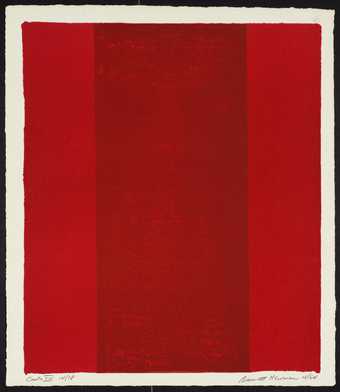

Whatever else it may ask of us, a painting demands that we view it from a proper distance. A Chardin still life draws us close, and we move back for a view of water lilies set afloat by Claude Monet on mural-sized stretches of canvas. Nine feet high and a touch over 20 feet wide, Anna’s Light 1968, by Barnett Newman, is larger than the largest of the Monet Water Lilies in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Confronted by this wall-sized expanse of red, viewers seek the opposite wall. Yet this is not what Newman wanted. Even after he became a monument of post-war American art – a triumph now celebrated with a retrospective at Tate Modern – audiences rarely gave him what he wanted.

Bafflement tinged by derision greeted his first solo exhibition, in 1950. What was one to make of these immense rectangles of colour split, here and there, by vertical stripes? Even Newman’s friends among New York’s artists were stymied. Viewers, he concluded, needed guidance. For his second show, the following year, he typed out a notice and pinned it to the gallery wall: ‘There is a tendency to look at large pictures from a distance. The large pictures in this exhibition are intended to be seen from a short distance.’ Newman wants us to immerse ourselves in his pictures. We are to stand so close that the canvas reaches beyond the edges of our peripheral vision. Painters count as radical if they manage to change the look of painting. Newman wanted to change the way we look.

Over the decades, audiences have learned to luxuriate in the expansive luminosity of Newman’s canvases, and to savour his shifts in emotional key, from sombre to joyous to disconcertingly calm. With the pale blue and chocolatey brown of Uriel 1955, Newman finds the visual counterpart of a landscape silenced by fog. The Stations of the Cross 1958–66, a series of 14 canvases, evokes the stages of spiritual extremity – but only if you are willing to take the cues offered by the artist’s titles and commentary.

Understandably enough, some resist, bridling at the sight of large, nearly monochrome canvases purporting to be serious works of art. Newman is by far the most frequently vandalised painter of modern times – an odd fate for the most genial artist of his generation. Everyone liked Barney, as he was known to close friends and casual acquaintances alike. When Newman died, in 1970, at the age of 65, notables were canvassed for reminiscences. ‘I think Barney went to more parties than I did,’ said Andy Warhol. ‘He always asked me how I was. He was so kind.’ At an age when an established artist might very well withdraw from circulation, in the hope of becoming an éminence grise, Newman still made the rounds of gallery openings. And, astonishingly enough, he was willing to look at younger artists’ work. In Manhattan, one still runs across painters – veterans now – who remember with fondness the early encouragement they received from a figure who had already acquired the aura of history.

Newman tempered his mercies with a quick and not always kindly wit. In letters, panel discussions, and impromptu debates, he made the case for his art with a fencing master’s flair. In essays and manifestos, he rewrote art history to the measure of his boundless ambitions. Perhaps only Ralph Waldo Emerson, writing more than a century earlier, insisted more persuasively on the need for an aesthetic of American optimism. In ‘The Sublime Is Now’, an essay composed in 1948, Newman declared his faith that ‘here in America, some of us, free from the weight of European culture…are asserting man’s desire for the exalted, for a… relationship to the absolute emotions.’ Abstract painting was not to be an exercise in design. It was to provide a vision of ultimate things.

The erudition and indefatigable volubility of Newman the theoretician did much to convince the New York art world, early on, that Newman the artist could be safely overlooked. This was an error, yet one feels a certain sympathy for Newman’s detractors. The New York of the 1950s was dominated by the raucous subtleties of Willem de Kooning’s Abstract Expressionism. That was painting: complex, daring, alive to the precedents of the Parisian avant-garde yet grounded in a solid academic tradition.

Though Jackson Pollock never bothered with even the rudiments of traditional technique, he made up for this lack with the finesse of his dripping and pouring. This too was painting: energetic, strangely beautiful and ultimately more influential than de Kooning’s. By contrast, Newman had the look of an amateur messing about with masking tape and a house painter’s brushes – though Pollock, a close friend, saw right away the affinities between their paintings. By the end of the 1950s, many had learned to see what Pollock had seen. Quickly, Newman assumed the place he still holds in the first rank of post-war American painters.

During the next decade, his position was made unassailable by the admiration of Frank Stella, Donald Judd, Carl Andre and other young artists with no patience for painterly histrionics á la de Kooning. In Newman’s ruler-straight edges and just barely inflected surfaces these Minimalists found warrants for the impersonality that earned them their name. The seasons of the art world move quickly, and Minimalism soon became a period style marooned in the 1960s. Nonetheless, its hard-edged, hands-off austerity has been leaving its mark on new art for nearly four decades. Thus genealogies emerge, reaching back from the latest revival of the Minimalist object, to the Minimalists themselves, and farther still, to Newman the progenitor.

A patriarch of American modernism, Newman received the tribute of parody from such irony-mongers of the 1980s as Phillip Taafe and Peter Halley. Of course they got him wrong – knowingly so – for they treated him less as an artist than as a sort of George Washington figure, the founding father of an officially approved sensibility. It now appears that the Minimalists, too, misread Newman. Ideally, a work of Minimalist art is no more or less than what it is: an object enclosed by the self-evident facts of its simplified form. As the author of ‘The Sublime Is Now’, a paean to unbounded energies of the eye and spirit, Newman rejected enclosures of every kind.

Still, the Minimalists had good reason to see him as their most immediate ancestor. Their principal devices were right angles, flat planes, symmetr y, and repetition. Newman’s mature work is rigorously geometric and un-deniably repetitious: time and again, he punctuates a field of colour with vertical stripes, which the artist called ‘zips’. Only rarely, however, is there symmetry in the pattern of their placement. With unpredictable syncopations, the zips establish intervals that carry the eye – and imagination – past the boundaries of the frame. Deploying the sparsest of means, Newman gives us intimations of the infinite.

These are easily missed, especially if we take up the wrong vantage point. From too far back, even Anna’s Light and Vir Heroicus Sublimis 1950–1, with their grandly un-furling fields of red, have the look of enclosed compositions. It is better to get close, as recommended, and give vision a chance to immerse itself in the still uncharted regions of Newman’s sublime. Naturally, our wised-up art world tends to dismiss out of hand his rhetoric of the exalted and the absolute. The sublime was then, maybe, but now the artist’s game is the politics of style – or the stylishness of politics – and Newman owes his present pre-eminence to the monumental elegance of his outsized canvases.

They are indeed monumental and undeniably elegant, so there is a strong temptation to see Anna’s Light, for instance, as just one of many big, beautiful objects in Newman’s oeuvre – as if this canvas were an abstract painter’s variation on one of those big, beautiful Amazons Helmut Newton likes to photograph. There is, of course, no reason to underplay the luscious sensuality of Newman’s livelier pictures. Still, our pleasure in his art doesn’t require us to ignore his writings or his titles, even at their most grandiose. Vir Heroicus Sublimis – Man, Heroic and Sublime – is not just a flourish of empty words.

‘The first man was an artist,’ wrote Newman in 1947, going on to argue that the point of being an artist now is to find one’s way back to humanity’s primordial possibilities. There is more than a touch of American millenarianism here, a faith in the redemptive powers of the New World spirit. Discounting all that, we’re left with a sense of Newman’s down-to-earth confidence in himself. Art can be renewed, and he was just the man to renew it, because he felt in his bones that history is not a closed system of preset outcomes. If art is renewable, so is society. So are politics and the marketplace. Possibilities are endless, Newman believed, not only for his art but for those who let themselves be infected by his optimism.

About the artist

Born in 1905 in New York, the son of Polish immigrants, Barnett Newman studied and taught art in his spare time for many years while running his father’s clothing business. In 1933 he ran for mayor of New York, advocating public funding for art and controls on pollution. In the early 1940s he gave up painting, destroyed most of his early work and wrote The Plasmic Image, a treatise on the aesthetic and philosophical aims of modern art. His full-time art career did not start until 1950, with his first solo exhibition at New York’s Betty Parsons Gallery. He died in 1970.

This article was originally published in Tate Magazine issue 1.