Modernism and the Sublime

Philip Shaw

In the modern era, the sublime took on new meaning, going into the territory of the infinite and the unknowable, working in what Cézanne called ‘iridescent chaos’. Philip Shaw reflects on modernism and the sublime, contrasting dada, surrealism and art informel with De Stijl, suprematism and abstract expressionism, and looks to the ideas that inform the search for the sublime today.

Mockery and blockage

In his ‘Ten O’Clock’ lecture, delivered in London in February 1885, the painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler mounted a sneering attack on the commercial and state appropriation of the arts. Singling out for particular opprobrium John Ruskin’s doctrine of ‘truth to nature’, the artist claimed that while the common man wishes ‘to see, for the sake of seeing’, the painter, by contrast, ‘does not confine himself to purposeless copying’ but rather seeks the realisation of an ideal.1 Rejecting the public’s ‘delight in detail’, the painter discarded also the stale, hackneyed discourse of the sublime: ‘how dutifully the casual in Nature is accepted as sublime, may be gathered from the unlimited admiration daily produced by a very foolish sunset’.2 The spread of a vulgarised vocabulary of sublimity had, in Whistler’s view, led to a decline in artistic judgement. For critics trained in this vocabulary, a mountain is ‘synonymous with height – a lake, with depth – the ocean, with vastness – the sun, with glory. So that a picture with a mountain, a lake, and an ocean – however poor in paint – is inevitably “lofty,” “vast,” “infinite,”and “glorious” – on paper’.3

James Abbott McNeill Whistler 1834–1903

Nocturne: Blue and Silver - Cremorne Lights 1872

Oil on canvas

support: 502 x 743 mm; frame: 810 x 1062 x 105 mm

Tate N03420

Bequeathed by Arthur Studd 1919

Fig.1

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Nocturne: Blue and Silver - Cremorne Lights 1872

Tate N03420

A further point of disturbance is provided by the indeterminate form floating in the centre of the painting. Most likely a barge, the vague, amorphous shape nevertheless seems eerily human and, as such, is suggestive of the river’s association with violence and death.4 It takes time to conceive that the shape drifting towards us may be a dead body, but once this possibility is grasped we become subject once more to the uncanny force of the painting’s gaze. ‘Photo-graphed’, as the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan describes it, from the perspective of the no longer human, our self-fashioning as vital and heroic, perhaps even sublime, undergoes a debilitating transformation.5 Instead of penetrating a mystical horizon, the viewer is confronted with an intimation of mortality that is alternately repellent and fascinating. To adapt the scholar David Ellison’s distinction, the force, or energeia, of the painting is such that the viewer can no longer, as in traditional conceptions of the sublime, establish themselves in relation to a coherent boundary; instead of possessing the sublime, the ‘would-be possessor’ finds him or herself unwittingly possessed by the uncanny.6

Paradoxically for a work so apparently invested in the artificial and idealised, Cremorne Lights is radically materialist in its approach to the sublime. With its unsettling reminders of the intense pleasure of self-dissolution, Whistler’s painting challenges the traditional notion of the sublime as a staging ground for the triumphant recovery of the self from the jaws of destruction. Just as the anamorphic form in the foreground prevents the ego from encompassing the work in its totality, so those other contrivances – the decorative foliage and butterfly icon – draw attention away from the illusion of depth towards the reality of the painted surface, suggesting, in opposition to conventional Victorian narrative painting, that there is nothing beyond this painted surface.7

What the painting achieves, therefore, is a sustained interrogation of its very status as a painting; neither wholly committed to flatness nor to depth, Cremorne Lights exceeds the discourse of the sublime precisely as a result of its critical engagement with all that that discourse entails: the elevation of the spiritual over the material; the disclosure of truth behind the veil of appearances; the triumph of the rational over the sensual. Still further, through its investment in the artificial rather than the ‘reality of the moment’, which modernism proudly proclaims as its mark of authenticity, Cremorne Lights announces itself as both timely and belated, as if the painting were observing itself failing to be new.

In 1886, a year after Whistler had shocked his London audience, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, in the preface to The Gay Science, advanced a related attack on the worn-out taste for the sublime:

How the theatrical scream of passion now hurts our ears, how strange to our taste the whole romantic uproar and tumult of the senses has become, which the educated mob loves, and all its aspirations after the sublime, lofty and weird! No, if we convalescents still need art, it is another kind of art – a mocking, light, fleeting, divinely untroubled, divinely artificial art that, like a pure flame, licks into unclouded skies.8

In many respects Whistler’s sly undermining of the stereotypical sublime meets Nietzsche’s criteria for ‘another kind of art’. And yet, for all its mockery of the taste for the vast, the grand and the infinite an air of melancholy taints Cremorne Lights, transforming pleasure into sickness, reducing mockery to sad laughter. In holding up a mirror to the ‘educated mob’, the Whistlerian sublime succeeds only in disclosing the conditions in which bourgeois identity is forged while stopping short of an out-and-out transfiguration of those conditions.

John Martin 1789–1854

The Plains of Heaven 1851–3

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1988 x 3067 mm; frame: 2415 x 3485 x 175 mm

Tate T01928

Bequeathed by Charlotte Frank in memory of her husband Robert Frank 1974

Fig.2

John Martin

The Plains of Heaven 1851–3

Tate T01928

Gustave Courbet 1819–1877

The Source of the Loue 1864

Oil on canvas

984 x 1304 mm

Photo © National Gallery of Art, Washington

Fig.3

Gustave Courbet

The Source of the Loue 1864

Photo © National Gallery of Art, Washington

It is Courbet’s acknowledgement of this hard kernel at the heart of the sublime that accounts for the unstintingly tragic tone of his progressive realism. This tragic note, concomitant with the self-subverting qualities of the painting’s claims to modernity, is echoed, notoriously, in The Origin of the World (L’Origine du Monde) (Musée d'Orsay, Paris)14. Commissioned in 1866 by Khalil Bey, a connoisseur of erotic art, the painting depicts the naked torso of a woman enclosed within coarse swirls of linen. Conceived as a concentric sequence of naturalistic frames, the centrepiece of the image is a carefully rendered vagina, the slightly parted vulva surrounded by dark and abundant pubic hair. The hidden realm of sexuality, symbolised by the yawning darkness of the grotto in the earlier painting, is here rendered explicit. One could even go so far as to say that the latter painting functions as a ‘desublimation’ of the former. As the philosopher Slavoj Zizek comments in The Fragile Absolute (2000), Courbet’s painting directly depicts ‘what previous realistic art merely hinted at as its withdrawn point of reference’. By bringing ‘the sublime object’ down to earth, as it were, by showing that the real object of desire is not a transcendent, unknowable ‘Idea’ (in the Kantian sense) but a fleshy, material thing, The Origin of the World goes even further than The Source of the Loue in assaulting the foundations of modern masculine self-fashioning.15 Like the Whistlerian corpse, Courbet’s impenetrable darkness turns out to be an abject object. As the philosopher Julia Kristeva has argued, the abject is related to the uncanny by virtue of its capacity to exceed the distinctions between subject and object, self and other. Neither one thing nor the other, as vomit, faeces or corpse, the abject is a reminder of the primal repression preceding the subject’s entry into the symbolic order. As such, the abject marks the point at which the subject differentiates itself from the mother and thereby learns to discern the boundaries between ‘I’ and the other.16

With Kristeva’s theorising in mind, we might wish at this juncture to reflect on why female sexuality should have become the ‘dead-end’ of the Romantic sublime. In a recent critical response to Hertz’s reading of the sublime, the scholar Christine Battersby observes how the male ego constitutes itself through the encounter with a specifically feminine form of excess. Within this encounter woman is figured as:

the unknowable unconscious of man (his ‘Other’): an elusive absence that underlies the I, and which marks the limits of the knowable and the representable, while simultaneously acting as a continual allurement to the consciousness which it haunts. As such, ‘woman’ represents both the ‘beautiful’ object of desire and the ego’s drive towards its own dissolution which is warded off via the structures of the sublime.17

As an outline of Hertz’s account of the sublime this seems true enough; in Hertz’s readings of Pseudo-Longinus, Kant, Wordsworth and George Eliot, a unified self is established when the ego cuts itself from the indeterminate, chaotic feminine principle to which it is initially bonded.

Where I depart from Hertz – and indeed from Battersby’s critique of Hertz – is in the assumption that art is unable to reflect on or intervene in the process by which feminine sexuality is converted from the structural limit of masculine self-fashioning into its ineffable metaphysical Other. A reading of Courbet’s The Source of the Loue that regards the terror of the cave as a representation of the masculine ego’s fear of being absorbed by a mysterious feminine beyond thus misses the point: the true source of terror is the realisation of the non-existence of this beyond. What the painting discloses, I would suggest, is the means by which a conception of feminine excess or abjection functions as the illusory Other of masculine integrity, an Other created by patriarchy as a means of filling in a fundamental emptiness. In The Origin of the World the structure of this illusion is made explicit. As Zizek argues, the recalcitrant fleshiness of the painting indicates how femininity actually functions in the sublime economy of masculine self-fashioning: not as the absent, ineffable beyond of the phallus but as an indicator of the material limits of the phallus beyond which there is nothing.18

Nature and ekstasis

At the time of writing The Gay Science, Nietzsche was seeking an alternative to the baleful restrictions of the Romantic sublime. In the previous decade he had expressed the contest between excess and limitation in terms of that between the Dionysian and Apollonian principles. Just as Kant had asserted the primacy of the mind over the chaos of sensual existence by portraying reason triumphing over the threat of destruction from the excessive and the unquantifiable, in The Birth of Tragedy (1872) Nietzsche depicts the Apollonian as the veiling, healing, transfiguration of Dionysian horror, converting terror into action and making ekstasis, or being outside of oneself, intelligible. Thus tempered, the mind paradoxically forgets the specificity of its initial encounter with the raw materiality of the world; the cost of individual and collective ‘health’ is a willed negation of otherness.

At the time of writing The Gay Science, Nietzsche was seeking an alternative to the baleful restrictions of the Romantic sublime. In the previous decade he had expressed the contest between excess and limitation in terms of that between the Dionysian and Apollonian principles. Just as Kant had asserted the primacy of the mind over the chaos of sensual existence by portraying reason triumphing over the threat of destruction from the excessive and the unquantifiable, in The Birth of Tragedy (1872) Nietzsche depicts the Apollonian as the veiling, healing, transfiguration of Dionysian horror, converting terror into action and making ekstasis, or being outside of oneself, intelligible. Thus tempered, the mind paradoxically forgets the specificity of its initial encounter with the raw materiality of the world; the cost of individual and collective ‘health’ is a willed negation of otherness.

Although in the aftermath of The Birth of Tragedy Nietzsche began to explore alternatives to the Apollonian mode, for the most part he manages only to hint at what might lie beyond the limits of the German Idealist sublime. The task of jettisoning the Kantian philosophy that enables the bourgeois subject to regard itself as ‘lofty’ and incomprehensible and that, by extension, allows it to represent the Other merely as a reflection of that which it must exclude in order to posit itself as individuated, masterful and free, remains largely unrealised.19

Nevertheless, as Battersby has proposed, there are suggestions throughout Nietzsche’s work of an alternative to the Kantian mode of sublimity. While the Apollonian orientates the subject along the path of bourgeois individuation, the Dionysian Other threatens always to break through, diverting consciousness towards an acknowledgement of its inherent emptiness and an affirmation of the terrifying pleasures of self-overcoming. An awareness of the potential for material difference to exceed the imposition of instrumental reason is evident even in the work that Nietzsche produced around the same time as The Birth of Tragedy, as the following extract from the essay ‘On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense’ (1873) illustrates:

Every concept arises through the equation of unequal things. Just as it is certain that one leaf is never totally the same as another, so it is certain that the concept ‘leaf’ is formed by arbitrarily discarding these individual differences and forgetting the disturbing aspects. This awakens the idea that, in addition to the leaves, there exists in nature the ‘leaf’: the original model according to which all the leaves were perhaps woven, sketched, measured, colored, curled, and painted – but by incompetent hands, so that no specimen has turned out to be a correct, trustworthy and faithful likeness of the original model ... We obtain the concept, as we do the form, by overlooking what is individual and actual; whereas nature is acquainted with no forms and no concepts, and likewise with no species, but only with an X which remains inaccessible and undefinable for us.20

Nature, that is, persists in its irreducible otherness despite our best efforts to present it as an object of consciousness. When, as Battersby argues, the artist ‘forgets’ material differences in the act of representing a concept (of a leaf, for example), ‘material differences are not simply negated but remain on the fringes of consciousness’ thereby raising ‘the possibility of an encounter or an intuition’ that ‘smashes’ conceptual understanding to pieces.21

The artist whose work seems most closely related to Nietzsche’s conception of the sublime is Paul Cézanne. As is well known, Cézanne’s art has traditionally been understood as an attempt to reconstruct the primacy of the tangible world, prior to the imposition of representational frameworks. According to this understanding, the artist strives to convey a sense of the world in its raw immediacy, enabling differences to emerge from simple observation.22 In essence, what Cézanne’s art accomplishes is a realisation of the otherness of nature and a vision of the sublime freed from the fiction of self-realisation. One could go further and claim that such art goes beyond the mordant deconstruction of phallic mastery observed in Courbet and Whistler. As we shall see, however, Cézanne’s expression of the experiential or Dionysian sublime is not without its contradictions.

Paul Cézanne 1839–1906

The Grounds of the Château Noir circa 1900–6

Oil on canvas

support: 907 x 714 mm

Lent by the National Gallery 1997

On long-term loan to Tate L01891

On long-term loan to Tate L01891

Fig.4

Paul Cézanne

The Grounds of the Château Noir circa 1900–6

Lent by the National Gallery 1997

On long-term loan to Tate L01891

On long-term loan to Tate L01891

A yearning to apprehend rather than merely infer the unrealisable beyond of representation is therefore central to Cézanne’s vision; as the artist remarked to his friend Henri Gasquet: ‘under this fine rain I breathe the virginity of the world. I feel myself coloured by all the nuances of infinity. At this moment I am one with my canvas. We are an iridescent chaos.’24 In The Grounds of the Château Noir the attempt to capture the ‘virginity of the world’ – prior, perhaps, to its transformation as the origin of the world – leads to a blurring of the lines between painter and painting, self and Other. The viewer, too, is undoubtedly seduced by this process. An ‘irritable reaching for fact and reason’, that prime characteristic of critical judgement, is absorbed in rapturous contemplation.25

And yet, before too long, the endeavour to become one with the ‘moment’, to lose oneself in lustrous indifference, is baffled by the return of the very distinctions – cognitive, temporal and representational – that the artwork seeks to efface. One could argue that the return of these distinctions renders Cézanne’s painting Kantian after all since what is affirmed here is not the recovery of a pre-individual, Dionysian relation with the plasticity of the world but rather the return of Apollonian measure and division: in short, the painting can be interpreted as a rather tragic meditation on the triumph of instrumental Reason.

Not long before his death, the artist wrote: ‘I am becoming more lucid before nature, but with me the realising of sensations is always painful. I cannot attain the intensity that is unfolded before my senses.’26 In Kant’s ‘Analytic of the Sublime’ (1790), the realising of sensations becomes painful when the faculty of Imagination, responsible for the representation of sensual phenomena, discovers its inability to comprehend an overwhelming magnitude or multiplicity. In the Kantian schema, the failure of Imagination to present an Idea of the sublime serves to ‘negatively’ exhibit the higher faculty of Reason. Thus, the subject is made aware of a capacity for self-realisation ‘essentially transcendent to (that is, free from) all determinations of nature, inner and outer’.27 With Cézanne, however, the focus on the traumatic failure of sensible intuition goes well beyond the recuperative dialectic of Kant’s sublime. Instead of conveying a negative awareness of Reason, the failure of the painter’s endeavour leads, inexorably, towards the moment when the sensual qualities of paint, what we might call its materiality, become strikingly apparent.28 For Cézanne, that is, a painful awareness of the inadequacy of form and content, an inadequacy directly related to the impossibility of presenting a synthesis between the mind and the world, culminates not in the discovery of a capacity for transcendence but in the acknowledgement of the mind’s entanglement with the alien matter of the world. Painting, for Cézanne, therefore becomes an endeavour to unveil a mode of otherness that is not simply a reflection of the knowing subject but is related to the pre-individual, inchoate drives of the body.

In a similar vein, the philosopher Jean-François Lyotard has argued that what Cézanne’s painting thus reveals is the unconscious or ‘figural’ aspect of visualisation, the Dionysian materiality that must be suppressed, rendered invisible, so that visual coherence may emerge.29 With each interminably suspended brush stroke, ‘the disturbing aspects’ of the individual leaf threaten constantly to erupt in the midst of representation.30 The appeal of Lyotard’s Nietzschean interpretation of Cézanne is easy to grasp. Where Kantianism blocks access to the living or sensual world, locating truth in a veiled, abstracted realm beyond the reach of understanding, Nietzsche seems to offer in its place the possibility of a blissful, unmediated contact with nature and the body. However, what Nietzsche neglects in his privileging of the openness of the corporeal to alien otherness is the sense in which the life-energy of the world is informed, and indeed pre-dated, by an unnatural, mechanical force.

In his later works Nietzsche himself makes reference to the blind autonomy of the will to repetition, otherwise known as the principle of the eternal return. Only a being willing to say ‘yes’ to the return of life, in the full acknowledgement of life’s pain as well as its glory, can unshackle itself from the fiction of truth hidden behind the veil of illusion. For Battersby, what is sublime in the work of the later Nietzsche ‘is the will to repetition’ in which ‘there is no “beyond” and also no concealment’. The ‘I’ that emerges from this process is not derived from an encounter with an ‘“other” to which it is opposed’ but is located in a dynamic relation with alien multiplicity and difference.31

There is, however, within the will to repetition a notion of absolute difference that casts all attempts at affirmation into doubt. In order to grasp this notion we may usefully consider the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud’s discussion of repetition in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920). As is well known, in this text Freud argues that the desire for joy or pleasure is inseparable from the appetite for destruction. Indeed, as he goes on to suggest, it is the death drive that exists prior to the life instincts, which aim for reunion with the primary state of inertia. When, to extend this reading, in the experience of the sublime the subject encounters an object that prompts a painful or excessively pleasurable response, it is at this moment that the subject is made suddenly aware of the organic insufficiency of being, and that life is possible only as a result of the intervention of the death instinct. In his revision of Freud, Jacques Lacan insists that the death instinct has nothing to do with the organic body. Rather, ‘the death instinct is only the mask of the symbolic order’.32 Just as the subject only comes into being as a result of submitting its primary desires to the mechanical defiles of the Symbolic, so the Nietzschean conception of Dionysian vitality cannot be separated from the mortifying effects of the eternal return.

Similarly, for Cézanne it is not the joyful intensity of nature that is revealed in The Grounds of the Château Noir but the realisation of a painful drive persisting beyond and intervening in the life of the world. For Lacan, as I have suggested, this drive is synonymous with the symbolic order. The disclosure of this drive is ‘painful’ because it comes perilously close to revealing the moment in which artistic ‘illusion as such in some way ... destroys itself ... by demonstrating that it is only there as a signifier’.33 The point again is not that Cézanne’s brushstrokes recall a hidden realm of vitality, which conventional representation fails to perceive (for the phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty: the object in the course of its appearing; for Lyotard: the invisible), but rather that the otherness of nature itself only comes into being as a result of the intervention of that shocking drive or ‘X’, the uncanny dimensions of which, as Nietzsche himself insists, remain ‘inaccessible and undefinable for us’. With Cézanne, therefore, poised between the virginity of the world and the deathly realm of the Symbolic, we arrive at the point at which a new and disturbing conception of the sublime begins to emerge. What these brush marks signify is not the resurgence of an occluded world, but the anamorphic oozings, the traces of the Real that remain when the world submits to signification.

Towards the abject

In 1900, in The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud presented a case study in the relations between the world, the flesh and the Symbolic. As with many of the examples discussed in this essay, Freud framed his analysis in terms of a sublime encounter with female sexuality. A few years earlier he had treated a friend of the family, a young woman known as Irma, suffering from hysteria. He notes that this treatment had only limited success and that the patient was not relieved of her symptoms. Shortly after the termination of the analysis Freud was visited by his friend Otto, who had been staying with Irma and her family in the country. Otto reported, somewhat reproachfully in Freud’s view, that Irma, although a little better, was not entirely well. In the evening Freud decided to write out the woman’s case history, with the idea of giving it to ‘Dr M. (a common friend who was at that time the leading figure in our circle’. The analyst then had a dream:

A large hall – numerous guests, whom we receive. – Among them Irma, whom I immediately take aside, as if to answer her letter, and to reproach her that she doesn’t accept the ‘solution’ yet. I say to her: ‘If you still get pains, it is really only your fault.’ – She answers: ‘If you knew what pains I have now in my throat, stomach and abdomen, it’s tightening me up.’ – I am startled and look at her. She looks pallid and puffy; I think, after all I am overlooking something organic. I take her to the window and look into her throat. With that she shows some resistance, like women who wear a denture. I think to myself, she doesn’t need to do that. – Her mouth then opens properly, and I find on the right a large white spot, and elsewhere I see some remarkable curled structures which are evidently patterned on the nasal turbinal bones, extensive white-grey scabs. – I quickly call Dr M., who repeats and confirms the examination ... Dr M. looks entirely different from usual; he is very pallid, limps, is beardless on the chin ... My friend Otto now also stands next to her, and my friend Leopold percusses her over the bodice and says: ‘She has a dullness below on the left,’ points also to an infiltrated portion of the skin on the left shoulder (which I, in spite of the dress, just as he, feel) ... M. says: ‘Without a doubt, it’s an infection, but it doesn’t matter; dysentery will follow and the poison will be eliminated ...’ We also directly know where the infection comes from. Recently my friend Otto, when she was not feeling well, gave her an injection of a preparation of propyl, propyls ... propionic acid ... trimethylamin (whose formula I see in heavy type before me) ... one doesn’t give such injections so lightly ... Probably, too, the syringe wasn’t clean.34

In the dream Freud reproaches his patient for failing to accept his ‘solution’ (in German, the word is ‘lösung’, meaning both the solution one injects and the solution of a conflict). The talking cure thus results in a deadlock: Irma cannot symbolise, literally give voice to, the reality of her desire and Freud is unable to persuade her of the efficacy of his solution. It is at this moment that the dream shifts from the verbal to the visual realm: Freud is ‘startled’ and looks at Irma who, after some initial resistance, concedes to open her mouth. No words, no magic solution, issues from this orifice; instead, what the analyst perceives is terrifying: the turbinate bones covered with dull grey scabs conjures a host of associations from the nose, to the mouth to the female sexual organs (at around this time Freud had endured an operation on his turbinate bones). As Lacan remarks, there is

a horrendous discovery here, that of the flesh one never sees, the foundation of things, the other side of the head, of the face, the secretory glands par excellence, the flesh from which everything exudes, at the very heart of the mystery, the flesh in as much as it is suffering, is formless, in as much as its form in itself is something which provokes anxiety. Spectre of anxiety, the final revelation of you are this – You are this, which is so far from you, this which is the ultimate formlessness.

For Lacan, the disclosure of this ‘unnameable ... unlocatable form ... the abyss of the feminine organ from which all life emerges, this gulf of the mouth, in which everything is swallowed up’ is ‘a revelation of that which is least penetrable in the real, of the real lacking any possible mediation, of the ultimate real, of the essential object which isn’t an object any longer’. At this point, Lacan concludes, ‘there’s no Freud any longer, there is no longer anyone who can say I’.35

How does Freud recover from this encounter with formlessness? As with Kant’s narrative of the sublime, the disclosure of the abyss is a structural dislocation, granting a negative exhibition of a higher, synthesising faculty. By way of an appeal to the paternal authority of Dr M., the Freudian ego is rescued from dissolution; Irma’s malady, after all, turns out to have a somatic origin, and the fault lies, not with Freud, but with his friend Otto.

But the chain of release from guilt and anxiety does not end there. Miraculously, as Lacan notes, Freud’s nightmare changes into ‘a sort of ataraxia’, a state of blissful lucidity brought about by the production of the formula of trimethylamin, a chemical substance associated with the decomposition of vaginal secretions and male ejaculate.36 The dreamer’s salvation is thus precipitated by a retreat from visual terror and a return to verbal order. Lacan notes that the formula, which Freud sees written in ‘heavy type’, enables him to convert the traumatic abyss of the Real into the sense-making realm of the Symbolic.37 By nominating this solution, Freud recovers the integrity of the theory on which he founds his identity: ‘Thus this substance led me to sexuality, the factor to which I attributed the greatest importance in the origin of the nervous disorders which it was my aim to cure.’38

The ego’s deliverance comes at a price, however. The release from the Real is accomplished only by submitting the integrity of the ‘I’ to a series of partial identifications: the imaginary father, Dr M.; the dutiful friend, Leopold; the ‘beloved enemy’, Otto.39 Dispersed among these functions, the Freudian ego replaces the knowledge of its primary guilt with the reassurance of professional validation. As Lacan comments, the intervention of ‘the symbolic function in its most radical, absolute usage [thus] ends up abolishing the action of the individual so completely that by the same token it eliminates the tragic relation to the world’.40

According to Lacan, in the visual arts in the first half of the twentieth century, responses to the encounter between the suffering intensity of the flesh and the regulatory mechanisms of bourgeois identification seem roughly divided. On the one hand, we may identify an art that seeks to dispel the illusory transcendence of the Real through an insistence on radical desublimation, thereby forcing an encounter with various forms of occluded matter; on the other, an art that seeks to re-establish the minimal gap separating the void at the heart of the Real from the object that informs it, thereby reanimating an idea of the beyond. To the former group we might assign movements such as dada, surrealism and art informel; to the latter De Stijl, suprematism and abstract expressionism. The distinction between these groups turns on their respective treatments of the Real in its relation with the Symbolic. But in order to understand the specificity of these treatments we must first consider Lacan’s subsequent examination of the sublime in his seminar of 1959–60, later published as The Ethics of Psychoanalysis.

To be exact: for Lacan what modernist art attempts to convey is not the Real itself but the enigmatic void or absence that resides at the core of the Real, otherwise known as the Thing (das Ding). For Lacan, it is the emptiness of the Thing that marks the point at which the Real lends itself to signification. The Thing can thus be conceived as ‘that which in the real suffers from the signifier’; as void or absence it assists in the creation of meaning yet prevents meaning from ever being complete. The Thing is therefore ‘characterised by the fact that it is impossible for us to imagine it’.41 Objects, Lacan goes on to explain, become sublime when they are raised to ‘the dignity of the Thing’. By way of a reversal of the Freudian concept of sublimation, objects that come to inhabit the gap at the heart of the Real maintain their material specificity (for example, as clothing, flesh or dirt) even as they resonate with elevated glitter or Schein. When considering the sublime in this light it is thus important to remember that the sublime object is nothing in itself, but is rather a mere secondary positivisation of the void or Thing that inhabits the Real.

What happens when art attempts to inform this Thing? In the art of desublimation (a category that extends from Courbet’s The Origin of the World and that includes works as varied as Meret Oppenheim’s Breakfast in Fur (Dejeuner en Fourrure) 1936, and Robert Rauschenberg’s Dirt Painting [for John Cage] 1953)42 we find ‘that if we force our way through ... to the Thing itself, all we will get is a suffocating nausea of the abject’. In other words, all we encounter is the object in its recalcitrant material specificity. In the art of sublimation, by contrast, we discover ‘the matrix of sublimation at its most elementary’, that is, as purely structural opposition between the Real and the Symbolic. 43

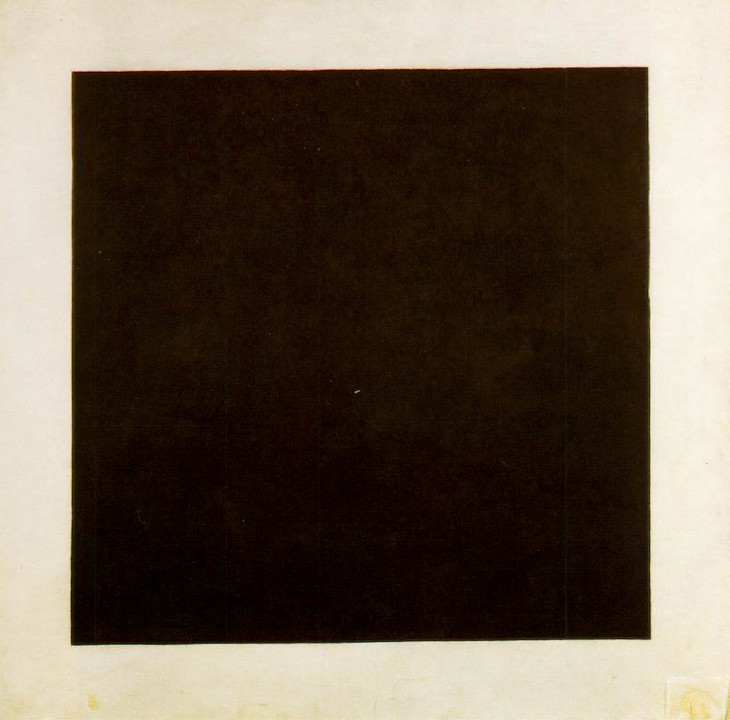

In The Fragile Absolute, Zizek explains this distinction in terms of the opposition between Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square on a White Background 1915 (fig.5) and Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain 1917. From the outset, Malevich sought to affirm the value of abstraction over realism, announcing in his suprematist manifesto that ‘the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling’.44 True to these principles, Black Square on a White Ground is radically non-representational. The slab of black paint that dominates the canvas works as grand refusal, repudiating nature in favour of pure abstraction. As such, the painting can be conceived, in Kantian terms, as a negative representation of the supersensible. Still further, it can be seen as an attempt to transcend the material restrictions of representation, presenting a feeling or impression of the divine. Malevich himself regarded his minimalistic geometrical forms as the secular equivalents of Russian icons, a form of painting which aspires to present the divine as pure or unmediated reality. This idea is corroborated by a comment from the diary of the artist’s friend, Varvara Stepanova, dating from 1919: ‘If we look at the square without mystical faith, as if it were a real earthy fact, then what is it?’45

Yet there is, as Zizek has suggested, another way to understand the sacred quality of Black Square. Through its stark distinction between the empty, elementary space of creation (the white background/surface) and the material object (the dark, material stain of the black square), Black Square on a White Ground isolates the minimal gesture that is required to raise an Idea of the divine. In the ‘Analytic of the Sublime’ Kant makes the point that the feeling of enthusiasm for the divine is linked directly to the failure of representation: ‘Perhaps the most sublime passage in the Jewish Law is the commandment: Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven or on earth, or under the earth, etc.’46 However, as Zizek confirms, the problem with Kant’s determination of the thing-in-itself is that it assumes the existence of this thing as some sort of positive determination persisting beyond the field of representation. By way of Hegel, Zizek goes on to claim that Kant’s conception of the breakdown of representation should be understood ‘literally’. In other words, rather than perceiving this breakdown as a negative indication of a supersensible realm beyond phenomenality we should regard it as confirmation that there is, once again, ‘nothing beyond phenomenality’.47

Marcel Duchamp 1887–1968

Fountain 1917, replica 1964

Porcelain

unconfirmed: 360 x 480 x 610 mm

Tate T07573

Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1999

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2002

Fig.6

Marcel Duchamp

Fountain 1917, replica 1964

Tate T07573

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2002

Reduced to the ‘bare marking of the distance between foreground and background, between a wholly “abstract” object (square) and the Place that contains it’, Black Square and the abstraction it inspires (from Barnett Newman to Ad Reinhardt) may therefore be conceived as a quasi-transcendental ‘reaction’ to the insistent matter of the world.50 More particularly, it identifies the means by which visual art seeks to sustain itself in relation to the terrifying excess of the uncanny sublime. Freud, as we noted earlier, gives an indication of what is lost when excess submits to symbolic gentrification: when the abyss is filled in with symbolic chatter the man of reason is returned to his rightful place. And with this return comes the loss of tragic authenticity. As Eagleton argues, the combative staging of the sublime is a diffuse, aestheticised version of the ‘uproarious violence’ of the old, feudal regime. And so ‘tragedy [is] repeated as comedy’.51 Like the murder scene depicted in René Magritte’s The Menaced Assassin (L’Assassin Menacé) 1926 (MOMA, New York), the bourgeois subject turns his back on the horrific truth of the sublime (the dead body on the couch), preferring to gaze at the symbolic equivalent of the ‘impossible’ Real (the gramophone horn as a representative of the sexualised Thing) rather than encounter it directly.52 The death drive that led him to engage in violence in the first place is thus substituted for the pleasurable circulation around a domesticated abyss; and with this substitution comes the dispersal of the ego and the externalisation of guilt and agency: the voyeuristic observers at the window; the hidden policemen about to spring.

In Magritte’s painting the viewer apprehends the mechanism that converts the threat of the abject object into a pleasing encounter with stage-managed horror. But it is another, later work, The Looking Glass (La Lunette d’Approche) 1963 (The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas) that gets to the heart of what is at stake in the relation between abjection, sublimation and sublimity. The painting depicts a half-open window through the panes of which the viewer perceives a blue sky with some light clouds. Yet what the viewer sees in the gap between the windows is not a continuation of this scene but a stark black vertical mass. As Zizek comments, ‘the frame of the windowpane is the fantasy-frame which constitutes reality, whereas through the crack we get an insight into the “impossible” Real, the Thing-in-itself’.53 This Real is ‘impossible’ because it cannot be confronted directly, only registered as an absence when the frame is removed. That which appears to be infinite – the endless blue sky – is thus shown to be a fantasy formation dependent on the occlusion of a primary void, which symbolisation retroactively designates as the Real.

In Magritte’s painting the viewer apprehends the mechanism that converts the threat of the abject object into a pleasing encounter with stage-managed horror. But it is another, later work, The Looking Glass (La Lunette d’Approche) 1963 (The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas) that gets to the heart of what is at stake in the relation between abjection, sublimation and sublimity. The painting depicts a half-open window through the panes of which the viewer perceives a blue sky with some light clouds. Yet what the viewer sees in the gap between the windows is not a continuation of this scene but a stark black vertical mass. As Zizek comments, ‘the frame of the windowpane is the fantasy-frame which constitutes reality, whereas through the crack we get an insight into the “impossible” Real, the Thing-in-itself’.53 This Real is ‘impossible’ because it cannot be confronted directly, only registered as an absence when the frame is removed. That which appears to be infinite – the endless blue sky – is thus shown to be a fantasy formation dependent on the occlusion of a primary void, which symbolisation retroactively designates as the Real.

Marcel Duchamp 1887–1968

Fresh Widow 1920, replica 1964

Mixed media

object: 789 x 532 x 99 mm

Tate T07282

Purchased with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1997

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2002

Fig.7

Marcel Duchamp

Fresh Widow 1920, replica 1964

Tate T07282

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2002

Duchamp’s unflinching critique of the sexualised foundations of the sublime, originating in the Fountain of 1917 and continued in The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) 1915–23, reaches its apogee in Étant donnés 1944–66.54 Installed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art since the late 1960s, the work consists of an old weather-worn door in which two peep holes have been fashioned. Through these holes the viewer looks at a naturalistic diorama, consisting of a partially obscured naked woman, her legs splayed, lying on a bed of twigs and leaves. In her left hand the life-sized mannequin holds a gas lamp, while a sparkling waterfall and an idealized, picturesque backdrop complete the fairy tale setting. Surveying this work is an uncomfortable experience – and not merely because of the disturbing content. To enter the public space in which the work is housed and then to peer through the aperture is to place oneself in the difficult position of being seen to be watching. The feminist critic Amelia Jones, noting the work’s connection with Courbet’s The Origin of the World, has argued that while Courbet’s work was ‘commissioned to be viewed in the privacy of the home (like “proper” pornography), Étant donnés places pornographic content in the public arena of the museum, where the viewer can be seen (always threatening to destroy her or his voyeuristic relation with the object) ... As such, Duchamp’s piece illustrates the impossibility of voyeurism’, the fact that the consumption of the erotic is always attended by the consciousness of being assessed, judged, by the Other.55

An additional disturbance is provided by the fashioning of the mannequin’s vagina. As Jones notes, the crevice between the legs has no ‘labia majora’ or ‘labia minora’, and certainly no clitoris. Any suggestion of depth is cancelled out by the appearance of the flat, non-naturalistic depression. ‘This body’, Jones argues, ‘refuses, finally, the penetration of vision ... It turns the gaze back into the look, exposing the insufficiency of masculine attempts at visual mastery.’56 With literally nowhere to go, the relation between the mannequin and the viewing subject is reversed: the subject becomes the object of the diorama’s gaze. Unable to convert the depthless, hairless, resolutely ‘impossible’ vagina into a signifier of feminine lack, the penetrating masculine gaze is transformed into a mere look. All that is given, as it were, in the view from this room is a vision of ‘the fact that [the] subject is not self-sufficient but constitutes his or her coherence in relation to that which he or she works to master’.57

Beyond abstraction

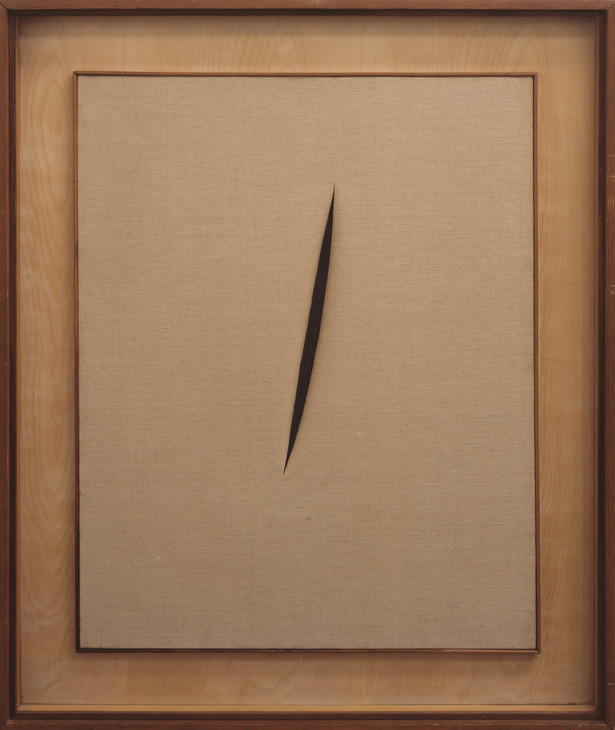

Lucio Fontana 1899–1968

Spatial Concept 'Waiting' 1960

Canvas

unconfirmed: 930 x 730 mm; frame: 1161 x 982 x 86 mm

Tate T00694

Purchased 1964

© Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milan

Fig.8

Lucio Fontana

Spatial Concept 'Waiting' 1960

Tate T00694

© Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milan

What happens when we subject abstract expressionism to this kind of critique? In 1948 Newman, in ‘The Sublime is Now’, famously declared that ‘the impulse of modern art’ resides in the ‘desire to destroy beauty’. The problem with beauty, according to Newman, is that it prevents the artist from realising ‘man’s desire for the exalted’, in other words for the sublime. In religious art, in particular, a preoccupation with the beautiful, with its emphasis on the figurative, the perfection of form and the ‘reality of sensation’, has impeded the perception of ‘the Absolute’.59 Despite his reservations about Kant, Newman believes that the sublime is on the side of mind rather than nature; and since the extent of the mind is unbounded it cannot be adequately represented by an object with determinate bounds. Inspired by the art critic Clement Greenberg’s pronouncements on the ‘flatness’ of modern painting, Newman averred that painting should seek to ‘destroy’ or ‘neutralize’ the material support of the image. A painting, that is, should strive to abolish the false infinity attendant on traditional, perspectival space. What Newman calls the ‘terror of [the] blank area’ is thus related to the opening up of the abyssal potential of the flat ground. As the art historian Pierre Schneider comments, to ‘represent the infinite, as perspective claims to do, is to comprehend it in both meanings of the word: “to understand” but also to “contain,” and to contain is to limit’. In order to paint ‘the impossible’, the artist must therefore endeavour to unlimit the relation between ground and figure: the infinite is not revealed by the ‘illusion’ of the receding horizon but rather by the ‘truth’ of the engulfing flatness of the ground.60

For Newman, then, the disclosure of the infinite is related to the dispelling of painterly illusion. But it is important to recall that the painter was also keen to represent the quest for the ‘impossible’ in religious terms. The Romantic spectre of ‘split religion’ thus comes to haunt the Greenbergian credo of pure abstraction.61 From the mid-1940s onwards, the titles that Newman chose for his works reflect his developing interest in the Old Testament, the Talmud and Jewish mysticism. Titles such as Genesis – The Break 1946, The Command 1946–7, Joshua 1950 and Adam 1950–1 leave no doubt in the mind that Newman regarded the sublime as primarily religious in orientation. His use of vertical lines or ‘zips’ – possibly inspired by Edmund Burke’s suggestion that the ‘perpendicular has more force in forming the sublime, than an inclined plane’ – can also be read as an echo of the primal act of divine creation.62 As the artist’s friend and commentator Thomas B. Hess noted, Newman claimed that the artist, like God, begins only with chaos, the void. The artist’s first move is thus to re-enact God’s primal gesture by informing the void with a downward stroke, analogous to ‘a gesture of separation, as God separated light from darkness, with a line drawn in the void’ – just as the emptiness of the Thing is said by Lacan to be informed by the intervention of the Symbolic.63

In ‘The Sublime is Now’, Newman, while fully aware of the religious cognates of his work, urges contemporary artists to free themselves from ‘the impediments of memory, association, nostalgia, legend [and] myth ... Instead of making cathedrals out of Christ, man, or “life”, we are’, he insists, ‘making it out of ourselves, out of our own feelings’.64 The subject matter of Newman’s work is thus ‘creation itself’, an act associated no longer with God but with man. Ultimately, the terrifying or overwhelming aspects of Newman’s paintings become subordinate to the idea of sustaining the distinction between form and formlessness. As Newman stated, after visiting the sacred mounds of the Native Americans in south-west Ohio: ‘Looking at the site you feel, Here I am, here ... and out beyond there (beyond the limits of the site) there is chaos ... but here you get a sense of your own presence ... I became involved with making the viewer present: the idea that “Man is present”.’65

Barnett Newman 1905–1970

Eve 1950

Oil on canvas

support: 2388 x 1721 x 50 mm

Tate T03081

Purchased 1980

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2002

Fig.9

Barnett Newman

Eve 1950

Tate T03081

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2002

What Lyotard intends with his conception of the ‘here and now’ in Newman is difficult to determine with any precision, but what he seems to have in mind is a disruptive, unrecuperable and above all ‘inhuman’ notion of temporality as pure difference. In ‘The Sublime and the Avant-Garde’ (1984) Lyotard maintains that for Newman the sublime resides not ‘in an over there, in another world, or another time, but in this: in that (something) happens ... the “it happens” is the paint, the picture’.69 The sublime, in other words, is the ‘event’ of the picture, what we might call its material occurrence. Writing in The Inhuman: Reflections on Time (1988) on the relation between painting and matter, Lyotard defines matter as a ‘presence [that is] unpresentable to the mind’.70 When painterly matter insists on the mind, the viewer thus experiences a disorientating, excessive mode of sublimity far removed from the Romantic notion of transcendence.

Lyotard’s comments in this respect recall his earlier observations on Cézanne and the unveiling of the figure. Earlier in this essay I noted how Cézanne’s interest in the ‘virginity of the world’ concealed a latent fascination with the death drive. The vivacity of Cézanne’s brush marks, I suggested, ought not to be understood as a phenomenological disclosure of the living world but rather as an indicator of the haunting return of the death drive in the guise of the Symbolic order. Similarly, with Newman, a more accurate examination of the relation between time and subjectivity can be gained from a consideration of Lacan’s observations on time and symbolisation. Noting in his 1955 seminar that ‘the percepi of man can only be sustained within a zone of nomination’, Lacan goes on to claim that the ‘word doesn’t answer to the spatial distinctiveness of the object ... but to its temporal dimension’. The object, he states,

is strictly only recognisable through the intermediary of the name. The name is the time of the object. Naming constitutes a pact, by which two subjects simultaneously come to an agreement to recognise the same object. If the human subject didn’t name – as Genesis says it was done in earthly Paradise ... no word, not even a perception, could be sustained for more than one instant.71

That is, it is only through the intervention of time and the word that subjects are rescued from the formlessness of the pre-symbolic. Newman’s ‘here and now’ can thus be read in relation to the dream of Irma’s injection: just as the spatial fixity of the Real is displaced in Freud’s dream by the narrative continuity afforded by entry into the Symbolic, so the zip in conjunction with the name (Abraham 1949, Onement III 1949, Cathedra 1951, Jericho 1968–9) places the viewer in relation to an Idea-Thing persisting beyond the field of representation.

What is repressed, of course, in Newman’s pursuit of the sublime and his denigration of beauty is the hidden domain of sexuality. Far from eradicating ‘the lure of the hidden (the feminine “other”)’, as Battersby has argued, I would suggest that Newman’s ‘terror’ in the face of the blank ground is directly related to the fear of the absence of vaginal depth portrayed in Duchamp’s Étant donnés.72 But whereas Duchamp sets out to cultivate anxiety by forcing the viewer to reflect on her/his complicity in the sexualised power dynamics of the gaze, for Newman the threat of the abyssal ground is countered by the entry into symbolisation. As a result of this intervention the viewing subject is placed in a relation with the abyss; the waste that lies ‘beyond the limits of the site’ and that threatens to overwhelm the subject is bounded, given form, by the line. The zip, together with the name, thus enables the viewing subject to sublimate the formlessness of the Real and to orientate her- or himself in relation to a transcendental beyond. The matter, which Lyotard regards as ‘unpresentable’, turns out, after all, to be mater, the principle of female abjection against which the subject is symbolically defined.

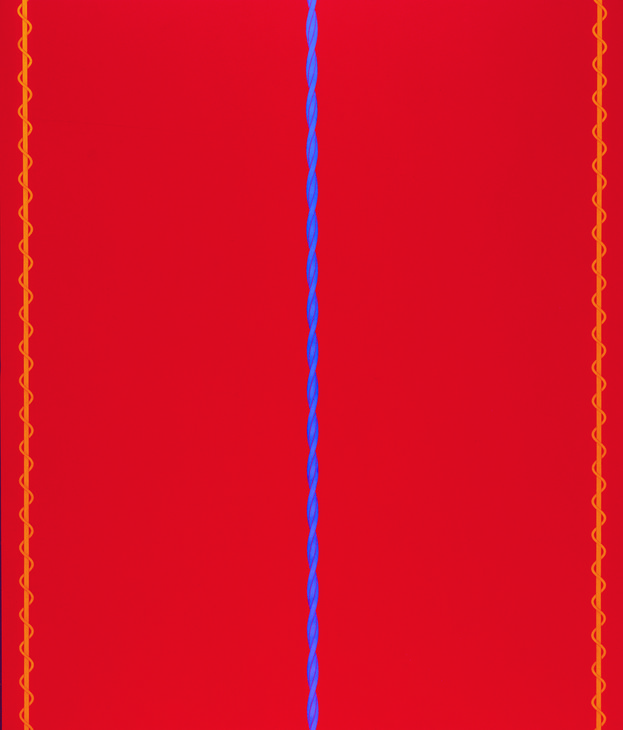

There is, as Napoleon suggested, and as Duchamp and Lacan imply, but a step from the sublime to the ridiculous. What happens, therefore, when Newman is unzipped? By way of an answer we may consider a recent postmodernist intervention by Philip Taaffe. In We Are Not Afraid 1985 (fig.10), a response to Newman’s Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue? 1966, Taaffe replaced the zip with a plaited braid of hair, rendered in blue and placed in the dead centre of the canvas. To the extreme left- and right-hand sides of the painting the artist introduced two snaking lines of yellow. The overall effect is decorative, even beautiful – a détournement of Newman’s sublimity brought about through a recollection of Henri Matisse’s bronze sculpture Back (IV) c.1931, which shows a long braid passing into the gap at the bottom of a monumental nude female torso. Poised between abstraction and figuration Matisse’s sculpture, with its own recollection of Cézanne’s female bathers, thus becomes a reminder of the material limits on which the image of the masculine sublime is raised.

In a reading of Taaffe’s painting, the scholar Lisa Liebmann observes how the twisted yellow lines on the extreme edges of the painting resemble the caduceus, the snake-entwined staff borne by the ancient Greek god Hermes (Mercury in Roman mythology). Liebmann states that the ‘mythic caduceus ... is a sexualized symbol, indeed a confluence of carnality and the sublime’.73 According to one Greek myth of origin, the caduceus was created when Tiresias killed a female snake after he had discovered it copulating with its mate. As a result of his action, Tiresias was transformed into a woman. He was turned back into a man when he was able to kill the male snake seven years later. As such, the appearance of the caduceus in Taaffe’s ‘answer’ to Newman becomes a symbol of the labile distinction between the sublime and the beautiful, the masculine and the feminine, the mind and the body. Neither one thing nor the other, Taaffe’s ‘zips’ speak of the impossibility of sustaining the sublime as pure abstraction.

The abject sublime

From Malevich to Newman, the struggle to overcome the accretions of the material realm is typically understood in theological terms. In America in the 1960s, the critic Robert Rosenblum, in his influential essay ‘The Abstract Sublime’ (1961), made explicit the connections between the religious imperatives of Romanticism and the transcendental aspirations of abstract expressionism. Drawing comparison between paintings by the Romantic painters Caspar David Friedrich and J.M.W. Turner and the abstract expressionist Rothko, Rosenblum claimed that ‘the floating, horizontal tiers of veiled light in the Rothko seem to conceal a total, remote presence that we can only intuit and never fully grasp. These infinite, glowing voids carry us beyond reason to the Sublime; we can only submit to them in an act of faith and let ourselves be absorbed into their radiant depths’. Following a discussion of Newman, Rosenblum announces that while in ‘the Romantic era, the sublimities of nature gave proof of the divine’, in the mid-twentieth century ‘such supernatural experiences are conveyed through the abstract medium of paint alone’.74

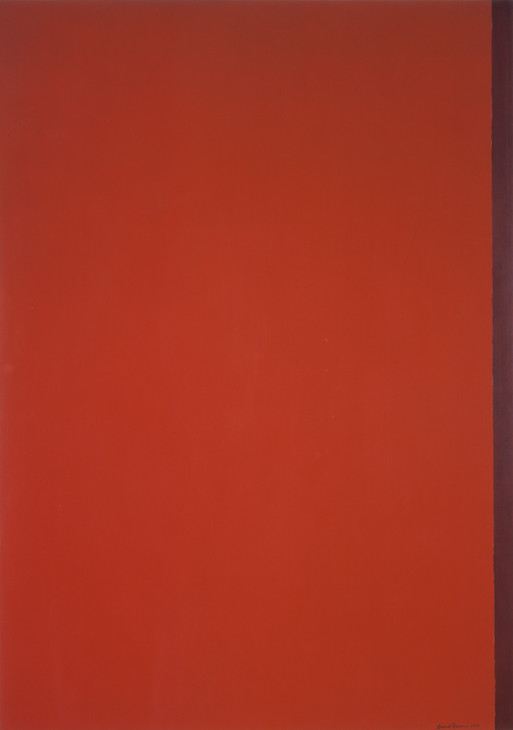

Mark Rothko 1903–1970

Red on Maroon 1959

Mixed media on canvas

support: 2667 x 2388 x 35 mm

Tate T01165

Presented by the artist through the American Federation of Arts 1969

© Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko/DACS 1998

Fig.11

Mark Rothko

Red on Maroon 1959

Tate T01165

© Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko/DACS 1998

But what precisely are we meant to see in this space? As the scholars Leo Bersani and Ulysse Dutoit observe, although ‘the internal frame’s repetition of the canvas’s verticality’ creates ‘an impression of depth’, the desire for legibility is ultimately frustrated. Due to the difficulty we experience in trying to distinguish between foreground and background – at times the silver-grey section appears to resist its subordinate position ‘so that it almost appears to be on the same plane as the red frame’ – the viewer may well come away with the impression that there is, after all, nothing to see in this work.75 Thus, while on the one hand the painting seems to encourage a revelatory response, akin in many ways to the effect of the Romantic sublime in works by Turner, of whom Rothko was a great admirer, it works no less to baffle or block such a response. The contest between the transcendental and the materialist aspirations of the painting results in what Bersani calls an effect of ‘narrative suspense’; unlike, say, Turner’s Angel Standing in the Sun 1846, or indeed Newman’s Vir Heroicus Sublimis 1950–1, in the face of this work it becomes impossible to sustain the sense of a determinate beyond.

In this respect it is worth considering the effect of scale. Measuring 2667 x 2388 mm, Red on Maroon, by any standard, is extremely large. ‘To paint a small picture’, Rothko once commented, ‘is to place yourself outside your experience. However you paint the larger picture, you are in it. It isn’t something you command.’76 When enclosed in the windowless, claustrophobic space of the Seagram room, the viewer may well feel similarly overwhelmed. In his later works, particularly the Houston Chapel series and the grisaille paintings of his final phase, Rothko goes even further in equating the effects of scale and obscurity with the defeat of spiritual significance. In such works the force of the sublime seems utterly disabling; in an instant the impulse towards transcendence is both raised and dashed. ‘Often, towards nightfall’, Rothko confessed, ‘there’s a feeling in the air of mystery, threat, frustration – all of these at once. I would like my painting to have the quality of such moments.’77

Rothko famously insisted that his work was an attempt to express ‘basic human emotions – tragedy, ecstasy, doom’.78 Something of Nietzsche’s interest in the Apollonian veiling of terror, in the ability of art to render terror bearable, seems implicit in this statement. If the artist or the viewer seeks to go beyond the frame of the Symbolic, then she or he does so at their peril. However, as Lacan noted, when the subject is delivered from the threat of the Real then he or she submits, in turn, to a form of gentrification in which the tragic dimension is diminished. In the Seagram series, Rothko, I would argue, holds the tragic and comedic aspects of the sublime encounter in delicate suspension. The viewer is simultaneously attracted to and safely delivered from the overwhelming terror of the abyssal ground.

By way of a conclusion to this essay I wish to place Rothko’s later work in relation to an artist whose work appears, on the face of things, to have little to do with the sublime: Francis Bacon. With his stress on viscosity, on the raw, material ooze of embodied experience, Bacon seems to block the route to transcendence that is the dominant aspiration of abstract painting. In an important review of Gilles Deleuze’s Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation (1981) the literary critic Allon White comments on ‘Bacon’s radical refusal of transcendence – a firm refusal of narrative and a refusal of sublimation. There is a kind of material resolution in the paintings, which amounts to a modern heroism, not to allow conventional beauty to obliterate or falsify the moments of abjection which permeate daily life’.79 Unlike Taaffe, whose work connives to unsettle the sublime by reframing it in terms of the beautiful, Bacon sets out to destroy the sublime through a violent immersion in abject matter. Kristeva, as we have seen, notably defines the abject as that which ‘does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite’.80 When Bacon introduces the abject into his paintings he thus destabilises the very distinctions on which the sublime is raised.

Mark Rothko 1903–1970

Untitled 1969

Acrylic on paper

support: 1730 x 1235 mm

Tate T04149

Presented by the Mark Rothko Foundation 1986

© Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko/DACS 1998

Fig.12

Mark Rothko

Untitled 1969

Tate T04149

© Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko/DACS 1998

Bacon’s use of a thick, impenetrable field of black underscored by an equivalent field of grey has obvious connections with Rothko’s late work. But between these monochromatic fields Bacon has inserted a horizontal band of mottled grey-beige on which he has painted a vivid, ruddy pool – the blood on pavement of the title. Whatever remained of the transcendent in Rothko’s painting is completely obliterated with the introduction of this ugly, anamorphic stain. In imitation of Rothko’s earlier work, the red mark seems to hover on the surface of the painting; but rather than providing an intimation of immortality, it serves instead as a memento mori. Like Whistler’s body/barge, Courbet’s grotto or Cézanne’s stroke, Bacon’s blood is unsettling because it occupies the middle ground, disturbing the boundary between subject and object. As a sublime object in the Lacanian sense, the stain inhabits neither the body nor the world; rather, it resides in a space between, resisting all attempts to convert it into the material Other of an infinite beyond.

Conclusion

It has been the contention of this essay that art of the late nineteenth century and of the first half of the twentieth century sustains an uneasy and at times fraught relation with the sublime: just as Nietzsche laboured against the stultifying legacy of the Kantian tradition, so modern artists struggled with the persistence of Romanticism. In their attempts to reformulate an idea of the sublime object, artists as varied as Whistler and Malevich, Cézanne and Duchamp, found themselves engaged in dialogue with their Romantic forebears. Central to each of their endeavours was the cultivation of a sceptical attitude towards ideas of transcendence, particularly in connection with modes of the sublime that sought to denigrate or repress the claims of human experience, whether conceived as the raw materiality of the body, the ‘terror’ of sexuality, or the unsettling otherness of the unconscious. If Nietzsche is responsible for the initial querying of the Kantian distinction between immanence and transcendence, it is Freud, and later Lacan, who ushers in and oversees the radical transformation of this distinction. The Nietzschean/Freudian influence, as we have seen, is notable in dada, surrealism and abstract expressionism. Specifically, it emerges in Duchamp’s dogged assaults on the conceptual purity of the art object, in Magritte’s wry exposures of the illusory nature of the gaze, in Rothko’s haunted meditations on the impossibility of transcendence, and in Bacon’s singular insistence on the brutish reality of human experience. In each case, an idea of the sublime is raised, only to be mocked, interrogated, mourned and finally torn to pieces.

Such a nihilistic conclusion requires, however, some additional commentary. In The Fragile Absolute, Zizek explains that in contemporary art the idea that one can raise an object, whether it be blood (Marc Quinn, Self 1991), faeces (Chris Ofili, The Holy Virgin 1996), a pair of dead cows (Damien Hirst, Mother and Child Divided 1993) or yet another urinal (Sarah Lucas, The Old in Out 1998) to ‘the dignity of the Thing’ seems to be increasingly under threat: ‘what is threatened is the very gap between the empty Place and the (positive) element filling it’. If the problem for ‘premodern’ art was

how to fill in the sublime Void of the Thing (the pure Place) with an adequately beautiful object ... [then] the problem of modern art is, in a way, the opposite (and much more desperate) one: one can no longer count on the Void of the (Sacred) Place being there, so the task is to sustain the Place, as such, to make sure that the Place itself will ‘take place’ – in other words, the problem is no longer that of horror vacui, of filling in the Void, but, rather, that of creating the Void in the first place.85

When in the sacred space of the gallery we stare at the piece of dead, inert matter, asking indignantly ‘is this art?’, it is, as Zizek observes, ‘precisely this negative reaction, this experience of the radical incongruity between the object and the Place it occupies, that makes us aware of the specificity of this Place’. It is, therefore, not only ‘the Place it occupies that confers sublime dignity on an object; it is also that only the presence of this object sustains the Void of the Sacred Place, so that the Place itself never takes place, but is always something which, retroactively, “will have taken place” after it has been disturbed by a positive element’. In ontological terms, if we remove from the Void the ‘little bit of reality’, the bloodstain that upsets its stability, we do not encounter the pure Void ‘as such’ – ‘rather, the Void itself disappears, is no longer there’. Paradoxically, therefore, it is the presence of the abject object that sustains the idea of the sublime.86

In recent years Zizek’s neo-Lacanian account of the sublime has been examined and found wanting by the theologian John Milbank – directly in an essay entitled ‘Sublimity: The Modern Transcendent’ (2004), and implicitly in a book co-authored with Zizek entitled The Monstrosity of Christ (2009).87 There is not the space here to discuss the finer details of Milbank’s critique of Zizek’s insistence on modern art as a manifestation of the fundamental emptiness of being, but in closing this essay some mention should be made of Milbank’s discussion of the sublime, at least in its Kantian and post-Kantian forms, as a fundamental perversion of the beautiful. Whether conceived as a transcendental beyond or as a brute manifestation of primal nothingness, the modern, secular notion of the sublime fails, in Milbank’s view, to take account of the analogical relation between the finite and the infinite, whereas beauty, especially when regarded from a Christian and more specifically Catholic perspective, retains a sense of the continuity between the human and the divine, the particular and the general, the reality and the idea.

In this essay I have suggested that the religious sublime, originating in Romanticism and reanimated in abstract expressionism is unable to withstand the challenge of a form of post-Duchampian, abject materialism, loosely identified with surrealism, art informel, neo-dada and, most recently, with the neo-conceptualists and the Young British Artists. An alternative account of the development of the sublime could, however, take its bearings not from abstract expressionism, but from minimalism and the Earthworks movement. In both cases artists have emerged whose interest in the relations between matter and spirituality could be said to mark an advance on traditional notions of the sublime. In James Turrell’s light works, for example, viewers are placed in concrete situations – a volcanic crater, an observation chamber – that encourage habits of sustained concentration. Drawing on what Turrell calls the Quaker’s ‘straightforward, strict presentation of the sublime’, the ‘plumbing of visual space through the conscious act of moving, feeling out through the eyes’ becomes ‘analogous to ... a flight of the soul’.88 As the curator Lynn M. Herbert summarises: ‘Turrell’s sublime is compounded as we observe ourselves seeing. He allows us to look at light in such a way that we can see into ourselves through the universe beyond.’89 Environmental art by Robert Smithson, Walter De Maria and, most recently, Olafur Eliasson, endeavours similarly, with varying degrees of faith and scepticism, to reconfigure the viewer’s relationship with space and time, placing emphasis on the connections between the material conditions of perception and the intuition of an immaterial beyond.90

The Protestant legacy, with its stress on unmediated vision, plainness and individual autonomy, is evident in those artworks that seek to place the viewer in close proximity to natural sources of wonder. Catholicism, with its emphasis on mystery, transfiguration and the effacement of self in the face of the divine has brought about an altogether different notion of the sublime. In Yves Klein’s photomontage Leap into the Void 1960, for instance, the artist appears to take flight from an ordinary suburban window as, below him, a cyclist meanders along a circumscribed road. The image, as the scholar Jean Fisher comments, with its unsettling blend of the impossible and the mundane suggests ‘an “embodiment” of the metaphysical union of flesh with the infinite’.91 The notion of the congruence of the earthly and spiritual is most vividly conveyed in the form of the casket that Klein, a devout Catholic, donated to the convent of Santa Rita da Cascia in 1961. Consisting of three compartments containing IKB (International Klein Blue) pigment, pink pigment and gold ingots, the work is dedicated to ‘Santa Rita da Cascia, Saint of Impossible and desperate causes’. For Fisher, ‘Klein’s simple but elegant presentation of the sheer vibrancy of colour and light through the raw materiality of pigment and gold is one of the clearest attempts in art to evoke that transformative immateriality, that fugitive moment of lightness and ecstasy, to which mystic speech so often refers’.92 The work is sublime, in other words, because the transformation of pigment into divinity is impossible; yet still, for those who believe, the ‘fugitive moment’ takes place. As the early Christian author Tertullian put it: ‘sepultus, resurrexit; certum est, quia impossibile’ ([Christ] was buried and rose again: it is certain [or ‘I believe’] – because it is impossible).93

It may be that sublimity consists in nothing more than ‘the movement of desire’: in our desire to know what is beyond the painted veil; in the ‘feeling that something “lost” must be recovered’. And yet, as Fisher concludes, ‘if the language of art seeks to imagine unity it can only discover its impossibility, becoming, in effect, “an affirmation of alterity”’.94 Looking again at Bacon’s bloodstain, for instance, might we not also see the remnants of divine incarnation – of the body that remains when God is denied? And might this impossibility not also be configured as a paradoxical ‘affirmation of alterity’? Perhaps, in this sense, Bacon’s vision of the abject sublime is closer in spirit to a ‘premodern’ work, such as Masaccio’s Holy Trinity 1427, with its moving portrayal of human as well as divine agony, than it is to the suave sardonicism of dada and surrealism or the gleeful fatalism of the YBAs. In the end, however, Masaccio’s work, unlike Bacon’s, is literally inscribed on the walls of the Sacred Place – the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence – a place conceived not as horror vacui but as a beautiful space of plenitude and becoming. This difference is insurmountable.

Notes

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, ‘The Ten O’Clock’, in Mary Ann Caws (ed.), Manifesto: A Century of Isms, Lincoln 2001, p.7.

It is worth noting that during the 1860s reports of accidental deaths, murders and suicides associated with the Thames increased threefold. In June 1870 an article in the Penny Illustrated Paper claimed that ‘[d]eaths by drowning occur almost daily in the Thames’ (25 June 1870). Whistler, a resident of Chelsea, would have been aware of this fact and he may well have known of the ‘Mysterious Death Of A Lady’s Maid’, reported in Reynolds’s Newspaper on 18 June 1871. The victim, a twenty-one-year-old woman named Elizabeth Slyfield, was seen by a waterman throwing herself into the river at Battersea on the morning of 31 May; a verdict of felo-de-se was entered by the coroner to East Surrey two weeks later. The report concludes ‘[the deceased] had not been seduced ... [she] destroyed her own life while of unsound mind’.

The sense in which the subject is ‘photo-graphed’ by the gaze of the ‘Other’ is explored by Jacques Lacan in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, ed. by Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. by Alan Sheridan, London and New York 1998, p.106.

The movement from the Romantic sublime to the modernist uncanny is explored by David R. Ellison in Ethics and Aesthetics in European Modernist Literature: From the Sublime to the Uncanny, Cambridge 2001. See p.53.

The uncanny effect of the anamorphic skull depicted in Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors 1533 (National Gallery, London) is discussed by Lacan in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, p.92. For further discussion of anamorphosis, see Jacques Lacan, The Ethics of Psychoanalysis, ed. by Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. by Dennis Porter, London 1992, pp.135–6, 140–1, 272–3.

Friedrich Nietzsche, ‘Preface’, The Gay Science, trans. and ed. by Walter Kaufmann, New York 1974, §4.

By contrast, Martin’s earlier work, such as The Creation 1824, offers a more disorientating impression of the divine. As the Edinburgh Review commented in 1829, Martin’s work ‘awakes a sense of awe and sublimity, beneath which the mind seems overpowered’. Cited by Robert Rosenblum in ‘The Abstract Sublime’ (1961); extract reprinted in Simon Morley (ed.), The Sublime, Cambridge, Massachusetts 2010, p.110.

James Elkins, On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art, Abingdon and New York 2004, p.96.

Neil Hertz discusses Courbet’s painting in The End of the Line: Essays on Psychoanalysis and the Sublime, Aurora 1985, pp.246–50.

See http://www.musee-orsay.fr/index.php?id=851&L=1&tx_commentaire_pi1%5BshowUid%5D=125&no_cache=1 , accessed 12 September 2012.

Slavoj Zizek, The Fragile Absolute – Or, Why is the Christian Legacy Worth Fighting For?, London and New York 2000, pp.37–8. In 1955 the painting was sold at auction for 1.5 million francs. The purchaser was Jacques Lacan.

For a detailed defence of the Lacanian theorisation of sexual difference, see Slavoj Zizek, ‘Connections of the Freudian Field to Popular Culture’, Interrogating the Real, ed. by Rex Butler and Scott Stephens, London and New York 2008, pp.63–9.

Friedrich Nietzsche, ‘On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense’, Philosophy and Truth: Selections From Nietzsche’s Notebooks of the Early 1870s, trans. and ed. by Daniel Breazeale, Atlantic Highlands, 1994, p.83. Quoted in Battersby 2007, p.188.

For a representative view, see Maurice Merleau-Ponty, ‘Cézanne’s Doubt’, Basic Writings, (ed.) by Thomas Baldwin, London 2003, pp.271–89.

Michael Doran (ed.), Conversations with Cézanne, trans. by Julie Lawrence Cochran, Berkley, Los Angeles and London 2001, p.114.

John Keats, letter to George and Tom Keats, 21 December 1817, in The Letters of John Keats, ed. by Robert Gittings, Oxford 1987, p.43.

T.J. Clark, ‘Phenomenality and Materiality in Cézanne’, in Tom Cohen (ed.), Material Events: Paul de Man and the Afterlife of Theory, Cambridge, Massachusetts 2001, pp.93–113.

Jean-François Lyotard, Discourse, Figure, trans. by Antony Hudek and Mary Lydon, Cambridge, Massachusetts 2010.

Jacques Lacan, The Ego in Freud’s Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis, 1954–1955, ed. by Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. by Sylvana Tomaselli, New York and Cambridge 1988, p.326.

For further discussion of abjection in modern art, see Yve Alain-Bois and Rosalind E. Krauss, Formless: A User’s Guide, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1997.

Kazimir Malevich, ‘The Non-Objective World: The Manifesto of Suprematism’ (1926), in Caws 2001, p.404.

Quote taken from Margarita Tupitsyn, ‘“Black Square: Hommage a Malevich”; Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg’, Artforum, September 2007, at http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_1_46/ai_n28045905/ , accessed 25 March 2010.

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgement, trans. by Werner S. Pluhar, Indianapolis and Cambridge 1987, p.135.

See http://www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?criteria=O%3AAD%3AE%3A3692&page_number=1&template_id=1&sort_order=1 , accessed 12 September 2012.

Slavoj Zizek, Tarrying With the Negative: Kant, Hegel, and the Critique of Ideology, Durham 1993, p.103.

Amelia Jones, Postmodernism and the En-Gendering of Marcel Duchamp, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994, p.200.

Artist cited in Exhibition Catalogue, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Lucio Fontana, Venice and New York, New York 2006, p. 19

Barnett Newman, ‘The Sublime is Now’, Barnett Newman: Selected Writings and Interviews, ed. by John Philip O’Neill, Berkeley 1990, pp.172–3.

Pierre Schneider, ‘Flat Forms, Deep Thoughts; Newman on Géricault’, in Melissa Ho (ed.), Reconsidering Barnett Newman, Philadelphia 2005, p.136.

The phrase is taken from T.E. Hulme’s 1924 essay ‘Romanticism and Classicism’, The Collected Writings of T.E. Hulme, ed. by Karen Csengri, Oxford 1994, pp.61–2.

Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful and Other Pre-Revolutionary Writings, ed. by David Womersley, London 1998, p.114.

See Caroline A. Jones, Machine in the Studio: Constructing the Postwar American Artist, Chicago and London 1996, pp.44–51.

Jean-François Lyotard, The Inhuman: Reflections on Time, trans. by Geoffrey Bennington and Rachel Bowlby, Polity Press, Cambridge 1993, p.90.

Jean-François Lyotard, ‘The Sublime and the Avant-Garde’, trans. by Lisa Liebmann, Artforum, vol.22, no.8, April 1984, pp.36–43.

Lisa Liebmaan, ‘Philip Taaffe: Romancing the Figure’, in Philip Taaffe, exhibition catalogue, Thomas Ammann Fine Art, A.G., Zurich 1998, http://www.philiptaaffe.info/Critical_Commentary/LisaLiebmann.php , accessed 25 March 2010.

Leo Bersani and Ulysse Dutoit, Arts of Impoverishment: Beckett, Rothko, Resnais, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London 1993, p.123.

David Sylvester, ‘The Ugly Duckling’, in Michael Auping (ed.), Abstract Expressionism: The Critical Developments, exhibition catalogue, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo 1987, p.140.

Allon White, Carnival, Hysteria and Writing: Collected Essays and Autobiography, Oxford 1993, p.161.

See http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/francis-bacon/room-guide/room-9-epic/room-10-late , accessed 12 September 2012.

Achim Borchardt-Hume, ‘Shadows of Light: Mark Rothko’s Late Series’, in Rothko, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2008, pp.25–6.