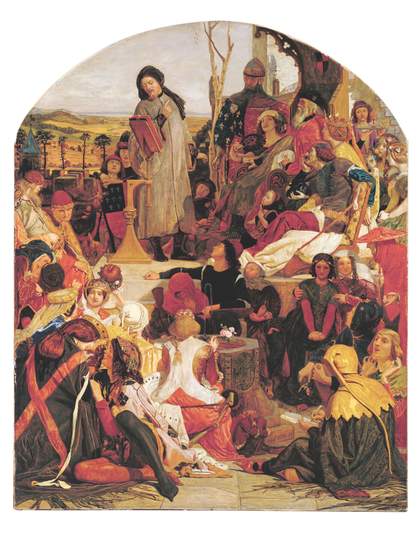

To begin with a confession: I have often paused in front of Ford Madox Brown’s Chaucer at the Court of Edward III 1856–68, but, until recently, had never properly looked at it. Having clocked the figures of Chaucer at his lectern and the listening king, I normally take a quick glance at the rest of it, admit defeat, and move on. Why? Because it is bewilderingly kaleidoscopic – as packed with people as a picture by that Victorian painter of crowds, William Powell Frith, but somehow more difficult to read. Frith is, perhaps, a telling comparison.

It was only after surveying Brown’s Chaucer that I recognised how stagey Frith’s compositions can be. Take his roughly contemporary The Derby Day 1856–8, in which the figures obligingly pose for us in little tableaux. Brown’s, on the other hand, sit around in natural poses: as they listen to the poet, they turn their backs to us or chat absorbedly to each other. I find myself wanting to walk into Chaucer and look round its corners, to tap its inhabitants on the shoulders to ask what they are thinking or why they aren’t listening. While Frith lines it all up, Brown makes us work.

Chaucer was always going to be an ambitious composition. In his diary, Brown describes searching for ‘some subject connected with the history of this Country of a general and comprehensive nature’. He was inspired by a recently published history of England that credited the brilliance of Chaucer’s works with a role in the development of the English nation. Brown was excited by the idea of connecting literature with history, and immediately ‘saw visions of Chaucer reading his poems to knights & Ladyes fair’ and to the king himself.

Complex as Chaucer is, it is only a fraction of what Brown originally intended. His first thought was to represent the author surrounded by other poets and prose writers but, on realising the scene would be too crowded, he decided to focus solely on the poets. However, even this reduced cast would not be fully realised. After beginning the work in 1845 as an elaborate triptych, Brown eventually abandoned the wings – along with Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton, Pope, Burns and Byron. Instead, he concentrated on the central panel, leaving Chaucer to carry the symbolic weight of English literature alone. And consider this: the picture in Tate Britain is actually a replica that Brown and his assistants made of his original, larger version of the painting, which is now in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Australia. At over three and a half metres high and nearly three metres wide, this picture offers an immersive experience, filling one’s field of vision. It is so huge that it seems to absorb the viewers themselves into its listening crowd.

‘I find myself wanting to walk into Chaucer and look round its

corners, to tap its inhabitants on the shoulders’

But perhaps Brown’s vision of Chaucer had to be complex. For one thing, The Canterbury Tales itself, which includes the ‘Legend of Custance’ told by the Man of Law, offers a busy panorama of human nature. There is another factor too: to give his picture the necessary authority, Brown seems to have reworked elements from a manuscript illumination from the early 15th century – a frontispiece to Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde showing the author reading to a richly dressed group on a wooded hillside. It is a crowded image, its composition similarly difficult to untangle.

Despite the authenticity of this source, and the care with which he studied medieval costumes, Brown wanted to represent England’s past in a way that made it look fresh, real and new. I have suggested that his Chaucer is strikingly naturalistic, and this was Brown’s intention. It is apparent in the unconventional, often casual, poses of his models (who included his wife Emma, daughter Lucy and, representing Chaucer himself, his friend Dante Gabriel Rossetti). It can also be seen in the quality of light.

‘This picture is the first in which I endeavoured to carry out the notion … of treating the light and shade absolutely,’ Brown wrote, ‘as it exists at any one moment, instead of approximately, or in generalised style. Sunlight not too bright, such as it is pleasant to sit in out of doors, is here depicted.’ Just after he read the history of England that suggested his subject, he travelled to Rome, where, over seven months, he was exposed not only to Renaissance paintings but also a southern climate. It was his fresh reimagining of English history ‘amid air & sun shine’, as he put it in his diary, that eventually stopped me in my tracks and made me want to join Chaucer’s audience.

I have often banged the drum about spending more time in front of pictures in museums. Read the label if you wish, but what is so much more important is looking at the paintings. Really looking. Letting your eye creep like an insect over their surfaces. When I finally took my own advice with Ford Madox Brown’s Chaucer, I found a treasure.

Chaucer at the Court of Edward III was purchased in 1906 and is on display at Tate Britain.

Susan Owens is former Curator of Paintings at the V&A and is an independent scholar. Her latest book Imagining England’s Past is published by Thames & Hudson.