Rene Matić

Chiddy Doing Rene’s Hair

(2019, printed 2021)

Tate

What do we really mean when we use the words diaspora or diasporic? In this article, we will explore the origins of the term diaspora, its changing meanings over the course of time, the thinkers and writers who have contributed to thought around it and the artists who can help us begin to understand the many and varied aspects of it.

ORIGINS, SCATTERING

The origin of the term diaspora goes back to an Ancient Greek word, διασπείρω, meaning ‘to scatter’. It is most widely used today to describe people who have migrated from one part of the world to another, or those who are descended from people who have.

Some of the most prominent and earliest usages of the word refer to historic groups such as the exile of Jewish people from the Kingdom of Judah (an Israelite Kingdom of the Southern Levant), the Athenians’ ruin of Aegina and the expulsion of its people, those forced to migrate as a result of the Irish famine, Armenians fleeing genocide after World War I and the enslaved African people who were forcibly transported to the Americas and elsewhere as part of the transatlantic slave trade.

In recent years, the term has expanded exponentially and as Armenian-American scholar and pioneer of diaspora studies, Khachig Tölölyan wrote in 1991, ‘the term that once described Jewish, Greek, and Armenian dispersion now shares meanings with a larger semantic domain that includes words like immigrant, expatriate, refugee, guestworker, exile community, overseas community, ethnic community.’ Over time, the term and what it signifies for different groups and individuals has evolved meaning that now more than ever, diaspora is a complicated thing to break down or sum up. The diasporic experience of ancient times has been intercut with modern, complex positionalities around race, nation, religion, sex, gender, sexuality, politics, class, tradition and culture. What do we really mean when we use the words diaspora or diasporic?

This essay will take a series of artworks, mostly from the Tate collection, as starting points to explore the multifaceted nature of the diasporic experience. There are many threads which make up the rich tapestry of the diaspora and when using the term indiscriminately, we run the risk of obscuring some of the important aspects the term entails. Of course, the fact that it is such a complex thing means that attempts to pin down the meaning of the word to a singular definition would be reductive and as such, this article is not intended to be exhaustive, but rather to function as an introduction to the multi-layered and ever evolving nature of diaspora.

As discussed briefly in the first paragraph, some of the earliest recorded diasporic groups came as a result of exile, forced migration or those seeking refuge having been subjected to displacement. Lubaina Himid’s work, Drowned Orchard: Secret Boatyard 2014 comprises sixteen paintings on long wooden planks, lined up vertically at increasing angles against the gallery wall. The artwork was partially inspired by her personal experience as a Black woman travelling in South Korea, where she was repeatedly asked by various members of the public, ‘where are you really from?’ when she gave her nationality as British. Himid has described her encounter with one person: ‘I answered with a reply I’ve not had to use since the early 1980s in Britain – Zanzibar. This was all the woman needed, she seemed to want to know that I came from a place that Black people should come from.’ (Lubaina Himid, email correspondence with Tate curator Laura Castagnini, 25 April 2018.) Water is central to the imagery painted onto the planks, with ships and boats displayed next to a painting of a jug of flowing water. The jug is something which Himid has used throughout her work in memorial to the Zong massacre of 1781 in which 133 enslaved African people were thrown overboard to drown. Maritime flags also feature with coded messages such as ‘You should stop, I have something important to communicate’ and ‘Man overboard’. Bringing these images, symbols and codes together draws connections between the violence of the transatlantic slavery whilst also potentially referencing dangerous border crossings made out of desperation today.

Of course, the repercussions of forced relocation echo through the generations for diaspora communities and have relevance in a way that doesn’t necessarily conform to a linear concept of time. The writer Saidiya Hartman has written about what she refers to as ‘the afterlife of slavery’ in order to describe ‘the skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment’ which continue to disproportionately affect life for Black people. Through her texts such as Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, 2007, and Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval, 2019, Hartman bridges the gaps and fills them in where archives of trans-Atlantic slavery are desperately lacking in the voices of enslaved women.

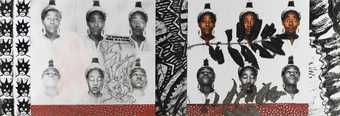

From Tarzan to Rambo: English Born ‘Native’ Considers her Relationship to the Constructed/Self Image and her Roots in Reconstruction is a photo-based work with acrylic, ball-point pen, crayon and felt-tip pen in which the artist, Sonia Boyce examines the effect of the historical dispersion of Black, African peoples across the globe through slavery and colonisation. The artist herself is the 'English born Native' mentioned in the title. The concept for the work developed out of a desire to put into dialogue, her own self-image as a Black person, and more specifically, as a Black woman, with the stereotypical image perpetuated by Old Hollywood and other predominantly white controlled media of Black people as brutes or clowns. The works also demonstrates how a sense of diaspora consciousness can be constituted both negatively and positively.

CONNECTIONS AND RECOLLECTIONS

The horrendous nature of many of these early examples of involuntary movement mean that diasporic consciousness holds for many communities, the pain of displacement or dispersal. However, through these shared experiences, diasporic communities often find solace in community. That may be within communities of the same faith or from the same country of origin, but also happens in groups from different diasporic communities, coming together and bonding through a shared diasporic sensibility. Collective memory, song, stories, faith and rituals are just some of the many ways that this sensibility is expressed, and solace is sought.

Khadija Saye

Nak Bejjen

(2017)

Tate

Nak Bejjen, meaning cow horn, is a photograph from Khadija Saye’s series Dwelling: in this space we breathe 2017. The series explores Saye’s interest in and understanding of spirituality and the way in which trauma is embodied in the Black experience. The works were created in 2017 with the assistance of artist Almudena Romero, and depict Saye as the subject of a series of portraits in which she enacts invented rituals using sacred objects from her parents’ country of origin, Gambia, whilst clothed in outfits belonging to her mother. Having been raised in a dual faith household with a Muslim father and Christian mother, Saye was conscious of the role which faith can play in determining identity. Saye discussed how significant religion often is for members of diasporas attempting to maintain connections to homes left behind. The work calls into question the rituals or objects that we turn to for solace in life’s most challenging moments. The process of producing wet plate collodion tintypes is easily affected by elements outside the artist’s control; in order to create the work, Saye surrendered herself to a higher power. In a disposable age, Saye’s use of this photographic technique reminds us to dwell in the moment and foster our inner connections.

Ibrahim El-Salahi

Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I

(1961–5)

Tate

Ibrahim El-Salahi studied painting in Khartoum, Sudan, in the late 1940s before completing his studies in London. When he returned to Sudan in 1957 it was a newly independent country in the middle of a civil war. In the painting, Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I, ghostly figures emerge and interweave. While the heads of the figures recall African masks, the artist has also suggested that the ‘elongated, black-eyed, glittering facial shapes might represent the veils our mothers and grandmothers used to wear in public, or the faces of the drummers and tambourine players I had seen circling wildly during funeral ceremonies and chants in praise of Allah’ (Ibrahim El-Salahi, ‘The Artist in His Own Words’, in Hassan 2013, p.84).

In this work El-Salahi, who frequently draws upon childhood memories and visions experienced during meditation, captures moments when memory and dreams, past and present collide. In his words, he seeks to ‘register and describe what I perceive through the senses while remaining tightly bound to an elusive, indecipherable, metaphysical essence’ (El-Salahi, ‘The Artist in His Own Words’, in Hassan 2013, p.89).

SYNCOPATED TEMPORALITY

In the last few works, we have seen examples of artists for whom time is not necessarily something linear. It is interesting to think about the idea of diaspora not just as a term to be neatly defined but as a phenomenon which can bring about a certain kind of diasporic consciousness through which members of diaspora communities can make sense of the world in which they find themselves.

Theorist and writer, Paul Gilroy has said that tradition in the context of diaspora, ‘can be seen to be a process rather than an end and is used neither to identify a lost past nor to name a culture of compensation that would restore access to it. Here, too, it does not stand in opposition to modernity nor should it conjure up wholesome, pastoral images of Africa that can be contrasted with the corrosive, aphasic power of the post-slave history of the Americas and the extended Caribbean. Tradition can now become a way of conceptualizing the fragile communicative relationships across time and space that are the basis not of diaspora identities but of diaspora identifications. Reformulated thus, it points not to a common content for diaspora cultures but to evasive qualities that make inter-cultural, trans-national diaspora conversations between them possible.’ (Gilroy 1993a:276)

In this way, it is arguable that we find the real meaning of diaspora in the acts of relation and networks of connected histories and this realm in which time moves in echos backwards and forwards.

Gilroy is one of the world’s foremost theorists of race and racism and is a scholar and historian of the music of the Black Atlantic diaspora. He has described a particular ‘diaspora temporality’ which does not conform to western, modernist ideas of linear trajectories of progression and instead reveals a ‘syncopated temporality-a different rhythm of living and being’ (Gilroy 1993a:281). Gilroy cites Ralph Ellison: ‘Invisibility, let me explain, gives one a slightly different sense of time, you’re never quite on the beat. Sometimes you're ahead and sometimes behind. Instead of the swift and imperceptible flowing of time, you are aware of its nodes, those points where time stands still or from which it leaps ahead. And you slip into the breaks and look around’. (Gilroy 1993a:281)

One of the works Gilroy has extensively discussed which provides an example of ‘diaspora temporality’ is Handsworth Songs, 1986 by Black Audio Film Collective (John Akomfrah; Reece Auguiste; Edward George; Lina Gopaul; Avril Johnson; David Lawson and Trevor Mathison).

Black Audio Film Collective, still from Handsworth Songs, 1986. Courtesy of Black Audio Film Collective and LUX, London

Handsworth Songs is a 59 minute long, richly layered documentary film representing the hopes and aspirations of Black British people in light of the civil unrest of the 1980s. The mention of Handsworth in the title, is a reference to an area of Birmingham where uprisings took place in September 1985. The film deploys a montage technique with a shifting narrative that attempts to poeticise certain moments. It functions as a kind of experimental visual essay with a complex mix of archive material, footage shot by the Black Audio Film Collective and sound designed by the Collective which draws upon dub, voice loops and electronics. It was first commissioned by Channel 4 but, in the relevance of its presentation of life for diasporic communities in the hostile political environment of the UK has endured and it was shown at Tate Modern in 2011 in the wake of the fatal shooting of Mark Duggan by police officers and again, at Lisson Gallery in 2020 after the death of George Floyd at the hands of US police officers.

John AkomfrahThe Unfinished Conversation 2012© John Akomfrah / Smoking Dogs Films

John Akomfrah was one of the founders of the Black Audio Film Collective and in 1998, together with Lina Gopaul and David Lawson, his long-term producing partners, he co-founded Smoking Dogs Films. In 2012, they made the work The Unfinished Conversation, 2012, which looks at the multi-layered and ever-evolving subject of identity through an exploration of the memories and archives of the acclaimed cultural theorist and sociologist Stuart Hall. In his book, Familiar Stranger, Hall wrote:

The term diasporic both responds to, and goes beyond, the reductive boundaries of what has come to be known as ‘identity politics’. Identities are in this process indeed reconstructed, transformed, problematized, pluralized, mobilized, set in antagonistic positions towards one another. The diasporic challenges the idea of whole, integral, traditionally unchanging cultural identities. No identities survive the diasporic process intact and unchanged, or maintain their connections with the past undisturbed.

Stuart Hall

Akomfrah has spoken widely about the great influence Stuart Hall had on him over the course of his career and the film was the result of more than three years of research and production with Akomfrah working closely with Hall. The film is narrated in a non-linear format and unfolds over three screens, bringing up a variety of disparate footage simultaneously. This process examines the nature of the visual as triggered across an individual’s memory. Extracted images from news footage of the 1960s, alongside Hall’s personal home videos and photographs, are presented to merge the past, present and future. Akomfrah weaves issues of cultural identity within the film using a poetic soundscape, overlaying archive footage of Hall with a soundtrack made up of jazz and gospel music and readings from a wide range of authors, including William Blake, Charles Dickens, Virginia Woolf, and Mervyn Peake.

In The Unfinished Conversation, Hall discusses his discovery of personal and ethnic identity. Born in Kingston, Jamaica into a middle-class family where he was the ‘darkest’ member, he quickly found that this had an immense effect on his upbringing in Jamaica. He arrived in Britain as a young man in 1951, graduated from Oxford University and went on to become one of the founding figures of British Cultural Studies and a strong voice on the journal New Left Review, alongside other intellectuals such as E.P. Thompson and Raymond Williams. Akomfrah’s film, which focuses on Hall’s formative years of the 1950s and 1960s, also encompasses wider international political changes, for example the Soviet invasion of Hungary, the Vietnam war, or uprisings in Britain. Akomfrah has explained that the use of different footage and multiple screens also portrays how identity is formed as part of a collision of history, culture, and politics. In The Unfinished Conversation identity is presented as a conjunction of the outside and the inside, where individual subjectivities are formed in both real and fictive spaces.

CONTRAPUNTAL AWARENESS

Many different theorists and writers have explored this concept of identity (diasporic or otherwise) as multi-layered and ever evolving. In 1990, Palestinian-American academic, political activist, and literary critic, Edward Said used the term ‘contrapuntal’ to reflect on a positive aspect of displacement from one’s place of birth or ancestral origin: ‘Seeing "the entire world as a foreign land" makes possible originality of vision. Most people are principally aware of one culture, one setting, one home; exiles are aware of at least two, and this plurality of vision gives rise to an awareness of simultaneous dimensions, an awareness that - to borrow a phrase from music - is contrapuntal.... For an exile, habits of life, expression or activity in the new environment inevitably occur against the memory of these things in another environment. Both the new and the old environments are vivid, actual, occurring together contrapuntally.’

In 1903, sociologist, historian and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist, W. E. B. Du Bois published The Souls of Black Folk in which he introduced what he described as ‘double consciousness’ to describe the experience of experienced of ‘always looking at one's self through the eyes' of a racist, white society’ and ‘measuring oneself by the means of a nation that looked back in contempt'.

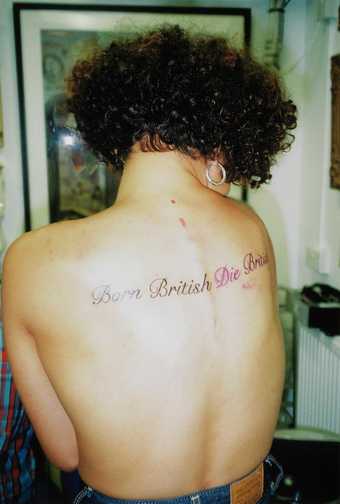

Rene Matić

Rene at New Wave Tattoo

(2020, printed 2021)

Tate

Working across painting, sculpture, film, photography and textile, Rene Matić's practice employs an often autobiographical take on the infinity possibility and scope of Blackness through their own personal experiences as a queer, Black womxn. Their work often explores the skinhead movement and its origins as a multicultural meeting of West Indian and white working-class culture. In this photograph, the artist is having the phrase, 'Born British, Die British’ tattooed onto their back. This is a phrase which is often used to signify the fact that someone is announcing their investment in the idea of a right wing, white version of Britishness. The tattoo artist, Lal Hardy, has been tattooing punks and skinheads in Britain since 1979, the year that Thatcher became Prime Minister. Here, a 23 year old mixed-race, non-binary femme has their body indelibly marked by a white, middle-aged man with a powerful and controversial statement in an act of reclamation and subversion, reconciling the duality of their British identity with their identity as a member of the Black diaspora.

Zineb Sedira

Mother Tongue

(2002)

Tate

This diasporic reconciliation of cultures often involves more than two countries or languages. In Zineb Sedira’s 2002 video work, Mother Tongue, the artist, her mother and her daughter try to exchange childhood memories in their native languages: French, Arabic and English. Sedira was born in Paris to Algerian parents, and moved to London to study art, where her daughter was born. The work reflects on storytelling as a way to preserve cultural identity across generations. It underscores the difficulty of maintaining a shared heritage across national and linguistic divides and the complexity of diasporic identity.

REMAINING, THRIVING

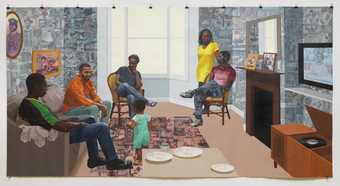

Njideka Akunyili Crosby

Remain, Thriving

(2018)

Tate

© Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Commissioned by Art on the Underground.

This large, almost two by four metre painting with collage elements depicts an imagined front room in which a relaxed domestic scene unfolds. The family photos, sideboard record player, doily arm rest cover and photo-collaged images on the walls reminiscent of the bold wallpaper often found in Afro-Caribbean households all hint at a living room belonging to a family which is part of the Black British Diaspora. The gathering includes people of a similar age to the grandchildren and great grandchildren of the Windrush generation (the migrants who arrived in Britain on the SS Windrush after 1948 from the Caribbean). The painting was the first in a series of new works commissioned by Art on the Underground for Brixton Station in south London. The artist spent time speaking to members of the local community, as well as archivists at the Black Cultural Archives and the Lambeth Archives. The collaged elements of the painting include archival images of local landmarks, as well as celebrated figures such as Jamaican born poet Linton Kwesi Johnson and community leader Olive Morris. The painting’s hopeful title refers to the diasporic communities who, despite political and economic hardships, such as the news reports of the Windrush scandal unfolding on the living room television, have remained vital to Brixton’s social fabric.

The construction of diasporic identity, indeed all identities, as the breadth of artists discussed here have shown, provides the opportunity for each person to build a ‘self’ which takes into account every thread of their human fibre; every nuance of their lived experiences, memories, aspirations and inherited histories work in tandem to form an individual. There is enormous power in that open-ended sense of agency over the self.

Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor.

About AÏCHA MEHREZ

Aïcha Mehrez is a curator, writer and doctoral researcher with Tate and the University of Leicester. Her curatorial practice reflects upon ways in which curatorial methodologies centred in care can make museums and galleries spaces of collective healing and discussion where a spirit of kinship is fostered. Her PhD focusses on legacies of slavery and empire in the art museum. Most recently, she curated Sixty Years: The Unfinished Conversation at Tate Britain which looked at diasporic identity in Britain through the Tate collection.