Henry Moore OM, CH Girl 1931

Image 1 of 15

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Girl

1931

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

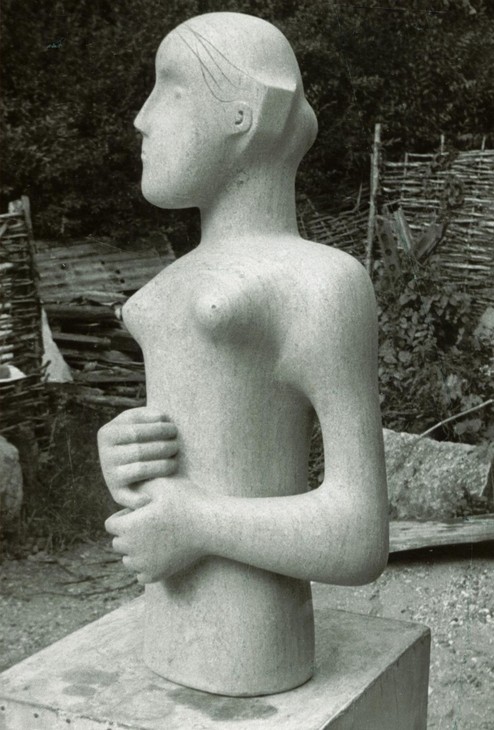

This sculpture of an adolescent girl is one in a series of half-length female figures carved by Henry Moore between 1929 and 1932. The linking of the figure’s hands and their central position reveal Moore’s interest in ancient Mesopotamian sculpture during this period.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Girl

1931

Ancaster stone with limestone base

737 x 368 x 273 mm

Purchased 1952 with assistance of the Knapping Fund

N06078

Girl

1931

Ancaster stone with limestone base

737 x 368 x 273 mm

Purchased 1952 with assistance of the Knapping Fund

N06078

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist through the 7 & 5 Society by Clive Branson, London, February 1932; presented by Branson to the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, May 1932; bought from Whitechapel Art Gallery by Tate Gallery, London, July 1952.

Exhibition history

1932

Eleventh Exhibition of the 7 & 5 Society, Leicester Galleries, London, February 1932, no.62.

1948

Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, British Pavilion, Venice Biennale, Venice, June–September 1948, no.13.

1949

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1923–1948, Wakefield City Art Gallery, Wakefield, April–May 1949; Manchester City Art Gallery, Manchester, June–July 1949, no.22.

1949

Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, October 1949; Musée d’art moderne, Paris, December 1949; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, January 1950; Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, March 1950; Städtische Kunstsammlungen, Düsseldorf, May 1950; Kunsthalle Berne, Berne, June–July 1950, no.16.

1951

Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, May–July 1951, no.66.

1968

Henry Moore, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, May–July 1968; Museum Boymans-Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, September–November 1968, no.20.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978.

1981

British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century. Part One: Image and Form 1901–50, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, September–November 1981, no.113.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, Palacio de Velázquez, Palacio de Cristal, Parque de El Retiro, Madrid, May–August 1981, no.53.

1982

Henry Moore: Head-Helmet, DLI Museum and Arts Centre, Durham, June–July 1982, no.11.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983.

1988

Henry Moore, Royal Academy of Arts, London, September–December 1988, no.17.

2001–2

Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, February–May 2001; Legion of Honor, San Francisco, June–September 2001; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., October–January 2002, no.18.

2002

Henry Moore: Rétrospective, Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul, July–November 2002, no.32.

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, May–September 2004, no.84.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.14.

2010–11

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, October 2010–February 2011; Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, March–June 2011, no.27.

2012–13

The Perfect Place to Grow: 175 Years of the Royal College of Art, Royal College of Art, London, November 2012–January 2013.

References

1932

R.H. Wilenski, The Meaning of Modern Sculpture, London 1932, p.164, reproduced pl.10.

1933

Anon, ‘Girl; Carving in Ancaster Stone by Henry Moore’, Heaton Review: A Northern Miscellany of Art and Literature, vol.6, 1933, reproduced p.17.

1944

Herbert Read (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, London 1944, reproduced pl.29a.

1948

David Sylvester, ‘The Evolution of Henry Moore’s Sculpture: I’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, June 1948, p.159.

1948

Guilio Carlo Argan, Henry Moore, Turin 1948, reproduced pl.4.

1951

David Sylvester (ed.), Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1951, p.11.

1954

F.M. Godfrey, ‘Recent additions to the Tate Gallery’, John O’London’s Weekly, 5 March 1954 (Henry Moore Foundation Archive).

1957

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, London 1957, p.8, no.109, reproduced p.64.

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, p.29, reproduced pls.8–9.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.30–4.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.15.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, exhibition catalogue, Palacio de Velázquez, Madrid 1981, reproduced p.48.

1982

Henry Moore: Head-Helmet, exhibition catalogue, DLI Museum and Arts Centre, Durham 1982, reproduced p.15.

1983

William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983, reproduced p.28.

1988

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, p.178, reproduced.

1992

David Mitchinson and Julian Stallabrass, Henry Moore, London 1992, reproduced p.43.

2001

Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001, reproduced p.95.

2002

Henry Moore: Rétrospective, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul 2002, reproduced p.67.

2003

Jon Wood, ‘Gods, Graves and Sculptors: Gudea, Sumerian Sculpture and the Avant-Garde, c.1930–1935’, Sculpture Journal, no.10, 2003, p.67–83, reproduced p.78.

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2004, reproduced p.149.

2005

Henry Moore y México, exhibition catalogue, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City 2005, reproduced p.44.

2005

Anne Middleton Wagner, Mother Stone: The Vitality of Modern British Sculpture, New Haven and London 2005, pp.20–3, reproduced pp.20–1.

2010

Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, reproduced p.113.

Technique and condition

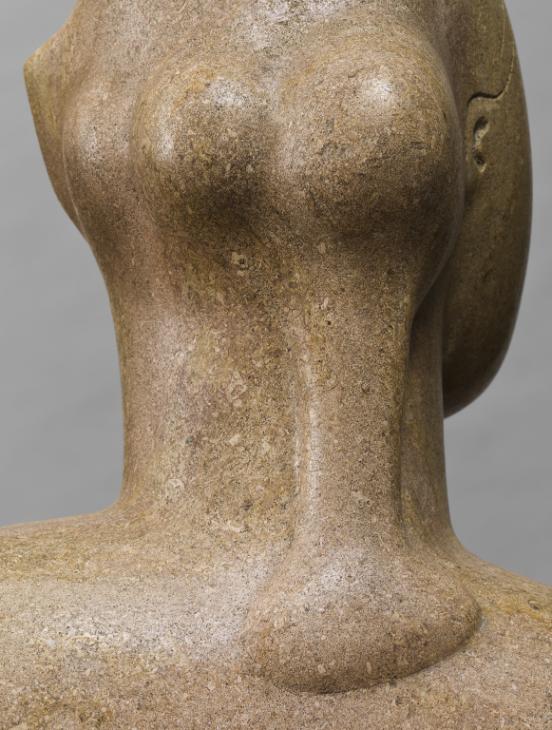

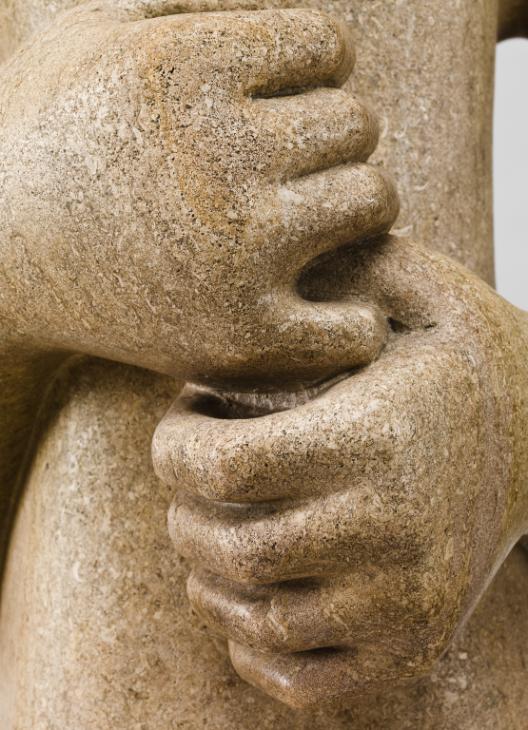

Girl is a sculpture of the torso of a naked girl carved from pink and yellow coloured Ancaster stone, mounted on a cuboid rectangular limestone base. Moore carved the sculpture from a single block of this Lincolnshire limestone by roughing out the form using a hammer and chisels before working with progressively smaller chisel sizes to carve the finer details. Further shaping was then carried out using a range of files before the sculpture was sanded and polished to a smooth finish.

Detail of Girl 1931 showing chisel marks on hands

Tate N06078

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of Girl 1931 showing chisel marks on hands

Tate N06078

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of Girl 1931 showing incised lines and pigmented wax

Tate N06078

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of Girl 1931 showing incised lines and pigmented wax

Tate N06078

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Although very few tool marks are visible there are some small chisel and file marks on the hands (fig.1). Details such as the eyes, hair, nipples, and nostrils are picked out with drilled holes and incised lines (fig.2). Close examination here reveals that Moore has used a dark material, perhaps a pigmented wax, to accentuate these features. There are pale inclusions on the surface of the sculpture that are characteristic of this type of stone and are the result of fossilised fragments of shell. Some small restorations are visible on the figure’s back and also on the figure’s right side.

The sculpture sits flat on its base where residues of an adhesive used to fix the sculpture can be seen, along with a buff coloured cement that was used as a filler for the join. There is a small chamfer around the lower edge of the torso where it meets the base, similar to that seen on Moore’s Half-Figure 1932 (Tate T00241). There is no inscription visible.

Lyndsey Morgan

October 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', October 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Girl 1931 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2012, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Girl is a stone sculpture of a naked adolescent girl shown from her head to her hips, fixed on top of a cuboid plinth made from limestone. Her head is oval, with a prominent jutting chin. The nose has been carved in the shape of a tetrahedron, with the bridge tapering upwards and curving around either side of the face to delineate the eye brows. Circular nostrils have been drilled into the lower part of the nose. The eyes are slightly convex areas of stone that have been incised with two circles outlining the area of the iris and two drilled circles denote the pupils. The mouth is small and the lips appear to be pursed together, with the upper lip forming a stark ‘m’ shape, while the lower lip is straight. The eyes, nose and mouth appear small in comparison to the size of the head and are concentrated in the middle of the face.

Moore accentuated the incised or drilled details including the eyes and nostrils by adding a dark material, possibly a pigmented wax, or by rubbing a burnt match over these areas. These incisions appeared much more prominent in early black and white photographs of the sculpture. Strands of hair are denoted by incised lines which also indicate the girl’s hairline. One of the strands of hair also forms the outline of the right ear for which a ‘c’ shaped hollow denotes the ear canal. These rounded shapes are echoed in a series of three globular shapes suggesting buns of hair. A skein of hair has been carved in relief and runs down the girl’s neck. When seen from her left side a rectangular shape projects from the side of her skull. It is unclear what this shape is meant to denote.

The torso is an elongated tubular column, which leans slightly to the right and tapers in slightly just above the hips. The breast bone curves forwards from the thick neck, and the breasts are presented as two small domes positioned lopsidedly on the girl’s otherwise flat chest. Nipples have been denoted by two small drilled indentations. She has broad shoulders that exceed the width of her hips, making the sculpture appear top heavy; seen from the front the shoulders are presented on a diagonal with the proper left shoulder raised slightly, while the right is lower. The sculpture’s muscular shoulders lead to thinner upper arms. Although carved from a single block of limestone, a gap between the upper arms and the torso has been carved while the forearms and hands are attached to the main body. The hands are positioned in front of the girl’s belly and are loosely clenched, with the thumb of her left hand hooked between the small and ring fingers of the right hand (fig.1).

The sculpture is carved from Ancaster stone, a limestone found around the village of Ancaster in Lincolnshire. Because of its sedimentary composition Ancaster stone does not have a uniform colour. In Girl, bands of pink can be seen running through the mainly yellowish stone, especially on the left shoulder. Close examination of the surface reveals pale flecks caused by the presence of fossilised shell embedded in the stone. Ancaster stone is typically used as a building material, and was notably used in the construction of Norwich Cathedral in the eleventh century. In a review in the Sheffield Independent of Moore’s solo exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in London in 1931, the year Girl was created, an unnamed critic noted Moore’s use of unusual materials for carving, remarking that ‘his show is full of experimental sculptures in English building stones, some of which have never been used for this purpose before’.1 Although Girl was not included in this exhibition, this commentary indicates that Moore’s use of English stones, and those more commonly used for buildings, was not unusual at this stage in the artist’s career. In 1978 Moore accounted for his use of English stones, stating: ‘in the early part of my career I made a point of using native materials because I thought that, being English, I should understand our stones. They were cheaper, and I could go round to a stonemason and buy random pieces. I tried to use English stones that hadn’t been used before for sculpture.’2

Photograph of Girl 1931 in an outside location

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Photograph of Girl 1931 in an outside location

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore created Girl using the method of direct carving. This meant that Moore worked directly on the stone using a range of chisels, rifflers and hammers, without the aid of preparatory sketches or maquettes (scale models made in clay or plaster). Moore and his contemporaries, including Barbara Hepworth and John Skeaping, believed that when carving directly into stone or wood to create a unique artwork, the form or shape of the final sculpture should evolve through the processes of its making as the artist responded to the texture, graining and colour of the material under hand. In his essay ‘A View of Sculpture’ published in 1930, Moore argued that it was important for the artist to ‘think and create in his material by direct carving, understanding and being in sympathy with his material so that he does not force it beyond its natural constructive build, producing weakness’.5 He went on to state that ‘sculpture in stone should look honestly like stone [and] that to make it look like flesh and blood, hair and dimples is coming down to the level of the stage conjuror’.6 This is perhaps why in Girl Moore seems to have harnessed the grain of the limestone, which runs vertically through the sculpture, in order to emphasise its elongated height.

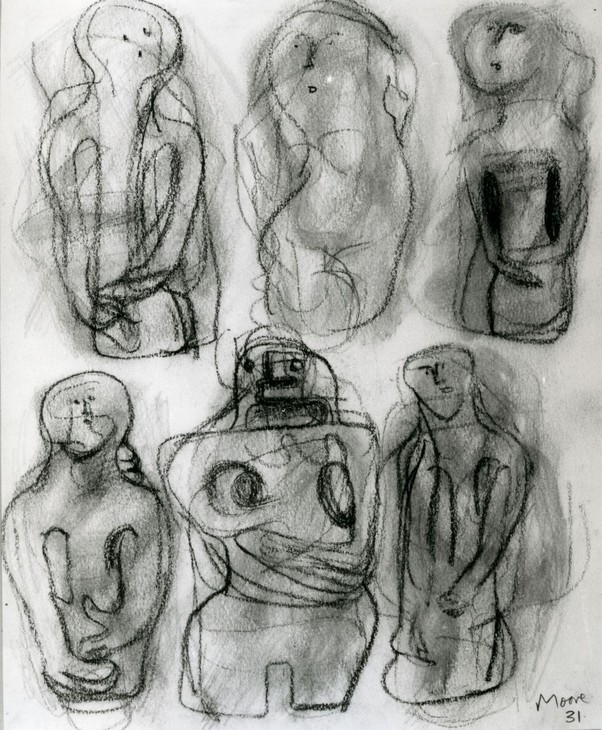

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture: Six Half-Figures 1931

Pastel on paper

308 x 250 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture: Six Half-Figures 1931

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

However, it should be noted that this subject and pose was not unique to Moore at this time and can also be seen in contemporaneous works such as Hepworth’s Figure of a Woman 1929–30 (Tate T00952). In Hampstead, Moore belonged to what the critic Herbert Read described as ‘a nest of gentle artists’, which included Hepworth and Skeaping.7 Moore’s artistic circle had mutual interests and similar approaches to carving during the late 1920s and early 1930s, and these commonalities resulted in works with similar compositional forms.

Henry Moore

Half Figure No.1 1929

Cast concrete

425 x 255 x 185 mm

British Council Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Half Figure No.1 1929

British Council Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Girl with Clasped Hands 1930

Cumberland alabaster

381 x 415 x 150 mm

British Council Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Girl with Clasped Hands 1930

British Council Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

It is notable that despite having been selected for a number of high profile exhibitions, including the Venice Biennale in 1948 and Moore’s solo exhibition at the Tate Gallery in 1951, Girl has not been the subject of individual critical attention to date. In 1960 the art historian Will Grohmann considered the work in relation to the series of female half-figure sculptures Moore made between 1929 and 1932.8 For example, Girl and the earlier Half Figure No.1 (fig.4) have both been cut just below the waist so that the torso sits directly on a base. The arms and hands are held in front of each figure, and in both examples the fingers of opposite hands are touching or gripping each other. However, it is notable that while not entirely naturalistic, Girl does appear to be less schematic than the earlier work. The truncated torso of Half Figure No.1 contrasts with the elongated body and neck of Girl, while the empty cavity in the belly of Half Figure No.1 does not correspond with the later work. Close examination reveals that the hands of the two sculptures are also markedly different. In the earlier Half Figure No.1 the fingers have not been individually carved and are identified by simple rectangular outlines while the hands themselves are more akin to paddles. Although this form of presentation may be explained by the difficulty of casting concrete, Moore repeated this type of hand in other stone works such as Girl with Clasped Hands 1930 (fig.5) made from Cumberland alabaster. In Girl with Clasped Hands, rather than carving individual digits on the hands Moore merely suggested the presence of fingers with lightly scored lines on the stone’s surface. However this sculpture is closer to Girl in that the stone has been pierced in order to separate the arms from the torso. Seen together, the squat, block-like composition of Half Figure No.1 and Girl with Clasped Hands also serves to emphasise the way in which the torso of Girl has been lengthened, distinguishing the later sculpture from earlier works of the same subject. In 1988 the curator Susan Compton also commented on the stylistic shift that Girl and Half-Figure 1932 (Tate T00241) make evident: ‘After the almost fierce quality of those [half-figure sculptures] of 1929–30, Moore carved two half-length figures which have a surprising quality of near gentleness. He achieved the change by altering his approach to the head and hair, but he also rounded the shoulders to give a more feminine appearance’.9 For Compton, the feminine ‘gentleness’ of these two half-length sculptures is ‘surprising’ when compared to the bulkier earlier works, but she goes on to suggest that Girl is ‘thoroughly original and the long hair and pubescent breasts convey some of the awkwardness of girlhood’.10

The first critic to comment on Girl was R.H. Wilenski in his 1932 publication The Meaning of Modern Sculpture. Like Moore’s essay of 1930, Wilenski prioritised direct carving as a method for creating sculptures with universal meaning. In a chapter titled ‘The Modern Sculptors’ Creed (i)’ Wilenski noted that ‘When the modern sculptors speak of carving they thus mean direct carving by the sculptor himself; and they regard direct carving as a kind of collaboration between the sculptor and the substance’.11 Wilenski discussed Moore’s work, specifically his recent half-figures and ‘mother and child’ sculptures, identifying an affinity between the forms of the sculptures and the materials in which they were made. He also suggested that Moore’s ‘concept of truth in sculpture is the organisation of stone-form as a symbol of life’.12 In stripping away the exactitudes of anatomy and avoiding ‘the particular shapes of some particular woman’ Wilenski argued that Moore sought to present his subject matter in universally recognisable shapes and in doing so aligned himself with the ancient and ‘primitive’ carvers, whose work they both admired.13

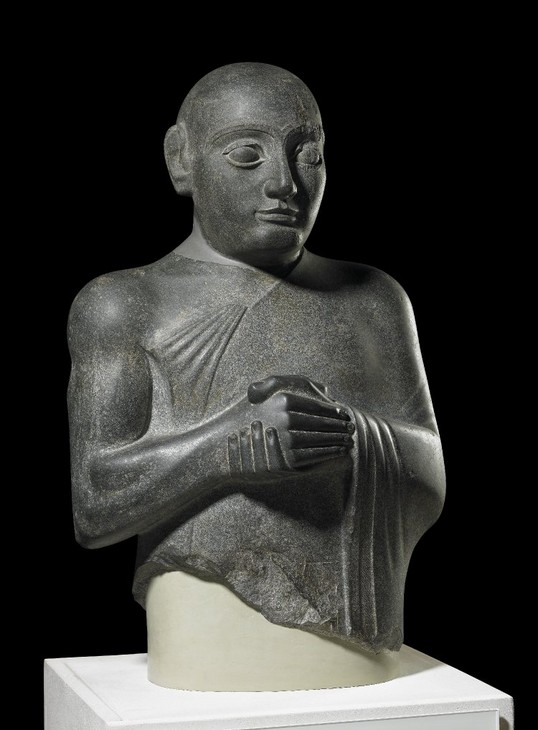

Wilenski argued that Moore’s carvings were attempts ‘to express the kind of formal meaning which the sculptor had experienced in Sumerian sculpture’ and made a comparison between an ancient Sumerian sculpture of Gudea, Ruler of the City State of Lagash c.2125–2025 BC (fig.6), which Moore would have known in the British Museum, and Moore’s Mother and Child 1931.14 Wilenski admired the sculpture of Gudea for the way the ancient carver used a sphere, rectangle and cube to represent the head, body and hands. Wilenski identified that ‘the modern sculptors have lost faith in the nineteenth century attitude’ towards art and identified contemporary sculptors, including Moore, who were reviving sculpture through recourse to so-called primitive, non-Western art forms.15

Primitivism is an over-arching term used by art historians to describe an early twentieth-century preference within European art that sought to emulate the forms and perceived values of non-Western art. The arts of so-called primitive cultures, which included tribal art from Africa, Asia and the Pacific Islands, as well as prehistoric and medieval European art, were deemed to be more authentic than the refined classicism of the European fine art tradition. Moore’s interest in ancient non-Western art dates from his time as a student at Leeds School of Art, where, in 1920, he read the art critic Roger Fry’s influential book Vision and Design (1920), which included chapters on African, Islamic and ancient American arts. As the art historian Christopher Green has suggested, for Fry and many others, the turn to primitive art ‘offered a stimulus for rebuilding the broader terms of the European tradition’.16 In 1947 Moore recalled that ‘Fry opened the way to other books and to the realisation of the British Museum. That was the beginning really ... One room after another in the British Museum took my enthusiasm. The Royal College of Art meant nothing in comparison’.17

Throughout the 1920s Moore had explored the formal characteristics and properties of ancient non-Western sculpture housed in the British Museum in London. He also studied recent publications such as Herbert Kühn’s Die Kunst Der Primitiven (1923), which provided source material for a series of sketches made in 1926.18 In his foreword to the exhibition Primitive African Sculpture held at the Lefevre Galleries, London in 1933, Moore wrote:

Negro Sculpture played a great part in the birth of cubism, and has had a powerful influence on all contemporary painting and sculpture. It has helped the artist to realise the intrinsic emotional significance of shapes as distinct from their representational values, and has freed him to recognise again the importance of the material in which he works.19

Similarly, in an interview given in 1932, the year after Girl was created, Moore discussed his admiration towards the simplified forms of non-Western carvings, stating:

The primitive simplifies, I think, through directness of emotional aim to intensify their expression. Simplicity as an aim in itself tends to emptiness and monotony, but simplicity in carving, interpreted as lack of surface trimmings, reveals the contrast in section, axis, direction and bulk between different shapes and so intensifies the three-dimensional power in a work.20

Moore’s interest in the contrast between directional forces can be seen in the diagonal pull of the shoulders of Girl, which cuts across the vertical axis of the torso. Similarly the bulkiness of the shoulders contrasts with the much thinner, elongated belly. In her 2005 publication Mother Stone: The Vitality of Modern British Sculpture, art historian Anne Wagner compared the arrangement of carefully balanced body parts in Girl to a ‘high-wire act’ in which Moore was able to combine constancy and instability. Wagner declared that Moore was not aiming for representational truth but for ‘a way of forming that will lend his work a sense of life, of aliveness; and for that mere bodily mimesis will not suffice’.21

Following Wilenski’s discussion of Moore’s sculpture, scholars have agreed that it was ancient Sumerian sculpture that provided the impetus for Moore’s sculptures of half-figures with folded or clasped hands in the late 1920s and early 1930s.22 It is within this context that Girl is usually discussed. Sumeria was an ancient culture in Mesopotamia, a region corresponding to modern-day Iraq and parts of Syria, Turkey and Iran. Between 1920 and 1930 Iraq had been a British mandate territory and during these years a number of British archaeological surveys took place. Archaelogical artefacts, sculptures and objects found during these surveys were collected and exhibited in public galleries, including the British Museum and the Louvre in Paris, and as a consequence, the ancient Babylonian, Assyrian, and Sumerian cultures found within Mesopotamia were widely discussed within artistic and academic circles. In 1974 Moore wrote that he first came in contact with Mesopotamian art at the British Museum, whose holdings of art from the region expanded during the early 1930s.23 However, Moore would also have had the opportunity to see and discuss Sumerian art with the gallerist Sydney Burney, with whom Moore exhibited in November 1932. Burney wrote an article on ancient Sumerian sculpture for the London Illustrated News in 1931 and regularly exhibited artworks from Sumeria in his gallery. Given his continued friendship with his former life-drawing tutor Leon Underwood, Moore may also have been aware that Underwood spent much of 1931 restoring the Sumerian figurative sculpture of Gudea, Ruler of the City State of Lagash, which belonged to Burney, prior to its sale to the British Museum in July that year.24

Gudea, Ruler of the City State of Lagash 2125–2025 BC

Black diorite

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of The British Museum

Fig.6

Gudea, Ruler of the City State of Lagash 2125–2025 BC

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of The British Museum

Statue of a female worshipper from Lagash, southern Iraq, c.2900 BC

Brown limestone

220 mm

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of The British Museum

Fig.7

Statue of a female worshipper from Lagash, southern Iraq, c.2900 BC

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of The British Museum

See the alabaster figure of a woman which is in the British Museum and reproduced here, with her tiny hands clasped in front of her. It is as though the head and the hands were the two equal focal points of the figure – one cannot look at the head without being conscious also of the held hands. But in almost all Sumerian work the hands have a sensitiveness and significance; even in the very earliest terracotta figures, where each hand seems no more than four scratches, there is a wealth of meaning there.28

The hands of Girl have not just been sensitively carved but suggest a sensitivity of touch. The fingers are gently interlocked and do not appear to apply any pressure to the skin. Yet the arrangement of the hands, when considered in relation to the facial expression, evokes an uncanny combination of tension and ease. In 1980 Moore reflected on the importance of hands, a motif to which he returned throughout his career, observing that:

Hands can convey so much – they can beg or refuse, take or give, be open or clenched, show content or anxiety. They can be young or old, beautiful or deformed ... throughout the history of sculpture and painting one can find that artists have shown through the hands the feelings they wished to represent.29

Although made towards the end of his life, Moore’s observation about the emotional power of hands remains useful for interpreting Girl.

In his 1935 essay Moore also praised the ‘full three-dimensional existence’ of Sumerian free-standing sculpture.30 For Moore, the ancient Sumerian carvers recognised the different sculptural requirements of works carved in relief or in the round. He argued that while relief carving required action and movement, free-standing sculpture is ‘still and static’, principally because of its physical mass.31 Although this quality of stillness is not exclusive to Sumerian sculpture, and may be found in other examples of non-Western art that Moore was examining at this time, such as Cycladic sculpture, it is the combination of stillness and solidity that may link Moore’s Sumerian examples to Girl.

In his 1948 summary of Moore’s career, the art critic David Sylvester broadly characterised Moore’s sculptures from 1930–2 as ‘humanist’.32 Although Sylvester did not define what he meant by this term, he suggested that Moore’s half-figures were successful because of their inherent emotional qualities which were universally accessible, and which could be understood and appreciated by people regardless of cultural background or age. Suggesting that Moore’s subject matter was in fact human emotion, Sylvester concluded that:

Humanism took him to the expression of character – a unique accomplishment among modern sculptors of comparable formal astringency. The reticence of expression which follows from that astringency is all the more telling than the over-emphasis of a Rodin: it implies passion never melodramatic, tenderness never cloying, sexuality never lascivious.33

For while the unadorned simplicity of Moore’s sculpture could be characterised as austere or even severe, Sylvester suggested that it was actually because of that astringency that Moore was able to convey emotion in its purest form without succumbing to clichéd or theatrical modes of expression. For Sylvester, Moore was able to achieve this through the depiction of ‘essentially commonplace’ subjects, ‘the mother tenderly suckling her child, or fearfully protecting it from a menacing external world, or holding it up as an offering to the sun; or, again, the freshness and virginal simplicity of a series of sculptures called Girl’.34

In February 1932 Girl was exhibited in the Eleventh Exhibition of the 7 & 5 Society, held at the Leicester Galleries, London. The sculpture was exhibited under the title Half-figure of a Girl and was purchased from the show by the painter and left-wing activist Clive Branson (1907–1944). Three months later Branson wrote to the Whitechapel Art Gallery, asking them to accept Girl as a donation, in addition to another sculpture by Maurice Lambert, Father and Son 1931 (Leeds City Art Gallery). In his letter to the gallery Branson stipulated that both he and his wife wished the donation to be ‘entirely anonymous’.35 Although the Whitechapel Gallery did not have a permanent collection of any kind, the work was accepted. This was not Branson’s only donation: in May 1933 he offered to present a large collection of works to the Tate, including two further sculptures by Henry Moore, four oil paintings by William Coldstream and a watercolour by Frances Hodgkins, among other artworks. This offer was rejected by Tate’s director J.B. Manson and the Board of Trustees.36

During the 1930s Clive Branson was a leading figure in the Artists International Association (AIA), an exhibiting society founded in 1933. Its initial objective was to mobilise ‘the international unity of artists against Imperialist War on the Soviet Union, Fascism and Colonial oppression’ and by 1936 had over 600 members.37 Branson, who was born to a wealthy family in 1907, met his wife Noreen Browne (granddaughter of the Eighth Marquess of Sligo, who became editor of the Labour Party’s Research Department magazine) at a charity concert in London’s East End in 1931. During the concert they discussed their mutual disgust at their wealth in the face of others’ deprivation. United by their shared ideology, they were married by June. Together, Branson and Browne left the affluent area of Chelsea and moved to Battersea where they dedicated their respective private incomes to assisting those in the area who were afflicted by poverty. It was the couple’s vehement desire to disassociate themselves from affluence that led Branson to donate his private art collection to institutions including Tate and the Whitechapel.

Branson joined the Communist Party in 1933 and took a leading role in the stand against Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists in Battersea. Five of Branson’s paintings depicting everyday working class life in Battersea are now held in the Tate collection, and one, Selling the 'Daily Worker' Outside Projectile Engineering Works 1937 (Tate T11788) depicts a man and woman selling copies of a communist newspaper outside a munitions factory.38 When the war against fascism in Spain broke out he quickly joined up to the British Battalion of the International Brigade. He was captured in almost his first battle, and spent eight months interned in one of General Franco’s concentration camps. Clive Branson was killed in action in Burma in 1942.

By June 1952 the Whitechapel Art Gallery was in considerable debt. The gallery’s director Bryan Robertson contacted John Rothenstein, who had replaced Manson as director of the Tate Gallery in 1938, to propose that Tate purchase Moore’s Girl for £500.39 Rothenstein put this proposal to the Tate Trustees, suggesting that funds might be available from the funding body of the Chantrey Bequest. The Chantrey Bequest is a charitable trust fund established in 1877 under the terms of the will of Sir Francis Chantrey, RA (1781–1841) and administered by the Royal Academy of Arts. The sculpture was seen by three Royal Academicians on the Bequest’s recommending committee: Maurice Lambert, James Woodford and Siegfried Charoux. Their feedback was largely negative: Lambert was concerned by the sculpture’s ‘lack of realism’,40 while Woodford described it as ‘a formless and degenerate piece of carving’.41 Disregarding this criticism, Tate decided to purchase the sculpture in September of that year, using resources from the Knapping Fund instead.

Since its entry into the Tate collection Girl has been on regular display. In 2010 Tate’s sculpture conservators cleaned the sculpture, removing surface dirt and revealing the stone’s fine variations of colour. The stone base was also treated; previous attempts at restoring damage had discoloured and plaster used to fill in chips was removed. The exposed repairs were then reworked and painted to blend with the natural colour of the stone.

Alice Correia

December 2012

Notes

Although Moore resigned from his post at the Royal College of Art in January 1931 there is some uncertainty whether he worked until the end of his contract at the end of the summer term. See Berthoud 2003, p.112.

Henry Moore, ‘A View on Sculpture’, Architectural Association Journal, May 1930, p.408, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, London 2002, p.187.

Christopher Green, ‘Expanding the Canon: Roger Fry’s Evaluations of the “Civilized” and the “Savage”’, in Christopher Green (ed.), Art Made Modern: Roger Fry's Vision of Art, exhibition catalogue, Courtauld Institute Galleries, London 1999, p.126.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeny, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.45.

See Alice Correia, ‘Mask ?1928 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2012, in, Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, 2015, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research/content/1147467?project=4 , accessed 21 April 2015 and Alice Correia, ‘Mask 1929 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2012, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, 2015, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research/content/1149252?project=4 , accessed 21 April 2015.

Henry Moore, ‘Foreword’, in Primitive African Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Lefevre Galleries, London 1933, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.99.

Henry Moore, ‘On Carving’, New English Weekly, 5 May 1932, pp.65–6, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.190.

Anne Middleton Wagner, Mother Stone: The Vitality of Modern British Sculpture, New Haven and London 2005, p.20.

See Charles Harrison, English Art and Modernism, 1981, revised edn, New Haven and London 1994, p.229; Sophie Bowness, ‘Modernist Stone Carving in England and “The Big View of Sculpture”’ in Carving Mountains: Modern Stone Sculpture in England 1907–37, exhibition catalogue, Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge 1998, p.35; Jon Wood, ‘Gods, Graves and Sculptors: Gudea, Sumerian Sculpture and the Avant-Garde, c.1930–1935’, Sculpture Journal, no.10, 2003, pp.67–82.

Henry Moore, ‘Mesopotamian Art’, in Lucienne Laroche, The Middle East, London 1974, pp.7–8, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.109.

G. Contenau, ‘L’art sumérian: les conventions de la statuaire’, Documents, vol.1, no.1, 1930, pp.1–8. At the back of the magazine abbreviated versions of each essay were provided in English. For digital facsimiles of vols.1 and 2 of Documents see http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k32951f.image , accessed 26 July 2012. Moore was an avid reader and regularly studied contemporary art periodicals and may well have been aware of Contenau’s essay.

Henry Moore, ‘Mesopotamian Art’, Listener, 5 June 1935, pp.944–6, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.101. Moore’s essay was ostensibly a review of art critic Christian Zervos’s new book L’Art de la Mésopotamie (1935).

Henry Moore, The Artist’s Hand, Much Hadham 1980, cited in Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011, p.66.

David Sylvester, ‘The Evolution of Henry Moore’s Sculpture: I’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, no.543, June 1948, p.159.

Lynda Morris and Robert Radford, AIA: Artists International Association 1933–1953, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford 1983, p.2.

Related essays

- Henry Moore and World Sculpture Dawn Ades

- Henry Moore and Stone: Methods and Materials Sebastiano Barassi and James Copper

- ‘Worthy of the great tradition’: Kenneth Clark on Henry Moore Chris Stephens

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Girl 1931 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2012, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www