Empire and the City: Early Films of London

Maurizio Cinquegrani

Camden Town painters rarely focused on the major sights of central London. By contrast, Maurizio Cinquegrani shows that filmmakers in these years chose to record the city in terms of its imperial landmarks and the free-flowing, even frenetic, movement of its crowds.

A middle class boy born in London on Queen Victoria’s coronation day on 20 June 1837 could, on his tenth birthday, have been lucky enough to visit the Zoological Gardens in Regent’s Park, which opened to the public in 1847. He could have also visited the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park or James Wyld’s Globe in Leicester Square in his early teens. As a young man turned twenty he would have read about the Sepoy Mutiny in India, perhaps in one of those illustrated magazines which often devoted their pages to events taking place in the colonies. Later he could have read serialised novels by Charles Dickens in All Year Around or Arthur Conan Doyle’s short stories in the Strand while travelling on a train boarded in one of the fourteen major railway stations which opened in London during his lifetime. The train could have taken him on a short holiday to a seaside resort like Brighton or Blackpool, or to visit relatives in Manchester, Glasgow or Liverpool. Unless he had joined the army or the civil service and travelled to distant destinations, his knowledge of the colonies would have come from shows, exhibitions, books, postcards and magazines. At the age of sixty, he would have hardly been able to dissimulate his wonder in front of the first exhibitions of moving pictures at his local music hall. In June 1897, perhaps too tired to travel to central London or unwilling to face the great crowd, he would have watched Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession on film. The new technology would gradually appear less novel, and he would realise that the themes of films were relatively familiar: exhibitions, means of transport, parades, crowded streets and representations of distant and exotic places had long been part of his experience of urban life in Victorian Britain.

Indeed, the Victorian era had witnessed the arrival of mass communication and mass visual culture, as new technologies of printing, reporting and reproduction fuelled an unprecedented expansion in the circulation of material such as newspapers, magazines and photographs. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, technological advances aimed at capturing images and motion on a light-sensitive medium led to the invention of moving-image film. Early cinema, in Britain and elsewhere, was a quintessentially urban phenomenon, and city life was a favourite subject for audiences and filmmakers. As Siegfried Kracauer has shown in his study, public spaces crowded with moving people were filmed by pioneers who were exploiting the ability of the new medium to record and reveal reality.1 In One-Way Street (1928), Walter Benjamin suggested that the moving picture ‘commands optical approaches to the essence of the city’.2 Activities such as driving through busy thoroughfares could be visually recast in films. While taking into account arguments implying that film intensified new modes of seeing and experiencing the modern city, I want to argue for a shift in focus in the study of early cinema and the city. So far the focus has primarily been on the modernity of the medium and seldom on the imperial forces which shaped cinema and were represented in films. By bringing together the domains of urban and imperial history, I hope to fill a gap in current understanding.

The music hall and early films in the age of empire

In 1889 the artist Walter Sickert had given his account of the term ‘Impressionism’ in the catalogue of the London Impressionists exhibition at the Goupil Gallery in New Bond Street:

Essentially and firstly it is not realism. It has no wish to record anything merely because it exists ... It is strong in the belief that for those who live in the most wonderful city in the world, the most fruitful course of study lies in the persistent effort to render the magic and poetry which they daily see around them.3

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford 1892

Oil paint on canvas

support: 765 x 638 mm; frame: 915 x 787 x 69 mm

Tate T02039

Purchased 1976

© Tate

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford 1892

Tate T02039

© Tate

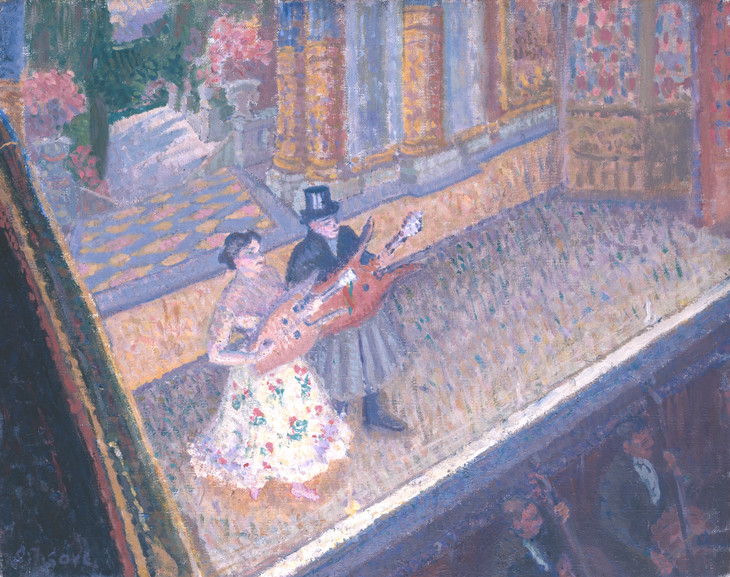

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Inez and Taki 1910

Oil paint on canvas

support: 406 x 508 mm; frame: 608 x 710 x 52 mm

Tate N05859

Purchased 1948

Fig.2

Spencer Gore

Inez and Taki 1910

Tate N05859

Pioneer filmmakers, similarly preoccupied with modernity and urban themes, aimed more typically at providing a record – although, as this essay will demonstrate, that record was also prone to be selective and at times transformative. Until the growth of picture palaces in 1909, London’s music halls were the main focus of commercial attention for early filmmakers; they were also an important subject of popular urban entertainment for Sickert from the 1880s and later for Spencer Gore too (figs.1–3).4 Sickert also captured a film screening in a music hall in 1906 in Gallery of the Old Mogul (fig.4). By 1910 there were many purpose-built cinemas in London; in 1913 Camden Town Group member Malcolm Drummond painted the shadowy world of the picture palace in In the Cinema (fig.5).

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The New Bedford c.1914–15

Oil paint on canvas

support: 914 x 356 mm; frame: 1105 x 545 x 62 mm

Tate N06174

Bequeathed by Sir Edward Marsh through the Contemporary Art Society 1953

© Tate

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

The New Bedford c.1914–15

Tate N06174

© Tate

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Gallery of the Old Mogul 1906

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 730 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Fig.4

Walter Richard Sickert

Gallery of the Old Mogul 1906

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

In the Cinema 1913

695 x 695 mm

Ferens Art Gallery, Hull

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Ferens Art Gallery: Hull Museums

Fig.5

Malcolm Drummond

In the Cinema 1913

Ferens Art Gallery, Hull

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Ferens Art Gallery: Hull Museums

And whether he’s on India’s coral strand,

Or pouring out his blood in the Sudan,

To keep our flag a flying, he’s doing and a dying,

Every inch of him a soldier and a man.7

Or pouring out his blood in the Sudan,

To keep our flag a flying, he’s doing and a dying,

Every inch of him a soldier and a man.7

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Rule Britannia 1910

Oil paint on canvas

unconfirmed: 762 x 635 mm; frame: 970 x 845 x 115 mm

Tate T06521

Presented by the Patrons of British Art through the Tate Gallery Foundation 1992

Fig.6

Spencer Gore

Rule Britannia 1910

Tate T06521

Roy Armes and Noël Burch have investigated the social and professional origins of pioneer filmmakers and defined early film production in Britain as ‘middle-class cinema’.9 Burch argues that the development of popular leisure in Victorian Britain led to the new-born cinematograph becoming a popular spectacle aimed at working-class people but run by middle-class hands.10 From its outset, British cinema was controlled by middle-class Victorian entrepreneurs, such as Cecil Hepworth, R.W. Paul, George A. Smith, James Kenyon and Sagar Mitchell, who had all previously worked as photographers or producers of photographic material and magic-lantern slides. Characters and edifying storylines in fiction films made in the period 1895–1914 often reveal the middle class origins of the filmmakers, which are also reflected in non-fiction films expressing acceptance of and often enthusiasm for imperial adventure.

According to Richard N. Price, for the lower and middle classes, imperialism was an ideology made attractive by the tensions that existed within Victorian and Edwardian societies. Love of country and empire assuaged anxieties about social and economic status caused in part by the erratic and unpredictable forces of the market.11 There were concerns about the possibility of insurrection, as urban riots, demonstrations and rallies became more prevalent. The urban mob, personified by the hooligan, posed a threat to society, and gave a physical dimension to the widespread fear of political turmoil and social unrest. This in turn prompted theories about urban decay and suggestions that national life was at risk.12 Internal threats appeared in the form of organised labour and the growing influence of socialism. From the mid-1900s external threats, such as the expansion of German maritime power and the industrial competition from America, caused concern, too.

In response to these threats, efforts were made to maintain the hegemony of the imperial ideology. These involved education, recreation and popular entertainment, which included the music hall and, from the mid-1890s, cinematography. Many filmmakers, therefore, generated an image of the city where imperial landmarks and events were part of an orderly urban space characterised by the regular movement of troops parading on the streets and the smooth movement of the newest forms of urban transport. As Lynda Nead suggests, the imperial project depended on the eradication of disorder and the regulation of the unruly spaces of the city and on the triumph of the modern over outmoded forms of society.13 Cinematic cities were essentially free from disorder and dissent, and thus a projection of the imperial rule.

Cinematic London, evocative space

Early films offer a view of a variety of cultural and political expressions of empire in the urban landscape, ranging from Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee to the display of exotic beasts from the colonies in Regent’s Park and the frenetic activity in the financial heart of the British Empire, the City of London.14 Indeed, as Felix Driver and David Gilbert suggest, turn-of-the-century London was a place in which a great number of imperial sights could be seen:

Particular aspects of empire – political authority, commercial power, cosmopolitan consumption, scientific progress, popular display – were represented by different sites such as Westminster, the City, Oxford Street, South Kensington or Wembley.15

If London was at the centre of the empire, the empire was at the heart of the modern urban experience.16 Consequently, cinematic London gives us the opportunity to study an image of the city in which the experiences of the empire and of urban modernity constantly intersect, as well as the chance to investigate the public, architectural face of the city during the heyday of British imperialism.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, British imperial identity coexisted with the weight of old tradition embodied in the monarchy, and the relationship between present and past resulted in a dialectical process of change and continuity. For example, the reinvention of the Iron Age warrior queen Boudica as an icon of female leadership and strength, as Vanessa Collingridge suggests, became a reference point for Queen Victoria and a symbol of empire.17 Once Victoria became Empress of India in 1877, all royal occasions were also imperial occasions and, as David Cannadine argues, the late nineteenth century became the age of invented traditions.18 The proliferation of monumental and commemorative buildings provided the setting for ceremonial practices, which displayed the city as inextricably linked with the monarchy, performance and the imperial theme. Finally, films contributed by making these images of urban splendour familiar to the citizens of the empire: even static cameras, as John Mackenzie suggests, managed to capture the spectacle of parades and city crowds.19

As Denis Cosgrove argues, the subject matter of nineteenth-century painted panoramas and dioramas was dominated by images of imperial cities. Actual panoramas of London were regularly offered to the public at the Regent’s Park Colosseum from 1829 and were anticipated by monumental views such as that taken in 1821 by Henry Barker and Thomas Horner from the cupola of St Paul’s using Cornelius Varley’s graphic telescope.20 The visual representation of London was constantly renewed by artists and, at the end of the century, pioneer filmmakers. The most complete extant cinematic journey through London at the turn of the century is now known as Old London Street Scenes, a film dating from c.1900.21 In this film the city emerges as the wealthy nexus of the empire. Eleven scenes filmed with a fixed camera represent as many places; in each of the following sections I shall explore its locations and draw attention to other films of the same sites.

Hyde Park Corner

The first shot of Old London Street Scenes represents horse-drawn vehicles passing by Hyde Park Corner at the west end of Piccadilly, and was filmed just a few yards away from Rotten Row, which was the subject of a painting made in 1890 by Camille Pissarro and the place where R.W. Paul in 1896 had filmed Hyde Park Bicycling Scene, one of the earliest films of London. The 1900 Baedeker guide to London and its environs informed the reader that ‘the Park is also a favourite rendezvous of organised crowds, holding demonstrations in favour or disfavour of some political idea or measure’.22 The largest of the Royal Parks was indeed a place devoted to rallies and demonstrations, and by 1850 it was known as the Park of the People. For example, in autumn 1862 several pro-Garibaldi demonstrations took place there, and in 1866 and 1884 members of the Reform League marched to the park following the defeats of the Reform Bill.23 Fenian rallies took place each St Patrick’s Day throughout the 1860s and 1870s and, in 1880, 30,000 men and women gathered in the park to demand state regulation of the laundry industry.24 Only a glimpse of this social dimension was offered when, in 1911, Gaumont produced Suffragettes in Hyde Park. This film, which is now lost, belonged to a new phase of factual filmmaking: in the early 1910s, British newsreels were produced by Gaumont and Pathé and presented a broader range of subjects.25 An earlier film such as Old London Street Scenes offers instead a view of Hyde Park as an uncontested space.

Throughout the nineteenth century Hyde Park was the setting for a number of key events in London’s history. In 1851, for example, the Great Exhibition of the Work of Industry of All Nations was staged there. The first Crystal Palace was also built there to display the latest technological developments in a 990,000 square feet (92,000 m2) space. This event attracted six million visitors to the capital and was one of the most stunning ventures of the Victorian era.26 At the end of the century Hyde Park was still associated with ceremonies, the monarchy and parades, and became a favourite subject for early actuality films. It was filmed by several filmmakers whose moving pictures of Hyde Park have not always survived. Birt Acres filmed Cycling in Hyde Park in 1896, and a year later Chard’s Vitagraph produced Hyde Park Corner. Rotten Row, Hyde Park was filmed by Cecil Hepworth in 1898 for the Warwick Trading Company, which also produced One Sort of Sunday Crowd at Hyde Park in 1900. Coaching in Hyde Park was filmed in 1909 by Will Barker. In 1911, Empire Day recorded the celebration held in the park for this imperial event.

Hyde Park was a complex urban space, and the social and class contrasts visible in the city as a whole were evident within its 350 acres. Certain areas were inhabited by prostitutes and their clients, and offered an image which was rather different from that of the upper-class Rotten Row. Henry Mayhew gave an account of park prostitution in London’s Underworld, the fourth volume of his London Labour and London Poor, which was published in 1862:

Park women, properly so called, are those degraded creatures utterly lost to all sense of shame, who wander about the paths most frequented after nightfall in the Parks, and consent to any species of humiliation for the sake of acquiring a few shillings. I was told that an old woman, whose front teeth were absolutely wanting, was known to obtain a precarious livelihood by haunting the by-walks of Hyde Park, near Park Lane.27

This underworld went unrecorded as early filmmakers gave pre-eminence to its more salubrious spaces. Hyde Park Corner was, and still is today, the monumental face of the Park, and Old London Street Scenes focuses on its gateway, built in 1828 with reliefs inspired by the Elgin Marbles. The neoclassical architecture of the gate, like the triumphal Marble Arch at the north-east corner of the park, evoked past empires and was an ideal subject for film.

Parliament Square

The second scene of Old London Street Scenes is a view across Parliament Square in Westminster filmed from Broad Sanctuary. This shot brings the viewer to the political heart of the city, and features St Margaret’s Church and what is arguably the most recognisable monumental building in London: the Big Ben clock tower (over one hundred years later, the clock tower is still regarded by Londoners as the most iconic London film location).28 Several pedestrians and horse-drawn trams can be seen on the screen.

The Houses of Parliament, recorded in this scene, were in 1900 relatively new: the older Houses of Parliament had been destroyed by fire in 1834 and the construction of the new Parliament, designed by Charles Barry, was not finished until 1871. However, Barry’s use of Perpendicular Gothic style, which embodied conservative values and evoked medieval England, revealed London’s ambivalence towards modernity. By the end of the nineteenth century, it was nevertheless a celebrated architectural landmark and it was filmed several times. In 1896 R.W. Paul filmed Houses of Parliament; in 1897 French filmmaker Alexandre Promio filmed the building from a ferry on the Thames in Panorama du Palais de Westminster pris de la Tamise. George A. Smith filmed Houses of Parliament in 1897, and Cecil Hepworth made Panorama of Westminster Palace in 1898, the same year in which Paul made Parliament Street. Filmmakers portrayed a monumental space filled with symbolic and ritual meaning: by filming the political centre of the empire they contributed to promoting an iconography of political power embodied in London’s built environment and its visual representations. Avoided by the Camden Town Group artists, the Houses of Parliament were famously painted in 1904 by Claude Monet. Here, natural elements such as sunlight, mist, fog and water are more tangible than the building itself, and the urban landmark blurs with the surrounding space.

The River Thames

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Victoria Embankment Gardens 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 664 x 461 mm; frame: 788 x 590 x 50 mm

Tate T03841

Purchased 1984

© The estate of Charles Ginner

Fig.7

Charles Ginner

Victoria Embankment Gardens 1912

Tate T03841

© The estate of Charles Ginner

In 1898 the same subject was filmed by Cecil Hepworth in Westminster Steam-Boat Pier and by R.W. Paul in Panorama of London Streets (Embankment). Charles Urban later produced The Thames: Westminster to Greenwich (1910), a boat trip from Lambeth Bridge to south-east London. In 1909 two boat trips were filmed by Gaston Quiribet for Hepworth in The Thames in Winter and Moonlight on the Thames. In the same year Will Barker filmed for the Warwick Trading Company a more fitting imperial image of the Thames: The Great Thames Pageant represented the Home Fleet arriving in the Port of London. Urban filmed the same event, and his film includes scenes of battleships and submarines. In several early actuality films, the river was filmed from the shore, giving particular attention to the municipally owned steamers, which were inaugurated in 1905, and to the modern bridges and their lively traffic scenes. In 1896 Westminster Bridge, built thirty-four years earlier, was filmed by Promio, R.W. Paul and Esmé Collings. In the same year, Paul also shot a busy scene on Blackfriars Bridge, Rush Hour Record on London Bridge and Traffic on Tower Bridge. The latter represents the most recent and original bridge on the Thames, completed in 1894 and destined to become another iconic London location. The City of London Corporation, the municipal governing body of the City of London, commissioned the building of Tower Bridge when the East End became so densely populated that a new bridge east of London Bridge became necessary. Early actuality films representing the bridge and the steamers thus exemplify municipal power in late Victorian London. Tower Bridge, which represented an attraction for Londoners, tourists, filmmakers and audiences alike, was also filmed in 1896 by Promio and Birt Acres in Pont de la Tour and Tower Bridge Working. A few years later, Will Baker filmed Panorama of the Tower of London and Tower Bridge for the Warwick Trading Company (1904).

Waterloo Place and Trafalgar Square

Two of the following three shots of Old London Street Scenes bear a straightforward military and imperial message, as they represent monumental sites celebrating the military achievements of the empire. The first of the two shots briefly depicts John Henry Foley’s Crimean War Memorial in Waterloo Place, located at the junction of Lower Regent Street and Pall Mall.31 In 1900 Britain was engaged in a new war in South Africa; the image of a monument commemorating the heroes of an earlier war therefore put forward a strong military message. Old London Street Scenes then continues with a brief shot of Charing Cross Station, beneath whose arches was the famous Gatti’s Hungerford Palace of Varieties (where a music-hall performance by Katie Lawrence was painted by Sickert in c.1903). This scene in the film is followed by a view of Pall Mall and Trafalgar Square. Horse-drawn carriages move from the background to the foreground, and the National Gallery can be seen.

Trafalgar Square and Nelson’s Column are among the most outstanding landmarks in London and the most popular destinations for its visitors. The Square was also the subject of I live in Trafalgar Square, a very popular music-hall song written by Clarence W. Murphy in 1902:

I live in Trafalgar Square

With four lions to guard me

Fountains and Statues all over the place

And the metropolis staring me right in the face.

With four lions to guard me

Fountains and Statues all over the place

And the metropolis staring me right in the face.

Thanks to its location at the intersection of Pall Mall to the west, Whitehall to the south, and the Strand and Fleet Street to the east, Trafalgar Square was indeed the meeting point of the British monarchy, government and commerce. The Square was completed in 1845 and in the nineteenth century, just like today, it was considered the heart of London, the midpoint between the City and Westminster. The first moving picture of the square was made in 1890 by Wordsworth Donisthorpe and William Carr Crofts, two British inventors and pioneers of photography.32 Ten frames from their film have survived representing water surging from one of the fountains framed against a background of the National Gallery, with pedestrians and horse-drawn omnibuses. In 1897 R.W. Paul filmed the same subject in Fountains. Throughout the 1890s the London County Council pursued the control of water, and in 1903 the Metropolitan Water Board was founded, thereby bringing under a single public body nine private water companies supplying water to London.33 In several early films, Trafalgar Square fountains could also be seen as a demonstration of municipally owned water supplies, with their constant jets of water communicating opulence and the power of the municipal authority.

On 21 October 1897 the celebrations for the ninety-second anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar were filmed by William K.L. Dickson for Mutoscope and Biograph (The Nelson Column), Cecil Hepworth for the Warwick Trading Company (Trafalgar Day in London), George Albert Smith (Nelson’s Monument) and W. Watson & Sons (Trafalgar Day). In 1909 Gaston Quiribet filmed City of Westminster for the Hepworth firm, which is a ride filmed from a car on the streets of Westminster, from Whitehall to St Martin’s Place. Trafalgar Square appears here not only as the physical centre of the city, but also as one of its most lively places. City of Westminster emphasises the Square’s importance in the urban environment by documenting the presence of a great number of automobiles, omnibuses, trams and pedestrians in the area. Nelson’s Column is filmed with a vertical shot from its base to the statue of Admiral Nelson at the top of the column.

As Rodney Mace explains in his 2005 study, the Square was a contradictory location, designed as an imperial space and later established as a site of political demonstrations, as its imperial iconography provided a target for those who challenged the established order.34 During the 1880s the Labour movement, in particular the Social Democratic Federation, held rallies in Trafalgar Square. On 8 February 1886 a major rally against unemployment led to riots in Pall Mall. Later that year, on 13 November, thousands marched to the Square to demonstrate against coercion in Ireland; due to the violent reaction of the police, that day would become known as ‘Bloody Sunday’.35 At the beginning of the twentieth century there were demonstrations in the Square about suffrage reform and one of these, organised by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, was the subject of a film produced by the Warwick Trading Company on 13 June 1908: The Suffragette Demonstration. This film is something of an exception: demonstrations and riots were largely absent from the cinematic representations of the Square comemorating Nelson’s victory at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Trafalgar Square was an ambivalent space embodying elements of both power and disorder, but the cinematic image emerging from most films listed here reflected its iconic identity as symbol of political power and civic pride.

Fleet Street and the Strand

The two following shots of Old London Street Scenes represent Fleet Street and the Strand: in the first we can see the nineteenth-century Gothic Law Courts, while the second represents a crowded, traffic-choked part of the Strand near the Lyceum Theatre, with St Mary le Strand in the background. Its crowd and traffic suggest the importance of the Strand in London’s topography. Patrick Joyce has investigated practices of movement in the city and explained the role played by the Strand:

The living stream of London is above all that which flows in and out of the city every day, increasingly the commercial City itself, and which is in fact to be encountered most clearly at the place where this tide ebbs and flows most, fittingly enough called the Strand.36

More broadly, Joyce has suggested that the nineteenth-century city was experienced in new kinds of ways and that the stream of the city, including the ritual of going to work and of leisure, was part of the experience of everyday life in the city.37 This scene from Old London Street Scenes records the ritual of going to work through a vital artery of London, where thousands of people walk to the City from Charing Cross Station. In 1904 Clarence W. Murphy and Harry Castling described this most lively of London streets in the music-hall song Let’s All Go Down the Strand:

Oh! What a happy land.

That’s the place for fun and noise,

All among the girls and boys.

So let’s all go down the Strand.

That’s the place for fun and noise,

All among the girls and boys.

So let’s all go down the Strand.

Physical business transactions between the City and Westminster depended on communication between these two areas. The importance of the Strand was reflected in the city authorities’ plans to redevelop the thoroughfare by demolishing the narrow alleys near it. In 1900 a portion of the slum property between the Strand and Holborn (such as the buildings occupying Holywell Street) was demolished to make way for Aldwych and Kingsway.38 In contrast to narrow alleys like Holywell Street, wide streets such as Kingsway and the Strand allowed for free public passage on a greater scale. An aspect of international rivalry and inspired by Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s rebuilding of Paris, the planning of these streets can be seen as London’s answer to the wide boulevards of other imperial capitals. As Old London Street Scenes exemplifies, filmmakers seeking an imperial image of the city were thus attracted to wide thoroughfares like the Strand. On the other hand, the slum district running north of and parallel to the Strand was never recorded by filmmakers who consistently avoided the insalubrious districts of the city.

The City of London

The last three shots of Old London Street Scenes bring the viewer into the heart of the Square Mile. A view of the Mappin and Webb building at Poultry is filmed from an elevated position looking towards Cannon Street and the bell tower of St Mary le Bow can be seen in the background. This shot is followed by two street scenes outside the Bank of England and the Mansion House. Union flags are waving on horse-drawn omnibuses, and the dense traffic in Queen Victoria Street and Threadneedle Street reflects the identity of the City as the commercial and financial nexus of the empire, its frenetic source of economic power. The activities undertaken in this space contributed to the definition of imperial London, as Jonathan Schneer suggests, by cementing the City’s role as a financial and commercial metropolis and encouraging the government to pursue an imperial policy.39 The film ends with a shot of the area in front of the Lord Mayor’s residence, the Mansion House, taken from a window of the Mappin & Webb building at Poultry. If each of the eleven scenes composing Old London Street Scenes reveal how crowded and frenetic late Victorian London was, these three shots of the City reveal the busiest district of all, with the highest number of people and vehicles of various kinds on the streets. In particular, the final shot displays an endless flow of carriages, people and horse-drawn trams with banners and posters advertising Nestlé and Mellin’s products.

Niels Moeller Lund 1863–1916

The Heart of the Empire 1904

Oil paint on canvas

1372 x 1829 mm

Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London

Photo © City of London

Fig.8

Niels Moeller Lund

The Heart of the Empire 1904

Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London

Photo © City of London

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 813 x 660 mm; frame: 939 x 786 x 65 mm

Tate T03096

Purchased 1980

© The estate of Charles Ginner

Fig.9

Charles Ginner

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Tate T03096

© The estate of Charles Ginner

Charles Ginner painted Piccadilly Circus in 1912 (Tate T03096, fig.9), but urban landmarks were normally avoided by the Camden Town Group artists. Nevetheless, the modernity of the imperial city equally emerges from films of its landmarks and from paintings of an urban experience that was less concerned with imperial iconography, and instead with interiors, suburban streets and gardens.

Notes

Siegfried Kracauer, Theory of Film: the Redemption of Physical Reality, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1997 (first edition 1960), pp.31–3.

Walter Sickert, ‘Impressionism’, in A Collection of Paintings by the London Impressionists, exhibition catalogue, Goupil Gallery, London 1889, in Anna Greutzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, p.60.

On film exhibition in London, see also Jon Burrows, ‘Penny Pleasures: Film Exhibition in London During the Nickelodeon Era, 1906–1914’, Film History, vol.16, no.1, 2004, pp.60–91, and ‘Penny Pleasures II: Indecency, Anarchy and Junk Film in London’s “Nickelodeons”, 1906–1914’, Film History, vol.16, no.2, 2004, pp.172– 97.

Peter Bailey, Popular Culture and Performance in the Victorian City, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York 1998, p.150.

Quoted in John M. Mackenzie, ‘Empire and Metropolitan Cultures’, in Andrew Porter (ed.), The Oxford History of the British Empire: The Nineteenth Century, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1999, p.278.

Roy Armes, A Critical History of the British Cinema, Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1978, p.17; Noël Burch, Life to Those Shadows, BFI Publishing, London 1990, p.92.

Richard N. Price, ‘Society, Status and Jingoism: The Social Roots of Lower Middle Class Patriotism, 1870–1900’, in Geoffrey Crossicck (ed.), The Lower Middle Class in Britain 1870–1914, Croom Helm, London 1977, pp.89–112.

See Steve Attridge, Nationalism, Imperialism and Identity in Late Victorian Culture: Civil and Military Worlds, Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2003, pp.107–8.

Lynda Nead, Victoria Babylon: People, Streets and Images in Nineteenth-Century London, Yale University Press, New Haven 2000, pp.194–5.

See Maurizio Cinquegrani, ‘The Nexus of the Empire: Early Actuality Films of London at the Turn of the Twentieth Century’, Journal of British Cinema and Television, vol.6, no.1, 2009, pp.207–19.

Felix Driver and David Gilbert, ‘Imperial Cities: Overlapping Territories, Intertwined Histories’, in Felix Driver and David Gilbert (eds.), Imperial Cities: Landscape, Display and Identity, Manchester University Press, Manchester 2003, p.1.

Ibid., pp.2–3. See also Felix Driver and David Gilbert, ‘Heart of Empire? Landscape, Space and Performance in Imperial London’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol.16, no.1, 1998, pp.11–28.

Vanessa Collingridge, Boudica: The Life of Britain’s Legendary Warrior Queen, Overlook Press, New York 2007, p.355.

David Cannadine, ‘The Context, Performance and Meaning of Ritual: The British Monarchy and the Invention of Tradition, c.1820–1877’, in Eric Hobsbawm and Terrence Ranger (eds.), The Invention of Tradition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2000, p.124.

Denis Cosgrove, Apollo’s Eye: A Cartographic Genealogy of the Earth in the Western Imagination, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2001, p.206.

There are no available credits for Old London Street Scenes, which is a title of convenience devised by an archivist. In my opinion, Old London Street Scenes is likely to be an incomplete version of the Warwick Trading Company series London Street Scenes. Warwick’s London Street Scenes seems to be the only recorded film to include, like Old London Street Scenes, sequences of Waterloo Place. Most of the remaining scenes can also be matched with those of London Street Scenes.

Karl Baedeker, London and Its Environs: An Handbook for Travellers, Karl Baedeker, Leipzig 1900, pp.333–4.

Seth Koven, Slumming: Sexual and Social Politics in Victorian London, Princeton University Press, Princeton 2004, p.165.

See Luke Mckernan, Topical Budget: The Great British News Film, BFI Publishing, London 1991, pp.1–5. During the early 1910s at least two more newsreels of political demonstrations displayed a less imperial urban space: London: Factory Girls on Strike in Camden Town (1911) and London: The Coal Strike March (1912).

Caroline Arscott, ‘The Representation of the City in the Visual Arts’, in David M. Palliser, Peter Clark and Martin Daunton(eds.), The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, vol.3: 1840–1950, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2000, pp.817–20.

The memorial was considerably changed by Arthur George Walker in the 1910s and unveiled in 1915. The original statue of Sidney Herbert, who was responsible for the War Office during the Crimean War, became part of a larger memorial, including the statue of Florence Nightingale.

Their film was photographed at ten frames per second on celluloid, with a camera called Kinesigraph. See Denis Gifford, The British Film Catalogue: Non-Fiction Film, 1888–1994, third edn, Fitzroy Dearborn, London 2001, p.3, and Stephen Herbert, Industry, Liberty and a Vision: Wordsworth Donisthorpe’s Kinesigraph, The Projection Box, London 1998.

See Andrew Saint, Politic and People of London: The London County Council 1889–1965, Hambledon Press, London 1989.

Jonathan Schneer, London 1900: The Imperial Metropolis, Yale University Press, New Haven 1999, pp.64–92.

Maurizio Cinquegrani completed a doctorate on early films of the cities of the British Empire at King’s College, London, 2010.

How to cite

Maurizio Cinquegrani, ‘Empire and the City: Early Films of London’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www