Turner Bequest CCXCI b 1–56

Sketchbook bound in boards, covered in red leather, with a brass clasp, now missing from front cover; leather pencil loops along top and bottom edges inside back cover; bellows-type pocket inside front cover

56 leaves of white wove paper with edges washed in yellow, the first and last being free endpapers, marbled on their outer faces and continuous with the pastedowns; page size 77 x 101 mm

Supplied by Edward Tarbox, London (label inside front cover; see main catalogue entry)

Blind-stamped ‘CCXCI (b)’ front cover, top right

56 leaves of white wove paper with edges washed in yellow, the first and last being free endpapers, marbled on their outer faces and continuous with the pastedowns; page size 77 x 101 mm

Supplied by Edward Tarbox, London (label inside front cover; see main catalogue entry)

Blind-stamped ‘CCXCI (b)’ front cover, top right

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

References

This sketchbook remained undocumented before Finberg’s 1909 Turner Bequest Inventory, when he named it ‘Colour Studies (1)’ and associated it by implication with the Colour Studies (2) sketchbook (Tate; Turner Bequest CCXCI c), dating them both to about 1834.1 Neither includes the usual Turner Bequest executors’ notes and endorsement or a schedule number from the 1854 inventory of Turner’s sketchbooks.2 Presumably they were put aside at the time on account of their sometimes erotic subject matter, which Finberg passed over in titling most pages with neutral variations on ‘colour sketch’ or ‘figure’ subjects.

Perhaps Finberg did not examine the contents closely, as he later guilelessly suggested that the pages ‘torn from a small sketchbook’ which appeared to contain ‘a memorandum in colour that [Turner] had made of the sky and sunset’ to serve as sails for a child’s model ship came from one of the Colour Studies books; this was as recalled in the words of the artist Robert C. Leslie (1826–1901; son of artist Charles Robert Leslie, 1794–1859), and supposedly occurred when he was staying at Petworth House in Sussex as a boy in 1834.3 Based on other primary sources, Ian Warrell has noted that the event was more likely to have happened in the autumn of 1836,4 though whether one of the Colour Studies books was involved remains a moot point, and the unrelated Oxford and Bruges sketchbook (Tate; Turner Bequest CCLXXXVI) is another candidate.5 For more on Petworth, see the overall Introduction to the present grouping.

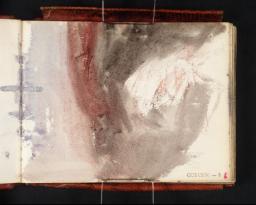

It was not until the 1960s when the two books, along with the Fishing at the Weir sketchbook (Tate; Turner Bequest CCLXXXI), were addressed by Lawrence Gowing in terms of both the erotic character of their contents and their loose, improvisational technique.6 (Insofar as they address the two Colour Studies books in general, sometimes together with Fishing at the Weir, Gowing’s and others’ interpretations and comments as cited in this sketchbook’s literature are set out in the general Introduction to the three books.) Attempting to consider them as a coherent sequence, Raphael Rosenberg has suggested that Colour Studies (2) was filled first, followed by the present book, and concluding with Fishing at the Weir, where the watercolours peter out after the first few pages.7

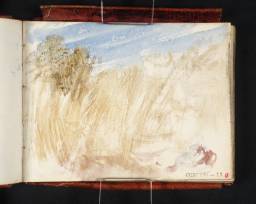

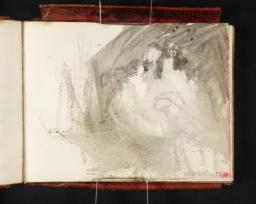

Gerald Wilkinson has described the Colour Studies (1) sketchbook book as ‘claustrophobic, some of the pages very heavily worked with layers of dark watercolour, A great painting of Turner’s may seem to open up and expand before us: this miniature closes us in, mysteriously suggesting in half-revealed images some truth which he could not paint.’8 Anthony Bailey has observed that at ‘fifty-nine or so [Turner] still had a powerful sex-drive, although he didn’t seem altogether free about revealing it, even for his own viewing. Most of these “studies” are not well drawn; only a part of him seems involved. Some have a voyeuristic feeling’.9 Despite others’ reservations about the figure subjects in this book (see the Introduction to the grouping), James Hamilton has nevertheless described them as ‘lyrical’.10 Particularly with regard to the landscapes here, Eric Shanes has commented that this ‘is the type of sketchbook in which Turner clearly explored his memories and imaginings rather than recorded his direct observations’, albeit ‘the visual data is so relatively minimal that the image seems entirely elusive and verges on abstraction.’11

As Warrell has observed, there are various instances of openings with wash across both pages,12 as opposed to the general runs of single pages washed on their rectos or versos at the beginning and end of the book respectively. From folio 22 verso (D28814) onwards, nearly all the leaves are worked on both sides; then, between folios 31 verso and 42 recto (D28829, D28846) double-pages of wash alternate with blank double-pages, as if Turner sought to isolate the works. This may have been for practical reasons, as the washes on some of these pages were particularly heavy and were initially offset in symmetrical or mirror images from one side to the other before being worked into different compositions. Turner appears to have exploited this controlled element of chance deliberately, perhaps in the spirit of Alexander Cozens’s ‘blot’ techniques for suggesting landscape compositions13 or, as Rosenberg has suggested, in an unwitting prefiguring of Klecksography (see the overall Introduction to this grouping).

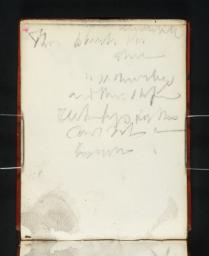

Although most of the works in this sketchbook are variations on bedroom scenes and figures, there are landscape sketches, mostly in the same improvisatory watercolour style, together with a few in pencil: folios 11 recto, 13 recto, 46 verso, 47 recto, 49 recto, 50 verso, 51 verso, 52 verso and 56 recto (D28802, D28804, D28853, D28855, D28859, D28861, D28863, D28865, D28873). There are also pages of written notes: folios 1 verso, 9 verso, 48 verso (D28791, D28800, D28857). Of the landscapes, the watercolours D28863 and D28863 may be studies for a painting exhibited in 1836 or vignette watercolour illustrations of the mid 1830s. Finberg’s date of about 1834 and others of a year or two later in subsequent sources have been taken into account, and the dates have been amended throughout to about 1834–6; this is additionally on account of certain aspects of the Fishing at the Weir sketchbook which indicate that the latter was in use between those dates, which have also been applied to Colour Studies (2).

Technical notes

How to cite

Matthew Imms, ‘Colour Studies (1) Sketchbook c.1834–6’, sketchbook, May 2014, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, September 2014, https://www