August Sander’s portfolio ‘The Persecuted’ – from the penultimate volume of his posthumously published compendium People of the Twentieth Century – is made up of stark, austere portraits of Jewish men and women determined to leave Germany after the Nazi anti-Semitic campaign intensified towards the end of the 1930s. Little has been written about why a non-Jew like Sander would not only associate with but also take photographs of Jews at a time when the National Socialists were increasingly enforcing racial restrictions against them. Much of the literature on Sander’s work casts the photographer as conservative and over-emphasises the differences between his views and those of his more politically active son Erich.1 This essay will seek to counter this characterisation by examining Sander’s leftist cultural and intellectual friendships during the 1920s and 1930s and by linking ‘The Persecuted’ with another portfolio called ‘Political Prisoners’, made by Erich Sander in prison before he died in 1944. Analysing the two portfolios together helps clarify Sander’s antifascist position after the Second World War and reveals the connections between this position and his earlier political beliefs.

During his life August Sander continually revised the plans he first made in 1925–7 for a major seven-volume compendium of his portrait photographs; he added new groups of images and re-arranged the organisation of the volumes. As a result it was not an easy task for scholars working after his death in 1964 to determine either the order of the photographs within the portfolios or the exact arrangement of the portfolios themselves. Not until 1980 did a major reconstruction of his life-long project appear under the title August Sander: Menschen des 20. Jahrhundert (published in English in 1986 as August Sander: Citizens of the Twentieth Century).2 Twenty-two years later a revised, more definitive seven-volume edition with 619 photographs titled People of the Twentieth Century was published by the August Sander Archive in Cologne.3 Because Sander intended his seven-volume opus to begin with portraits of farmers and to end with portraits of the insane, the physically deformed, and the dead, and because his plan was to group individuals according to their occupations, art historian Ulrich Keller’s introduction to the 1980 publication – in which he emphasises that Sander’s arrangement of his compendium was an outgrowth of the cyclical and evolutionary view of human society propounded by the philosopher Oswald Spengler in his 1922 treatise The Decline of the West – has directed much of the art historical research conducted on Sander’s work ever since.4 Although Keller asserts that Sander was a Social Democrat and that the photographer’s interest in ‘types’ was part of Weimar culture’s fascination with the pseudo-scientific field of physiognomy, Keller comes to the conclusion that Sander was conservative aesthetically and politically.5 Others, such as the photographer Allan Sekula, have maintained that Sander’s quest for universally communicated types shared the mistaken positivist belief in the infallibility of science and liberal politics – belief systems that Sekula felt were easily merged a few years later with the policies of National Socialism. Written in 1981 when attitudes toward socialism’s involvement with parliamentary government was viewed by many Marxists as an unjustified compromise, Sekula further contributed to Sander’s identification as a naïve and apolitical individual while obfuscating the variety of intellectual differences within the left in pre-Second World War Germany.6

This approach is often reflected in scholarly studies of Sander’s first photobook, Face of Our Time (Anlitz der Zeit) of 1929, the only published collection of Sander’s work supervised by the photographer himself. Art historian Andy Jones, disagreeing with Sekula that Sander’s book too closely favoured ‘biological determinism’, found Sander to be siding with the Mittelstand, the lower-middle class exemplified by small businessmen. Although Jones, like Keller, notes that the photographs of the workers and even the unemployed have a heroic quality, he goes on to emphasise the contradictory and ultimately reactionary beliefs of the Mittelstand, again diminishing Sander’s connections with the German left.7 In a lengthy and significant article on Weimar photo essays art historian Michael Jennings rightly emphasises the importance of Sander’s sequencing of photos, but he finds tensions between Sander’s goals and their communicable viability. Although he states that Sander did not pander to the nostalgia of the right, he concludes that the 1929 book was ‘matter-of-fact, even-handed in its political comment, and sympathetic to every segment of society’, a comment that subtly minimises Sander’s commitment to the under-privileged.8 Art historian Daniel H. Magilow, whom Jennings advised for his doctoral dissertation, describes Face of Our Time as a reflection of Spengler’s conservative philosophy in his 2012 book The Photography of Crisis: The Photo Essays of Weimar Germany. He interprets Sander’s decision to place images of the unemployed at the end of the photobook as proof of the photographer’s belief in the decline of civilisation, rather than as support for redundant labourers.9 While the German philosopher Walter Benjamin has been recognised by the majority of these critics for his praise of the photobook’s sociological understanding of the German class system and for his claim that Sander’s work (along with that of the more experimental artist László Moholy-Nagy) pointed to the direction that photography should take in the future, even Benjamin’s analysis of Sander’s work has been questioned, despite the philosopher’s Marxist credentials.10 Many on the new left, reinvigorated by the student protests of 1968 that embraced an anti-Stalinist type of Marxian analysis, as well as those leaning toward the centre, have considered Sander to have been uncommitted or neutral in his assessment of German cultural and political groupings, obfuscating both Benjamin’s claim for Sander’s political positioning and also the multiplicity of factions that viewed themselves as leftist during the Weimar Republic and even during the National Socialist era.

Fig.1

[ORIGINAL_CAPTION]

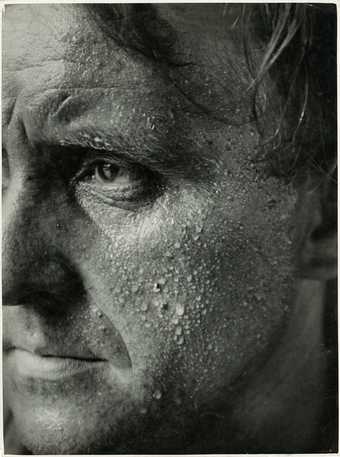

The editors of the revised 2002 edition of People of the Twentieth Century have pointed out that the National Socialist period had a profound impact on Sander. According to the editors, the sixth volume, The City, which includes both ‘The Persecuted’ and the ‘Political Prisoners’ portfolios, was subject to the greatest number of changes and additions during Sander’s lifetime. After the Second World War had ended Sander appended a note to his original list from the 1920s, remarking that he wanted this volume to include ‘Politicians Imprisoned by the National Socialists’ and that he had made prints from the negatives taken by his son in prison for this purpose.11 In a letter written in July 1946 to Hans Schoemann (fig.1), a close friend of his late son Erich, Sander explained that he planned to include in his project a portfolio containing his photographs of ‘Jews who emigrated … mostly old Cologne types’, which he believed would be a ‘magnificent document for the Jewish people’, expressing his long delayed revenge against the National Socialists.12 Several months later, in a letter to a close associate, the writer and editor Dettmarr Heinrich Sarnetzki, Sander mentioned both portfolios: writing about the difficulties of arranging his compendium, he described the process of laying out his passport photos ‘concerned with people who emigrated or breathed their last in the gas chambers’.13

Both ‘The Persecuted’ and ‘Political Prisoners’ provide instantly gripping and sober images, yet they have not been the subject of much discussion or analysis. Few of the portraits of inmates except for the one of Erich working at a prison table (fig.2) have been identified in the ‘Political Prisoner’ portfolio in the 2002 edition.14 Of the twelve individuals in ‘The Persecuted’ portfolio, no names are listed in the revised edition although a few of the last names were written on the negatives. Little is known about the identity and background of the sitters and even less is known about whether they emigrated successfully or died in concentration camps. Arnold Katz (fig.3) is one of those documented to have been taken from Cologne in October 1941 to the Lodzghetto in Poland, who then died or was killed in the Chelmo camp seven months later.15 A 1933 newspaper account and photograph of Katz and his son being paraded through the Cologne streets with derogatory placards during a Nazi demonstration indicates the power of the National Socialists in the city soon after Hitler took over the German government (fig.4).16 Many more negatives of those who asked Sander for exit or passport photos are marked in Sander’s script ‘jude’ on their glassene protectors than were published in the 2002 edition, or even in the 1980 edition, in which the portfolio of his son’s photographs of political prisoners was not included.

Fig.4

Arnold Katz and his son Benno Katz being paraded through Cologne during a boycott of Jewish businesses on 1 April 1933

NS-Documentation Center of the City of Cologne

Sander’s decision to place the passport photographs of Jews in the same volume as his son’s photographs of those imprisoned by the National Socialists should serve as a reminder that Sander not only had a negative attitude toward the Nazi takeover but also had strong political views as well. Scholars usually mention that Sander neither shared the radical political commitment of his son Erich nor approved of his political activism.17 But left-leaning friends of Erich such as the communist leader Paul Fröhlich often visited their home and appear in Sander photographs. Indeed Fröhlich is prominently featured in a three-quarter-length portrait close to the centre of Sander’s Face of Our Time. Sander is known to have assisted his son with the printing of some of the anti-fascist leaflets promoted by the outlawed Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany to which his son then belonged.18 Since the primary targets of the National Socialists in their first year in power were those associated in any way with communism, Sander was certainly aware of the danger Erich faced as a member of a political party that included some communists among the majority of independent Social Democrats. Erich was arrested in 1934 for distributing these leaflets and died in prison ten years later from an untreated ruptured appendix. Two years after his son was imprisoned, the unsold copies of Face of Our Time along with all the printing plates were confiscated by the Nazis and destroyed.

Sander did not openly write about his political beliefs and as a result they remain obscured. But during the 1920s and 1930s the photographer was closely involved with a radical left art group known as the Cologne Progressives, whose members’ works were included in the infamous Degenerate Art exhibition that toured Germany in 1937–8. This exhibition was the culmination of a campaign in which the National Socialists linked Marxism and Bolshevism with modernism and Judaism. Essays in the exhibition catalogue described the political left and modern art as alien and sub-human, claiming that Jews were responsible for the decay of German art even though very few of the artists were of Jewish extraction.19 Jankl Adler and Otto Freundlich, two of the six Jews among the 112 artists defamed in this notorious event, were joined by their fellow Cologne Progressive artists Franz W. Seiwert and Heinrich Hoerle, Sander’s closest friends associated with the group.20 Sandler had photographed all four of these individuals and their work (figs.5 and 6), and a photographic record of Sander’s workroom (fig.7), taken perhaps as late as 1942, indicates that he kept his photographs of Seiwert, who had died in 1933, and Hoerle, who died in 1936, hanging in this room.21 By the time the exhibition came to Cologne’s neighbouring city of Düsseldorf in date, Sander would have seen the cover of the exhibition guide with an image of a Freundlich plaster cast desecrated by the word Entartete (Degenerate) printed in large letters above it.22

Fig.7

August Sander

Sander's studio/home, Cologne: Workroom (Sander's Studio/Wohnung, Köln: Arbeitszimmer) c.1930–1942

Gelatin silver print

224 x 165 mm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© J. Paul Getty Trust

Sander had made contact with a number of artists associated with the Cologne Progressives by 1923, and as a result he expanded and strengthened his anti-establishment views that had begun after his service in the First World War led him to question militarism and extreme nationalism.23 Many in this loosely structured group were Marxists and anarchists, and, although they did not join the German Communist Party, they believed their work should express themes revolving around class struggle. Discussions about which style and form could best communicate these subjects to the widest possible audience were central to the group’s activities. Experimenting with graphics, relief carving and oil paint, they contributed to a number of proletarian periodicals. Sander first displayed many of the photographs he was collecting for his 1929 book Face of Our Time at an exhibition of the Progressives at the Cologne Art Association in 1927. Seiwert and Hoerle admired Sander’s approach to photography as a craft and an art for they were consumed by the tactile, craft-like quality of painting in oil to which they had turned in the late 1920s. Sander did not use the newly invented Leica camera but continued to use a large-format camera, which allowed him to capture minute details of an individual face as well as the tactile surface of a canvas or a relief. As a result, Sander was the main photographer of the work of the Progressives and for a 1926 group exhibition in Moscow they used his photographs of their work as substitutes for the originals.24 A wooden relief sculpture called Lenin by a key Progressive artist Gerd Arntz, known only through Sander’s carefully detailed black and white image, was given to Sander because Arntz felt the photographer was sympathetic to the cause of the communists.25 Seiwert was among those with whom Sander was closest, and praised the representative quality of Face of Our Time in a 1930 essay, declaring that photographs would replace paintings as witnesses to the epoch for they would ‘serve as documents of our time, passed down from our era to future ones’.26

In his introduction to Face of Our Time the writer Alfred Döblin made a similar point when he praised Sander for contributing ‘superb material for the cultural, class, and economic history of the last thirty years’.27 After explaining that the portraits were not made for aesthetic or commercial reasons, Döblin asserted that the portraits were intended to be informative. Döblin called Sander’s photobook a ‘sociology’ of the changes of his epoch that revealed ‘the tensions’ between groups, and he advised comparing the photograph Working Students (fig.1), that features Sander’s son, with that of a middle class professor and his family whom the writer sardonically wrote were ‘nestling contentedly and still unsuspecting’.28 Commenting on the arrangement of images, Döblin pointed to the relationship between Sander’s sequencing of his photographs and Germany’s recent industrialisation, encouraging the reader to consider ‘the conclusion … reached by the figures from the workers’ council, the anarchists and revolutionaries’.29 The meaning of this remark has often been misconstrued since the two concluding photographs of Face of Our Time picture the unemployed.30 While the significance of Spengler’s treatise ought not to be discounted, Döblin, like Sander, was dismayed by the casualties of industrialisation. Both wanted to believe that greater equality was possible. Döblin advised consideration of a more equitable system proposed by anarcho-communist political philosophers who remained aloof from organised political parties with their dogmatic adherence to ideological rules. The figure of the revered anarchist leader of the short-lived Bavarian Republic Erich Mühsam (to whom Seiwert introduced Sander) appears in the centre of a image called Revolutionaries, and is placed about a third of the way into the book, just after Communist Leader, a portrait of Paul Fröhlich, one of the men much admired by Erich Sander, and just before Working Students.31 Following Döblin’s argument, images of these individuals could not be placed at the end of the book since they were not responsible for the unequal conditions that existed at the time. Moreover, even in the late 1920s anarchists were not only disliked by followers of Soviet communism but also by those in the centre, as well as by the right. It is not surprising then that Döblin would conclude his introduction with an open-ended comment: ‘Entire stories could be told about many of these photographs … they are raw material for writers, material that is more stimulating and more productive than many a newspaper report … Those who know how to look … will learn from these clear and powerful photographs.’32

Although Sander’s relationships with Marxists and anarchists have been relatively unexplored, it seems clear that Sander felt closest to Seiwert of all the Cologne Progressives.33 Not only did Sander hang portraits of Seiwart and Hoerle in his working room, but in the same room he also displayed Seiwert’s small oil painting The Farm Workers 1923, and in his dining room the larger painting The German Peasants’ War 1932.34 According to the curator Lynette Roth, Seiwert’s The German Peasants’ War was painted as a reminder of the farmer’s role in radicalising the work force, and both Seiwert and Sander constantly affirmed the importance of the agricultural worker, a subject not often represented by German artists associated with the German Communist Party (KPD), which viewed the industrial worker, not the farmer, as the model for change. The two Cologne friends belonged to that part of the Marxian left that included anarchists and other communally-minded utopians who chose not to be dominated by either the German or the Russian communist parties. Seiwert took the meaning of the communist logo of a hammer crossed with a sickle quite literally, and he along with most of the other Cologne Progressives viewed the form of government known as Räteregierung (with voting organised by occupation) as the most representative. Sander’s division of sections of his compendium into farmers, craftsmen, industrialists, artists, servants and redundant labourers should be seen in light of the Cologne Progressives’ belief in representation by occupation as the most inclusive political system.35 In addition, his photographs of the rural farmers of the Westerwald region that begin his 1929 photobook and People of the Twentieth Century may even be a tribute to the tradition of mutual assistance and cooperation (fundamental anarchist values) which allowed the farmers and miners of the region where Sander was born to own their land and homes during the turbulent and changing times of industrialisation.36 Unlike other rural areas in Germany, the people of Westerwald had owned the ‘mining rights and also the forestry rights’ of much of the land on which coal was discovered. Income from this land contributed to their independence and self-sufficiency, allowing them a means of self-regulation that was not found in other parts of Germany.37

Sander had faith in the power of his photography to communicate strongly and positively to the ordinary person, and like the Cologne Progressives he wanted his art to affect the lay person. In a 1931 radio lecture, while acknowledging that photography could be manipulated for evil as well as for good, Sander insisted that photography as a ‘global language’ had fewer limitations than the verbal. The latter was too abstract and required too much ‘knowledge and intellectual training in order to be understood’.38 Speaking about how a photographer could capture ‘a physiognomic portrait of the era’, Sander described a number of aspects he felt the photographer had to combine to convey the historical moment: not only the face, but also the position of the body and dates. He even expressed the possibility that political views could be represented by photography: ‘Consider, for example, the parties in a nation’s parliament; if we start with the rightwingers and move gradually towards those furthest to the left, we already have a partial physiognomic image of the country … they all carry in their physiognomy the expression of their time and the attitude of their group, and this is especially the case with particular individuals.’39 His arrangement of his work after the Second World War confirms to some degree that he continued to believe (even many years later) that his portrait photographs could impart a lesson.

However, after the war, when he began preparing the two memorial portfolios ‘The Persecuted’ and ‘Political Prisoners’, Sander appears to have been guided less by making his audience aware of class differences and more by making them aware of the horrendous injustices suffered at the hands of the Nazis by Jews, political leftists such as his son, and those his son photographed. Many of the imprisoned individuals were photographed either in prison garb or without shirts, making them seem more vulnerable upon first impression. In one head and shoulders shot of a man who has an uncanny resemblance to Erich Sander (when compared to a snapshot of Erich taken for National Socialist records of ‘criminals’), the pale upper body and face is contrasted against a darkened background (fig.8). Through this precise accentuation of dark and light, Sander changed an archival type of record to a monumental epitaph. The careful framing of the body, which cuts off the outside edges of the upper arms, forces the shoulders to appear massive, while the precisely delineated darker skin of the face allows the eyes of this inmate to stare uncompromisingly at the viewer, searing his gaze forever into our memory.40

Sander referred to archetypes, using the term Stamm (with its connotation of original roots, and tribes), to indicate the Westerwald farmers that begin his life-long project, but he did not use the Jewish type or archetype that dominated photobooks about Jews produced by experimental photographers during the Weimar period.41 Photographs such as those taken by the former Bauhaus student Moshei Vorobeichic in 1931, and by the photojournalist Tim Gidal in 1932, presented the eastern European bearded orthodox as the prototype of the authentic Jew.42 Sander also avoided the anti-Semitic stereotypes that could be seen in many essays printed by the right or even in portraits by non-communist left artists such as Otto Dix.43 Indeed, the well-clothed individuals in Sander’s ‘The Persecuted’ portfolio do not stand for any specific Jewish type. The individuals were from different economic classes and most likely from different denominations of the Jewish faith, but all appear to be assimilated in their clothing and physical appearance. While the sweater-vest and the lack of cuffs of Arnold Katz’s portrait (fig.3) may indicate a less financially secure class than the portrait of the impeccably suited Mr Oppenheim, the clothing worn by the sitters in this portfolio – men in suits with ties and women in blouses topped with pearls or other appropriate jewellery – would have been customary for passport photos at that time.

However, these details are unable to deny the affect of anxiety and vulnerability communicated by the saddened, even frightened expressions on their faces. The angle of the body betrays these feelings as much as the down-turned mouths and eyes. The neutral brown surface against which all of the faces and bodies in this portfolio are set monumentalises and even dignifies the figures in the same way that it did for the artists, musicians, architects, and writers in Face of Our Time. Many of the other individuals in the 1929 photobook were given tools to represent their occupations (the broom of the cleaning women) or were posed against backgrounds related to their work (the cellar doorway of the coalman).44 Comparing the photograph of Arnold Katz with that of Sander’s friend the writer and literary critic Dettmarr Heinrich Sarnetzki, for example, or with the Cologne Progressive artist Jankl Adler (fig.6), it is noticeable that although all of them are represented in a seated position, Sander has captured Sarnetzki actively sitting forward and Adler looking directly at the viewer while Katz slumps in the more passive position in which he has found himself. Although Katz was a small businessman – the owner of a butcher’s shop not far from Sander’s studio – Sander gave him the austere monumentality that he gave to the writer and to the artist. Despite the down-turned mouth and the bent hand about to open, Sander’s portrait conveys a humane solidity that mocks the newspaper photograph of Katz in which he is depicted being derogatorily paraded through the streets of Cologne four years earlier during a Nazi boycott of businesses owned by Jews (fig.4).45

The number of contact images that Sander printed for each sitter may not have been unusual for the taking of passport photographs at that time, but the variety of poses and the care with which he selected the most solemn, dignified image to print indicates Sander’s concern for those who commissioned the images. The numerous contact prints of the Oppenheim family reveal the number of shots and changes of position, even clothing, behind the final print.46 In the various contact prints of Mr Oppenheim, Sander photographed him from both a three-quarter view and a frontal view, choosing the three-quarter view for the final print, in which the hands are cropped and the white curtain is eliminated so that the anxiety communicated by his down-turned mouth becomes paramount. The contact sheets for Oppenheim’s wife indicate that not only did Sander capture her from both a left and right three-quarter positions, but that her arms are folded in two different ways. Most striking is a third image, which he printed, where she wears a short-sleeved printed blouse but appears against a blank wall. The portrait of the Oppenheim daughter that Sander chose to print is moving in its emphasis on her unlined freckled faced and her dark hair arranged simply behind her ear (fig.9). The light colour of the sweater visible around her neck and in the narrow stream beneath her barely open dark jacket gives a soft and delicate tone to her skin, emphasising her youthfulness. Again the neutrality of the background only serves to dignify and monumentalise the young woman even more.

Fig.10

August Sander

Unknown Nazi c.1930–1935

Gelatin silver print

232 x 164 mm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© J. Paul Getty Trust

Is it possible to differentiate a portrait of a Nazi official from a portrait in ‘The Persecuted’ portfolio, even if the former wore civilian clothing and did not have a party membership button on his lapel? Comparing a photograph of a National Socialist officer in a striped suit (fig.10) with that of Mr Oppenheim, it might be noted that the round, black-rimmed glasses and the high forehead point to similarities between the sitters.47 But it is not the older man’s grey hair or evenly creased face that differentiates him from the younger man. Upon closer inspection, the relaxed position of the younger man’s hands, his dapper suit, and the elegant studio chair framing and yet confining his body become more noticeable, as is the confident smile of someone, as Döblin remarked about another young man from an earlier time, ‘nestling contentedly’ in an armchair. It seems unlikely that Sander would have included the few photographs of Nazis in his compendium to indicate a naïve faith in the so-called goodness of all people. In response to those who question Sander’s inclusion of photographs of National Socialists in his portfolios, it might be deemed that when he took the photographs he may well have needed the income. But it could also just as well be deemed that he chose to include some of those photographs because not to use them in his survey of the multifaceted political and cultural views of the period would omit reference to the militarism and nationalism that led Germany astray. Not to have included images of this aspect of the German citizenry would have certainly been naïve.

During the war Sander returned to the Westerwald region of north-west Germany near the small village of Hagen where he was born in 1876. His photographs of rural farmers of that region, which are positioned at the beginning of Face of Our Time and People of the Twentieth Century, are vivid references to both the independence of these people and their self-regulation that made their independence possible. To describe this reference as a nostalgic celebration of a primeval past (with Aryan roots) would be to misread the nuances of history. Sander was quite aware that this region was transformed by the events of the twentieth century. Neither during the interwar years nor after the Second World War did he choose to remain in the Westerwald region. The city of Cologne was not only a place where he could earn income but it was also a place of stimulus. During the 1920s his friendships with writers and intellectuals, particularly with the artists associated with the Cologne Progressives, solidified his philosophical and artistic goals, and supported his desire for a diverse Germany, one that would include Westerwald farmers, anarchists, anarcho-communists, Jews, and other such intellectuals who remained apart from the didacticism of the German Communist Party and the Nazi Party as well. However, like the KPD Sander would have also been troubled by the problems of the underclass, particularly the unemployed. Yet even during the 1920s the unstructured politics of pacifists, anarchists and anarcho-communists along with the Socialist Party of Germany was denigrated by the KPD as well as by the right. During the Cold War years of the 1950s, with the fear of the Soviet Union, Sander may not have wanted to emphasise his earlier embrace of left anarcho-communist politics. As is well known, Sander kept revising and changing the order of each portfolio up until his death in 1964, but what is not always considered is that deciding on the arrangement of seven volumes of photographs would not have been easy for someone so committed to creating meaning for the future. His desire to relate his son’s prison photographs with his efforts to photograph persecuted Jews, so clearly rendered in the 2002 compendium, should be seen as more than just an antifascist gesture.

In a letter dated 31 December 1946 to his son’s close associate Paul Fröhlich, who had written about how many of his relatives had been killed by the National Socialists, Sander wrote that he wanted his lifetime project to ‘provide insight into our age and its people’ and to become ‘more valuable’ in the years to come.48 Döblin’s request in the introduction to Face of Our Time that readers compare portraits from different economic and cultural groups in order to focus on ‘the tensions of our time’ may have some applicability to People of the Twentieth Century as well. His concluding words urging the reader to actively engage with the photographs in the 1929 book so that they might ‘discover more about themselves and more about others’ are all the more resounding in the twenty-first century.49 With today’s awareness of cultural variations and crossovers, ‘scientific’ bases for comparisons and any sense of certainty about the universality of differences are no longer accepted, but this awareness should not be used to discredit Sander’s portraits as philosophically ‘matter-of-fact’ or politically ‘middle of the road’. It seems very unlikely that Sander felt equally about all the different representatives of German society. After the Second World War Sander may not have been as convinced by anarcho-communism, but there is no reason to believe that he radically departed from Döblin’s interpretation of his photographs as raising questions about the problems of the modern world. Resistance to doctrinaire or dogmatic instruction may have been the most significant concept Sander retained from his contact with anarchist thought. While contemplating the urgent issues of this century, it might be wise to accept Sander’s and Doblin’s invitation to participate in the process of mediation and renewal by reconsidering Sander’s works.