From the early 1990s artist Akram Zaatari (born 1966) has developed an interdisciplinary and expansive artistic practice that combines the roles of image-maker, archivist, curator and critical theorist. Whereas in the West this multi-tasking might be seen as the product of a set of pressures imposed by a ‘network capitalism’ that favours flexibility and multi-tasking, in post-civil war Lebanon it is the outcome of a context in which, until very recently, there was very little institutional support for the production and dissemination of contemporary art. In such a situation artists in Lebanon have often found themselves ‘focused on the development of structures without being an arts administrator or a curator, interested in histories without being a historian, collecting information without being a journalist’.1

Zaatari is a member and co-founder of the Arab Image Foundation (AIF), a non-profit organisation established in Beirut in 1997 to preserve, exhibit and study photographs from the Middle East, North Africa and the Arab diaspora from the nineteenth century to today. It currently holds a collection of more than 300,000 images, including negatives and prints sourced by its artist-members.2 Zaatari has undertaken numerous curatorial initiatives centering on the development of the amateur and commercial photographic practices in countries such as Egypt, Lebanon and Syria. But rather than simply using images as evidence of societies in the grips of modernisation, his AIF exhibitions – such as Mapping and Sitting (a project on the history of amateur and professional portrait photography in the Arab world conceived with artist Walid Raad) and the ongoing project Hashem El Madani: Studio Practice – have emphasised the performative role that photography plays in fashioning identity.

Zaatari discovered the photographs of Madani (whom he believes was the first to own a 35 mm camera in Saida, the artist’s birthplace) in the course of research for his 1999 AIFcuratorial project called The Vehicle: Picturing Moments of Transition in a Modernising Society. Madani captured the daily lives of those who could afford to come to his studio and of those he photographed standing or sitting in the streets in the late 1940s and 1950s. Many images in the Madani project thus seem to speak of the photographer’s role in capturing and cataloguing daily life of people in the south. To the historian, however, these images record specific chapters in pre-civil war south Lebanese history: a public fascination with the first radios and a long-held tradition of local fishing are handled with the same apparent objectivity as the influx of Palestinian refugees into south Lebanon beginning in 1948.

But Hashem El Madani: Studio Practice is not as self-evident an archive as it perhaps first appears. Madani’s Abu Jalal Dimassy and Two of his Friends Acting Out a Hold-Up c.1950s (fig.1) depicts two men in white button-down shirts and police hats pointing small pistols at a third man in a kuffiyeh (a traditional Arab headdress fashioned from a scarf). The ‘hold up’ is a performance, suggesting that the development of a specifically Palestinian iconography of armed resistance was in part mediated by the image of the anti-hero popularised in Hollywood films. A photograph of Hassan Jawhar 1968–72 (fig.2) shows a fadaiyin (resistance fighter) standing with a semi-automatic rifle, but the documentary status of the image is complicated by the realisation that the man is in Madani’s studio and that the gun may be as much of a prop as the airplane and rocking horse visible at the edge of the photograph. Deceptively factual in appearance, these images move between self-conscious displays of armed resistance and its photographic simulation. At the same time, they also lead us to consider how Zaatari’s seemingly dispassionate project of archival research is bound up with his own deep attraction to the subjects captured in these images: ‘I loved the Palestinian feda’i, my childhood mythical fighter figures, who used to give me all sorts of bullets to collect as a kid. I loved how they lived on the streets, how they slept in the fields or in vacant buildings. I loved how they smelled. I envied them for fighting for justice; I sincerely loved them’.3

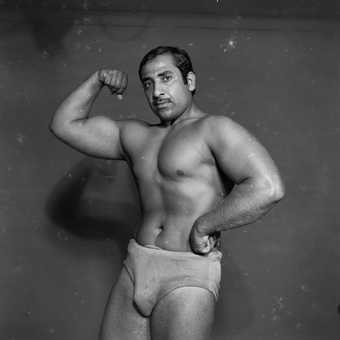

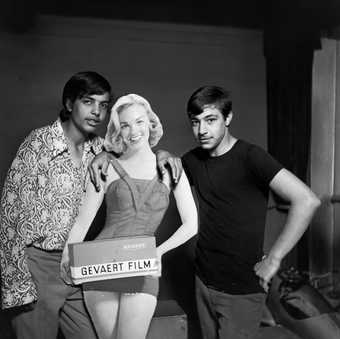

This deployment of the archive as a site of libidinal investment also animates Zaatari’s appropriation of images of weightlifters taken by Madani in the 1960s. The images of a body-builder titled Reesh (fig.3) read ambiguously when placed alongside the caption: ‘men in general used to like showing their muscles’. Similarly, in the 1966 photograph of two burly young men from the village of Aadloun who pose with and appear to share the cut-out of a curvaceous European blonde (fig.4), the display of hyperbolic masculinity is here made open to a queer gaze. Indeed, Zaatari makes it difficult to disentangle the desiring eye of the camera from his own scopophilic attachment to these figures of hyper-masculinity.

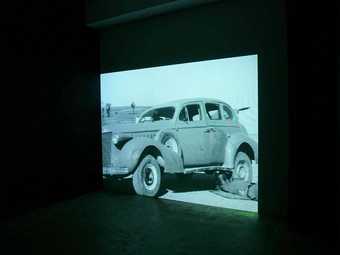

Another aspect of Zaatari’s practice that is taken up in this interview is his method of recording the everyday in times of war. This sensibility was formed in the course of living through fifteen years of war in Lebanon, watching much of it unfold in his teenage years. Frequently confined to the family apartment, Zaatari developed the precocious habit of taking notes and making photographs and radio recordings of events that were both personal and public in their significance. More than twenty years later, Zaatari would draw on this personal archive as the basis of This Day 2003 (fig.5), a video essay that uses a multi-layered and open-ended filmic language to examine the movement and obstruction of images and people in a historically divided and perpetually war-torn Middle East.

Akram Zaatari

This Day

(2003)

Tate

Specifically, This Day analyses the mobilisation of images and populations during the Israeli invasion of the West Bank in 2000–2. Zaatari places contemporary Lebanese television commercials, internet news reports, and emails sent in support of the Palestinian cause alongside a montage of the aforementioned Palestinian fighters from the Madani studio. On this occasion, however, the photographs are synched to a soundtrack of contemporaneous militaristic anthems glorifying the Arab cause. ‘During times of war songs change and images transform’, Zaatari notes by way of an intertitle that he types across the screen. Indeed, This Day insistently calls attention to the material and technological procedures through which images are mediated. This can be seen in the sequences where Zaatari trains his camera on his television set or records his own act of downloading images from the internet. Elsewhere, we see video footage sped up, frozen and slowed down as the artist works at an editing station. In making visible these techniques of consumption and post-production, Zaatari focuses attention on what is normally held out of frame or normalised through force of habit. This in itself becomes a highly political gesture in a media environment that capitalises on the apparent immediacy and transparency of the digital image.

In This Day Zaatari’s examination of images made under the pressure of successive wars and military occupations is further complicated by his engagement with another visual archive: the compilation of photographs shot by the Lebanese-Armenian photographer Manoug (some of which later appear in the Arab scholar Jibrail Jabbur’s 1988 ground-breaking study El Badou wal badiya [The Bedouins and the Desert]). Wearing white gloves, Zaatari carefully arranges original negatives and contact prints of Manoug’s photographs on a lightbox. These same images are also shown as reproductions in the Arabic and English versions of Jabbur’s book. Like other contemporary art practices that point to the uneven and contingent character of ‘the archive’ (both as a material repository and as a set of discursive practices), Zaatari’s re-use of historical documents powerfully undermines the idea that the past can be fully reconstituted on the basis of its documentary traces. As Norma Jabbur points out, her grandfather’s genealogical project was itself haunted by the sense that the traditions of Arab culture were ‘already vanishing’ under the effects of modernisation. In other words, the bedouins (a desert-dwelling Arabian ethnic group; fig.6) had become an object of Arab nationalist consciousness at the very moment when nomadic ways of life were being displaced by notions of territorial identity that were themselves a by-product of the borders imposed on the region by the European colonial powers at the beginning of the twentieth century. Tellingly, when Zaatari finally succeeds in tracking down a ‘real’ bedouin in the Syrian desert in This Day, he has trouble understanding his dialect. Eventually he discovers that the man had wandered across to this part of Syria from Saudi Arabia before the two nations existed. This stateless subject thus comes to symbolise a time and place that stands in tension with the dominant cartographic logic of the present-day Middle East.

Fig.6

Akram Zaatari

Met'eb el Maasheh, a Rwelah Bedouin from the Raja Tribe Northern Outskirts of Palmyra (Syria) 2000

© Akram Zaatari

In the process of coming to international prominence, Zaatari and his Lebanese compatriots have developed artistic practices that ask us to rethink what it means to witness, survive or indeed document a war. By unearthing historical artifacts and collecting eyewitness testimonies, Lamia Joreige, Rabih Mroué, Walid Raad and Zaatari have considered how and in whose interests the conflicts in Lebanon are imaged and narrativised. No doubt a large measure of this generation’s critical success lies in their ability to formulate a theoretical discourse that rightly questions art’s ability to register a history shaped by the trauma of sectarian violence and social unrest. Accordingly, the curator Suzanne Cotter refers to ‘the mistrust of the image as a reliable document of history’ as a defining feature of post-civil war art from Beirut.4 This critical line rightly sees art’s problematisation of representation as a necessary counter to the everyday reification of documentary practices, particularly when the latter serve as instruments of judicial evidence and journalistic truth. Yet just as there has been an increasing tendency on the part of critics to foreground the failures of representation (most especially in the work of Raad’s Atlas Group), much of the discussion of contemporary Lebanese art has tended to bracket the historical referent. Indeed, the over-emphasis placed on the instability and manipulability of visual evidence in this art often prevents a more concrete engagement with its historical sources. Granted, these histories are deeply contested and resist any search for conclusive truths, but they are not for all that outside of representation. Nor does this art’s entanglement with the mythologies and traumas of the ‘civil war’ absolve us of the ethical task of asking what kind of documentary practice might serve as the basis for a politics of truth.

With these concerns in mind, this interview, undertaken in 2011, moves chronologically through Zaatari’s major works over the last fifteen years, unpacking the fundamental problems and questions driving his practice during this period. Without privileging the artist’s intentions or biography, this exchange seeks to provide readers with a framework for understanding the complex political and historical references that inform Zaatari’s art. One of the main challenges here was to shed some light on the fate of the predominantly leftist resistance movements that operated in south Lebanon prior to and following the Israeli withdrawal in 2000. This history forms the subtext of one of Zaatari’s earliest experiments in documentary video, All Is Well on the Border Front, which he made in 1997 while he was still working in Lebanese television. If the testimonies gathered by Zaatari serve to give form to a dimension of life under occupation that has been censored from the dominant narratives of heroic resistance, his work crucially refrains from speaking on behalf of the oppressed. Moreover, as this interview makes clear, All Is Well complicates assumptions pertaining to documentary practices as being rooted in structures of confession and empathetic witnessing.

While offering much-needed insight into local histories that are unknown to audiences outside of Lebanon, this dialogue also attempts to consider how Zaatari’s examination of sex and sexuality link up with recent critical theorisations of queer desire and gay liberation in non-Western cultures. For the most part, Zaatari’s research on this topic has been neatly separated from his work on war. By contrast, this interview serves to suggest that these two strands of his practice might be mutually imbricated.

Fig.7

Akram Zaatari

Sketched Map of Main Roads Around Lebanese-Israeli Border 2012

© Akram Zaatari

Chad Elias:

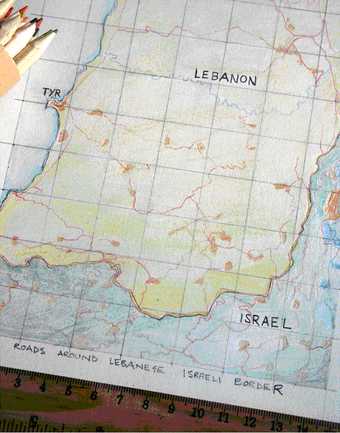

In 1997 you started to conduct research on the southern occupied zone in Lebanon (fig.7). The immediate aim was to understand the economic and political factors that led to the Israeli occupation of 12% of Lebanon’s territory, with the pretext of providing security to the north of Israel.5

A number of questions lurk in the background. How was Israel able to convince thousands of Lebanese people to work for it? How was this consent manufactured in ideological terms? Who left, and where did they go? Who stayed, and under what conditions? What strategies did the local populations of the south develop to resist occupation? I would like to know what your own views on the occupation were back then (in the mid–1990s) and how they changed over the course of your research project. In other words, did your research lead you to reassess some of your own views about ‘the south’?

Akram Zaatari:

The most important thing that I learnt is that south Lebanon’s cultural, economic, and social natural extension used to be the Galilee, in Palestine, and that a major change happened in south Lebanon after the closure of the Lebanese border with Israel in 1948. It was an irreversible event. From 1948 onwards, south Lebanon could not establish equivalent ties with the rest of Lebanon. It has become like a mutilated organ. This is very specific to the area of Bint Jbeil for example.6

And it is why what is often referred to as Lebanon’s indifference, with regards to the conditions, the occupation, and escalation of the situation in south Lebanon, finds roots in that context.

On the other hand, Israel has been obsessed with expansion since its creation. If you look at Israel’s territory in 1948, it is certainly not that of today. Ironically, Israel justifies its continuous occupation of more land in Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria as ‘defence’ and even calls its army a ‘defence force’. As an occupier on the ground, Israel used different strategies in Lebanon than in the Golan, for example, or in the occupied Palestinian territories. That was due to many factors, mainly the creation of the Lebanese resistance in 1982.7 My convictions with regard to Israel did not change while working on this project, but the understanding of mechanisms of governing an area of occupation became clearer and I could start seeing the nuances, as opposed to a polarised image of occupiers and occupied.

The singularity of Israel’s occupation of Lebanon was its creation of the SLA, an army made of Lebanese individuals at the service of Israel’s interest.8 Before starting my research, such an idea of a pro-Israel Lebanese army was ambiguous, but after talking to so many people from the south, I was able to get it. The presence of the Lebanese army in south Lebanon has always been a bland one. Like the country, the army was divided vis-à-vis the armed Palestinian presence, and Israel came to widen this division, manipulating an existing schism, a cultural and a political one.

So my interest after making All Is Well was to understand the fragility of Lebanon’s political and cultural landscape, fertile and receptive to Israel’s ‘defence’ project. How Israel was able to do it is an interesting observation. Israel never closed the border between the occupied south Lebanon and the rest of the country, but made it really difficult for people to go in and out. It made it more and more difficult for villagers to market their farm products outside the region and opened the market of south Lebanon for Israeli products. In other terms, Israel was strangling the economy of the south, pushing its population either to leave the area toward Beirut or ‘bend’ and therefore enroll or collaborate with the SLA, and therefore enjoy benefits. Among these benefits could be allowing one or more members of the family to work in Israel for a relatively high salary. It was enough that one member of the family served in the SLA to open the door for other members to work in Israel. I still do not know why Israel did not give anyone from Lebanon Israeli citizenship like it did in the Golan, or like in the unique case of al-Ghajar, which is still a divided village at the Lebanon-Israel border. I think the area was too big to depopulate completely, like what has been done in the Shebaa farms, but at the same time too big to swallow into Israel.

To sum things up for you, I learned that Israel occupied south Lebanon because it took advantage of the country’s division over the presence and rising power of the Palestinian armed struggle, and exploited Lebanon’s diversity of ideologies and political currents, to its advantage. Furthermore, I understood how certain southern suburbs of Beirut were formed gradually, with waves of displacement from south Lebanon.

Chad Elias:

All Is Well operates as a critique of the dominant images of resistance that were circulated by Hezbollah in the Lebanese media in the 1990s.9

Against these images of mobilisation, you document the plight of people who have been left out of the official narratives of liberation. Two names recur in All Is Well. There is Nabih Awada, who had been imprisoned in Askalan since 1988.10

Awada, who composed moving letters to his mother under the name of Neruda, was still in prison when you made the film. There is also Mohammad Assaf, who has been transformed into a cult figure – for a generation – after he succeeded to escape from Khiam with one other prisoner.11

At the time you made the video, he had left for Germany, and no one knew his whereabouts, not even his family. In many ways, the main protagonist of the video is Assaf. What attracted you to his story?

Akram Zaatari:

It was fascinating to hear that someone succeeded in escaping from prison because he had been obsessed with a film, The Great Escape (1963). It was very much unlike the image one got of a resistance fighter to be fond of films. For me, it was such a poetic idea to entertain. On another level, some of the stories I gathered about him were a bit out of sync, which is clear in the video. Not that I cared so much for accuracy, or historical precision, but these different narratives meant to me that at the time when I did my research, Mohammad Assaf’s story had already transformed – in the collective imagination of the people who knew him – from a historical narrative, into an mythical one. He had already become a hero. The fact the he had disappeared, and the fact that even his family did not give information about his whereabouts, accelerated his mythologisation.

Chad Elias:

In the final analysis, your work refrains from presenting Assaf as a hero. Indeed, I think All Is Well is actually quite critical of the Lebanese left. It suggests that the reasons for their failure are not simply due to the divisive effects of the occupation but also a byproduct of the rigid ideological structure of these parties.

Akram Zaatari:

I believe my video is more critical of dogma within resistance in the first place, and on another level of the Islamisation of resistance. The Lebanese left was not made of one dominant party, which was a good thing about it. There was the Communist Party, the Labour Party, the Popular Democratic Party, the Progressive Socialist Party etc. Those parties used to have a fine-grained composition that reflected the religious and political diversity of the country. But on the other hand this transformed the left into a fragile body, easily breakable. In the countries where the left became the ruling power, such as in Syria for example, or even in Egypt under Nasser, the left was not defeated.12

However, the party that won crushed all the other voices within the left. So the price of ensuring the life of the ruling party was to silence opposition even from within the party itself, which gradually transformed it into a dictatorship.

Between defeat and ruling for eternity, I prefer defeat. Compared to that model, the left in Lebanon was progressive, diverse, democratic, too weak to rule by itself, which led indirectly to its withdrawal from the political scene – what you call defeat. Why not? Ideologies are not made to live forever. But, my critique of secular resistance in Lebanon is that it was dogmatic, on all levels. Although it claimed an educative, formative, and progressive mission, in fact the left always propagated obsolete concepts of citizenship, freedom, and revolution to recruit from poor and uneducated communities.

The sad story about the left in Lebanon, and that makes me and other intellectuals of my generation sympathise with it, is that it was defeated once by the Israelis and once by Hezbollah.13 But when one looks closely – as much as one is allowed to get close to Hezbollah – one notices that its dogmatic structure is not different from that of the former left. What is different is that with Hezbollah, diversity of opinions is not tolerated within the party, and transparency is blocked with the pretext of security. This is why All Is Well looked cautiously at the rising power of Hezbollah and its monopolising resistance, and is also why it ends with a six-year-old boy, standing on a plastic chair in the middle of his school’s yard, reciting a speech by one of Hezbollah’s leaders (fig.8).

![Akram Zaatari Still from Al Shareet bi khayeer [All is Well on the Border Front] 1997 TP19 LIMITED](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/fig3_still_from_al_shareet_bi_khayeer_0.width-340.jpg)

Fig.8

Akram Zaatari

Still from Al Shareet bi khayeer [All is Well on the Border Front] 1997

Video

43 min

© Akram Zaatari

Fig.9

Akram Zaatari

Untitled 2007

Mini Album. Pages 6–7. An explosion after an air-raid targeted a Palestinian base in Mar Elias hill. Looking from the balcony to the south, 6 June 1982

© Akram Zaatari

Chad Elias:

Can I ask you about the Arabic title of this video, Al Shareet Bi-Khayr? There is a lovely play on words that is unfortunately lost in translation. In Arabic, the word ‘al shareet’ quite literally means ‘cordon’ – the occupied zone was commonly known as the ‘border security cordon’ – but is also means ‘tape’, more specifically in this case, the video tape. The expression ‘all is well on the border’ is one that was inspired by Nabih Awada’s (Neruda’s) optimistic tone, which dominates his letters. Why did you single out this phrase?

Akram Zaatari:

I liked the overlaps of meaning in the term, like the overlap between the escape of a political prisoner and his passion for a movie like The Great Escape. I also like the emotional tone that made Nabih Awada (Neruda) ease his mother’s anxiety, assuring her that all was well in prison. In fact, the expression ‘all is well’ sums up the complexity of recounting stories of detention, stories of severe traumatic experiences. My video is about that. It is about how inevitable it was for those stories, when told, to become mediations.

Chad Elias:

Your representation of the failed leftist resistance in the south is significant because it challenges existing conceptions of the history of the region as one of triumphant liberation, and because it departs from a politically engaged model of documentary representation that claims to give a voice for people with no voice. You were very careful not to represent Awada and Assaf as victims or objects of pity. Nonetheless, is there a space for empathy and identification in your work?

Akram Zaatari:

I do not believe you can make a work about people you do not empathise with. Otherwise why would you dedicate that much time to them? I was moved by Awada’s letters to his mother, and by the stories his family told me about him. In fact, I truly believe that Nabih has totally and easily integrated into the Lebanese society after ten years of imprisonment in Israel thanks to his loving family. I loved him, and desired the figure of the resistance fighter that I could not claim with my middle-class background and education. At sixteen, I took pictures of Israeli air raids from the balcony of our house in Saida (figs.9 and 10); Nabih had already done six or eight operations and gone to prison at this age. His itinerary fascinated me. I knew much less about Mohammad Assaf, and his family did not help much in giving any information about him, but this mythical figure that he was, was indeed one to explore further.

Fig.10

Akram Zaatari

Saida June 6, 1982 2009

Composite digital image

Lamda print

1270 x 2500 mm

Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir Semler Gallery © Akram Zaatari

Chad Elias:

When you made All Is Well, the occupied border zone was barred to all Lebanese citizens except those born in the territory. You could only go to the parallel geography to which inhabitants of the occupied zone have been displaced and relocated: the southern suburbs of Beirut. What kind of space are we talking about here? Are there ways in which these communities can develop a sense of identity that is not rooted in an idealised vision of their home village in the south?

Akram Zaatari:

People displaced from their villages in south Lebanon lived mostly in the same neighbourhood. In order to preserve ties to their place of origin they recreated a set of social ties in a different geography. Your neighbour in the village became also your neighbour in Beirut. It was, I believe, a way to keep intact the social structures of their village of origin, and to assimilate more easily to an urban environment that threatened to strip them of their communal histories.

Chad Elias:

In one memorable scene, you tape a group of students reading essays that you had asked them to compose on their parents’ home village of Hubbariyeh. A young boy passionately describes the natural beauty of the landscape, proudly proclaiming ‘its glorious history full of jihad and heroism and of massacres’. Here you seem to be showing us how the children of the occupation are formed as subjects of ideology. Their very sense of who they are is linked to a mythical place that they know only through the stories, slogans, and images handed down to them from their parents and authorised in Hezbollah’s discourse of resistance. It reminds me of a scene in Jean-Luc Godard’s 1976 film Ici et Ailleurs where the young Palestinian girl in fatigues is reciting a poem by Mahmoud Darwish called I Shall Resist amid the ruins of Karame.

Akram Zaatari:

There are two levels at work in the scene you mention. One is inspired by Godard’s film Ici et Ailleurs, specifically the images of the boy reciting a poem that he does not understand, in a pompous theatrical performance. Godard uses this performance to comment on the form in which the discourse of the Palestinian resistance presented itself, and how it used people, children, women, and made them mediators of its discourse, or even that dogma. Ici et Ailleurs suggests that resistance does damage to its own image when it portrays itself as unquestionable dogma and when it tries to dictate its popular base, how to think and what to say and what not to. Godard concludes at the end of his film that one needs to ‘reduce the loud volume’ in order to see. I take this to mean that one has to unmake the discourse of resistance in order to communicate its ‘just’ cause in other less pompous ways. Thus, as opposed to a socially engaged mode of documentary that claims to speak to or on behalf of the Other, Godard sets out to disrupt the assignment of clearly marked speaking positions beginning with those structures that make possible his own utterances. I wanted All Is Well to have this self-critical tone. However, there is an affective dimension to my video that I think is lacking in Godard’s work, since he remains much more distant from his subjects. I like to allow myself to be moved, and then to take a distance from my emotions. The children’s essays in All Is Well are moving because they communicate the feeling of loss despite the fact they are not speaking in their own words. Their recital of those texts is so movingly human.

Chad Elias:

I was intrigued by the numerous distancing devices that you used in All Is Well. The rewinding of footage (fig.11) and the use of text serve not only to impede our reading of the images but also to suggest your idea of the ‘shareet’ as a space of ‘interference’ (a term that in electronics refers to the obstruction of clear reception of broadcast signals). What interested me most was the mediating role that scripting plays in this work. At one point you show one actor reading from a teleprompter. This is followed by a sequence in which we see the actor who plays a prisoner reading and rehearsing the script while he is driving a car (fig.12). Your voice can be heard off-screen directing his reading of the script. What we took to be a spontaneous testimony is shown to be a highly rehearsed and pre-scripted performance. The presence of the script serves to question the assumption that the work can provide direct and immediate access to these individuals or to the experience of occupation and imprisonment. Beyond your desire to deconstruct the conventions of documentary representation, what led you to use actors in this way?

![Akram Zaatari Still from Al Shareet bi khayeer [All is Well on the Border Front] 1997](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/fig6_still_from_al_shareet_bi_khayeer_all_is_w.width-340.jpg)

Fig.11

Akram Zaatari

Still from Al Shareet bi khayeer [All is Well on the Border Front] 1997

Video

43 min

© Akram Zaatari

![Still from Al Shareet bi khayeer [All is Well on the Border Front] 1997](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/fig7_still_from_al_shareet_bi_khayeer_all_is_w.width-340_74V0wXk.jpg)

Fig.12

Akram Zaatari

Still from Al Shareet bi khayeer [All is Well on the Border Front] 1997

Video

43 min

© Akram Zaatari

Akram Zaatari:

The mid–1990s were years when everyone in the political landscape in Lebanon talked about the cause of the detainees without touching on very essential issues. I used to work at Future Television, which is the television channel that belonged to former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri.14

That channel was very much engaged in the causes of south Lebanon, including its occupation and the issues of prisoners. Former prisoners were interviewed on nearly every television station, but these testimonies only reproduced the pompous narratives of the resistance, which served in the end to legitimise someone else’s agenda, be that of the political party, or the media outlets that act as their self-proclaimed mouthpieces. No one was allowed to speak about the very personal defeat that they had experienced in detention. It was always framed as a sacrifice done for the greater cause of the resistance. In reality, many of these men were burdened with long-term medical and psychological problems. Most of them left prison with absolutely no skills in anything and had to beg for a job etc. Yet contrary to what you heard them saying on television, I discovered that they had great stories to tell, disturbing and confusing stories. I realised how much of an emotional decision it was for them to join the resistance and how unplanned and quickly it happened. I wanted the video to carry this emotional mark, yet establish a distance that I saw necessary in seeing how those emotions were being consumed in the daily discourse of the resistance.

Chad Elias:

All Is Well is part of a long line of films and videos made about south Lebanon. Maroun Baghdadi’s The South is Fine, How About You? (1976), Walid Raad and Jayce Saloum’s Up to the South (1993), and Mohammad Soueid’s South (1997) are all important precedents for your work. How would you describe the impact of these works on your own thinking as an artist invested in the political potential of video?

Akram Zaatari:

The films that were made in the 1990s in Beirut had distance to the past of the war and engaged in a different set of questions, particularly the question of representation. The films made in the 1970s and 1980s seemed part of history to our eyes in the 1990s. I did not relate much to Maroun Baghdadi, but related more to the poetry and critical sense in the documentaries of the Syrian filmmakers Omar Amiralay and Mohammad Malas, who I believe made the most critical and poetic works on what was going on in Lebanon in the 1980s (Massaibou qawmin and Al-Manam). Frankly, I think their work aged quite nicely without losing its critical power. And that is rare to find in the works of Lebanese filmmakers such as Randa Chahhal, Jocelyne Saab, Jean Chamoun, and Maroun Baghdadi, who were caught in the language of direct cinema.

The 1990s were different. I was already very close to Mohammad Soueid, and his writings and his videos of the early 1990s fascinated me. We did a work each on the south, almost in the same year. His work South was finished almost a month after I finished All Is Well. I was less interested in the approach of Jayce Salloum and Walid Raad, although I give them the credit of being able to travel to the occupied area and film there, even in a clandestine way.

Fig.13

Akram Zaatari, still from How I Love You 2001

© Akram Zaatari

Chad Elias:

How I Love You 2001 (fig.13) documents homosocial and homosexual relations among a small group of gay men in Lebanon at a particular point in time. It seems to me that this video was concerned not only with the legal prohibitions on homosexuality, but also with social pressures placed on men who identify as ‘gay’ on a personal level but who are not able to claim a public dimension to their identity. You manage to capture the coded language that these men use to express their desires within a deeply homophobic society. One example of this is the man who transformed the lyrics of the Fayrouz song ana Habbaytak (I Loved You) to ana had baytak (I Am Near Your House or, more idiomatically, I Am Near You) to address his lover.15

What was the main objective of this video? What problems did you face in making it? Can you tell us more about the social dynamics of the gay community in Lebanon? What do you think defines the specificity of this scene relative to other marginal gay communities?

Akram Zaatari:

In 1997 I made the video entitled Crazy of You (Majnounak) in which I interviewed young men about their sexual encounters with women. Since then I had always wanted to make another video documenting different sexual practices. In Crazy of You the young men were so proud of being able to ‘conquer’ young women, even sometimes by tricking them into sex. Their stories were so similar, as if they were trying hard to get closest to a common fantasy ideal. I am saying this because sometimes I felt their stories were pure imagination. I wondered if they had sexual encounters with men, and how they would hide it through this language of heterosexual conquest. This is how the idea of the film was born. I did not want to make a militant film but one that records the experiences and the practices of gay men. Although gay behavior seems quite accepted, at least socially in the night scene in Beirut, it is still not widely accepted in Lebanese society, and it is still punished by the law. So I wanted to make a film where the main question is how to testify, how to speak when testimony or speaking can lead to criminalisation of the speaker. So if you do not look at the image, in other words if you are not reminded by the blurring of the image that these testimonies could get the subjects into trouble, what comes across is the normality, the banality of their day-to-day lives. There is a banality with which subjects tell their sexual encounters. They do not try to victimise themselves, nor do they try to provoke social norms. Yet, in what they say, there is pride in telling stories that might seem banal, especially to people from Western nations. Yet the blurring of the image makes the document tied to the social and legal constraints of Lebanon. So this film is about this double aspect of constructing a multilayered document. The question of coded language is inevitable in any relationship. When you’re close to someone, you develop your own language with him or her, and this is how ‘ana Habbaytak’ became ‘ana had baytak’. I see it more as a code between two, a private discourse, as opposed to a code between two in a public space. It says more about their affection than about their communication in public.

Chad Elias:

How I Love You differs sharply from your subsequent curatorial project on ‘sex practices’ for Home Works IV in 2008.16

If the former was concerned with the discourse of sex and sexuality the latter was motivated by a desire to avoid language and metaphor. Is this what led you to the work of William E. Jones?17

Akram Zaatari:

I belong to a reality that does not allow me – even if I want to – to present explicit sex in my films. And I am not a provocateur, in the sense that I like it better when my work indirectly reflects the social constructs that surround it. So this is one of the reasons why I wanted to make the sex programme in Beirut. In a way I was almost saying ‘we cannot do it, OK, so let’s see the work of others who could do it elsewhere’. I encountered the work of William E. Jones through Stuart Comer (Film Curator, Tate Modern). And indeed, I was highly impressed with this coherent body of work mostly centered on gay pornography, yet without showing any graphic pornographic images. I ended up presenting Jones’s work in a separate session on its own as part of the ‘Let It Be’ programme in Beirut.18

I thought it is indeed important to see them next to more directly graphic representations. Despite the fact that there is nothing pornographic in Jones’s films, I see them glowing with ‘sex’. So to answer your question about How I Love You: yes, the work differs from all that I presented in the ‘Let It Be’ programme, yet the ideas behind it are much the same. There is also eight years between them, so that alone accounts for the differences between them.

Chad Elias:

How I Love You left me wondering what form the struggles for gay rights would have to take in Lebanon. Recently, Arab scholar Joseph Massad has challenged the assumption that the Arab world has not yet caught up with the Western model of ‘liberatory’ homosexuality. He argues that organisations that aim to ‘liberate Arab and Muslim “gays and lesbians” from the oppression under which they allegedly live by transforming them from practitioners of same-sex contact into subjects who identify as homosexual and gay’ are in fact imposing a Western model of homosexuality.19

While there are certainly problems with Massad’s assertion that the rare public expressions of gay identity in Arab countries are the product of a Western sexual epistemology, he rightly challenges the uncritical adoption of a gay politics oriented around coming out of the closet. What paths have the struggles for gay rights taken in Lebanon over the last two decades? What advances, if any, have been made and how do you see art playing a role in the study and representation of Arab homosexual practices?

Akram Zaatari:

International queer advocacy groups aim to fight the openly homophobic laws and discourses that are still prevalent in many Arab countries. Yet for the most part, gay and lesbians in the Arab world resist oppression on a personal level, and their stories do not necessarily reach the public sphere. Thousands of people have intervened in families and in the workplace, defending homosexual individuals from injustice, and many have succeeded. I think that recent local institutional efforts are only a culmination of individual efforts that were born in Lebanon in a sporadic way since the 1990s, including maybe the making of How I Love You. I acknowledge the role of international institutions in funding these initiatives and helping them to organise, but I do not understand why such support is sometimes seen with paranoia, suspicion or even seen as a threat. A threat to what? To past values? To religious or social values? To the way Arab cultures used to think and carry their sexual lives in the past? And why should we think that those past practices are necessarily better or healthier than other gay practices coming from ‘the West’? The struggle for human rights is a global struggle now, but it becomes quite complicated for gays and lesbians in this part of the world. I would accept that one cannot simply impose a Western paradigm of sexual emancipation onto gay men and women in the Arab world. Indeed, the assumption that ‘freedom’ necessarily means being openly gay cannot be taken for granted.

However, I am wary of the ways in which local contingencies can feed into a reductive relativism that make cross-cultural and transnational alliances impossible. Without assuming a universal norm, one also has to be critical of Arab states and societies which have allowed very little tolerance of difference to a heterosexual norm propagated through religions and shared, visible social practices. They could not cope with many of the changes that have stemmed from globalisation, just as they could not deal with the institutionalisation of human and sexual relationships in civil societies. Instead of accommodating for homosexual behaviour and finding ways of granting it social recognition, most Arab cultures first denied its existence, and condemned it, and then considered it an abnormality or a Western trend whenever a homosexual story became public. In other words, they were too protective of dominant religious and social values until the issue became indeed a public one, a pressing one, a human rights one, and once that happens, of course international organisations will rush to intervene, to ‘rescue’, to ‘liberate’. No matter how one may critique this interference, it remains a blessing, frankly, compared with retrograde laws and inhuman treatment of homosexuals that persist in Arab nations.

Massad fails to see the nuances in the daily struggles of many gays and lesbians. As a result, he falls into stereotyping and generalising, and he misses the fact that the opposition between West and East is today way more complex than the binary he sets up. In other words, the Muslim world he is talking about is not at all what he thinks it is I am afraid. Furthermore, the gay rights campaigns that Massad is criticising have in some instances had very positive effects. In 2011 Lebanon’s minister of the interior publicly condemned an incident of gay bashing. In the same year a judge from the town of Batroun acquitted two men after they were put on trial for having sex, setting an important precedent in the legislative system. This happened despite the fact that the Lebanese penal code still considers homosexuality as an act against nature and punishes offenders with prison sentences that range between a month and a year. Yet there is a long way for the struggle to go, primarily in the realm of public education.

Chad Elias:

Shot in Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan, This Day (2003) is a work that employs figures of transportation (the camel, the car, and the aeroplane) and technologies that involve the transposition of vision itself (photography, video, and the internet) to examine the circulation of images amid long-standing geo-political divisions in the Middle East. On the one hand, This Day could be seen as an attempt to draw connections between disparate geographies and the histories associated with them. On the other hand, the video shows that the same technologies that allow for the movement of images across borders also reinforce the reality of spatial distance and temporal rupture. Was it this double aspect (proximity and separation) of the image that you set out to foreground in the video?

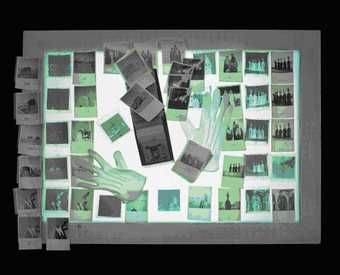

Fig.14

Akram Zaatari

The Desert Panorama 2007

16 negative sheets, 33 contact prints, a tray of negatives and contact prints with white cotton gloves on light table. The photographs were taken in the 1950s.

© Akram Zaatari

Akram Zaatari:

This Day was an artist’s commission meant to address the production and diffusion of images in the Middle East, meaning Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Palestine/Israel. So geography was in the project from the beginning. I am particularly interested in looking at the Middle East as an important part of the former Ottoman Empire, and as a region that never recovered from colonial partitioning. This Day is structured around a set of oppositions. On one hand, there is the desert, and on the other is the city. Movement/stillness. Photography and video. Physical geography/mental geography. Nomadism/nation states such as Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Israel. Yesterday/today. The camel as the ship of the desert/the car as the vehicle in the city. Parallel to this are the modes of disseminating information, photographs, texts, such as writing a journal, writing an email as a predecessor of a blog, sending an image as an attachment to an email, as opposed to graffiti, political posters, flyers, etc. On top of all this, the documentary form, and the poetry and plasticity of working alone in a photographic archive (fig.14).

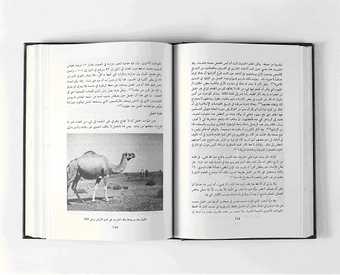

Fig.15

Akram Zaatari

Untitled 2007

Photograph of Jibrail Jabbur’s book el Badou wal Badia (The Bedouins and the Desert), p185, 1986

© Akram Zaatari

The caption below the illustration reads: “The camels out in the desert pasturing.”

Chad Elias:

One of the main strands that runs through the video is the collection of photographs of the Syrian desert taken by Jibrail Jabbur, a professor of Arabic literature and Semitic Studies at the American University of Beirut, and the Lebanese-Armenian photographer Manoug in the 1950s. These photographs formed an important component of Jabbur’s ground-breaking study, The Bedouins and the Desert: Aspects of Nomadic Life in the Arab East (1995; fig.15). Jabbur offers a ‘wide-ranging account of traditional Bedouin life in the Arab east that extends from desert wildlife and lore on the camel to the marriage customs and the history of the enigmatic tribe of Slayb’.20

What attracted you to Jabbur’s study?

Akram Zaatari:

Very often people misread my interest in Jabbur as an attempt to recover the origins of Arab culture (symbolised in the vanishing figure of the Bedouin), but this was not my intention. I was interested in Jabbur because he was the earliest example of an Arab scholar who decided to document his culture photographically. In This Day I set out to film the same locations and people that he photographed in the desert. The idea was not to reconstitute his itinerary but in fact to show that the conditions that defined Arab culture for Jabbur in the 1950s are no longer accessible to me. You see this when I try talking to one of the older Raja Bedouins only to discover that I could not understand what he was saying. His language, customs, and rituals are not accessible to me anymore. So tied to this disjuncture between past and present is the question of translation within and across media. The images taken by Manoug are hybrid objects, neither fully Arab nor completely Western either. This hybridity is captured in a photograph of Jabbur in the desert standing next to a broken down jeep. The jeep, a Western vehicle, breaks down in the desert landscape, a loaded symbol of the Arab east (fig.16). I was interested in this split optic that resulted from the encounters between European and Arab cultures. Parallel to this there is an investigation of older geographies, namely how the collapse of the Ottoman Empire led to a re-mapping of the region. My fascination with nomadism and Bedouin culture was about considering whether these pre-modern spatial practices might provide an alternative to the still prevailing logic of partitioning and cartographic containment.

Fig.16

Akram Zaatari

The Desert Panorama 2009

Detail of a composite image made with seven photographs taken by Jibrail Jabbur and Manoug in the Syrian desert in the 1950s

© Akram Zaatari

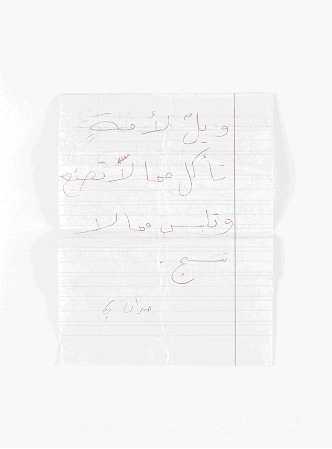

Fig.17

Akram Zaatari

Letter from a Time of Peace 2007

Letter by Ali Hashisho that was buried inside a mortar case. Translation: Pity the nation that eats bread it does not harvest and that wears cloth it does not weave (Khalil Girban).

© Akram Zaatari

Chad Elias:

Can you tell me about the origins of your video In This House (2005)? What led you to undertake this project?

Akram Zaatari:

I was doing research on personal documents that people keep, particularly in times of war. After I worked on This Day, and after I examined how growing up in the middle of an invasion changed my relationship to recording daily routines, I thought about looking for a parallel to my own documentary practices. I contacted a Saida-based photojournalist of my age named Ali Hashisho thinking that he might be able to provide access to some stories that came out of his work. I did not expect that he would be that person I was looking for. He is from the same city as me, Saida. He is almost the same age. We lived through the same war from different class positions. Still, he took notes in diaries that looked like mine. He was also documenting the war with a camera, learning photography in his adolescence much as I had done. I ended up a video-maker and artist. He ended up a press photographer.

Following the Israeli withdrawal from Saida in 1985, the village of Ain el Mir became the frontline. As a result, the residents of the formerly occupied village were forced to leave as the battle lines were redrawn. As a member of the leftist resistance allied with the Democratic Popular Party, Ali occupied a house in the village owned by the Dagher family. When the war ended in 1991, Ali wrote a letter to them justifying his occupation there and welcoming them back home. He placed the letter (fig.17) inside the empty case of a B-10, 82 mm mortar (fig.18), and buried it in the garden. When I asked Ali about this letter, he told me that it should still be buried in the garden, two steps away from the right corner of the house. On12 October 2002 I headed to Ain el Mir to meet this family. It was relatively easy to locate the house, given the precision of Ali’s references. After knocking at the door I introduced myself as a documentary filmmaker working on the subject of war in the region. At first the patriarch of the family, Charbel, did not believe I was a filmmaker and was extremely suspicious of my motives. I was actually trying to hide the main story from him because I wanted to film his reaction. I wanted him to make the discovery. I was also scared that we would dig and not find anything. So there really is a tension or suspense that is attached to this excavation which I think gives the video its narrative drive.

Fig.18

Akram Zaatari

Earth of Endless Secrets 2007

B-10 82 mm mortar case that held Ali Hashisho’s letter for eleven years

Buried in 1991 and excavated in 2002

© Akram Zaatari

Chad Elias:

What contact did Ali have with the Dagher family? Why does not he participate in the excavation?

Akram Zaatari:

From the beginning I sensed that Ali was not really keen on going back to the house. Even though he lives very close to the house and drives by it quite regularly, he was resistant to the idea of having any contact with the family living there. The Charbel family also refused to let Ali enter the house. These are people with incompatible political ideologies, different sensitivities and ways of thinking, so there could not be any real room for dialogue even though they came from the same area and shared a history of displacement and occupation. Ali wanted to keep the letter preserved for an indefinite time, but time ended up being me. Ali only became directly involved when we were having trouble locating the letter in the ground. Interestingly, after the digging was over, the representative of the Lebanese Army who supervised the excavation said to me: ‘did you notice that the family would have preferred not to find the letter’? The family could not live in peace knowing that the letter was there buried in their garden but once they read Ali’s message they also had to confront and maybe revisit their own prejudices. They did not want to accept the idea that a so-called freedom fighter (whom they considered a militiaman) could express these sentiments. The content of the letter is in fact compassionate and literate. In it, Ali affirms his belief in the eventual triumph of the poor and the abolition of man’s exploitation of man. He also states that he is against forced displacement and violating people’s dignities, assuring the owners that he did his best to protect the property. To this end, he quotes a line from a poem by Khalil Gibran: ‘Pity the nation that eats bread it does not harvest and wears cloth it does not weave’.

Chad Elias:

The video makes mention of the Christian families who lived in the south under Israeli occupation. We are told that they were interrogated for possible collaboration with the enemy. Could you talk more about this process? How exactly is surveillance enforced in this village? Does it function to re-inscribe old sectarian divisions or does it have a different effect?

Akram Zaatari:

What you are talking about happened after the Israeli withdrawal. Not only Christians collaborated with the Israelis, by the way. The Shia and Druze were also a major part of the SLA. After the Israeli withdrawal from south Lebanon in 2000, Walid Joumblat and Hezbollah reached an agreement with the Lebanese army and the Maronite patriarch to protect everybody.21

They were aware of the dangers of people seeking retribution from former members and collaborators of the SLA. Yes, most SLA members were interrogated before they were released or before they got sentenced. Many of them are still serving sentences in prison. This happened to Christians, Shia, and Druze. But the difference between Christians and other former SLA is that Christians from the south feared that they did not have a strong national leader who could at least ensure them a reduced sentence. This is why most of those who fled into Israel were Christians. They were completely desperate. They started to come back in the few months that followed the Israeli withdrawal after they saw that the SLA members who stayed were not killed. Those were certainly interrogated because they were suspected of being recruited by the Israeli intelligence.

Concerning surveillance in the villages east of Saida: in 2002, the Lebanese army was not yet officially present in the formerly occupied areas. The army did not want to have an official military presence in that area, even after the Israeli withdrawal. It always refused to act as the police for the Israeli border. They did not want to be blamed for any operation by Hezbollah. Having an official presence in that area meant stopping Hezbollah from carrying out military operations. This was something that was unanimously refused by everyone in Lebanon including the Syrians. It was only in 2005, after the Syrian withdrawal from Lebanon, that voices started to call for sending the Lebanese army to the south. But it was possible only in 2006, after the July war, that the Lebanese army based itself in the south.22 So before that, all areas were surveyed by different intelligence groups, namely the army’s intelligence and the state security (known as Amn Dawleh); the police, referred to as Darak; and, wherever Hezbollah existed, Hezbollah informants. So this surveillance has nothing to do with old sectarian problems. In this region there was no overtly sectarian violence like in the Chouf for example, after the Israeli withdrawal in 1983.

Chad Elias:

I am interested in the social dynamics of witnessing in this video. Although they seem apprehensive, the neighbours seem to derive pleasure from their involvement in the excavation. Their role was not simply as bystanders, but as active participants. Could you talk more about the sense of paranoia within this village? How does the ‘geography of fear’ that you refer to in your writings specifically manifest itself in the video?

Akram Zaatari:

The family did not accept to be filmed for reasons I did not understand. No matter how I wanted to assure them that they would be secure, they were so suspicious. They insisted that they had no political cover that would protect them from harm that a film might cause. In the beginning, as I say in the video, they categorically refused to let me dig. But after a while they started to use the story to prove they are good, obeying citizens. And this is how Charbel was in contact with all the different security officials in the region, telling them about what he thought was a juicy story: ‘something hidden in my garden, maybe explosives, maybe looted material that dates back from the war days’. Paranoia, on one hand, and the need to pledge obeisance to security officials on the other, made Charbel openly call for help. And this is how I was contacted and this is how I was accompanied by security officials, to dig-out that letter. Even for security officials, it was finally an amusing story, especially that we found the letter, which gave me credibility. This is a boring village where everybody sits normally on the main street observing what’s happening. Any possible excitement is an amusement. Yet no one wanted to be on camera. Other areas in Lebanon would not have the same relationship to such a story, especially for the fact that the family was Christian in an area with no dominant Christian powerful leader.

Chad Elias:

You recorded sounds during the war. This is something that you also did from a very early age. Could you talk about this interest in sound? In In This House it manifests itself as a fascination with language. Could you say something about the layering of sounds and images in the video? I am particularly interested in your use of off-screen sound and non-synchronous editing.

Akram Zaatari:

The ambient sounds you hear in the video are part of the digging rushes. I did not play with that. The only sound addition is the beep sound at the end when the silhouettes appear. Since I was a child – part of my generation I guess – I was interested in radio. Recording was a way to make your own radio program at home. When I started to take pictures, I also started to record audio, but unfortunately I often re-recorded on top, erasing them since I did not have many empty cassettes to play with. So each year I would erase the sounds that did not interest me anymore. I stopped doing that in the mid-1980s when I left for Beirut. In Beirut I recorded stuff that I sent to my parents, like an audio letter similar in nature to what the artist Rabih Mroué’s family did (Face A/Face B 2001). Shortly after the assassination of Hariri I decided to record audio only. It all started because my camera was not working, and then I liked it. An audio tape recorder is much less present than a camera. The use of sound in This Day is by far more complex, where I looked for how to best show sound documents. Sometimes I came up with scenes only because they go better with a sound document. Normally in film you do the opposite.

Chad Elias:

In This House is also about the relation between archaeology and the construction of historical knowledge. By showing the digging, you seem to want to highlight the act of excavation as much as the objects that are unearthed by it.

Akram Zaatari:

I used digging first as a recording of a process, without any pretentions. Had we not found the letter, I do not know what I would have done with the rushes. With time, the image of digging became emblematic of my work, my interest in excavation, unearthing documents. I am a curious person, and my curiosity reaches out to others’ social spaces and other time spaces. In this sense, what I am doing has more to do with the present than with the past. I did not want to reduce the letter concealed in the mortar shell to the status of a found historical artifact. It is a naïve letter after all.

Chad Elias:

Your video Nature Morte (2008) records the actions of two men silently preparing for a military action. In the video, we see an older man patiently constructing a homemade bomb while a younger man stitches the frayed cuff of a coat. While the older man leaves at the end, weapon on his shoulder, the younger one decides to stay. One of the notable aspects of this video is the absence of dialogue and the resulting heightened emphasis placed on gestures, actions, and objects. What ideas led you to focus on these acts of mute labour? What is the significance of the relationship between the two men and the implicitly gendered division of their tasks? Are we meant to read them as representatives of two different moments in the history of resistance movements in south Lebanon?

Akram Zaatari:

Many former resistance fighters talked about the time that preceded a military operation and described their anxiety while getting prepared for the job. I wanted to portray this silent anxiety, and at the same time portray the hesitation and the division regarding the right of arms in Lebanon today. This is, after all, what triggered the making of this video. I wanted to normalise the activity they are engaging in as well. You could read them in many ways. On the one hand, two generations, on the other, a relationship of caring and initiation. But what I was considering the most is transposing the older one in time, because this is what he did for years in the 1980s when his body was young and rugged, and today he is the one who decided to leave and disappear in the mountain, which is a bit surreal, because normally the young ones are driven to this type of activity, not the older ones. So I wanted to make the video seem outside reality.

Chad Elias:

Nature Morte takes place in the village of Hubbariyeh, only a few kilometres away from the Shebaa farms, a part of Lebanese territory that remains a source of continuing dispute with Israel.23

I was interested in the large-scale photographs that you took of this area (fig.19). The images convey the sense of a landscape under surveillance. We see houses and roads, but there are no people visible. You are documenting an area that once served as the setting for military operations carried out by the Lebanese Resistance Front. Can you talk more about how you approached this landscape in light of the history of these operations?

Fig.19

Akram Zaatari

Untitled 2007

The valley along which were built the old and new roads connecting Shebaa with Hubbariyeh

© Akram Zaatari

Akram Zaatari:

The earth is the ultimate archive. It presumably contains unlimited data, waiting to be decoded. In fields such as anthropology, geography, and geology, the landscape represents the archive that carries such data. I do not think we will ever be able to decode everything, and this is why I did portraits of landscapes, as portraits of enigmatic traces of history. One day we will possess the knowledge and the means to decode information in it. Until then, we can only preserve pictures of it. The landscapes of the Aarqub area, near the Shebaa farms, have become mythical in relation to the history of the fadaiyin, the armed Palestinian resistance in Lebanon, and later the history of the Lebanese Resistance. This is clear in the testimonies of resistance fighters who took part in the struggle under the Israeli occupation (1978–2000). Although this area is under total surveillance by Hezbollah, the UN troops, and the Lebanese army, I do not personally see it in the pictures. Before 1967 and the occupation of the Shebaa farms, the region’s economy partly depended on the farms. With the Israeli occupation, the region gradually began to depopulate, and although many families came back to live there after the Israeli withdrawal in 2000, there was no national attempt to resuscitate its dying economy. In comparison, it is really sad to see how the Israelis were able to exploit the land only a few kilometres across the border, making life for inhabitants of that region economically feasible. So for me those landscapes represent a situation that is on hold.