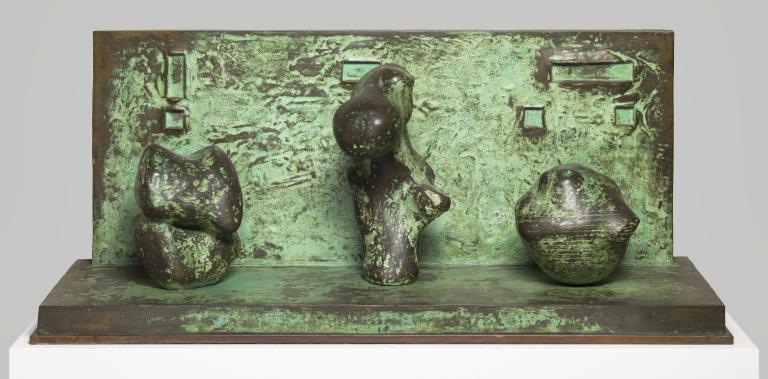

Henry Moore OM, CH Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962

Image 1 of 16

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Three Motives Against Wall No.2

1959, cast 1962

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

This sculpture relates closely to its earlier counterpart Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958 (Tate T03763), which also features three amorphous forms set on a platform in front of a rear wall decorated with rectangular impressions. However, the three central ‘motives’ of is later work are more abstract in form and demonstrate how closely Moore studied the shapes of flint stones when he invented new sculptures.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Three Motives Against Wall No.2

1959, cast 1962

Bronze

460 x 1083 x 381 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Moore’ on side of base

Presented by the artist 1978

Number 10 in an edition of 10 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02281

Three Motives Against Wall No.2

1959, cast 1962

Bronze

460 x 1083 x 381 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Moore’ on side of base

Presented by the artist 1978

Number 10 in an edition of 10 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02281

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1963

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, Ferens Art Gallery, Kingston upon Hull, October–November 1963, no.33.

1965

Henry Moore, Museu de Arte Moderna, Rio de Janeiro, January–February 1965, no.21.

1967–8

Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, October–November 1967; Confederation Art Gallery and Museum, Charlottetown, January–March 1968; Arts and Cultural Centre, St Johns, March–May 1968; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Ottawa, May–June 1968, no.8.

1968

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968 (?another cast exhibited no.107).

1969

Henry Moore Exhibition in Japan, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, August–October 1969, no.44.

1971

Henry Moore: Sculpture, Drawings, Graphics, Turnpike Gallery, Leigh, November–December 1971, no.6.

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, May–August 1977 (?another cast exhibited no.89).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

References

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Gallery, London 1960 (another cast reproduced no.55).

1962

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, M. Knoedler and Co., New York 1962 (another cast reproduced p.34).

1967

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1967 (another cast reproduced no.8).

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.55, reproduced pl.52.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, p.173 (another cast reproduced pl.167).

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973, pp.182–4.

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, exhibition catalogue, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris 1977 (another cast reproduced no.89).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.39.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, pp.152, 159 (original plaster reproduced pl.133).

1980

[Richard Calvocoressi], ‘T.2281, Three Motives against Wall No.2’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.125–6, reproduced p.125.

1983

Henry Moore: 85th Birthday Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Fine Art, London 1983 (another cast reproduced p.49).

1986

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986 (another cast reproduced pls.70–1).

1986

Henry Moore: Model to Monument, exhibition catalogue, Kent Fine Art, New York 1986 (another cast reproduced pp.13–14).

2002

Henry Moore: Rétrospective, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul 2002 (another cast reproduced p.176).

2002

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Valenciennes, Valenciennes 2002 (another cast reproduced p.67).

2005

David Mitchinson (ed.), Henry Moore and the Challenge of Architecture, Much Hadam 2005 (another cast reproduced no.101).

2006

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Three Motives against Wall No.2’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.258 (another cast reproduced, pl.186).

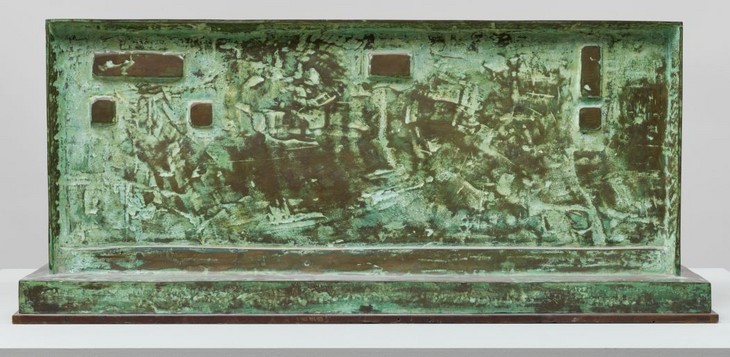

Technique and condition

This bronze sculpture consists of three amorphous forms positioned within a stage-like setting. A single L-shaped component forms a rectangular base with vertical a backdrop. The figures to the centre and right are each attached to the base with one bolt. The figure on the left should have been attached with two bolts but one has been lost causing it to swivel. Conservation reports suggest that some fixings have become loose, so it is possible that the three forms are not orientated as the artist originally intended. However, the dearth of early photographic documentation of this sculpture makes this difficult to confirm.

Some yellowed adhesive is visible underneath the base of the form on the left that is not thought to be original. It is more likely to be the remains of a substance used to prevent the figure from swivelling. The sculpture is coloured a vivid bright green with dark brown highlights and it rests on a wooden plywood mount clad with copper sheet to which it is fixed using two bolts at either end.

Moore would have made each of the original elements in plaster (fig.1) and would perhaps have spent time positioning them in different configurations before settling on the final arrangement. He textured the plaster using a combination of tools and it is possible to see horizontal incisions and marks made using saw blades. The texture of the backdrop suggests that Moore made this section using either clay or plaster, which he freely applied, before impressing rectangles into the surface to create a decorative pattern. The high points of the forms have been smoothed, probably by using abrasives when the plaster was dry. Once complete, a mould was taken from the plaster original that was then used to cast it in bronze.

Henry Moore

Three Motives Against a Wall No.2 1958

Plaster

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Three Motives Against a Wall No.2 1958

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

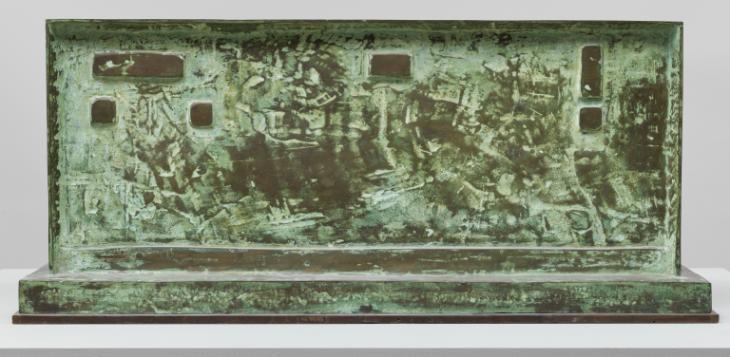

Back of rear wall of Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1958, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Back of rear wall of Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1958, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The level of detail on the bronze figures suggests that they were fabricated using the lost wax technique, whereas the base and backdrop are more likely to have been sand cast, as is revealed by the slightly granular texture of the surface at the back (fig.2).1 Small flaws in the casting are often repaired with a plug of bronze that is then carefully smoothed and textured to match the surrounding surface. An example of such a repair is visible as a circular mark on the middle form (fig.3).

Detail of a repair to Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of a repair to Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of the artist's signature and edition number on Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1958, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of the artist's signature and edition number on Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1958, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After casting the bronze was coloured using a technique known as artificial patination. This process involved applying chemical solutions that reacted with the bronze to create coloured compounds. A dark brown background was applied first using a chemical such as potassium or ammonium polysulphide. This was then followed by the application of a green patina over the top. There are many different patina recipes used to produce green colours on bronzes but they often contain mixtures of copper and ammonium salts dissolved in water. The solution is usually applied in successive layers until the desired colour is achieved. The patinator has lightly abraded the green patina on the high points of the form to reveal the underlying brown colour before a clear wax was applied to consolidate and protect the finished patina.

The bronze is mounted onto a copper-clad wooden base. This sculpture was cast at the Art Bronze Foundry, London, in an edition of ten plus one artist’s cast. It is inscribed ‘Moore 10/10’ on the back right corner at the side (fig.4).

Lyndsey Morgan

November 2012

For a film explaining the lost wax casting method see http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/videos/l/lost-wax-bronze-casting/ , accessed 18 February 2014. Sand casting is a technique whereby a model is buried in sand to create a mould from which the bronze can be cast. Sand casting is quicker and less labour intensive than lost wax casting but generally less suitable for reproducing very intricate shapes or surface details.

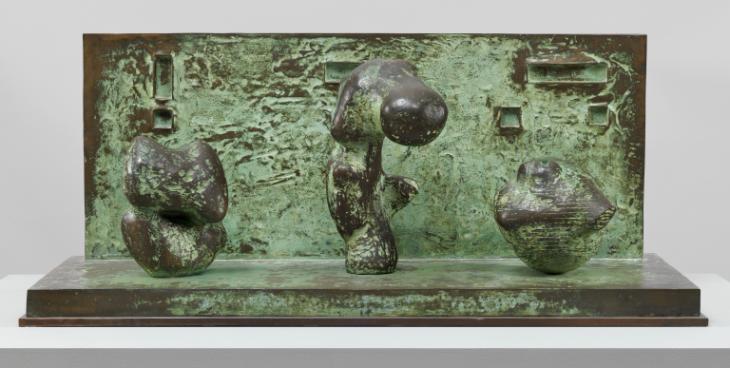

Entry

The bronze sculpture Three Motives Against Wall No.2 comprises three individual amorphous forms positioned in a row on a stage-like platform set against an upright rectangular wall. This wall is imprinted with an arrangement of square and rectangular depressions and is joined to the horizontal platform to create a right-angled unit. The assembled bronze is mounted onto a copper-clad wooden base. The three forms, or motives, sit directly on the bronze base, to which they are attached with a bolt screwed from the underside. This particular subject and composition was first devised by Moore in 1958 when he created Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 (Tate T03763), although there are significant differences between this earlier sculpture and the present work.

Detail of left motive in Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1958, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of left motive in Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1958, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of middle motive in Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of middle motive in Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The motive on the left-hand side is a single entity but comprises two globular, curvaceous forms that appear to be balanced one on top of the other (fig.1). Overall the motive is roughly oval-shaped, although from the front it appears as though two u-shaped forms have been slotted together leaving a small recess in the centre. The top edge of the motive dips slightly in the middle creating a concave curve, while the front is rounded and projects forward. By contrast, the middle motive consists of a thin, tubular shaft that rises vertically upwards from the base and is punctuated by two short protrusions, or stumps, on alternate sides (fig.2). The top of the shaft curves forwards at a right angle and culminates in a long, bulbous protrusion that makes the motive seem top heavy.

The right hand motive takes the form of a roughly-shaped sphere from which several bulbous protrusions emerge, encircling the object (fig.3). The top of this motive, however, is flat, as though the apex of the sphere has been sliced off. A notable feature of this motive is the sequence of parallel lines or rings that have been incised into the surface and run horizontally around the circumference. Although tool marks are visible on the other two motives, neither of them have been marked or patterned in a similar way to this right hand form.

A series of square and rectangular depressions decorate the rear wall, the surface of which is generally rough, suggesting that this element of the sculpture was cast from a plaster original (fig.4). Overall the sculpture is coloured with a vivid green patina. It has been signed ‘Moore’ and is numbered ‘10/10’ towards the rear of the right edge (fig.5).

Detail of rear wall in Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1958, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of rear wall in Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1958, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of the artist's signature and edition number on Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1958, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of the artist's signature and edition number on Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1958, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From plaster to bronze

Henry Moore

Three Motives Against a Wall No.2 1958

Plaster

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Three Motives Against a Wall No.2 1958

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore started collecting pebbles, shells and bones in the late 1920s and his sketch books from the 1930s contain studies of these natural forms, many of which are transformed into figures. The curator David Sylvester noted that Moore was attracted to organic forms ‘because of their potential for evoking things other than themselves, so that shapes derived from them could have a mysterious ambiguity’.2 By the late 1950s, when Three Motives Against Wall No.2 was created, Moore had all but eliminated the practice of making preparatory drawings for his sculptures, preferring instead to make small three-dimensional plaster models. According to Sylvester, ‘a high proportion of the [plaster] sketch-models have had as their point of departure a found pebble or bone or fragment of bone, while others have been made up while looking at pebbles and bones – as well, of course, as while remembering them’.3 When asked in 1960 how he arrived at an idea for a sculpture, Moore replied:

Well, in various ways. One doesn’t know really how ideas will come. But I can induce them by starting with looking at a box of pebbles. I have collected bits of pebbles, bits of bone, found objects, and so on, all of which help to give an atmosphere to start working. Then with those pebbles ... I sit down and something begins.4

Importantly, Sylvester noted that the stones and pebbles examined by Moore in the 1950s were different from those looked at in the 1930s. Unlike the smooth pebbles that informed the rounded elements of sculptures such as Four Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934 (Tate T02054) by the 1950s Moore was looking at ‘the sort of pebbles found inland – flints with sharply undulating contours and corners broken off leaving a jagged facet ... The objects are altogether rougher, more irregular, than before’.5

Photograph of stones in Moore's studio

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Photograph of stones in Moore's studio

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Maquette for Left Hand Form in Three Motives Against a Wall No.2 1959

Plaster

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Maquette for Left Hand Form in Three Motives Against a Wall No.2 1959

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In 1987 the curator Alan Wilkinson asserted that the three forms in Three Motives Against Wall No.2 ‘were undoubtedly based on flint stones in the artist’s studio’.6 In particular, he identified a photograph of stones from Moore’s studio which includes a flint that closely resembles the middle motive of the sculpture (fig.7). This flint stone, positioned second from the right in the photograph, has truncated arm-like protrusions and a large bulbous head that curves forward at a right angle just like the central tall motive.7 Although Moore would often modify his flints and bones with additions and alternations in plaster, Wilkinson argued that in this instance he used the flint with ‘little alteration’.8 In 1963 he explained to Sylvester how he worked with found natural objects:

I look at them, handle them, see them from all round, and I may press then into clay and pour plaster into that clay and get a start as a bit of plaster, which is a reproduction of the object. And then add to it, change it. In that sort of way something turns out in the end that you could never have thought of the day before. This to me now is the beauty of each day if one’s working – that by the end of it you might have had something happen that you couldn’t possibly have foreseen.9

It is likely that in order to make the middle motive, Moore made a reproduction of the flint stone, and then, once the plaster had hardened, he accentuated and added forms, such as the two small protrusions on the top of the sculpture.

An additional plaster maquette also exists of the left-hand motive of Three Motives Against Wall No.2 (fig.8). According to Wilkinson ‘the surface of the plaster has been marked in pencil with points of reference for enlarging the maquette’, suggesting that at one stage Moore was thinking about producing this particular sculpture on a larger scale.10 Although this idea never materialised and the maquette was not cast in bronze, the basic form of this sculpture, which comprises two balanced or interconnected elements, may have provided a starting point for Moore’s larger sculpture Locking Piece 1963–4 (Tate T02293).

When they were completed Moore sent the plaster components to a professional foundry to be cast in bronze. The three motives were cast separately while the base and back wall appear to have been cast as a single piece. Records held at the Henry Moore Foundation reveal that Three Motives Against Wall No.2 was cast at the Art Bronze Foundry in London, in an edition of ten plus one artist’s proof. Not all of the examples in the edition were cast at the same time. The date of Tate’s cast is known from a bill issued by the foundry dated 7 June 1962 that lists ‘Wall & Motives, 10/10, £200’ among the items cast for Moore that month.11 It is likely that Moore first came into contact with the foundry when he was Head of the Sculpture Department at Chelsea College of Art in the 1930s because it was located close to the college and was used regularly by staff and students.

At the foundry the technicians would have used the original plasters to create hollow moulds into which molten bronze could be poured, and from which the multiple bronze versions could be made. While the three motives were most likely cast using the lost wax method, the base and the backdrop were probably cast using the sand casting method because the grainy texture on the back of the rear wall is typical of this casting procedure.

Detail of patina on right motive in Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1958, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Detail of patina on right motive in Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1958, cast 1962

Tate T02281

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

According to Wilkinson, ‘in the original plaster and in the bronze casts each of the forms may be turned and positioned in various combinations’.13 This suggests that Moore allowed for an element of variation in the work: the sequence of the motives could be swapped and their orientation could be changed. Although minimal, this variation is evident between the Tate cast and the version held in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, in which the middle motive has been swivelled slightly clockwise. Moore first explored the possibility of using moving parts within a sculpture while he was carving Screen for the Time-Life Building in Bond Street in 1952–3, which comprised four geometric stone arrangements that Moore wanted to be able to turn on a central pivot, but safety concerns prevented his scheme from being carried out.

Origins and interpretation

In his 1981 catalogue entry for Three Motives Against Wall No.2, which was based on conversations he had had with Moore in December 1980, the Tate researcher Richard Calvocoressi accounted for the origins of the sculpture:

his interest in making relief sculpture, which had lain dormant since his work on the London Underground Building in the late Twenties, was reawakened when he was commissioned to design a large wall relief in brick for the façade of the Bouwcentrum in Rotterdam, unveiled in December 1955. This project led to the idea of releasing the forms from their incorporation in the fabric of the wall so that they become free-standing, as in T.2281 [Three Motives Against Wall No.2].14

Henry Moore

Unesco Reclining Figure 1957–8

Travertine marble

Unesco, Paris

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Unesco Reclining Figure 1957–8

Unesco, Paris

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In the case of the UNESCO commission he had to invent both concept and image, some symbol that had relevance to the educational and scientific aims of the institution established by the United Nations. There are several illustrations in this volume which show the artist struggling with the problem ... Some of these [preparatory] maquettes ... also illustrate the subsidiary but still very harassing problem of having to accommodate the piece of sculpture against a background of busy fenestration which tended to destroy its outlines and mass. The sculptor played with the possibility of interposing his own wall between the figure and the building, and though this solution was abandoned, it led to a theme, ‘the wall’, which the sculptor was to exploit later.18

Henry Moore

Maquette for Girl Seated Against Square Wall 1957

Bronze and marble

270 x 215 x 215 mm

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Maquette for Girl Seated Against Square Wall 1957

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

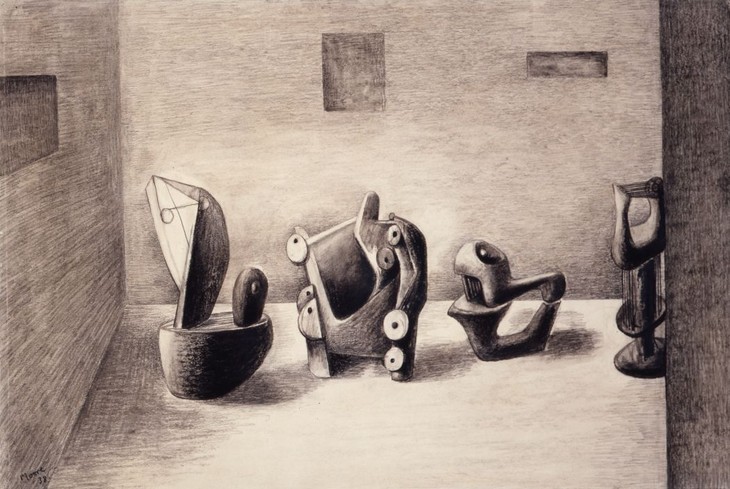

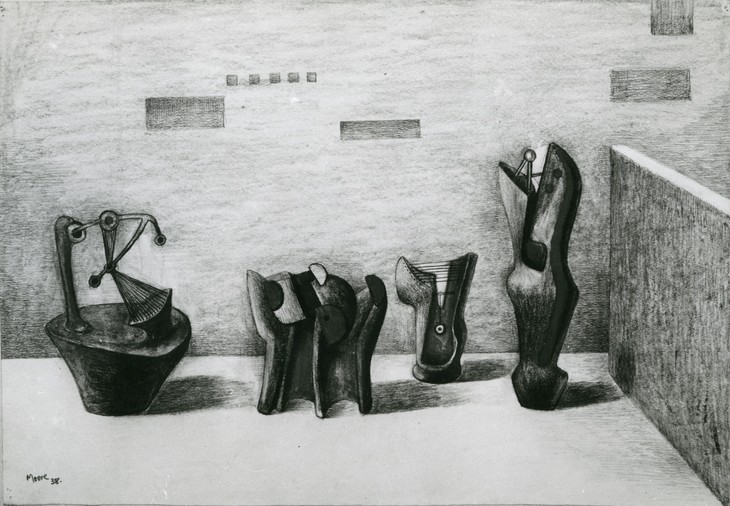

Alan Wilkinson noted in 1987 that although Moore did not incorporate imprinted walls in his sculptures until the late 1950s, the ‘rectangular slotted walls first appear in the drawings as early as 1936 as a background for sculptural ideas. In some of the drawings diagonal walls lead into the picture space and with the background wall create a claustrophobic, cell-like setting, as in Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting of 1938’ (fig.12).19 The enclosed character of the spaces depicted in Moore’s drawings of the 1930s had previously been commented upon by the psychologist Erich Neumann in his book The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, published in 1959. Neumann suggested that:

the placing of the Ideas for Sculpture [fig.13] in a ‘setting’ animates these mysterious beings to an extraordinary degree and makes them even more uncanny. The setting ... [may] be taken as a symbol of our civilisation, or our urban, walled-in existence, and of the restrictedness of our consciousness, which has lost touch with nature and life. It is a prison life that the setting shows us, and our estrangement from nature, our imprisonment in a world of walls, is revealed in the eerie loneliness that surrounds each of the figures trapped in this terrifying milieu.20

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting 1938

Charcoal, chalk and ink wash on paper

381 x 557 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting 1938

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting 1938

Chalk, wash, pen and ink on paper

381 x 559 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting 1938

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Neumann went on to discuss Moore’s uncanny architectural spaces in relation to the work of the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978), whose work was admired by surrealist artists including René Magritte and Paul Nash. De Chirico’s paintings frequently depict enigmatic town squares, shadowy architectural facades and claustrophobic urban environments that create a tense and menacing atmosphere. In 1965 Read concurred stating that Three Motives Against Wall No.2, alongside the ‘Upright Motives’ series (Tate T02274–T02276) and Three Part Object 1960 (Tate T02285), was ‘as powerful and sinister as anything yet created by the sculptor’.21

In 1973 the critic John Russell sought to account for the indeterminate, amorphous forms of the three motives, arguing that they represented qualities that could not be expressed with reference to human experience. For Russell, in Three Motives Against Wall No.2

the three anonymous, unnameable forms are just there: no explanation comes to hand. Anyone who has watched a space-fiction serial will know that the most difficult thing is to carry conviction with an invented form that does not somewhere rely upon human or mechanical affinities. Moore has achieved, here, what the novelist and scenarist fall down on: the invention of forms which impress themselves immediately as definable personalities and yet do not appeal to already existing categories of experience.22

Moving away from these more cerebral interpretations, writing about the middle motive in 2006 Wilkinson reflected that ‘for many years it reminded me somewhat of a head of a hippopotamus, until a more perceptive young schoolboy gleefully exclaimed: “Look Mummy, Snoopy from Peanuts”’.23

The Henry Moore Gift

Henry Moore presented Three Motives Against Wall No.2 to the Tate Gallery in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift. The Gift comprised thirty-six sculptures in bronze, marble and plaster and was exhibited in its entirety alongside Tate’s existing collection of Moore’s work in an exhibition celebrating the artist’s eightieth birthday, which opened in June 1978. A press release was duly prepared announcing that ‘The group [of sculptures] is the most substantial gift of works ever given to the Tate by an artist during his lifetime’.24 Three Motives Against Wall No.2 was displayed in the exhibition next to Relief No.1 1959 (Tate T02284). The exhibition was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.25 At the close of the exhibition in late August 1978 the Director of Tate Norman Reid reflected in a letter to Moore’s daughter that although he was sad to see the exhibition come to an end ‘we have the consolation of the splendid group of sculptures which Henry has presented to the nation’.26

Other casts of Three Motives Against Wall No.2 are held in the collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, The Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green, and in private collections. The original plaster version of the sculpture is in the Moore Collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto.

Alice Correia

March 2013

Notes

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.215.

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.184.

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Three Motives against Wall No.2’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.258.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, p.18, transcript of Third Programme, broadcast BBC Radio, 14 July 1963, Tate Archive TGA 200816. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

Art Bronze Foundry, London, casting bill to Henry Moore, 7 June 1962, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

[Richard Calvocoressi], ‘T.2281, Three Motives Against Wall No.2’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.126.

See, for example, Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, pp.212–19, and Julian Stallabrass, ‘Three Motives against Wall No.1’, in Mitchinson 2006, pp.256–8.

Anita Feldman Bennet, ‘Figures in Architectural Settings – the UNESCO Experiments’ in David Mitchinson (ed.), Henry Moore and the Challenge of Architecture, Much Hadham 2005, p.22.

Henry Moore cited in David Sylvester (ed.), Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1951, p.4.

Herbert Read, ‘Introduction’, in Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, p.6.

Related essays

- Henry Moore and the Values of Business Alex J. Taylor

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Three Motives Against Wall No.2 1959, cast 1962 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www