities, its people. Realism, loving Life, loving its Age, interprets its Epoch by extracting from it the very essence of all it contains of great or of weak, of beautiful or of sordid, according to the individual temperament. Realism is thus not only a present intimate revelation of its own time, but becomes a document for future ages. It attaches itself to history.15

Ginner thus presented his argument for realism. However, it was precisely the documentary facts that Hulme found troubling in his view of Camden Town Group paintings:

They are full of detail which is entirely accidental in character, and only justified by the fact that these accidents did actually occur in the particular piece of nature which was being painted. One feels a repugnance to such accidents and desires painting where nothing is accidental, where all the contours are closely knit together into definite structural shapes.16

In this fashion, Hulme articulated an argument for abstraction over realism. Ginner’s article on Neo-Realism had in fact pushed Hulme towards articulating this more radical view of abstraction.17 On 12 February 1914 Hulme wrote a long article in response to Ginner’s manifesto, finding that:

Two statements are confused: (1) that the source of imagination must be nature, and (2) the consequence illegitimately drawn from this, that the resulting work must be realistic, and based on natural forms.18

Instead, Hulme stated that:

It is true, then, that an artist can only keep his work alive by research into nature, but that does not prove that realism is the only legitimate form of art.

Both realism and abstraction, then, can only be engendered out of nature, but while the first’s only idea of living seems to be that of hanging on to its progenitor, the second cuts its umbilical cord.19

Both realism and abstraction, then, can only be engendered out of nature, but while the first’s only idea of living seems to be that of hanging on to its progenitor, the second cuts its umbilical cord.19

Ginner’s ideas on Neo-Realism, together with his detailed style of painting, both inspired Hulme to articulate a new view on art that was to be highly influential among their contemporaries.

Related works and ownership

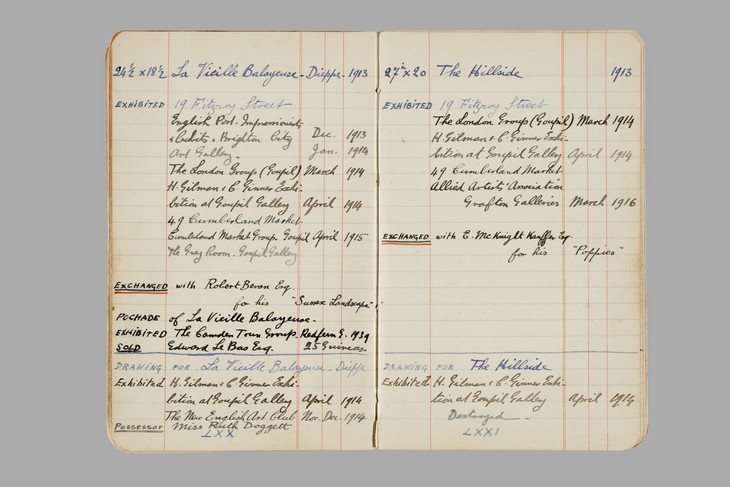

Fig.4

Charles Ginner

List of Paintings, Drawings, Etc. of Charles Ginner. Book I 1910–18

Tate Archive TGA 9319/1

Two studies were made for this work, a drawing and a pochade or small sketch in colour (see fig.4). Ginner recorded that the pochade was exhibited at the Camden Town Group retrospective at the Redfern Gallery in 1939, and was sold for 25 guineas to the artist Edward Le Bas (1904–1966), who had painted a portrait of Ginner in 1930 (private collection).20 The drawing was shown at Ginner’s joint exhibition with Gilman at the Goupil Gallery in April 1914 and at the New English Art Club in November to December 1914; the owner of the drawing was the artist Ruth Doggett (1881–1974), who owned several of his works, and had also shown at the Exhibition of the Work of English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others in Brighton. Doggett was drawn and painted by Gilman around 1915 and Ginner later wrote an introduction to the catalogue of an exhibition of her works at the Fine Art Society in 1934.21

As well as showing La Vieille Balayeuse, Dieppe at four group exhibitions, Ginner recorded that it was also on display at the Fitzroy Street and Cumberland Market group ‘At Homes’, where prospective customers were invited to view the work in private. Ginner gradually decreased its price from £30 at two exhibitions in 1914 to £25 at the Cumberland Market Group exhibition in 1915, but, despite this, it still failed to secure a buyer. He eventually exchanged it with his fellow Camden Town and Cumberland Market group colleague, Robert Bevan, for his painting The Town Field, Horsgate 1914 (Reading Museum Service)22 at some point after the final recorded exhibition in 1915. Following Bevan’s death in 1925, Ginner remained good friends with his wife, the artist Stanislawa de Karlowska, and their son, Robert A. Bevan, throughout his life.

Helena Bonett

August 2011

Notes

A map of Dieppe is reproduced in The Dieppe Connection: The Town and its Artists from Turner to Braque, catalogue for the exhibition Rendez-vous à Dieppe, Brighton Museum and Art Gallery 1992, [p.93].

For example, see a photograph of the Avant Port from the turn of the century, reproduced ibid., pp.88–9. The location of this painting is in the centre of the photograph on p.88.

Reproduced at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/walker/collections/20c/bevan.aspx , accessed 7 December 2010.

Tate Archive TGA 9319/1, pp.XI, LXX. See fig.4. Le Quai Duquesne pochade is reproduced at Your Paintings, http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/paintings/le-quai-duquesne-dieppe-france-72198 , accessed 10 August 2011.

Reproduced at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington DC, http://www.corcoran.org/collection/highlights_main_results.asp?ID=29 , accessed 28 December 2010.

Reproduced in Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, no.11.

Reproduced in The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988 (91).

Rebecca Beasley, ‘“A definite meaning”: The Art Criticism of T.E. Hulme’, in Edward P. Comentale and Andrzej Gasiorek (eds.), T.E. Hulme and the Question of Modernism, Aldershot 2006, p.59.

Related biographies

Related essays

- ‘A Definite Meaning’: The Art Criticism of T.E. Hulme Rebecca Beasley

Related catalogue entries

Related archive items

Related reviews and articles

- Charles Ginner, ‘Neo-Realism’ The New Age, 1 January 1914, pp.271–2.

- T.E. Hulme, ‘Modern Art – II. A Preface Note and Neo-Realism’ The New Age, 12 February 1914, pp.467–9.

How to cite

Helena Bonett, ‘La Vieille Balayeuse, Dieppe 1913 by Charles Ginner’, catalogue entry, August 2011, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www