Henry Moore OM, CH Half-Figure 1932

Image 1 of 10

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Half-Figure 1932© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Half-Figure

1932

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

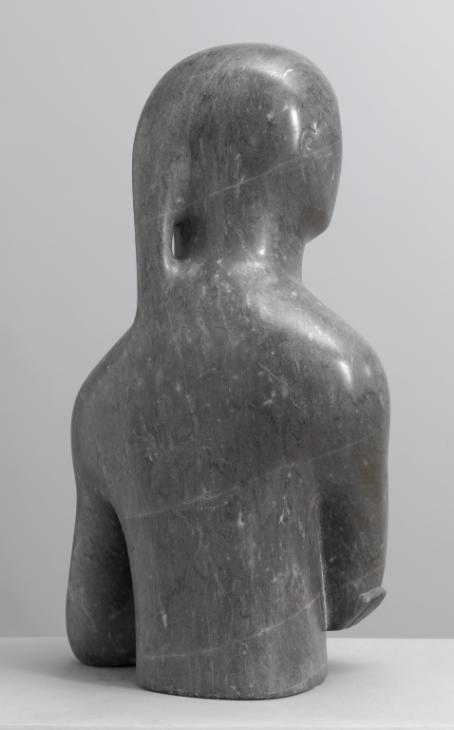

Half-Figure 1932 is one of several sculptures of half-length adolescent female figures carved by Henry Moore between 1929 and 1932. It is an example of Moore’s early commitment to direct carving, while the pose of the figure reveals his interest in non-Western sculpture. It is also historically important as an early example of Moore’s use of holes in sculpture.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Half-Figure

1932

Armenian marble

686 x 381 x 279 mm

Bequeathed by E.C. Gregory 1959

T00241

Half-Figure

1932

Armenian marble

686 x 381 x 279 mm

Bequeathed by E.C. Gregory 1959

T00241

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist through the Leicester Galleries by E.C. Gregory, London, in 1933, by whom bequeathed to the Tate Gallery in 1959.

Exhibition history

1932

?Sculpture Considered Apart from Time and Place, Sydney Burney Gallery, London, November 1932, no.8 (as ‘Woman’).

1933

Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, Leicester Galleries, London, November 1933, no.12 (as ‘Woman’).

1946–7

Henry Moore, Museum of Modern Art, New York, December 1946–March 1947; Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, April–May 1947; San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco, July–August 1947, no.20 (as ‘Figure’).

1947–8

Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, 1947–8, no.3.

1949

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings (1923–1948), Wakefield City Art Gallery, Wakefield, April–May 1949, Manchester City Art Gallery, Manchester, June–July 1949, no.24 (as ‘Figure’).

1949

Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, October 1949; Musée d’art moderne, Paris, December 1949; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, January 1950; Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, March 1950; Städtische Kunstsammlungen, Düsseldorf, May 1950; Kunsthalle Berne, Berne, June–July 1950, no.18 (as ‘Figure’).

1952

Seventeen Collectors, Contemporary Art Society, London, March–April 1952, no.81 (as ‘Figure’).

1953–4

Henry Moore: Ausstellung von Plastiken und Zeichnungen veranstaltet vom British Council, British Council touring exhibition: Bayerischen Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich; Staedel Institut, Frankfurt; Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart; Kunsthalle Mannheim, Mannheim, Kunsthalle Bremen, Bremen; Stadtverwaltung, Gottingen; Kestner-Gesellschaft, Hannover, 1953–4, no.2.

1955

Twentieth Century Paintings and Sculptures Lent by Collectors in England, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, June–July 1955, no.21 (as ‘Figure’).

1959

A Selected Exhibition from the Collection of the Late E.C. Gregory, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, July–August 1959, no.55 (as ‘Head and Shoulders of a Woman in Stone’).

1973

Henry Moore to Gilbert & George: Modern British Art from the Tate Gallery, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, September–November 1973, no.26.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, Palacio de Velázquez, Palacio de Cristal, Parque de El Retiro, Madrid, May–August 1981, no.21.

1981

Henry Moore, Fundacão Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, September–November 1981, no.13.

1982–3

Henry Moore: Early Carvings 1920–1940, Leeds City Art Gallery, Leeds, November 1982–January 1983, no.29.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983, no number.

1988

Henry Moore, Royal Academy of Arts, London, September–December 1988, no.18.

1993–4

Herbert Read: A British Vision of World Art, Leeds City Art Gallery, Leeds, November 1993–February 1994, no.140.

1998

Carving Mountains: Modern Stone Sculpture in England 1907–37, Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, March–April 1998; De la Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, May–June 1998, no.35.

2001

Breaking the Mould: 20th-Century British Sculpture from Tate, Norwich Castle Museum, Norwich, July–September 2001, no.8.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no number.

2006

Henry Moore, Fundació ‘la Caixa’, Barcelona, July–October 2006, no number.

2010–11

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, October 2010–February 2011; Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, March–June 2011, no.28.

References

1934

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: Sculptor, London 1934, reproduced pls.25–6 (as Woman).

1944

Herbert Read (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, London 1944, reproduced pl.31b (as Woman).

1946

James Johnson Sweeney, Henry Moore, New York 1946, reproduced p.25 (as Figure).

1948

A.D.B. Sylvester, ‘The Evolution of Henry Moore’s Sculpture: I’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, no.543, June 1948, p.159.

1957

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, London 1957, p.8, no.117, reproduced p.68.

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, p.29, reproduced pl.12.

1960

Report of the Trustees for the Year 1 April 1959 to 31 March 1960, Tate Gallery, London 1960, pp.23–4, reproduced pl.5.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, London 1964, pp.454–5, reproduced pl.9.

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–69, London 1970, reproduced fig.71.

1982

Henry Moore: Early Carvings 1920–1940, exhibition catalogue, Leeds City Art Gallery, Leeds 1982, reproduced p.68.

1988

Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, pp.178–9.

1993

Benedict Read and David Thistlewood (eds.), Herbert Read: A British Vision of World Art, exhibition catalogue, Leeds City Art Gallery, Leeds 1993, reproduced fig.49.

1998

Sophie Bowness, ‘Modernist Stone Carving in England and “The Big View of Sculpture”’, in Carving Mountains: Modern Stone Sculpture in England 1907–37, exhibition catalogue, Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge 1998, p.35, reproduced p.53.

2001

Breaking the Mould: 20th-Century British Sculpture from Tate, exhibition catalogue, Norwich Castle Museum, Norwich 2001, reproduced p.16.

2005

Henry Moore y México, exhibition catalogue, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City 2005, reproduced p.79.

2005

Anne Wagner, Mother Stone: The Vitality of Modern British Sculpture, New Haven and London 2005, reproduced fig.10.

2006

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fundació ‘la Caixa’, Barcelona 2006, reproduced p.79.

2010

Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, reproduced p.114.

Technique and condition

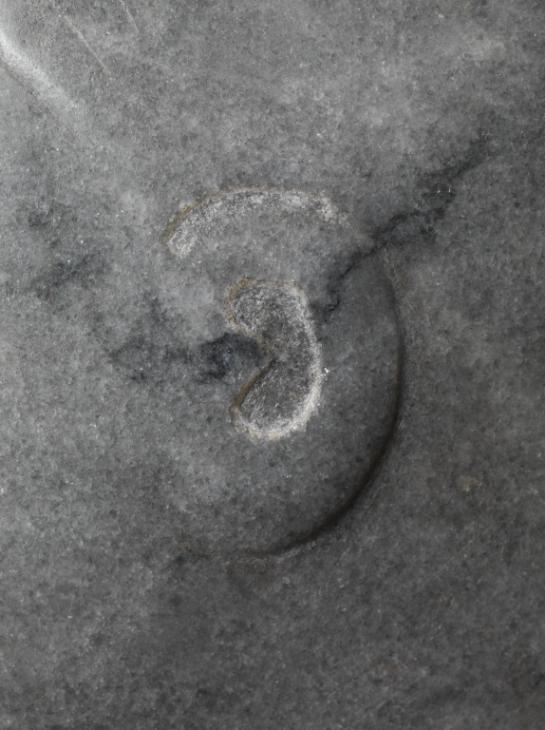

This sculpture presents the head and nude torso of a girl and is carved from grey Armenian marble. The surface has a smooth polished finish, and features incised lines and drilled holes denoting details such as the eyes, hair, nipples and thumbnails (fig.1). The sculpture does not have a base and rests directly on the plinth with only a very slight chamfer around the lower edge, possibly to prevent chipping during handling or to make a distinct line where the sculpture rests. A similar chamfered edge is seen on Moore’s sculpture Girl 1931 (Tate N06078).

Detail of Half-Figure 1932 showing incised eyes, drilled nostrils and mouth

Tate T00241

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of Half-Figure 1932 showing incised eyes, drilled nostrils and mouth

Tate T00241

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

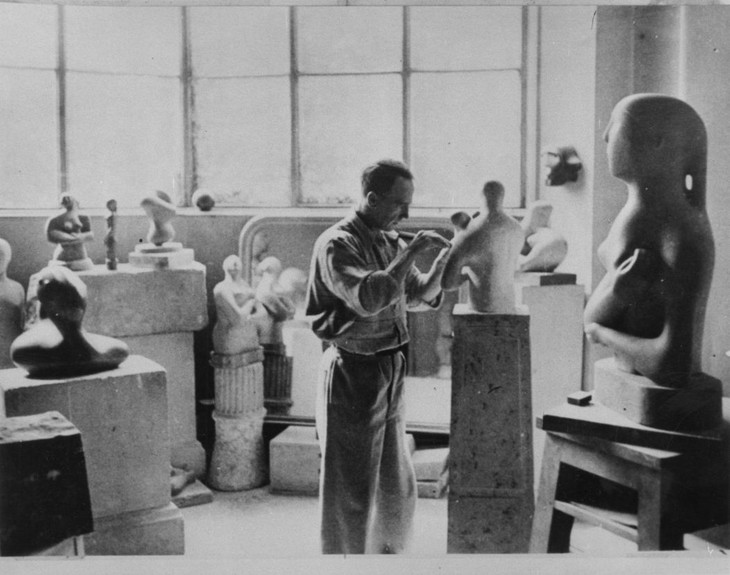

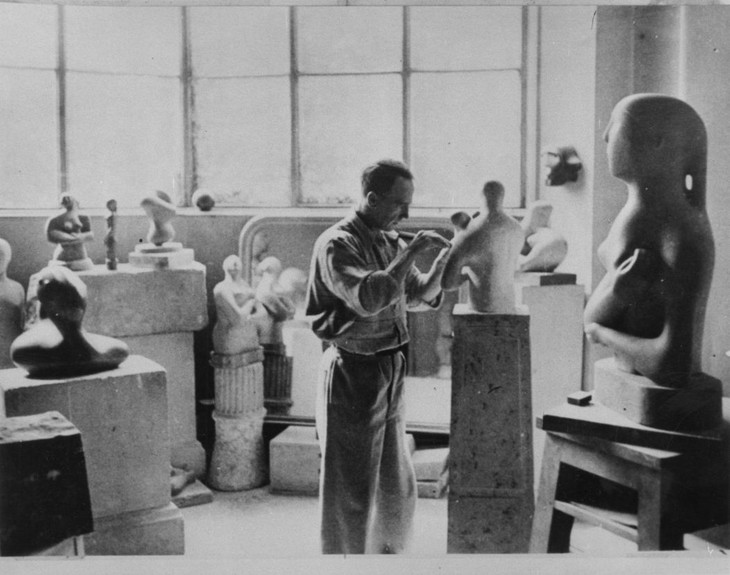

Henry Moore in his studio in 1932 with Half-Figure on original oval base

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Henry Moore in his studio in 1932 with Half-Figure on original oval base

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Photographs from Moore’s studio show that Half-Figure was originally displayed on a thick wooden oval base, possibly about ten centimetres deep (fig.2). However, by the time Tate acquired the sculpture this base had become damaged and was not subsequently shown with the work.

Moore carved the sculpture from a single block of marble. The form would have been roughed out using a hammer and chisels before being worked with progressively smaller chisel sizes to carve the finer details. Pierced areas at the back of the neck and at the girl’s left elbow may have been made using a drill. Eventually the shapes would have been smoothed with a range of files before being sanded and polished to give the final smooth finish.

There is no inscription but there is a small purple ink stamp on the base of the sculpture, approximately fifteen millimetres in diameter. The stamp may have contained letters but these are not clear enough to read. A similar stamp is seen on the underside of Moore’s Recumbent Figure 1938 (Tate N05387). It is likely that these stamps were applied after completion but it is not clear what they signify.

Lyndsey Morgan

October 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', October 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Half-Figure 1932 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, January 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

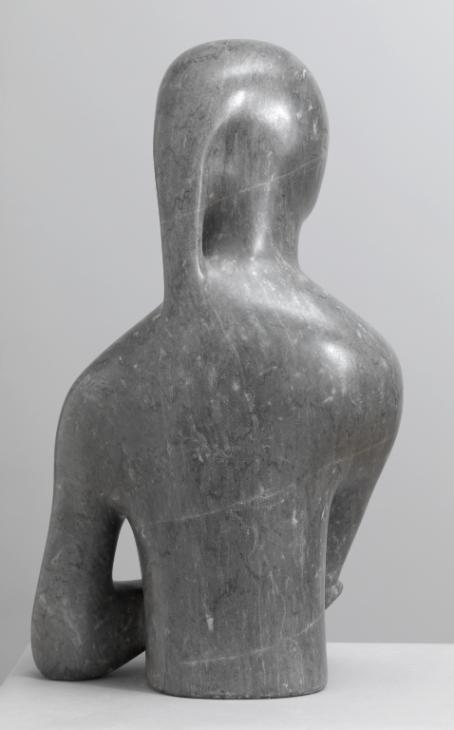

Henry Moore’s sculpture Half-Figure 1932 was carved in grey marble and presents the head, torso and arms of an adolescent girl. Cut at the waist, the nude female figure wraps her arms around her body, with her right hand cupping the side of her left breast, and her left hand supporting her right elbow. Her head is almost round and turns to the right, and her face is tilted so that her chin is slightly raised and her eyes look upwards. Her glance is alert, which suggests a sense of purpose and agency. She has thin and pinched or pursed lips, and her upturned nose is formed in the shape of a tetrahedron with two round shallow indents denoting nostrils. The concave eye sockets are each punctuated by a slightly raised area denoting the eyes. Each eye is illustrated with almond shaped incised lines, circles denoting the iris and a small round hole denoting the pupil. Eyebrows are rendered as a ridge that demarcates the concave orbits of the eyes, curving across the top of each eye and around the sides of the face, terminating at the cheekbones. The features of the face appear to have been pinched together and seem disproportionately small in proportion to the size of the face. She has a high forehead and spacious, smooth cheeks, a wide jaw-line and a large chin. Oval shaped ears have been carved in shallow relief, with a reversed C-shape denoting the ear canal. A slightly raised hairline can be discerned across the girl’s forehead, while her hair has been carved as though in a ponytail, which is gathered at the back of her head. When viewed from the side, it is clear that Moore carved a gap between the back of the girl’s neck and the hair, which falls parallel to her neck and merges with her left shoulder.

The figure’s shoulders are broad but asymmetrical, with the right slightly higher that the left, which is slightly longer. The breastbone is concave and the torso is tubular with two pert, small breasts. Nipples and areolas are represented by two incised concentric circles. Seen from the rear, the shoulders appear powerful although her upper arms are thin. The upper part of the right arm is held against the side of the torso, while the upper part of the left arm is held away from the body and bends at the elbow, which rests on the plinth. Although the fingers on both hands have been individually suggested, they are nonetheless conjoined, rendering the hands mitten-like.

Although the sculpture has a generally consistent, smooth surface, fine chisel marks can be seen under the left breast (fig.1). Moore created Half-Figure using the method of direct carving. This meant that he worked directly on the stone, using a range of chisels, rifflers and hammers, without the aid of preparatory sketches or maquettes (scale models made in clay or plaster). Moore and his contemporaries, including Barbara Hepworth and John Skeaping, believed that when carving directly into stone or wood to create a unique artwork, the form or shape of the final sculpture should evolve through the processes of its making. In 1934 Moore articulated the approach he had been taking in the early 1930s in his statement for the publication Unit One:

Every material has its own individual qualities. It is only when the sculptor works direct, when there is an active relationship with his material, that the material can take its part in the shaping of an idea. Stone, for example, is hard and concentrated and should not be falsified to look like soft flesh – it should not be forced beyond its constructive build to a point of weakness. It should keep its hard tense stoniness.1

Adhering to the methods of direct carving meant that the sculptor consciously respected the nature of the material and worked with it to bring out its particular properties, including its colour and surface texture. As a consequence, surface decoration or adornments were rejected in favour of uncluttered surfaces that emphasised the colour and veining of the stone. In Half-Figure Moore seems to have harnessed the white veining of the marble, which runs vertically and diagonally through the sculpture, in order to emphasise the downward directional pull of the shoulders. A white vein runs from the crown of the figure’s head down the left side of the face and neck to her sternum. Another vein runs diagonally across the face of the figure from her right forehead to the left part of the chin like a scar. Rather than attempt to make stone look like flesh, Moore believed that exploiting the inherent characteristics of the raw material would provide the sculpture with what he described as its ‘vitality ... an intense life of its own, independent of the object it may represent’.2

Moore’s use of grey Armenian marble for this work is unusual as most of his carvings from the late 1920s and early 1930s were created in English stones. Early in his career Moore had made a point of using native materials, which were not only cheaper than foreign stones, but rarely used for free-standing sculpture. In this way Moore challenged the conventions of sculpture, which had traditionally been carved in marble or cast in bronze. By using Armenian marble Moore may have been simultaneously seeking to demonstrate that his preference for direct carving could and should be pursued with more conventional sculptural materials while also differentiating himself from the Italian marbles commonly used for sculpture.

Henry Moore in his studio in 1932 with Half-Figure on original oval base

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Henry Moore in his studio in 1932 with Half-Figure on original oval base

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The different carving techniques visible in Half-Figure were also utilised by Hepworth in her Sculpture with Profiles 1932 (Tate T06520). This work, like Moore’s Half-Figure, contrasts smooth areas of stone with sharp incised lines. Both artists utilised a type of drawing on stone in order to suggest new ways of thinking about how stone might be carved and presented. Indeed, when Half-Figure was illustrated in Herbert Read’s book on Moore in 1934, the sculpture was represented by a full-view photograph and a detail of the hand cupping the breast. Early black and white photographs such as that reproduced in Read’s book show the incised lines with greater clarity than later reproductions. By highlighting the drawn nipple of Half-Figure through the photographic detail, Read implicitly demonstrated the way in which Moore refused to present the figure in an anatomically correct fashion – to make stone look like flesh – thereby subtly highlighting the ‘stony nature’ of his material.5

Although it is not known exactly when in 1932 Half-Figure was completed, it was included in Moore’s exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in November 1933. This was his second solo show at that gallery, having exhibited there in 1931, and he went on to have two more shows there in 1936 and 1940. Half-Figure was originally exhibited under the title Woman, but from 1946 was known as Figure. In 1959 it was displayed at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London under the descriptive title Head and Shoulders of a Woman in Stone. Since entering Tate’s collection the sculpture has been known as Half-Figure, which was the title given in the 1957 revised edition of Henry Moore’s catalogue raisonné.

Half-Figure was singled out in a review of the 1933 exhibition published in the Times. The unnamed critic noted that Moore’s sculpture fell into two categories, the figurative and the abstract, and stated that ‘attention goes most readily and sympathetically ... to works, like Woman in dove-grey Armenian marble’.6 The critic went on to identify that any deviation from natural exactness or accurate figuration in the work ‘appears to be determined by the character of the material and the requirements of composition’, rather than by any attempt to consciously deform the figure.7

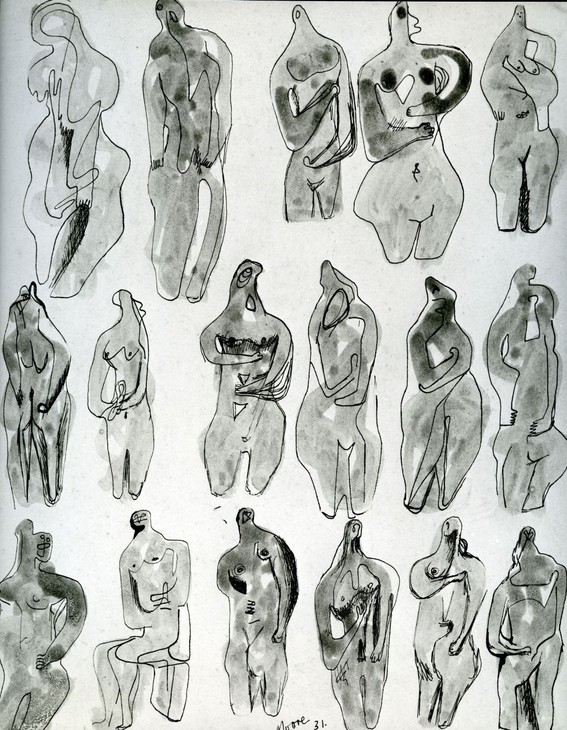

Although no preparatory drawings exist relating specifically to Half-Figure, between 1929 and 1932 Moore made numerous drawings of female half-figures, such as Studies for Sculpture 1931 (fig.3). On this page a series of figures are presented variously with their hands clasped together in front of their bellies, with their arms wrapped around their bodies, or as in the case of Half-Figure, with their hands cupping elbows and breasts. Drawings such as these are demonstrative of the ways in which Moore was experimenting with the formal possibilities of a figurative pose that considered the placement of arms and hands. Cumulatively, it is probable that Moore’s sketches helped him to clarify the composition of his sculptures of female figures.

Henry Moore

Studies for Sculpture 1931

Pen and ink wash on paper

292 x 235 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Studies for Sculpture 1931

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Girl with Clasped Hands 1930

Cumberland alabaster

381 x 415 x 150 mm

British Council Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Girl with Clasped Hands 1930

British Council Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

There are no recorded statements by Moore specifically about Half-Figure and it is notable that despite having been selected for display in a number of high profile exhibitions, including Moore’s first retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1946, it has received very little critical attention to date. Between 1929 and 1932 Moore created at least seventeen half or three-quarter length female figures in different types of stone and concrete, including Girl with Clasped Hands 1930 (fig.4). Half-Figure has been considered in general discussions of these works, which, as the critic Will Grohmann notes, variously clasp their hands in front of them, or wrap their arms around their bodies.8 The squat, block-like composition of Girl with Clasped Hands serves to emphasise the graceful fluidity and elongated features of Half-Figure. In 1988 curator Susan Compton also commented on the stylistic shift that Half-Figure and Girl 1932 (Tate T00240) make evident: ‘After the almost fierce quality of those of 1929–30, Moore carved two half-length figures which have a surprising quality of near gentleness. He achieved the change by altering his approach to the head and hair, but he also rounded the shoulders to give a more feminine appearance’.9 For Compton, the feminine ‘gentleness’ of these two half-length sculptures is ‘surprising’ when compared to the bulkier earlier works, but she goes on to suggest that the sculptures ‘convey some of the awkwardness of girlhood’.10

Scholars agree that the impetus behind the production of Moore’s half-length female figures originated from Moore’s interest in primitivism and, in particular, ancient Sumerian sculpture.11 Primitivism is an over-arching term used by art historians to describe an early twentieth-century tendency within European art that sought to emulate the forms and perceived values of ancient non-Western art.12 The arts of so-called primitive cultures, which included tribal art from Africa, Asia and the Pacific Islands, as well as prehistoric, Byzantine and medieval European art, were deemed to be more immediate and powerful than the refined classicism of the European fine art tradition. Moore’s interest in primitivism dates from his time as a student at Leeds School of Art, where, in 1920, he read the art critic Roger Fry’s influential book Vision and Design (1920), which included chapters on African, Islamic and ancient American arts. As the art historian Christopher Green has suggested, for Fry and many others the turn to primitive art ‘offered a stimulus for rebuilding the broader terms of the European tradition’.13 In 1947 Moore recalled that ‘Fry opened the way to other books and to the realisation of the British Museum. That was the beginning really ... One room after another in the British Museum took my enthusiasm’.14 Indeed, throughout the 1920s Moore examined the formal characteristics and properties of primitive sculpture on display in the British Museum and by studying publications such as Herbert Kühn’s Die Kunst Der Primitiven (1923), which provided source material for a series of sketches made in 1926.15 In examining objects from tribal cultures in Africa, Asia, Native and South America, Moore identified sculptural precedents that not only demonstrated the dictum of direct carving, but that he believed conveyed strong and direct feelings through elemental shapes.16 In an interview given in 1932, the year Half-Figure was created, Moore discussed his admiration of the simplified forms of non-Western carvings, stating:

The primitive simplifies, I think, through directness of emotional aim to intensify their expression. Simplicity as an aim in itself tends to emptiness and monotony, but simplicity in carving, interpreted as lack of surface trimmings, reveals the contrast in section, axis, direction and bulk between different shapes and so intensifies the three-dimensional power in a work.17

Moore’s interest in the contrast between directional forces can be seen in Half-Figure, not only in the turn of the figure’s head, but also in the diagonal pull of the shoulders, which cuts across the vertical axis of the torso. Similarly the figure’s angled arms cross the vertical axis of the torso creating movement, directing the viewer to look across and around the sculpture as well as up and down it. In her 2005 publication Mother Stone: The Vitality of Modern British Sculpture, art historian Anne Wagner compared Moore’s arrangement of carefully balanced body parts in his half-figure sculptures to a ‘high-wire act’ in which Moore was able to combine solidity and instability. Wagner declared that Moore was not aiming for representational truth but for ‘a way of forming that will lend his work a sense of life, of aliveness; and for that mere bodily mimesis will not suffice’.18

Moore’s specific interest in the art of Sumeria, an ancient culture from Mesopotamia – a region corresponding to modern-day Iraq and parts of Syria, Turkey and Iran – can be understood in relation to his engagement with primitivism. In 1974 Moore recalled that ‘my first contact with Mesopotamian art occurred when I saw the works exhibited in the British Museum’.19 Between 1920 and 1930 Iraq had been a British mandate territory and during these years a number of British archaeological surveys had taken place. Archaeological artefacts, sculptures and objects found during these surveys were collected and exhibited in commercial and public galleries, including the British Museum and the Louvre in Paris, and as a consequence the ancient Babylonian, Assyrian, and Sumerian cultures found within Mesopotamia were widely discussed within artistic and academic circles. In addition to his research at the British Museum, Moore would also have had the opportunity to see and discuss Sumerian art with the commercial art dealer Sydney Burney, at whose gallery he exhibited in November 1932. Burney wrote an article on ancient Sumerian sculpture for the London Illustrated News in 1931 and regularly exhibited artworks from Sumeria in his gallery during the early 1930s. Also, Moore is likely to have known that his former life-drawing tutor and friend Leon Underwood spent much of 1931 restoring the ancient Sumerian sculpture of Gudea, Ruler of the City State of Lagash, which belonged to Burney prior to its sale to the British Museum in July that year.20

Statue of a female worshipper from Lagash, southern Iraq, c.2900 BC

Brown limestone

220 mm

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of The British Museum

Fig.5

Statue of a female worshipper from Lagash, southern Iraq, c.2900 BC

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of The British Museum

See the alabaster figure of a woman which is in the British Museum and reproduced here, with her tiny hands clasped in front of her. It is as though the head and the hands were the two equal focal points of the figure – one cannot look at the head without being conscious also of the held hands. But in almost all Sumerian work the hands have a sensitiveness and significance; even in the very earliest terracotta figures, where each hand seems no more than four scratches, there is a wealth of meaning there.22

Although the hands of Moore’s Half-Figure are not clasped, but wrap around the figure’s body, cupping the elbow and breast, they have nonetheless been sensitively carved, suggesting a delicate touch. There does not appear to be any overt physical pressure being applied to the skin by the hands, and yet when considered in relation to the facial expression, evokes an uncanny combination of tension and ease. In 1980 Moore reflected on the importance of hands, a motif to which he returned throughout his career, observing that:

Hands can convey so much – they can beg or refuse, take or give, be open or clenched, show content or anxiety. They can be young or old, beautiful or deformed ... throughout the history of sculpture and painting one can find that artists have shown through the hands the feelings they wished to represent.23

Although made towards the end of his life, Moore’s remarks about the emotional power of hands remain useful for interpreting Half-Figure.

Detail of Half-Figure 1932 showing hole between head and ponytail

Tate T00241

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Detail of Half-Figure 1932 showing hole between head and ponytail

Tate T00241

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In his 1937 essay ‘A Sculptor Speaks’ Moore linked his use of holes in sculpture to the holes found naturally in pebbles worn by the sea.24 In the summers of 1930 and 1931 Moore and a group of fellow artists, including Hepworth, holidayed together in Happisburgh on the coast of East Anglia. Examining flint and ironstone pebbles found on the beach, the artists began to think about the ways in which natural forces had shaped stone. Moore later explained, ‘the hole connects one side to another, making it immediately more three-dimensional. A hole can itself have as much shape-meaning as a solid mass’.25

Although Moore’s use of holes is generally associated with his interest in natural forms, they may also have been prompted by his study of ancient primitive sculpture. Moore had studied examples of Mayan and Aztec carving closely during the late 1920s, supplementing his visits to the British Museum by reading various publications on ancient Mexican art. The gap found between the figure’s neck and ponytail in Half-Figure may have been prompted by an illustration of an ancient Mexican sculpture (fig.7) in Ernst Fuhrmann’s publication Mexiko III (1922), which Moore bought in 1923. The image shows a side-view of a sculpture of a seated man which has a similar gap between the neck and the hair (or head-dress).

Statue of Tetisheri Enthroned c.1890 BC (originally dated c.1575 BC)

Limestone

360 x 135 x 245 mm

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.8

Statue of Tetisheri Enthroned c.1890 BC (originally dated c.1575 BC)

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

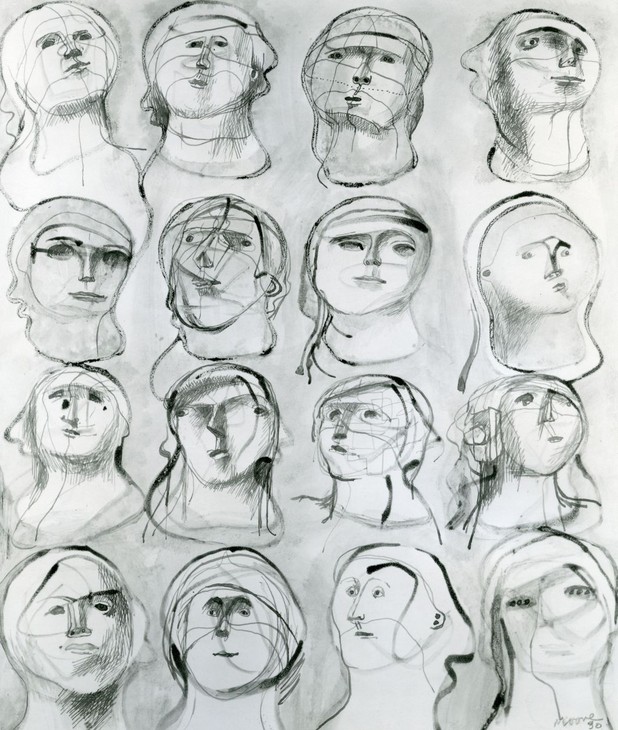

Henry Moore

Sixteen Heads 1932

Graphite, chalk, wash, pen and ink

381 x 317 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Sixteen Heads 1932

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

This facial schema is also reminiscent of faces found in early Italian Renaissance paintings such as those by Giotto and Piero della Francesca. Moore had travelled to Italy for the first time in February 1925, having been awarded a travelling scholarship from the Royal College of Art (RCA) upon his graduation in 1924. He had initially been very reluctant to travel to Italy, and had wanted to use the scholarship to study in Paris, but the terms of the scholarship were set and Moore visited Genoa, Pisa, Rome and Florence during his trip. The curator and art historian Penelope Curtis has acknowledged that ‘the idea that Italy influenced Moore at all in the years following his return is not a standard reading’ of his work.30 However, in a letter dated 12 March 1925 to William Rothenstein, Principal of the RCA, Moore wrote ‘Giotto has made the greatest impression on me (perhaps partly because he’s the most English of the primitives)’.31

It is likely that Moore unconsciously absorbed the examples of the so-called ‘primitive’ quattrocento painters. In his book Piero della Francesca (1951) the art historian Kenneth Clark described Piero as follows: ‘He is not a romantic. His faces, though they sometimes suggest great depth, are devoid of sentiment. He thinks in mass rather than in line, is sparing in detail, and never indulges in rich texture for its own sake’.32 Clark could equally have been discussing Moore’s sculptures when writing these words and it is notable that Clark dedicated Piero della Francesca to Moore. Later in 1957 Moore spoke of his admiration for the way in which Piero married an outward calm with a disturbed, primitive element.33

It is clear that with Half-Figure Moore was not attempting to emulate one single example of primitive art or follow one single artistic convention. Given the geographical range and stylistic diversity of Moore’s artistic referents he most likely amalgamated – consciously or not – the features of several different primitive, historical and contemporary examples in his own sculpture, rather than attempt to emulate one particular object or style.

Half-Figure was bought by E.C. Gregory (1888–1959) from Moore’s exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in November 1933. Known as Peter to his friends, Eric Craven Gregory was an early supporter of Moore’s work, and remained a friend and patron throughout his life. He was a regular visitor to Moore’s home and accompanied Moore on his first trip to the United States in 1946. Gregory only bought works by living artists, believing that it was important to support art of the moment rather than create collections of the past.34 In order to ensure that his collection remained ‘alive’ he regularly loaned works for exhibition, and in 1946 loaned Half-Figure for Moore’s exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Although it was not included in Moore’s exhibition of drawings at the Phillips Memorial Gallery in Washington D.C. in May 1946, the sculpture was used on the show’s promotional posters, perhaps standing as a representative example of Moore’s sculptural work. At the time of Gregory’s death in 1959 his art collection numbered over 150 items and included paintings by Gillian Ayres, Sandra Blow, Alan Davie, Terry Frost and William Scott.

Half-Figure remained in Gregory’s possession until his sudden death in February 1959, aged seventy-one. Among the numerous tributes published shortly after his death was an obituary by Moore published in the Times:

I should like to add my personal tribute to the memory of my good friend Peter Gregory ... When first I knew him, I was an unknown sculptor. At that time there were very few, less than half a dozen collectors of modern sculpture in this country ... The debt that I owe him is enormous. It is thanks to Peter Gregory and a very few others of his sort that young sculptors in this country can nowadays anticipate that their work may be of interest to their compatriots ... He was always open to new ideas and directions. His heart remained young, and he was at all times ready to help those whose work he admired or who he felt needed the various forms of help that he could give. He gave his help quietly, unobtrusively, and for the right reasons.35

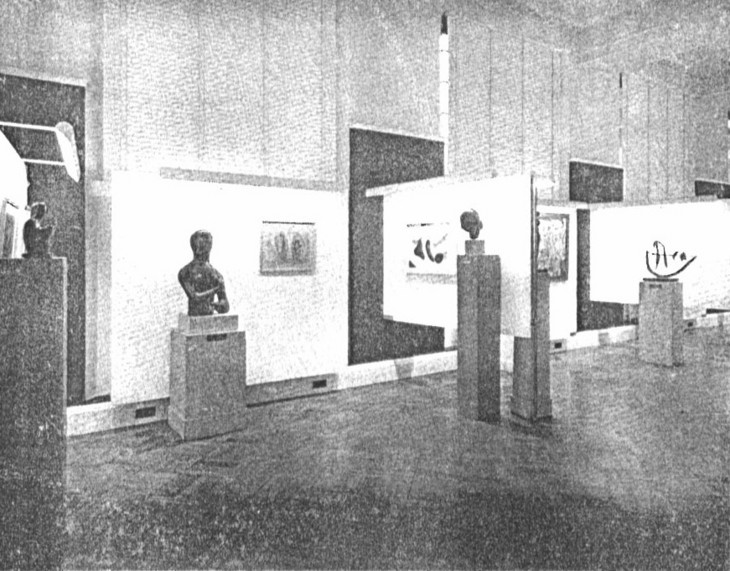

Photograph of Half-Figure 1932 and Figure 1931 on display at the Tate Gallery c.1959–60

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Photograph of Half-Figure 1932 and Figure 1931 on display at the Tate Gallery c.1959–60

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In 1959 the Tate Gallery’s ground floor exhibition spaces were redesigned.37 Improvements included the construction of screens which projected outwards into the galleries to create small bays, and the introduction of humidity and temperature control systems. The newly acquired Half-Figure was included in one of the re-hung galleries alongside Moore’s other sculpture from the Gregory Bequest, Figure 1931 (fig.10).

Alice Correia

January 2013

Notes

Henry Moore, ‘Statement for Unit One’ in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, pp.29–30, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.191.

Herbert Read, ‘A Nest of Gentle Artists’, Apollo, September 1962, pp.536–40. For discussion on the interactions of this group of artists see also Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson in the 1930s: A Nest of Gentle Artists, exhibition catalogue, Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, Norwich 2009.

John Skeaping, Half-Length Figure of a Woman, c.1929–30 (location unknown), reproduced in John Skeaping 1901–1980: A Retrospective, exhibition catalogue, Arthur Ackermann & Son, London 1991, p.10.

Susan Compton, ‘Catalogue’, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, p.178.

See Charles Harrison, English Art and Modernism, 1981, revised edn, New Haven and London 1994, p.229; Sophie Bowness, ‘Modernist Stone Carving in England and “The Big View of Sculpture”’ in Carving Mountains: Modern Stone Sculpture in England 1907–37, exhibition catalogue, Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge 1998, p.35; Jon Wood, ‘Gods, Graves and Sculptors: Gudea, Sumerian Sculpture and the Avant-Garde, c.1930–1935’, Sculpture Journal, no.10, 2003, pp.67–82.

Christopher Green, ‘Expanding the Canon: Roger Fry’s Evaluations of the “Civilized” and the “Savage”’, in Christopher Green (ed.), Art Made Modern: Roger Fry's Vision of Art, exhibition catalogue, Courtauld Institute Galleries, London 1999, p.126.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeney, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, p.182, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.44.

See Henry Moore, ‘Primitive Art’, Listener, 24 April 1941, pp.598–9, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, pp.102–6.

Henry Moore, ‘On Carving’, New English Weekly, 5 May 1932, pp.65–6, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.190.

Anne Wagner, Mother Stone: The Vitality of Modern British Sculpture, New Haven and London 2005, p.20.

Henry Moore, ‘Mesopotamian Art’, foreword to Lucienne Laroche, The Middle East, London 1974, pp.7–8, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.109.

Henry Moore, ‘Mesopotamian Art’, Listener, 5 June 1935, pp.944–6, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.101.

Henry Moore, The Artist’s Hand, Much Hadham 1980, cited in Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011, p.66.

Henry Moore, ‘A Sculptor Speaks’, Listener, 19 August 1937, pp.338–40, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.195.

In 1984 scholarship endorsed by the British Museum argued that this Egyptian statuette of Queen Tetisheri was a forgery, probably made shortly before 1890 for the European market for antiquities. However, this information does not diminish the importance Moore placed on this work. See http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=120863&partId=1&searchText=Limestone%20statue%20of%20Tetisheri%20enthroned , accessed 10 January 2013.

Penelope Curtis, ‘British Modernist Sculptors and Italy’, British Artists in Italy 1920–1980, exhibition catalogue, Canterbury College of Art, Canterbury 1985, p.13.

Henry Moore, ‘The Hidden Struggle’, Observer, 24 November 1957, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, pp.118–19.

Related essays

- Henry Moore and Direct Carving: Technique, Concept, Context Sarah Victoria Turner

- Henry Moore and World Sculpture Dawn Ades

- Henry Moore and Stone: Methods and Materials Sebastiano Barassi and James Copper

Related material

Related reviews and articles

- Henry Moore, ‘Obituary: Mr E.C. Gregory’ Times, 19 February 1959, p.12.

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Half-Figure 1932 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, January 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www