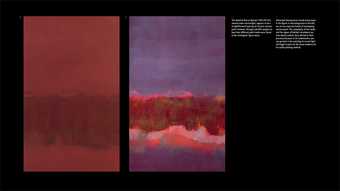

For Tate Modern’s exhibition Rothko, which opened in September 2008, the Interpretation team, working with the exhibition curators, developed a set of interpretative materials for visitors: wall texts and captions, a booklet and a multimedia tour. The number of wall texts was limited but the multimedia tour quite elaborate, including poetry, music and different perspectives on the work. The booklet provided the overall idea of the exhibition and context, while the multimedia tour focused more on the (appreciation of the) object, providing help to look at the works.

The Interpretation team was interested in what kind of visitors were coming to the exhibition and how they would respond to the interpretation material on offer. In this same period a colleague from the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam (Renate Meijer) temporarily joined the team. The Rijksmuseum had conducted several audience surveys in which educational resources were tested on visitors with different levels of experience, confidence, or, to borrow Pierre Bourdieu’s term: ‘cultural capital’. The Tate Interpretation team wanted to look at the exhibition resources from this point of view. We decided to compare this model with a visitor segmentation framework already developed for Tate in 2004, based on the behaviour and motivation of visitors: ‘Anatomy of a Visit’, Morris Hargreaves McIntyre, 2004.

The team was interested to see how both methods were interrelated and how they would be able to shed light on the interpretation material. The survey aimed to discover:

- how people use and value the educational material during their visit to the exhibition (separately and in comparison)

- how people perceive and value the type of information, its layering/distribution and tone of voice

- how the techniques and materials room affect the experience of the visitor of the exhibition as a whole

- how all this relates to their visitor type according to the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam (RMA) model

- how all this relates to their visitor type according to the Morris Hargreaves McIntyre (MHM) model

- the possible relationship between these two types of visitor segmentations.

The hypotheses were:

- different visitor types have different responses to the exhibition as a whole, to the interpretation material and to the techniques and materials room

- combining the MHM and RMA segmentation will produce useful ways of looking at interpretation resources.

There were a few assumptions that needed to be tested as well, such as:

- visitors read wall texts first

- the booklet is not read completely inside of the exhibition but often taken home

- the multimedia tour is self-sufficient, meaning that a multimedia tour user may look at the wall texts but hardly consults the booklet.

Our survey, conducted in November 2008, consisted of three elements:

- a pre-visit questionnaire (to establish visitor types, as well as expectations regarding the exhibition and the interpretation material)

- observations of visitor behaviour in the exhibition itself (to see how visitors engaged with the art and resources)

- post-visit interviews (to learn about the experience of exhibition, resources and behaviour and link this to visitor types).

The questionnaires (fifty in total) were filled out in the Level Four concourse, just outside the exhibition or near the ticket office in the Turbine Hall. The observations were conducted inside the exhibition rooms and separated into two different surveys: one that examined the behaviour of visitors in the first three rooms (twenty-six in total), and one that examined people visiting the materials and techniques room (Room 4; twenty-four in total). The interviews (nineteen in total) were conducted in the café on the fourth floor concourse. The interviewees were approached when exiting the exhibition and some were especially recruited near the ticket office, in an attempt to get a more varied range of respondents. The data was analysed using consumer research software provided by SurveyMonkey. This report is a combined analysis of the findings of the questionnaires, observations and interviews, divided into a general section and findings per segmentation. We then compare the methods used and look at their relevance for interpretation purposes. Even though our survey has provided us with many interesting results, there are some limitations to the chosen method of evaluation – something that is also discussed in this report.

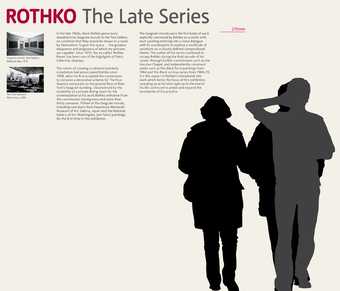

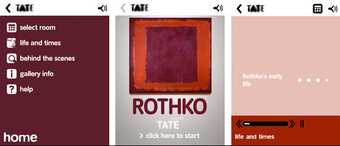

Fig.1

Visitors looking at interpretative material in Room 4

Rothko exhibition, Tate Modern

Photograph by Simon Harvey, Ltd Limited

2 General findings

2.1 (Expected) exhibition experience

The exhibition curator chose not to focus particularly on the spiritual or emotional aspect of Rothko’s work. He wanted to present the art works as physical objects that were actually made by someone (hence the emphasis on materials and techniques in Room 4). On the walls of the exhibition café Rothko was quoted as saying, ‘If people want sacred experiences they will find them here. If they want profane experiences they’ll find them too. I take no sides.’ We were curious how this curatorial decision would affect visitors’ experience. To assess the impact of the exhibition narrative we compared the expectations of the visitors before their visit to their description of their experience afterwards.

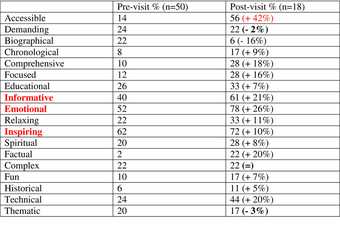

In the pre-visit questionnaire we asked the visitors to choose, from a list of eighteen buzz words, how they would describe their expectations. In the post-visit interviews we asked our respondents to describe their experience, using the same list of words. The experience, to a large extent, matched the expectations: the words ‘inspiring’, ‘emotional’ and ‘informative’ had the highest scores in both surveys (see Table 1). However, each of the interview respondents (who had already visited the exhibition) chose more words, so the post-visit scores are on average 13 per cent higher. There are some significant differences, however, that show that the exhibition exceeded expectations. It was considered much more accessible, and a lot less demanding and complex than expected. It was also less of a thematic overview than people thought.

Table 1

Choice of buzz words

Some caveats: even though we used percentages to interpret these findings, the numbers are too small to make quantitative statistical claims. Additionally, our choice of words was made in consultation with the Interpretation team, and was not part of a pre-existing linguistic research model. It would be interesting to try out this same list in surveys of other exhibitions. It might turn out that visitors always use words like ‘inspiring’, ‘emotional’ and ‘informative’ to describe their expectations and experience of an exhibition. However, we tend to think that at least the first two can be applied specifically to Rothko. The curatorial emphasis on materiality does not seem to have influenced the emotional response to Rothko’s work.

If we look at how the interview respondents describe their expectations and actual experience, experience or cultural capital made a significant difference. Inexperienced visitors did not know what to expect in advance but emerged from the exhibition feeling positive about it. They described their experience uncritically in terms like ‘red is a powerful colour’. Visitors who were more confident, already familiar with Rothko – ‘I knew I loved his work and expected it would be stunning’ – were more open to engaging with the work. The most experienced also knew that this exhibition would focus on his later works and tended to be the most critically engaged when it came to assessing the exhibition as a whole (agreeing or disagreeing with the curatorial thesis, and so on). For example: ‘Rothko himself was freer in his attitude to his own work than the curator.’

2.2 Use of resources

The questionnaire showed that:

- 43 out of 50 (86 per cent) were planning to read the wall texts

- 31 out of 50 (61 per cent) were planning to read the booklet

- 16 out of 50 (32 per cent) were planning to use the multimedia tour.

If forced to choose one resource, most people would opt for the wall texts.

This preference for wall texts was to some degree supported by our observation findings: on entering the exhibition 77 per cent of visitors read the introductory text, with 70 per cent doing this before engaging with anything else (see 2.6.1). Our figures have almost certainly been affected by the fact that multimedia tour users tended to have scheduled more time for the exhibition experience and felt more relaxed about stopping for a questionnaire. The 32 per cent multimedia use observed here is much higher than the average pick-up rate recorded by Antenna Audio (11.72 per cent). It is worth noting, however, that the correct pick-up figures are still very high compared to other exhibitions (usually 7–8 per cent); the multimedia tour for the permanent collection is used by only 1 per cent of visitors.

2.3 Relationship between resources

In our entrance questionnaire we tried to determine what visitors expected from the content of the different resources. Did they expect different information or style from the different interpretation media on offer?

Our questions addressed three different aspects of the content: type of information, tone of voice and complexity. Visitors were divided about the question if the tone of voice would be the same or not. Two thirds of the respondents expected the complexity of the resources to be different across resources: they expected the wall texts to be simplest and the multimedia tour to be most complex. However, we found that the term ‘complexity’ could be interpreted in two ways: difficulty of the text – which was what we wanted to ask – or volume and diversity of the information – which was how people usually interpreted the question. They would reply by saying, for example, ‘most information is in the multimedia tour’. Almost everyone expects the type of information to overlap across resources. When we asked what kind of information the different resources were likely to provide, they all assumed wall texts and captions would be the most factual and provide the bare minimum: descriptions of the works as well as fact and figures. The booklet was thought to provide similar information, but also more background: (art) historical context, information about Rothko’s artistic development, motivation of the artist and also some human interest details and help to look more closely at the works. The multimedia tour was considered to cover everything and to be the ultimate resource for getting different perspectives. Information on materials/techniques was expected to be in all three resources (least in the wall texts and most in the multimedia tour). Of all these types of information, visitors found Rothko’s artistic development and motivation most interesting. The respondents generally thought that the educational resources were designed for different audiences, but there seemed to be very different ideas about which groups the different materials were serving. Some people thought the content of the resources was the same and the multimedia tour was just designed for ‘people who are too lazy to read’.

There were quite a few contradictory ideas: ‘Families won’t use multimedia tours’ versus ‘multimedia tour is for young kids’; ‘multimedia tour would provide a good introduction to the subject’ versus ‘multimedia tour is for more in-depth learners’. People agreed on the time aspect: the multimedia tour was for people who had more time and did not mind spending the extra £3.50. If one did not have much time or money, one only read. Wall texts were the first layer of information, useful if you were pressed for time or did not feel like using extra material. Some people thought that they were very similar to the booklet: ‘factual content a lot like the booklet’. Others stressed that the booklet went into more depth than the wall text and compared the booklet with the multimedia tour: ‘similar to the multimedia tour – just a different format’. Some people said the resources were used by people ‘with different learning styles’. And some mentioned that the multimedia tour offered a different type of information – more emotional, human interest. It was not widely known that the multimedia tour presented the audience with more perspectives on the work and that music and poetry were included. It could be a good idea to make more effort to inform the audience about this.

2.4 General appreciation of resources

The following sections present a summary of visitors’ assessment of the accessibility and content of the interpretation resources in the exhibition. Visitor feedback on the multimedia tour was more in-depth than on other, text-based, resources. This is because we spoke to a high proportion of multimedia tour users (compared to average take-up of the resource). We also found that a visitor using the multimedia tour was unlikely to use any other interpretation resource in any depth during their visit. The high proportion of multimedia tour users among our respondents is, in part, explained by our offer of a free guide to the inexperienced visitors we invited to participate. Even when we requested that these visitors pay attention to all the interpretation resources on offer during their visit, their post-visit responses demonstrated that the tour took priority.

Multimedia tour

This was generally found to be an extremely accessible resource. Visitors described it as ‘easy to listen to’ and ‘not too highbrow’. International visitors also noted that they found listening more accessible than reading. The content was greatly appreciated by the full spectrum of visitors. The layered structure allowed visitors to tailor the content to their own needs. Visitors were still more familiar with the format of audio guides and some did not feel video needed to be used quite so much. As noted above (2.3), visitors’ preconceptions about the multimedia tour before using it or when deciding not to opt for it, varied widely. Some expected a very easy, ‘dumbed-down’ introduction. Others thought it would contain exactly the same content as the booklet in audio form, or expected it to go into even more depth than other resources.

Wall texts

Visitors generally assumed that wall texts would be the most straightforward resource and they were very widely used. The introductory text was read by three-quarters of visitors, and in the rooms where a wall text was offered, it was the first resource turned to by most visitors. Visitors with different levels of experience reported using wall texts in different ways – to give structure to their visit or to enable them to make their own route. As with the multimedia guide, visitors’ preconceptions about the wall texts were very diverse. They seemed to be understood as a resource that needed the smallest commitment in terms of time, and so were expected to be suitable for people in a hurry or for visitors who wanted to relax. Paradoxically, while the resource was not seen as particularly complex, some respondents suggested that it was the resource most suited to very knowledgeable visitors who needed little contextual information and/or ‘just want to commune’ with the works.

Booklet

This is often assumed to be the most high-brow resource. Those who used it in the exhibition found it helpful, but 50 per cent saved it to use after their visit. The photographs of Rothko’s studio were particularly appreciated. This resource was used by more visitors and with deeper engagement in rooms where seating is provided. Visitors tended to expect the booklet to be the resource designed for the most serious visitors or ‘for people who want the catalogue but can’t afford it’.

Room 4 conservation lightboxes

Most visitors found the lightboxes accessible and engaging: this room had a high dwell time (see fig.1). Those who did not engage with it were either put off by the scientific approach or had issues of physical access. The new insights provided in this room were generally greatly appreciated, with many visitors reporting that this section changed their viewing habits in later rooms. The majority of visitors we spoke to would like similar resources in future exhibitions. Even those who were not interested in conservation were still glad that the information was available for others. Visitors tended to be surprised by this section and were not expecting this kind of content in the Rothko exhibition.

2.5 Behaviour in exhibition: method

We observed visitors’ behaviour in the first four rooms of the exhibition. Selecting subjects at random as they entered the first room, and then following them at a discreet distance, we completed an observation sheet which recorded choice of interpretation resources, the order in which resources were used, the balance between using the resources and engaging with works, and ‘dwell time’ in each room. [See pdf download for full observation sheet.] We also categorised visitors’ behaviour according to the following categories developed by MHM:

Ways of moving around the exhibition:

- browsing (‘window-shopping’, wandering aimlessly between works/resources)

- following (a conscientious, route-following approach – seeing everything ‘in order’)

- searching (more confidence, suggesting some prior knowledge of subject matter)

- choosing (most confident – actively picking works/resources of interest and engaging deeply).

Level of engagement:

- orientation (very cursory attention, ‘checking out’ the resource and moving on quickly)

- exploration (spending a short amount on inspection of resource/work)

- discovery (stopping, looking, taking it in)

- immersion (stopping longer, taking it in more deeply, considering – possibly bringing work/resource to the attention of a companion and discussing it).

We split the observation into two sections: Rooms 1 to 3, for the sake of comparing initial behaviour in Room 1 with engagement with the Seagram Murals in Room 3; and Room 4, to focus on reactions to technical information.

The rooms were very different: Room 1 had an introductory wall text and showed small works (sketches); Room 2 had a single work, no wall text and no seating; Room 3 was a large room with an installation-style hang, no wall text and a lot of seating; Room 4, which was developed in collaboration with the Conservation department, centred on Rothko’s materials and techniques and contained a lightbox along one wall, showing photographic details of a painting shot in different types of light, as well as the painting itself and several photographs of Rothko’s studio. Our choice to limit our observations to these rooms was also directed by the practical concern that by shadowing visitors beyond the third room we might attract their attention and so affect their behaviour. Our concern not to influence visitors’ movement or make them self-conscious about their behaviour also meant that we did not ask the people we observed to fill out questionnaires. Consequently, we were not able to screen the visitors and determine their segmentation profile or level of experience. For information on links between observation and visitor segmentation, see Appendix 2, ‘Social spacers’.

2.6 Findings: Rooms 1 to 3

2.6.1 Getting organised

The following findings are based on our observation of twenty-six visitors in the first three rooms. We were particularly keen to observe behaviour patterns in Room 1 to understand of how visitors ‘get organised’ as they approach the exhibition experience: how they make sense on what is on offer to them and the choices they make (Room 1 was one of the few rooms where all three interpretation resources could be accessed). We found that their initial behaviour was not necessarily indicative of how they would engage with the rest of the exhibition:

54 per cent enter the exhibition alone

96 per cent of visitors take an exhibition booklet

19 per cent enter with a multimedia guide (n.b. This figure is significantly higher than the average pick-up rate of 11.72 per cent as recorded by Antenna Audio and may have been affected by our research being carried out on weekdays).

It should be noted that around half of the visitors we observed spent less than two minutes in Room 1, which suggests that in many cases visitors are scanning text for a sense of the overview, rather than immersing themselves in this resource. The number of visitors moving to the introductory text first is marginally lower (60 per cent) for multimedia tour users, but still indicates that, regardless of other interpretation choices, the majority of visitors look first for a wall-text introduction to frame their experience. These findings probably confirmed what we might expect, but the fact that the introductory text was used by visitors across different confidence levels was worth a little more consideration. Our interview respondents provided some feedback on their motivation for reading the wall text: one (highly confident) visitor appreciated that the ‘concise overview’ provided ‘enough information to enjoy the room’; another less assured visitor explained that the introductory text was crucial ‘so you know what to expect’. These different forms of appreciation indicate a wider pattern: confident visitors use the introduction to gather context, allowing them to negotiate the works with informed agency (i.e. giving them the freedom to develop their own route and approach). Less confident visitors look to the introduction for stability – to ward off surprises and give them a framework for what they are about to experience. More information on how confidence affects exhibition experience is provided in the segmentation analysis section of this report (see Appendix 1).

2.6.2 Choosing resources

Choice of interpretation resources (n.b. These figures do not represent exclusive use of these resources, which were very often used in combination):

77 per cent of visitors read the introductory wall text

50 per centof visitors use the booklet

19 per cent of visitors use the multimedia tour

8 per cent of visitors use no interpretation resources

Several visitors using multiple resources simultaneously were observed in Room 1. A fairly regular behaviour involved listening to the multimedia tour introduction while reading the wall text. Another repeated pattern was glancing briefly at the booklet and then engaging with the wall text (suggesting that the content was being compared). One post-visit interviewee explained, ‘You almost need an introductory room to get organised’. Further research is needed to assess whether making sense of the resources on offer in the first few rooms of an exhibition distracts visitors from engaging with the works on display in those initial spaces.

Visitors’ engagement levels with works and/or interpretation resources increased between Rooms 1 and 3. Visitors often shifted the focus of their engagement from art work to interpretation or vice versa between Rooms 1 and 2, and Room 3. We might expect visitors consistently to turn from interpretation to art work – having become familiar with the interpretative resources on offer, the visitor then attended exclusively to the immersive installation of the Seagram Murals in Room 3 (where there was no wall text). Indeed, in Room 3, 67 per cent of visitors looked at the artworks first compared to just 19 per cent in Room 1. However, our observation showed that the inverse was also true, and a visitor who engaged only with works in the first two rooms might well take the opportunity to sit and read the booklet on the benches provided in Room 3. Although 96 per cent of visitors take a booklet, only 50 per cent use it within the first three rooms. Post-visit interview findings suggest that many visitors consciously ‘save’ the booklet to read in the café or on their way home. This raises questions about the booklet as a ‘retrospective resource’.

Comparing the proportion of time spent with resources and works shows some differences relating to multimedia tour use. Visitors with a multimedia tour spend the majority of their time engaging with it, where as non-multimedia tour users spend proportionally longer engaging with artworks. However, multimedia tour users may be engaging with artworks while listening to the tour so it is not always desirable to separate the two types of behaviour. Multimedia tour users do, however, spend longer on average in the first three rooms of the exhibition than other visitors.

2.7 Findings: Room 4

The following findings are based on our observation of twenty-four visitors in Room 4.

2.7.1 Entering Room 4

Fifty-four per cent of visitors entered Room 4 alone. This was exactly the same proportion of visitors who entered the first room of the exhibition on their own, suggesting a general consistency of social habits among visitors. Around a third of visitors were not visibly carrying their exhibition leaflet, confirming that a significant proportion of visitors want a booklet but do not use it during their visit (see 2.6.2). Room 4 showed the lowest proportion of visitors engaging with a painting straight away – 13 per cent (compared to 19 per cent in Room 1 and 67 per cent in Room 3). Instead, visitors tended to approach the wall text (33 per cent ) or the lightbox (25 per cent) before doing anything else. As in the first room of the exhibition, we can see that where a wall text is available, a high proportion of visitors will turn to it first when they enter a new space.

2.7.2 Behaviour at the lightbox

The majority of visitors (71 per cent) approached the lightbox resource. Their levels of engagement with this resource were somewhat polarised, clustering at either end of MHM’s scale, with 30 per cent engaging at ‘orientation level’ and 35 per cent at ‘immersion level’. This pattern echoes levels of engagement with interpretation in the first three rooms in the exhibition. Visitors with a low level of engagement (orientation level) would glance at the lightbox for a few seconds and then move away quickly. The majority of these visitors (67 per cent) stayed in the room for less than two minutes. Our interviewees’ reports of their own behaviour in this room suggested that visitors who did not engage with the lightbox were either put off by the crowds and the necessity of queuing to read the lightbox panels in order and/or recognised quickly that the resource offered technical information and rejected it immediately as being irrelevant to their experience of the exhibition. Our observation also revealed that there were some issues with physical access to the lightbox, especially for wheelchair users, visitors with pushchairs, etc. Conversely, visitors who display signs of ‘immersion’ in the lightbox stayed in the room much longer on average (71 per cent stayed for five to ten minutes). The interviewees who reported a high level of interest in the lightbox told us that what they had learned there about Rothko’s technique affected their subsequent approach to works and their way of looking.

2.7.3 Time spent per room

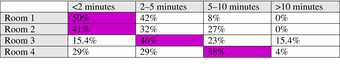

Table 2

Time spent in each Room by observed visitors

The highest proportion of visitors in each room has been highlighted here. Room 4 does appear to promote a relatively high dwell time among visitors, which is especially striking when compared to Rooms 1 and 2 which were of a comparable size. Our findings on the time spent in Room 3 were complicated by the layout of the exhibition: this space was accessible via four different entrances and visitors following the exhibition route in room order still had to cross Room 3 again to reach the exit. Our in-depth observation only covered visitors entering from the first two rooms but our interviewees regularly reported that they returned to Room 3 later in their visit. This tendency needs to be taken into account when assessing relative dwell-time in each room. More research is needed to clarify whether there is a tendency for visitors to slow their pace as they move further into any exhibition, or whether dwell time is affected solely by the works and resources on offer in each space.

2.7.4 Anecdotal findings from interviews

We did not speak to the visitors whose behaviour we observed (see 2.5 on observation method). This gave us a more natural sense of patterns and preferences, but it also proved useful to augment our observation results with descriptions of behaviour provided in the visitor interview section of the evaluation. In some cases this anecdotal information confirms tendencies noted during visitor observation sessions; in others it gives a deeper picture of how behaviour relates to confidence, use of the multimedia tour, etc. Below we present some behaviour patterns that emerged from the interviews.

Multimedia tour users regularly described a behaviour which involves taking in the room as a whole while listening and standing in the centre, some then going to look at individual works:

‘I glanced round first while listening, then moved around.’

‘I kind of took it all in standing it the centre.’

‘Went to central position in each room then looked at everything. Then pressed button and listened to commentary.’

Multimedia tour users who also used text-based resources in the exhibition talked about their experiencing of balancing the two:

‘Reading light box while listening is difficult.’

‘Sitting reading the booklet and listening to music was a very nice combination.’

Visitors either had difficulties or worked out a specific strategy for using both resources at once. One idea to take forward might be to make specific reading points on the multimedia tour, perhaps with music, prefaced by a prompt from the narrator to read the relevant bit of the booklet/gallery text.

Interview responses showed no clear pattern in terms of a route followed through the exhibition. The variation in approaches was perhaps in itself interesting. The interview extracts below have been arranged in terms of the visitor’s experience level (from least to most confident):

‘The one thing I would criticise: the placement of the room numbers. [I got confused.] From Room 3, I went to Room 8.’

‘[We] followed the exhibition route.’

‘I concentrated on Room 3.’

‘I went from Room 5 to 7 to 6 – just followed the colour scheme – so I made my own route.’

‘I liked the exhibition layout – especially seeing Room 3 twice. The second time in there I turned off the multimedia tour, sat and immersed myself for half an hour.’

The diversity of these responses suggests a wide spectrum of orientation needs from visitors (from explicit guidance to freedom to explore). Future research projects may need to compare these orientation behaviours (in an exhibition that does not depend absolutely on an ordered narrative) with those in an exhibition with a more prescribed route established in the layout. The effect of visitor confidence on their experience and behaviour in the Rothko exhibition is examined in more detail in the segmentation section of this report.

3 Segmentation analyses

3.1 Rijksmuseum Amsterdam (RMA) segmentation

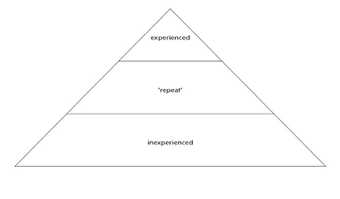

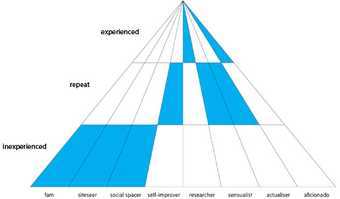

Between 2007 and 2008 the Education department of the Rijksmuseum conducted two qualitative audience surveys in which educational material was tested on different visitor groups. The groups were defined by degrees of museum experience, what in English might be called confidence or cultural capital. This resulted in a simple model, which looks like a pyramid (a shape which is based on the Rijksmuseum audience): the base is formed by the large number of inexperienced (often first-time) visitors and the top is a small group of hardcore museum visitors – the frequent visitor. In between is a section which RMA called the repeat visitor.

Fig.2

Rijksmuseum audience profile

When visitors gain more experience, they can move up the pyramid. Well-designed educational material can help visitors in this process. The Rijksmuseum ‘slogan’ to describe this process is ‘Meer Leren Zien’ (‘learn to see more’, which has a multi-layered meaning: it implicates literally seeing details, but also gaining insight, learning new perspectives, acquiring skills etc.). The three groups all evaluated the same interpretation resources. They had to talk about what they (dis)liked and why and what it was exactly that helped them ‘to see more’. From these two surveys a clear pattern of needs and preferences emerged.

In short:

Inexperienced visitors may very well visit the museum for the first time (but this isn’t a fixed rule). They have little knowledge, want to see the highlights and need a lot of help to get orientated. For them, material needs to be well-structured and information to be basic, short and clear.

Repeat visitors know their way around the museum, but still need help to interpret things. They want to learn, but this mainly means to broaden their knowledge. Material for them should not be too simple but also not be too much in-depth. It needs to be related to what they can actually see.

Experienced visitors are frequent museum visitors, but note that this doesn’t mean that they are necessarily frequent visitors of our museum. Because they have enough cultural capital to interpret what they encounter by themselves, they can be much more relaxed in dealing with signage and interpretation material. They are after deepening their knowledge, so for them contextual information is interesting. This segmentation helped the Rijksmuseum team to think about their audience and to better target their material. The Tate Interpretation team thought it would be interesting to look at their material from the Rijksmuseum point of view.

3.1.1 Method

The research in Amsterdam was executed by a professional company and there were (financial) means to ensure that all segments were covered. The Rijksmuseum respondents were paid to participate and screened on basis of (self-assessed) visit frequency. During the interviews these self-assessments were reinterpreted by the researchers, because although frequency is a good indicator of experience, it is not the same. For the Tate survey it was not possible to invite paid respondents, so we had to recruit amongst the regular Tate visitors. Most of the people who filled out questionnaires or participated in interviews were ‘real’ Rothko visitors, but we also invited some visitors from the general Tate populace to visit the exhibition and be interviewed.

Our respondents were voluntarily taking part in our research and were not paid. It is possible that this fact had some effect on the depth of some of the research results. We could not force the respondents to devote as much time and attention to the written resources (wall-texts and booklet) as to the multimedia tour. However, using authentic Rothko visitors had the advantage that they genuinely wanted to visit this exhibition and this gave us much insight in their motivation and knowledge of the subject. Our questionnaire respondents were asked to assess their own cultural capital using four questions and a rating system. The questions focused on four aspects of cultural capital: experience as museum-goer, knowledge of (modern) art, interest in (modern) art and importance of (modern) art in the visitor’s life. When interpreting the data we found that we had to separate the first and the last two of these aspects. Museum experience and knowledge are the best indicators of cultural capital: they are acquired in a lifetime. Interest and importance are more individual because they are innate: you are either interested or not. Although interest and importance can certainly be stimulated by experience and improvement of knowledge, they have to be there in a rudimentary form. If we look at the method used, it is clear that self-assessment has its limitations: people cannot judge themselves objectively and sometimes are too confident or too modest. The best way to determine these segments so far has been an assessment by the researchers, based on the interview. The ultimate method to determine these segments via a questionnaire still needs to be found, and it can be questioned whether a questionnaire is the right method at all.

3.1.2 Findings: Cultural capital

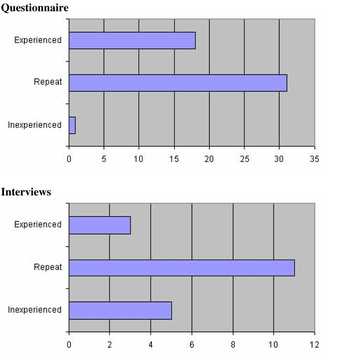

If we look at the results from the self-rating system, we can learn that there were some visitors who gave themselves low ratings, but they were exceptions to the rule. (The lowest possible rating was 2, the highest was 14. We decided a rating of 2-6 was low, 7-10 was average and 11-14 was high. The 69 respondents from both questionnaires and interviews had an average rating of experience/knowledge of 9.5 and an average of interest/importance of 11.3.) If we believe our respondents’ self-assessments, more than half of them could be categorised as experienced (top of the pyramid) and more than a third as repeat visitors. But if we look more carefully at the interviewed respondents – whose cultural capital we could determine ourselves – we find that half of them had overrated their experience. The difference between the two systems of rating is visible in these charts:

Fig.3

Self and external assessment

We had to rely on the self-rating system within the questionnaires, and since people tend to overrate their experience, there were hardly any inexperienced visitors. For the interviews we were able to determine the experience level ourselves, which accounts for the smaller number of experienced visitors. The increased number of inexperienced visitors is also due to the fact that we actively invited some inexperienced visitors to our interviews. This means that neither chart gives a perfect image of the proportions of each RMA segment. There is another caveat: we want to remind the reader that the numbers of respondents of either questionnaire or interview were too small to generate real statistical data, so translating our respondents to charts like these is risky. We do think it is safe to say that the visitors to the Rothko exhibition (or to put it more strongly, to any paid exhibition) are generally repeat or experienced visitors.

There is one striking exception to the tendency of visitors to overrate their cultural capital: there were two interviewees (who we considered to be highly experienced, top-of-the-pyramid) who underestimated their own experience. This confirms the profile of the experienced visitor, who is so confident that (s)he can be modest. The lower levels of experience/knowledge compared to interest/importance are easy to explain: when asked for knowledge, people tend to be self-deprecating, since this is a thing that can be tested. When asked for interest or importance it is more socially acceptable to give oneself a high rating.

3.1.3 Findings: frequency

For lack of better terminology, we tend to use the terms ‘first time’, ‘repeat’ and ‘frequent’ to describe the three layers of the RMA pyramid. Visit frequency can be an indicator of experience, but there isn’t a precise correlation. We asked all respondents how often they had visited Tate Modern. Of the fifty questionnaire respondents:

8 were visiting TM for the first time

17 visit TM once a year or less

20 visit TM about three times a year

5 visit TM every month or more

If we look at their experience/knowledge and interest/importance scores there is no clear pattern at all. This can be easily explained by the fact that many Tate visitors are regular museum-goers, but just have never been to Tate before, or only visit when they are in London. If we want to learn more about a correlation between frequency of visits and cultural capital, we would have to ask for museum visits in general, not just visits to Tate.

3.2 Rijksmuseum pen portraits

In this section we attempt to describe the profile of each Rijksmuseum segment in the form of a so-called ‘pen portrait’. These portraits are based on the interviews we conducted, combined with prior knowledge from the Rijksmuseum surveys. Underneath each pen portrait a table provides the most relevant statistical information. In a separate paragraph we have attempted to describe the possible museum behaviour of each segment. This is absolutely tentative, since we were not able to determine which segments the people we observed belonged to.

See Appendix 1 and 2 for the detailed breakdown of Rijksmuseum and Morris Hargreaves McIntyre pen portraits.

3.3 Morris Hargreaves McIntyre (MHM) segmentation

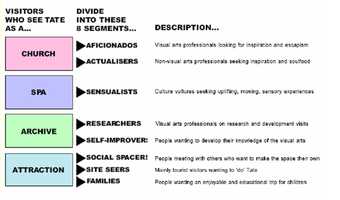

In 2004 Morris Hargreaves McIntyre conducted extensive audience research in both Tate Modern and Tate Britain. This resulted in the report ‘Anatomy of a Visit’. Since, MHM has conducted similar research in other British museums. They have developed methods to rate behaviour and level of engagement which have been discussed above (2.5).

MHM considers motivation and behaviour the two most defining factors to influence the visitor experience. Their research has resulted in a segmentation that recognises four types of motivation for a museum visit: social, intellectual, emotional and spiritual. These four groups can be further divided into eight segments by looking at who the visitor arrives at the museum with (mainly if there are children under fifteen in the party), if the visitor has visited Tate before, and the level of knowledge/whether or not a visitor is a professional. To establish this segmentation, MHM has developed a small but effective questionnaire [see pdf download ]

Fig.4

Eight MHM segments in Tate populace

To find out more about the eight segments, we refer to the individual pen portraits, which are preceded by a summary of the description by MHM in ‘Anatomy of a Visit’.

3.3.1 Method

Since we could use MHM’s questionnaire to determine visitor type, we did not have the problem with self-assessments sketched in [in Appendix 2]. This made it easier to combine information from pre- and post-visit findings.

In this section of our report we sketch a profile of each visitor type as defined by MHM. We present these segments in the order that MHM uses: from social to intellectual, emotional and spiritual visitors. To compile these pen portraits we have combined the information from the pre-visit questionnaires with that of the interviews. We have looked primarily at qualitative information, but also tried to see if there were patterns emerging from the quantitative data of both pre- and post-visit surveys. In formulating the pen portraits we have taken care to indicate on which source the information is based: questionnaires only, interviews only or both. There were three segments that we didn’t manage to interview – families, site seers and aficionados [see 3.3.3] – these pen portraits are purely based on the pre-visit data and the MHM description. By the time we started analysing our findings we had already looked at them from the RMA point of view, so we could start comparing the two segmentation methods. Therefore, we have sometimes made the distinction between inexperienced and experienced visitors.

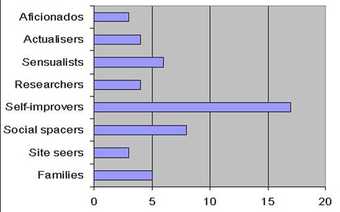

3.3.2 Findings

Of course we can by no means claim to have reliable statistical data, but based on our fifty pre-visit questionnaires we can safely conclude that the Rothko exhibition was visited by a high number of self-improvers.

3.3.3 How many of each MHM segment?

Questionnaire respondents

Fig.5

MHM segments applied to Rothko visitor sample

Considering the nature of Rothko’s work we expected that this exhibition would attract more emotional or spiritual visitors. This does not seem to be the case though. In the MHM questionnaire, respondents have to choose from a list of fourteen statements, reflecting different kinds of motivations. At first, many respondents choose statements from different categories, e.g. both emotional and intellectual motivations. The next step is to choose one statement which is most relevant. It was striking that at this stage a lot of respondents chose an intellectual motivation such as ‘to improve my knowledge or experience’. It would be interesting to see if this phenomenon occurs at other exhibitions as well. For this, we would have to look at the populace of different exhibitions.

3.4 The interrelation of the RMA and MHM segmentations

In this survey we have looked at the same questionnaire and interview respondents through two lenses: one of experience/cultural capital (RMA) and one of motivation and behaviour (MHM). It has been an interesting journey to see how these methods complement each other. There has been not one moment when we thought they were contradictory but there have been times when we were wondering if, for instance, we should see Aficionados as repeat or experienced visitors. The reason to start comparing these two types of segmentation in the first place was that both methods are looking at the psychographic (attitudes and lifestyles) rather than demographic characteristics of a visitor. The two methods are related, but how?

3.4.1 Comparing the RMA and MHM segmentations

Understanding visitor experience/cultural capital helps us target the level of complexity of our interpretation resources. It also helps us understand the type of information visitors are interested in. And it can give us an indication of how people move through an exhibition, how much structure they need. The second RMA survey has shown that involvement and interest in a subject influence the information needs of a visitor. Someone who has little knowledge and experience can be compared to a repeat visitor if this person is really interested or for instance professionally involved with the arts.

The MHM method takes this into account. The questionnaire checks not only visit frequency but also knowledge and professional involvement of a visitor. It combines this information with motivation. And this aspect has proved to be a very rich source of information. Every museum visitor is interested in something, whether it is a relaxed day out with their family or a deep spiritual encounter with art. To ask people for their motivation teaches us a lot about their level of engagement with the art works but also about the type of information they might be interested in and the way they are bound to move through the exhibition. This is a more in-depth way of looking at visitors than the RMA model, which only inventories whether people show interest or not. This refinement can also complicate things when discussing which segment a visitor is in. After an interview it is easier to agree on the cultural capital of a respondent than to decide if someone is a sensualist or an actualiser. But that’s why MHM has developed this sophisticated questionnaire. Since we have not yet found a satisfactory way to determine cultural capital through a questionnaire, the RMA method has been most useful in qualitative research. Self-assessment has not proved to be a very reliable method.

There is an important difference between the two methods. The RMA approach pins people down in a certain category (level of experience). Once you have gained confidence, you are unlikely to lose it again: the movement in the pyramid is up. MHM does not disagree with this, but has a more flexible approach. They look at individual visits rather than visitors. Someone who is highly confident may behave like a researcher when alone but like a family when with children. An inexperienced visitor may behave like a site seer when with peers but like a self-improver when accompanied by an aficionado.

3.4.2 Combining the RMA and MHM segmentations

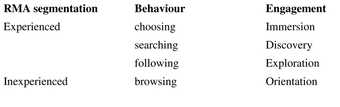

MHM not only recognises that visits can be different, but also that things can change within one visit. In section 2.5 we have discussed the categories developed by MHM to indicate ways of moving around an exhibition and to describe levels of engagement. The intensity of a visit usually differs in each stage of the visit: a visitor can move from orientation to immersion or from browsing to choosing and back.

Museums want their visitors to have a high-quality visit. They want to encourage people to immerse themselves with the art works, to move up the ladder of engagement. This reflects an idea of development similar to the three experience levels in the RMA pyramid. One could loosely describe this pattern thus:

Table 3

Ladder of engagement

The word ‘loosely’ should be noted. These categories are interconnected but not equal: someone who is browsing is unlikely to go beyond the exploration stage, but we cannot go so far as to say that browsing equals orientation. Furthermore, as stated before, one can move up and down the different stages of behaviour and engagement. This exercise helps us to link the RMA three-layered pyramid with the eight MHM segments. We have attempted to integrate the two in this tentative model:

Fig.6

RMA pyramid and MHM segments linked

Social visitors are unlikely to go beyond orientation/exploration and usually show browsing behaviour. This is consistent with the fact that the motivation for their visit is not intellectual. These people have similar information needs as the inexperienced visitors of the RMA. If they are social spacers they may be very frequent visitors, but they are not interested in engaging too deeply since their main aim is to be social. In the case of families there is the paradox that the parents may belong to an entirely different segment when they visit as individuals. They could be art professionals in their working life, but when they arrive with their children they are viewed as family visitors. We have not met enough families in our survey to be absolutely certain about their position at the bottom of the pyramid: it is possible that a very experienced parent can develop choosing behaviour and guide the child to a high level of engagement. This is not likely to be the case with most families though. Several families that we approached to fill out questionnaires before their visit had exited the exhibition within half an hour. This does not indicate deep immersion into the exhibition.

The top of the pyramid is occupied by the two segments of arts professionals: researchers and aficionados. This corresponds with the RMA findings that really experienced visitors have often studied art history or have undertaken educational courses. These people want to deepen their knowledge, whereas the middle layer is looking for broadening their knowledge. In this layer we have placed the self-improvers, sensualists and actualisers. This is the layer that we have got to know best during our survey. As stated before, this integrated model is tentative. The example of the family shows that the horizontal lines in this model are not to be regarded too strictly. It can also be argued that social spacers are higher up in the pyramid than the other social visitors, because they have discovered that the museum is a place they want to spend time more often: this is the beginning of an intellectual motivation. However, our integrated model does help us to understand both segmentations better. We now know that the middle layer of repeat visitors are likely to be self-improvers, sensualists and actualisers, who have intellectual, emotional and spiritual motivations for coming. It also works the other way around: if we want to cater for the needs of a site seer, we should remind ourselves that we are dealing with a social visitor with little cultural capital.

4. Conclusions

We set out to gather information on visitor responses to interpretation in the Rothko exhibition and to observe patterns in these results when different forms of segmentation were applied to the responses. Through this analysis we have developed a much stronger understanding of the MHM and RMA segments, specifically as they relate to visitors’ interpretation preferences. In the case of the MHM segmentation, we have demonstrated that this particular method of visitor taxonomy can be usefully applied to questions of education provision – an extension of its existing use at Tate by the Marketing and Visitor Services departments.

By creating pen portraits of each segment we have been able to assess the successes and drawbacks of the Rothko interpretation resources for different visitor profiles. Our findings can also be applied to producing resources targeted at particular visitor segments in future projects. This can be used to better tailor interpretation material, programmes or even exhibitions to the needs of existing dominant sections of the visitor demographic, and/or to develop new audiences by creating resources for specific, underrepresented, segments. If we want to reach inexperienced visitors and encourage them to visit temporary exhibitions, for example, we now know we need to address their social needs and interests.

Through applying the two different segmentation methods, we now have a clear map of the intersections between visitor motivation and experience; if we want to reach repeat visitors, for example, we know that they are likely to be self-improvers, sensualists or actualisers (and vice versa). Looking at MHM and RMA segmentation in tandem also helps to underline the fact that visitors’ profiles are not static but can change according to the conditions of their visit and as they gain confidence and experience over time. We had hoped to get a picture of how visitors use interpretation materials in combination – i.e. which resource they turn to at a particular point in the exhibition and why. Our research showed that most visitors are ‘loyal’ to either the multimedia tour or text-based resources throughout the visit itself, however, so drawing out meaningful comparisons in terms of tone or content proved difficult. Knowing that most visitors currently adopt an either/or approach is helpful – should interpretation resources reference one another (e.g. ‘you can read more about this in your booklet’ on multimedia tour)? Or does it make sense to have more of an overlap of content between platforms?

4.1 Ideas to apply

We can now apply the findings in this report to design interpretation for specific visitor segments. The next stage is to experiment with consciously targeted resources. Instigating a policy discussion within the Learning department will then be important to assess whether we go on to tailor resources to existing segments or to audiences we are seeking to develop (or both simultaneously). It is not widely known that the multimedia tour presents the audience with more perspectives on the work and that music and poetry are included. It could be a good idea to publicise the diverse content of the multimedia tour at the entrance to the exhibition. Indeed, this could be applied to all interpretation material: visitors expressed varied expectations of all resources, suggesting that more information should be provided on what each offers. Sharing the segmentation analysis from this report (especially the Pen Portraits) with the Antenna sales team will help them to assess a visitor’s needs (as a Sensualist, or Social Spacer, etc.) and point them to resources on the tour that are most likely to provide them with a rewarding visit.

Responding to a general visitor tendency to choose either multimedia or text based resources, the interpretation team might want to consider finding ways of encouraging visitors to use both resources. For example, by providing specific reading points on the multimedia tour, perhaps with music, prefaced by a prompt from the narrator to read the relevant section of the booklet or gallery text. Another approach would be to make an overlap of content between platforms standard practice, perhaps bringing some of the features of the multimedia tour into the paper guide, such as excerpts from expert interviews. Visitors read their leaflets much more intently when they can sit down. Interpretation should be factored in from the early stages of exhibition design, ensuring that spaces for reading and listening are provided at key points within every exhibition. Many visitors consciously ‘save’ the booklet to read in the café or on their way home. This raises questions about whether the booklet needs to be thought about specifically as a ‘retrospective resource’.

4.2 Methodological questions/further research

We know that inexperienced visitors make up a very small proportion of temporary exhibition visitors in general. More research on this segment and its needs and preferences is needed to get a fuller idea of what would make temporary exhibitions more inviting to this under-represented group. Our list of buzzwords from which visitors picked to describe their expectations or experience (2.1) was made in consultation within the Interpretation team, and is not part of a pre-existing linguistic research model. It would be interesting to try out this same list when researching other exhibitions. We could then get a clearer picture of whether visitors always use words like ‘inspiring’, ‘emotional’ and ‘informative’ to describe their expectations and experience of an exhibition, or whether these terms are specific to Rothko. Further research is needed to clarify whether there is a general tendency for visitors to slow their pace as they move further into any exhibition, or whether dwell-time is affected solely by the works and resources on offer in each space.

Future research projects may need to compare orientation behaviour in an exhibition that does not depend absolutely on an ordered narrative with those in an exhibition with a more prescribed route established in the layout. It would be helpful to develop more sophisticated methods assessing the effect of interpretation on engagement with art works – either through further research or literature review. Our phenomenological method of observation did stumble when it came to multimedia tour use. We are left with some questions as to how to assess levels of engagement when it is not a question of either looking at a work or reading text, but listening and looking intently at the same time.

4.3 List of appendices

1. Rijksmuseum pen portraits

2. Morris Hargreaves McIntyre pen portraits

3. Summary of multimedia tour for Rooms 1–4

4. The following questions and forms can be downloaded in pdf format [PDF, 67KB]

1. Rothko entrance survey

2. Morris Hargreaves McIntyre segmentation questions

3. Observation sheet

4. Post-exhibition interview questions

APPENDIX 1

Rijksmuseum pen portraits

In this section we attempt to describe the profile of each Rijksmuseum segment in the form of a so-called ‘pen portrait’. These portraits are based on the interviews we conducted, combined with prior knowledge from the Rijksmuseum surveys. Underneath each pen portrait a table provides the most relevant statistical information. In a separate paragraph we have attempted to describe the possible museum behaviour of each segment. This is absolutely tentative, since we were not able to determine which segments the people we observed belonged to.

Inexperienced visitors

According to the segment summary developed by the Rijksmuseum, inexperienced visitors don’t bring much knowledge or contextual understanding; they need structure and an explanation of how what they are seeing relates to them, they also frequently get lost inside the museum. None of the inexperienced visitors we interviewed came especially for the exhibition, apart from one man who was accompanying his wife. With this one exception, all our inexperienced interviewees were invited to visit the exhibition having completed a screening questionnaire that established them as infrequent/inexperienced museum visitors. Our need to recruit visitors to research this segment confirms that inexperienced visitors are very unlikely to visit a temporary exhibition. The people we spoke to had little contextual knowledge which would inflect their engagement with the exhibition. Two out of five had never heard of Rothko before their visit. Yet all five visitors enjoyed the exhibition.

The inexperienced visitors were characterised by their lack of confidence in their own interpretative abilities:

‘It’s not my type of art so it [multimedia tour] really helped me.’

‘I don’t know anything about art.’

‘I kind of took it all in standing in the centre, I don’t know enough to analyse and stuff.’

‘I don’t understand art.’

The inexperienced visitors reported more problems with orientation than repeat and experienced visitors; figuring out a route through the exhibition or matching the multimedia tour commentary to the room they were in proved confusing. There is little interest in the conservation information in Room 4:

‘… wasn’t really interested in [this] technical part…’

‘.. too many people so I didn’t spend too much time there…’

This is in contrast to a strong interest in biographical information.

They tended to express their appreciation for interpretation resources in terms of dependency (in this case multimedia tour):

‘Without the multimedia tour I would’ve just walked around.’

‘I wouldn’t have found it as fascinating if I hadn’t had the audio.’

‘I wouldn’t have got as much information.’

‘This is not my type of art so it really helped me.’

Despite seeing the multimedia tour as very useful or even essential, they didn’t view/listen to all the segments in the tour. Some mention that there were parts of the exhibition or resources they don’t remember very well. They seem less concerned than repeat visitors about getting ‘the full experience’. They tended not to use the booklet in the exhibition, or only refer to it initially. This is influenced by multimedia tour use. It will be kept as a ‘souvenir.’ Wall texts were read more frequently and receive positive or neutral feedback. Inexperienced visitors have difficulty summarising the exhibition narrative and do not speak very confidently or at length about their own experience of the show as a whole.

Inexperienced behaviour – some tendencies

Through a combination of the observation section of our analysis and interview findings, we have developed a portrait of the behaviour patterns of a ‘typical inexperienced visitor’. We offer this very tentatively, however, emphasising that not every inexperienced visitor will display all of these tendencies. The typical inexperienced visitor spends little time with any one work or resource and their visit to the whole exhibition is comparatively short. S/he tends to drift between resources or works and may have difficulty in juggling more than one interpretation resource. S/he is often becomes confused about the exhibition route and is easily put off by crowds around resources or works. If not visiting alone, s/he will potentially spend a large proportion of visit time talking to companion about non-exhibition related subjects.

Repeat visitors

According to the segment summary developed by the Rijksmuseum, repeat visitors come with some general knowledge and context, and want to broaden their knowledge during their visit. Because of this, they seek out and use interpretation material in order to learn more. Most repeat visitors we spoke to had some prior knowledge of Rothko, though rarely knew that this exhibition would focus on his later works. They tended not to define themselves or their own knowledge level explicitly, but did imply a level of confidence by expressing concerns for other visitors who might experience problems:

Multimedia tour might be ‘difficult for people not used to technology’.

‘People who are not experts would be able to understand and see with a little more depth.’

‘Foreigners might find wall texts easier [than booklet].’

This segment of visitors articulates ‘what was missing’ more clearly than experienced and inexperienced visitors. The majority of repeat visitors have suggestions about information they would like to have had access to and/or they format in which it is made available, although there is no definite pattern about what that missing info is. Their concern with missing information further indicates a preference for materials that provide a broad context.

Four out of ten would like more biographical context:

‘Would like to know more about what went on in his head and in his heart.’

‘More biographical details perhaps would have been interesting.’

These visitors are almost universally positive about the technical information in Room 4. Several suggest that understanding technique and layering helps one to appreciate the value of Rothko’s work – countering the ‘I could do that’-reaction which they expect from less well-informed visitors, e.g. ‘It might have made my lager drinking football fan boyfriend think about how it’s done [Rothko’s art] and how innovative and skilful it is’. When describing their general impression of the show, around half talk about its emotional effect:

‘There was a sort of sadness…it was quite emotional.’

‘Something moves you – you don’t know if it is ecstatic or melancholic – it just moves you.’

Hypothesis: Repeat visitors are most open to an emotional/visceral reaction to the works; they are neither preoccupied with the unfamiliar setting and resources on offer, as an inexperienced visitor might be, nor do they have the highly developed background knowledge and ‘unsurprisable’ stance of an experienced visitor.

Repeat behaviour – some tendencies

Through a combination of the observation section of our analysis and interview findings, we have developed a portrait of the behaviour patterns of a ‘typical repeat visitor’. As with our portrait of inexperienced behaviour, we offer this very tentatively, emphasising that not every repeat visitor will display all of these tendencies:

Typical repeat visitors conscientiously absorb the interpretation resource chosen and are unlikely to use multiple interpretation resources at once. They move around each room in sequence and are the most likely among the three experience segments to take notes. If visiting with a companion, they will discuss the work by swapping contextual insights gathered from interpretation during the visit, rather than giving personal interpretations. Repeat visitors probably spend the most time visiting an exhibition, compared to the other two experience levels.

Experienced visitors

According to the segment summary developed by the Rijksmuseum, experienced visitors bring a lot of contextual knowledge to their visit, want in-depth information, and want to make their own selection. They don’t feel dependent on interpretation materials, but have a relaxed, interested approach. All of the experienced visitors we spoke to knew what the exhibition would be about in advance (three out of four had researched it and knew it would be the late works; the fourth was already familiar with Rothko’s work).

They tended to describe themselves with certainty/confidence:

‘I might be better informed than most visitors.’

‘I’m not like all the little girls with their notebooks and pencils doing A-level art.’

In their descriptions of their visit, they make it clear that they are well-informed cultural consumers; when explaining their experience, they invariably make reference to other artists or art forms (e.g. Wagner, early music, Picasso, theatre).

No difficulties with orientation were mentioned – the experienced visitors made sense of the space quickly and moved through it to suit their preferences (e.g. moving straight to Room 3).

Those who use the multimedia tour appreciate the layered structure in particular for the ability to select which areas are of interest:

‘Choice to go into more depth on subjects that interest you, or skim sections that are less gripping: layering.’

As the Rijksmuseum summary notes, these visitors have a relaxed approach to the interpretation resources they use, in the sense that they do not lean on them to direct their experience but appreciate that the multimedia tour can be tailored to suit their interests.

Conversely, those who chose text-based resources assume that multimedia tours are likely to make the exhibition a less personally directed experience:

‘I prefer my liberty, reading when I want to read, etc.’

‘Multimedia tour imposes a certain straightjacket on you.’

No pattern emerges on the type of information that experienced visitors prefer (e.g. some really appreciate the technical information in Room 4, others avoid it) – but they do seem united on their preference for resources that they see as flexible. For experienced visitors to choose a resource, they have to feel that it can be adapted to their particular interests. As we have learned from the Rijksmuseum section, they want the opportunity to delve deeply into certain topics, but do not want to be compelled to take in all material at the same level of intensity. They like to be able to skip or skim.

Experienced behaviour – some tendencies

Through a combination of the observation section of our analysis and interview findings, we have developed a portrait of the behaviour patterns of a ‘typical experienced visitor’. As with our portraits of the behaviour of inexperienced and repeat visitors, we offer this very tentatively, emphasising that not every experienced visitor will display all of these tendencies:

Typical experienced visitors choose what is likely to interest them and move directly towards it. They skim some interpretation resources and engage deeply with others. They spend a long time engaging with chosen works – this may involve an in-depth discussion with a companion. Experienced visitors have no trouble orientating themselves but may choose to miss out whole sections of the exhibition if they decide that they are not of interest.

APPENDIX 2

Morris Hargreaves McIntyre pen portraits

Family visitors

MHM: The behaviour and needs of families are defined by the fact that there are children (under 15) present. No matter how different the interest and experience of parents are, they have in common that they need to occupy, stimulate and engage those children. The level of gallery confidence determines how easy it is for the adults to play this role of facilitator. The motivation and experience of families centres on enjoyment and learning. Our knowledge of the Rothko family visitors is very limited since we didn’t interview any. This was expected because of course it is hard for parents to sit down and talk to us when their children are demanding attention as well. As it was, it was hard to find people to fill out the (whole) pre-visit questionnaire. We did go to the gallery on a Sunday especially to be able to do some questionnaires with families. In all we did five.

Four out of our five respondents mention ‘to encourage children’s interest in art’ as one of their motivations for visiting, but only two name it their main motivation. As individuals these parents of course have their own interests, needs and agenda’s. This explains that they choose other motivations as well: personal interest or to see awe-inspiring or beautiful things. Their personal motivation is clearly the reason they chose to go to the Rothko exhibition. However, we have no information on the number of family visits to this exhibition. It would be interesting to know how many parents actually choose this kind of exhibition to visit with their children. Of course we don’t have any information on how the families we screened before their visit enjoyed the exhibition. It did strike us though, that some of these parents were soon afterwards seen in the café, apparently having ‘done’ the exhibition in a very short time. Only one parent intended to use the multimedia tour. The others said it would be too complicated to combine that with minding their children. Among our interviewees there were a few parents (having an outing without their families), who discussed the possibility of using interpretation material with their children. The multimedia tour would probably appeal to children because it is an interesting and interactive gadget. All parents we talked to mentioned that the music segments in the multimedia tour would really appeal to their children. The rest of the content was not made with children in mind, so would probably be too complex.

Social spacers

MHM: social spacers go to art galleries regularly but see it as a social activity. They like to just drop in and drift around in an unfocused but confident way. They are looking for a way to make the Tate their own, are looking for a ‘way in’.Since we only had one real interview, it is impossible to sketch a full portrait of social spacers (for instance compare their expectations and post-visit experiences). There are, however, some things that we can deduce:

The social spacers coming to the Rothko exhibition are regular (but not hard-core) Tate visitors: five out of ten visit about three times a year. The woman we interviewed wasn’t planning to come today – she was just walking and felt like popping in. This is typical social spacer behaviour. The other social spacer we talked to displayed the same, not very purposeful (?) behaviour: he came along with his wife and let her do most of the talking. There is a big difference in confidence and interest between these two visitors, and consequently a different level of engagement. Although they have very different confidence levels, the two share the need to find ‘a way in’. She: ‘I don’t know much about Rothko, so I need them’, meaning the resources, especially the multimedia tour. He says the multimedia tour ‘really helped’ him: ‘it was explained really well’. Although she does appreciate the information, she calls it ‘overwhelming’. About the multimedia tour she says that there’s a ‘difficult balance between being intrusive and user friendly’. She would’ve been satisfied with just the ‘about this room’ sections and would’ve liked the additional information on a podcast to listen to afterwards (in the car). She does acknowledge that one can ignore parts of the information if necessary. They both show appreciation for written resources, although in his case it clearly has to do with needing solid ground and therefore turning to captions. She: ‘I wouldn’t have gone in without a booklet’, but then in the end she focuses on the multimedia tour.

Site seers

MHM: Site seers are socially driven visitors for whom the destination, building, other visitors and facilities are as or more important than the art. We did not interview any site seers and only did a pre-visit questionnaire with three of them. This is accounted for by the fact that site seers are not likely to visit paid exhibitions. They generally are first-time visitors who are attracted by Tate Modern mainly because of the building. They want to be able to say ‘been there, done that’. The questionnaire results show that they all chose social reasons for coming (the major attraction or interesting building quality of Tate was their main reason for visiting) but they are also emotionally/spiritually motivated. As buzz words to describe their expectations they choose ‘informative’, ‘educational’ and ‘biographical’ but also ‘emotional’, ‘relaxing’ and ‘informative’.

Self-improvers

According to the MHM description, self-improvers tend to be intentional and focused. They come to Tate for intellectual stimulation and to develop themselves. Many are international visitors, so although it may be their first visit to Tate, they have experience of other museums and galleries. For the self-improvers we interviewed, the value of their visit to the exhibition seemed to depend on how much they felt they had learned/how much information was on offer. The self-improvers we spoke to at the entrance to the exhibition primarily expected the show to be ‘inspiring’, with ‘emotional’ ‘informative’ and ‘demanding’ also mentioned frequently. Those we spoke to at the end of the show rated ‘informative’ top with ‘educational’, ‘technical’, ‘emotional’ and ‘inspiring’, each mentioned by half of the interviewees. Findings on both expectations and experience show that a mixture between affective and educational elements are noticed and valued by self-improvers. Some aspects of the contextual information provided was clearly not expected: only 6% of self-improvers at the entrance expected information provided to be technical, while 50% of visitors interviewed after the exhibition used this word to describe it. On the other hand, 28% of the self-improvers asked at the entrance expected the exhibition would be biographical. At the end of the exhibition, none of the visitors mention that term to describe the exhibition. The multimedia tour is a popular choice for self-improvers and was generally highly valued as a transmitter of information. The variety of voices was praised by interviewees not so much for the alternative perspectives it offered, but as way of giving further information:

‘Friends or other artists … add some interesting facts and ideas.’

‘When we hear someone’s opinion or description – it’s very valuable for my knowledge.’

‘Contradicting perspectives … [give me] tools to understand.’

Information-gathering is at the heart of the exhibition experience (though not necessarily at the expense of an emotional reaction). A typical reason for choosing the multimedia tour was one visitor’s claim that contextual information is crucial ‘otherwise you just see the colours and leave.’

‘Just seeing colours’ may be unsatisfactory for self improvers, so they tend to be very enthusiastic about Room 4 of the exhibition. Many appreciate the technical insights of the conservation lightbox (and some have already been thinking about this technical aspect before this stage in the exhibition). The physical reality that underpins the visual effect is appreciated:

‘It helps you look beyond face value.’

‘Technique bit made you look differently.’

‘Good to be aware of [colour layering] – looked for this in later rooms.’