Sublime Effect: James Thornhill’s A Ceiling and Wall Decoration and The Apotheosis of Romulus: Sketch for a Ceiling Decoration and Peter Paul Rubens’s Apotheosis of James I

Lydia Hamlett

The first known treatise on the sublime, Peri Hypsous, thought to be written in the 1st century AD by the Ancient Greek writer known as the Pseudo-Longinus, was concerned above all with composition in language and oratorical effect on audiences. This could be achieved in various ways, including the choice of vocabulary, subject matter, structure and style. These principles were applied by Pseudo-Longinus to poetry and rhetoric (in this case, public speaking), but in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries they were extended to discussions on art, just as other classical rhetorical rules had been in the intervening years. The ‘rediscovery’ of Pseudo-Longinus’s treatise and its first publication in the mid-sixteenth century came at a time when artists and writers emphasised the effect and experience of the composition on the spectator above all else. The subjects – for example, histories or portraits – could be morally elevating, but the persuasive compositional devices of baroque art could also be uplifting for the viewer. These devices included exaggerated perspective, an unsettling transition between the actual and the illusionistic, colour for effect, and the inclusion of an overwhelming numbers of people or objects or wide expanses of open space – all of these things were intended to have a physical and emotional effect on the spectator. The genre where this experience is most evident is so-called ‘decorative history painting’, the illusionistic wall landscapes and ceiling skies that were found in grand domestic interiors in Britain, the extension of a long-established continental practice which saw art of this type used most often to persuade the viewer of a political or religious truth. Indeed, the painted ceiling could almost be interpreted as the literal embodiment of the sublime – meaning ‘under’ or ‘up to’ the lintel in architecture – and the answer to Pseudo-Longinus’s question, ‘how should men reach the gods?’.

Sir James Thornhill 1675 or 76–1734

A Ceiling and Wall Decoration circa 1715–25

Pencil, pen and ink and watercolour on paper

support: 311 x 391 mm; frame: 547 x 619 x 25 mm

Tate T08143

Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996

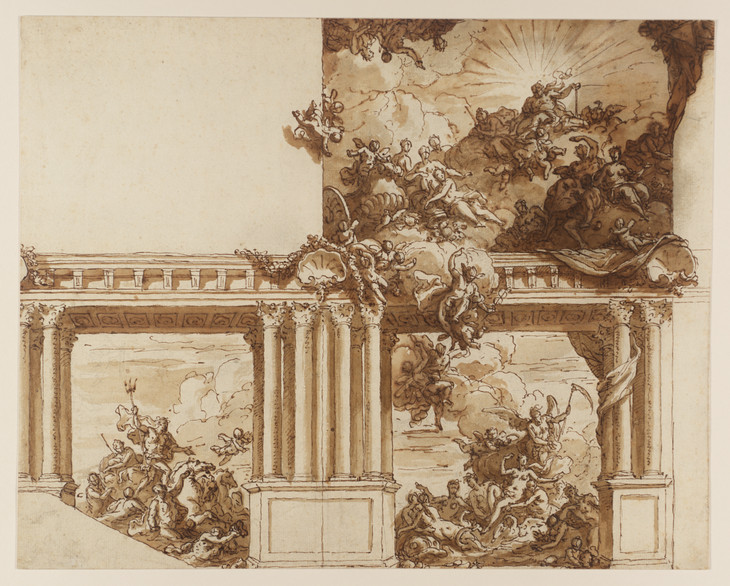

Fig.1

Sir James Thornhill

A Ceiling and Wall Decoration circa 1715–25

Tate T08143

James Thornhill’s sketch for A Ceiling and Wall Decorationdates from c.1715–25 (Tate T08143, fig.1) and is possibly a design for the decoration of the staircase at Cannons, the now destroyed palace of James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, near Stanmore in Middlesex.1 It would have formed part of a type of decorative scheme that was becoming increasingly fashionable for monumental interiors in late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Britain. Many of these were private commissions for the houses of the aristocracy but there were also more public examples, such as the ceiling of the Painted Hall at Greenwich Hospital. The effect on viewers of such decorations was intended to inspire awe, and indeed the writer Richard Steele, who visited the Painted Hall in 1715, wrote that he was lost for words on seeing it, claiming that it was not ‘in the Power of Words to raise too great an Idea of the Work ... The whole raises in the Spectator the most lively Images of Glory and Victory, and cannot be beheld without much Passion and Emotion.’2 This recalls the inability to describe something which is a significant part of the sublime impact or ‘affect’ which was discussed by theorists including the French writer Nicolas Boileau and the English artist and theorist Jonathan Richardson.

The design and decoration of the country house of Cannons was intended to stimulate a reaction of this type; to display Chandos’s wealth, political power and connoisseurship, the house was lavishly decorated both inside and out, and strangers and associates alike travelled far and wide to see it. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that it succeeded in making a powerful impression on visitors. When the writer Daniel Defoe visited the house in 1725 he wrote of being so affected by the sight of it that he could not write down his feelings and recommended that one experience it for oneself.3 The painted interiors were designed in parallel with the architecture and were equally impressive. The sketch in Tate’s collection (fig.1) is a design for a grand staircase and shows mythological scenes in a painted architectural setting. The staircase ceiling (in the compartment to the upper right) shows an assembly of gods in the heavens, some of whom – including Mercury with his winged helmet – spill out of the sky and on to the architectural frame. On the staircase walls are two sea scenes: the Birth of Venus (in the lower right compartment), and the sea god Neptune in his chariot (in the lower left).

Sir Peter Paul Rubens 1577–1640

The Apotheosis of James I and Other Studies: Multiple Sketch for the Banqueting House Ceiling, Whitehall circa 1628–30

Oil on panel

support: 947 x 630 mm

Tate T12919

Purchased with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, Tate Members, the Art Fund in memory of Sir Oliver Millar (with a contribution from the Wolfson Foundation) Viscount and Viscountess Hampden and Family, Monument Trust, Manny and Brigitta Davidson and the Family, and other donors 2008

Fig.2

Sir Peter Paul Rubens

The Apotheosis of James I and Other Studies: Multiple Sketch for the Banqueting House Ceiling, Whitehall circa 1628–30

Tate T12919

Sir James Thornhill 1675 or 76–1734

The Apotheosis of Romulus: Sketch for a Ceiling Decoration, Possibly for Hewell Grange, Worcestershire circa 1710

Oil on canvas

support: 457 x 521 mm

Tate N06200

Purchased 1953

Fig.3

Sir James Thornhill

The Apotheosis of Romulus: Sketch for a Ceiling Decoration, Possibly for Hewell Grange, Worcestershire circa 1710

Tate N06200

Pseudo-Longinus’s concept of the sublime constantly referred to humans reaching up to be as near to the divine as possible. The ancient idea of apotheosis, or deification, was that the souls of monarchs and great humans could traverse up to heaven and actually become gods. This was explored through myths about mortals, such as Hercules, as well as real-life heroes who were deified, such as Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar. In Baroque Europe the ‘apotheosis’ once again became prevalent in political allegory, but also in art as it was visualised in many ceiling paintings. Peter Paul Rubens depicted the Apotheosis of James I in the ceiling of the Banqueting House at Whitehall in London. The final painting is still in its original location today. A sketch for it from c.1628–30 is in Tate’s collection (T12919, fig.2). The painting was commissioned by Charles I and depicts his father being carried into the heavens. An eagle can be seen underneath the orb upon which the king is lifted, symbolising the eagle released in ancient deification ceremonies to signify the soul rising up to heaven, and which was included on the title page to the first version of Peri Hypsous published in Britain in 1636. An eagle can also be seen next to Zeus, king of the gods (for whom it was also an attribute), in another sketch for a ceiling showing a deification, Thornhill’s The Apotheosis of Romulus c.1710 (Tate N06200, fig.3). The century which passed between these two artworks saw many nobles commission apotheoses to be painted on ceilings in their country houses, either of themselves or of mythical figures who they hoped to connect themselves with allegorically. The overwhelming impact of these works was intended as a kind of sublime effect.

Notes

For information on Chandos, see Susan Jenkins, Portrait of a Patron: The Patronage and Collecting of James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos (1674–1744), Aldershot 2007.

Daniel Defoe, A Tour thro‘ the Whole Island of Great Britain, vol.2, London 1725, Letter III, p.8.

Lydia Hamlett was Research Assistant (The Sublime Object: Nature, Art and Language), Tate.

How to cite

Lydia Hamlett, ‘Sublime Effect: James Thornhill’s A Ceiling and Wall Decoration and The Apotheosis of Romulus: Sketch for a Ceiling Decoration and Peter Paul Rubens’s Apotheosis of James I’, in Nigel Llewellyn and Christine Riding (eds.), The Art of the Sublime, Tate Research Publication, January 2013, https://www