‘A stimulation to greater effort of living’: The Importance of Henry Moore’s ‘credible compromise’ to Herbert Read’s Aesthetics and Politics

Ben Cranfield

Moore’s work can be understood as a vital part of the aesthetics and politics of Herbert Read, one of the most important theorisers of art and culture in Britain in the mid-twentieth century. This essay explores why Moore came to occupy an exemplary position in Read’s thoughts about the relationship of the individual and the community.

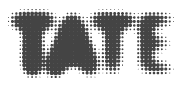

Photograph of Herbert Read, taken in 1943, at his home in No.3 The Mall, Parkhill Road, Hamstead, where he was a close neighbour of a number of artists, including Henry Moore

National Portrait Gallery, London

Photo: Howard Coster

Fig.1

Photograph of Herbert Read, taken in 1943, at his home in No.3 The Mall, Parkhill Road, Hamstead, where he was a close neighbour of a number of artists, including Henry Moore

National Portrait Gallery, London

Photo: Howard Coster

As art historian Michael Paraskos has noted, it is curious, given his tremendous output and his importance in the introduction of many key figures and ideas to Britain, that Read fell into obscurity so quickly after his death in 1968.6 The events of that year, in which Read participated posthumously with the publication of an essay on ‘Internationalism’ in the short-lived magazine of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA),7 seem a fitting epitaph to Read’s life-long commitment to radicalism. It therefore appears strange that as students reached for Marcuse, McLuhan and Mao in 1968 they did not also grasp for Read’s Poetry and Anarchism (1938) or the essays that made up the last of his collections published in his lifetime, Art and Alienation (1967). There are perhaps two main reasons why Read was overlooked by the rebelling students of British universities and art schools and why a wider neglect of his work set in that left Read in need of subsequent ‘reassessment’ and ‘re-reading’.8 Firstly, there is Read’s writing itself. Rather than the explication of a coherent philosophy, his prolific output is the record of an active mind in constant flux – evolving and developing, never linearly and certainly not systematically. Consequently, it is virtually impossible to pick up any single essay by Herbert Read and discern his complete position or viewpoint – political or aesthetic. Whilst he is always clear, reading Read is a palpable experience, as one has to follow a process of push and pull.9 One cannot so much use Read’s work as a theoretical tool, as observe his intellectual process. Secondly, and probably more importantly for Read’s immediate legacy, was the way in which he became inextricably bound up with the art that he championed most strongly and thus increasingly distanced from emerging artistic practice. It is perhaps misleading that Read’s most enduring phrase as an art critic was his definition of a new generation of British sculptors presented in the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1952 as ‘geometrists of fear’. In fact, this phrase was full of ambivalence on Read’s part. He was undoubtedly impressed by the work of the sculptors, including Lynn Chadwick, Reg Butler, Eduardo Paolozzi and William Turnbull and saw in their work expression of an existential angst with which he had much sympathy, but he was unsure of the value of work that merely reflected the fractured and disengaged state of humanity under conditions of war and advanced industrialisation.10 ‘Geometry of fear’ was an accolade and an admonishment. Indeed, Read became increasingly concerned by the tendency of contemporary art to exhibit ‘fragmentation and frustration’11 and he dismissed brutalism as an aesthetic produced by ‘economic functionalism’.12 For an emerging generation of artists, including those he wrote about and supported in many of his institutional roles, it was clear that Read’s predilections and sympathies were not for an art of contemporary reflection, but for the kind of British abstract modernism that constituted Read’s second most important artistic training ground, the grouping called Unit 1 that was active between 1933 and 1935.13 Although the radicalism of Unit 1 was at the time unquestionable (Read saw in their work far greater daring and experiment than in many of the leading protagonists of continental modernism), to a post-war generation Read’s favoured artists were bound-up in a trajectory of modernism aligned with a universal humanism that denied some of its most radical sources such as futurism and dada.14 While it would be completely misleading to suggest that there was a clean break between a pre-war British modernism and a post-war, rapidly developing, contemporary art field,15 Read’s ubiquity and the canon he supported had become problematic for the younger generation. And there was one artist, more closely associated with Read than any other, who embodied the dominant position of mid-century British modernism from which the younger generation sought to break free: Henry Moore.16

Herbert Read and Henry Moore were not just connected by their ubiquity within the canonical formation of mid-twentieth century modernism and their over-exposure as doyens of British art: the development of their respective work as critic and artist was enmeshed for nearly forty years, from the first time Read visited Moore’s studio in 1931 to Read’s death in 1968. Such was the centrality of Moore’s work for the development of Read’s philosophy of art that it is impossible to appreciate the connections within Read’s diverse output without considering how Moore’s sculpture came to signify the centre of Read’s artistic universe and, at the same time, became the symbolic cornerstone of Read’s ‘aesthetic politics’.17 Moore’s work was consistently used by Read as exemplar of an artistic modernism that reconciled the dualities of art. Whilst by no means the only contemporary artist Read used within the development of his aesthetic philosophy (Naum Gabo, Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, Henri Matisse, Paul Klee, Pablo Picasso and Jean Arp, were also key), Moore remained more solidly in Read’s favour than any other artist, contemporary or historic. What is perhaps most striking about Read’s long-term engagement with Moore’s work is that it always remained above his critical censure. In contrast, Read had a long-term critical dialogue with Gabo, whom he viewed with admiration but with concern over his commitment to a constructive abstraction – dismissed by Read, in final assessment, as Platonic idealism.18 Even Picasso came in for critical scrutiny, with Read seeing his major work Guernica 1937 as overly reliant on clichéd symbolism, even if saved from banality by Picasso’s ‘genius’ of stylistic interpretation.19 Moore’s work was never quite grasped in the same way between Read’s critical teeth. Rather, Read described Moore’s work and process in the manner of Vasari, the Renaissance father of biographically dominated art history, tellingly the story of genius as an unfolding and indisputable fact.

Arguably, this a-criticality did Moore a disservice – it smoothed the struggles, failures, tensions in the work, into something almost too perfectly synthesised. This is the great contradiction of Read’s contribution to Moore’s legacy; he did more than any other critic to promote, push and secure Moore’s unassailable reputation as Britain’s most important modern artist, but, in so doing, he left Moore as a monument to modernism, smoothed of imperfection, in a state of almost classical idealism that was, in fact, inimical to all that Read practiced within his work and admired in Moore’s, namely texture, organic development and vitality.

Arguably, this a-criticality did Moore a disservice – it smoothed the struggles, failures, tensions in the work, into something almost too perfectly synthesised. This is the great contradiction of Read’s contribution to Moore’s legacy; he did more than any other critic to promote, push and secure Moore’s unassailable reputation as Britain’s most important modern artist, but, in so doing, he left Moore as a monument to modernism, smoothed of imperfection, in a state of almost classical idealism that was, in fact, inimical to all that Read practiced within his work and admired in Moore’s, namely texture, organic development and vitality.

In this essay I do not aim to examine the extent to which Read may have influenced Moore,20 nor to establish the specific moments in which Moore may have informed Read’s thinking. One can only speculate as to whether Read would have developed different aesthetic theories had he not encountered Moore’s work at a crucial moment in his career as a critic. My goal instead is to understand why and how Moore’s work occupied such a significant place within Read’s complex aesthetic and political philosophy. Or, to put it another way, to use the vital place of Moore’s work within Read’s aesthetics to explore the interconnections of Read’s diverse output as critic and theorist.

First encounter: a return to the material

To understand why Moore was so important to Read’s work and why he transcended Read’s critical writing, taking his place, instead, at the centre of Read’s philosophy of art, it is necessary to go back to Read’s first written engagement with Moore. When Read visited Moore’s home for the first time in 1931 he had been remarkably quiet during the visit, leaving Henry and his wife Irina with the impression that he had perhaps not liked what he had seen. The next day, however, Moore received a letter from Read expressing his unreserved enthusiasm for the work and shortly afterwards, in his recently acquired role as the main writer on visual arts for the BBC’s Listener magazine, Read produced his first piece on Moore’s work.21 As was usual with his Listener pieces, this was an exhibition review, in this case, of Moore’s show at the Leicester Galleries. Here Read set out his position on the importance of Moore’s work which, although developed in different directions, was to remain for the rest of his life: ‘We may say without exaggeration that the art of sculpture has been dead in England for four centuries; equally without exaggeration I think we may say that it is reborn in the work of Henry Moore, now on exhibition at the Leicester Galleries.’22

The deathly state from which Moore’s work made a radical departure was that of mannerism and academicism, which Read believed had robbed sculpture of its most vital qualities, a view that, in part, followed that of the critic and painter Roger Fry.23 Moore broke the tyranny of this long-standing academic tradition by having ‘no regard at all for the appearance of the object (if there is one which inspires his work of art).’ Rather, ‘his first concern is for his material.’ Pursuing a line of argument that fell just short of the American critic Clement Greenberg’s future idea of medium specificity and developed out of Ruskin’s idea of truth to material, Read declared that ‘each branch of art should have its peculiar principles, determined by the nature of the material worked in, and by the function which the finished work is to fulfil.’ In the case of sculpture, this was ‘the art of carving or cutting a material of relative hardness.’24 The focus on material meant that sculpture became an art not of ‘reduplication’, of the reproduction of ‘form and feature’ from nature into another material, but ‘the translation of meaning from one material into another material.’25 This notion of the discernment of a material essence (or, rather, a materialised essence) and its alteration within its realisation by the artist in new material form importantly provided a space for the artist as creative agent, without abandoning the specificity of the situated encounter.

The sense that emerges from Read’s initial engagement with Moore’s sculpture is the importance of the creative act as a mediation of forces. There was the force of sense impressions on the artist in the original act of observation, mediated by the force of the artist's intuitive interpretation, that, in turn, met the force of the sculptural material with its own vital energy: ‘If you are translating form in one material into form in another material, you must create that form from the inside outwards.’26 The successful sculpture emerged, then, as the subtle balance of these forces: a harmony, with just enough individuation and metered against a sensitivity to material and nature – what the German philosopher and writer Goethe may have termed a ‘delicate empiricism’, or the American philosopher and psychologist William James a ‘radical pragmatism’.27 Although Read was later to abandon such a specifically technical definition of sculpture as primarily an art of carving, to focus on the experience of sculpture and its conception in the mind of the artist – a change that was influenced by an understanding of Moore’s developing working methods – Read never completely left behind the sense that the value of sculptural work was a record of an encounter between artist and material, full of tension, empathy, harmony and compromise.

Read, of course, acknowledged that Moore had not broken the spell of academicism in sculpture singlehandedly and cited the influence of Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill, Constantin Brancusi and Ossip Zadkine. However, Moore ‘in virtue of his sureness and consistency, springs straight to the head of the modern movement.’28 Indeed, in this first critical reception by Read, it was Moore’s surety, focus and sense of purpose that marked him out as the most significant sculptor of modern times: ‘Whatever may be the reaction of the average man to the originality of these works of art, he will be bound to recognise in them the expression of a consistent purpose of great force, a personal will to dominate material and form that refuses to be balked by any conventions.’29

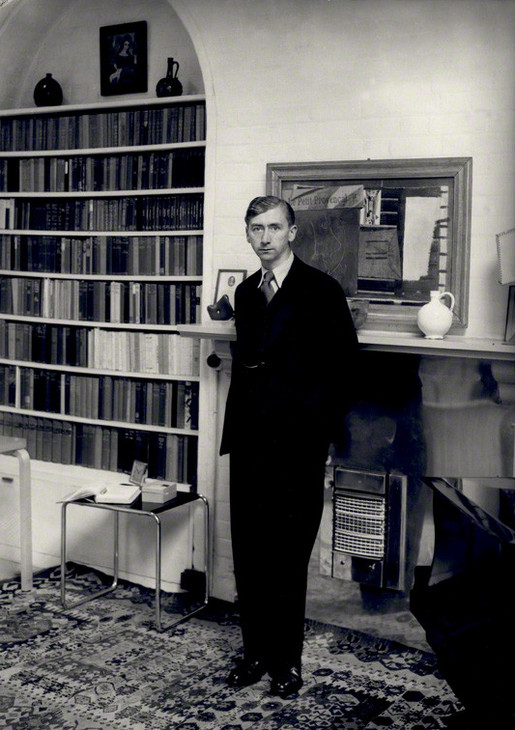

Front cover of the first monograph on Henry Moore, with an appreciation by Herbert Read, 1934

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Front cover of the first monograph on Henry Moore, with an appreciation by Herbert Read, 1934

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

It is noteworthy that it was not the particular subjects of Moore’s sculpture, not his ‘archetypal’ themes that appealed to Read at this point. In this first flush of enthusiasm, it was Moore’s Nietzschean will to power, with an un-Nietzschean emphasis on physical force and domination – language more at home in a futurist manifesto than in an exhibition review for the Listener – that singled out Moore for attention.30 Here the dynamic for Read’s engagement with Moore as a model artist was set between the artistic ego exerting its will and the artist as medium for other forces, natural, unconscious, proto-social and material.

Such a sense of Moore’s work as an exertion of artistic will over material, boldly breaking with convention and pushing sculpture further than the previous great modernist sculptors Rodin, Brancusi, Gill or Epstein, was present in Read’s first extended essay on Moore, written four years later. In his ‘appreciation’ of the artist, Read undertook a more systematic and thorough investigation of Moore’s work than had been possible in his initial review. However, the essential theme of Moore’s mastery over material and his pull away from mimesis towards translation remained, as did a belief in Moore’s singularity of conviction within his practice. The essay ended with the unequivocal remark that in Moore’s work there had ‘been no compromise’.31 Just over ten years later, Read revised and extended the 1934 essay for his introduction to a survey of Moore’s work (fig.2), which, indicative of the importance of his work for Read, was subsequently reprinted in 1954 in his collection The Philosophy of Modern Art. However, the uncompromising carver, dominating his material with hammer and chisel, was then replaced by an artist as conceptual as he was craftsman, whose ‘whole art consists in effecting a credible compromise between these forms and the concepts of his imagination.’32 By no-means the most egregious or significant shift in Read’s thinking over the course of his career, this identification of Moore, first as uncompromising realiser of ‘his conceptions in the forms natural to the material he is working in’ and then as effector of an important and necessary compromise between a visionary ideal and the pragmatics of material actualisation, may give pause for thought.33 Between these two statements a picture of Moore emerges as the uncompromising compromiser, singularly pursuing the mediation of multiple positions, forces and tensions.

Moore’s uncompromising compromise and Read’s aesthetic axis

The significance of Moore’s ‘compromise’ for Read lies in a series of dualities that, at times interchangeable, overlapped and interplayed to form the backbone of Read’s philosophy of art. If Read’s ideas about art and its most significant forms were to change throughout his life, the process of his aesthetic philosophy as a constant meditation upon and moving between the opposing forces of his favoured binaries and dualisms did not. Fundamental was a battle between classicism and romanticism, as witnessed both in discussions of the Leeds Art Club and his particularly formative relationship with the poet T.S. Eliot. As art historian David Thistlewood has explained, Read’s engagement with these polarities was initially conducted within the arena of poetry, where his own shift in thinking was influenced by those around him also struggling within their own work. For example, while initially sceptical, Read gradually took on board ‘the path Richard Aldington’s poetry had followed, from the hard, classic precision of imagism towards a “looseness of structure, texture and idea,” and a “conscious tapping of the unconscious”.’34 In the late 1920s Read had been on the side of classicism, attempting to frame the early nineteenth-century poet William Wordsworth as the progenitor of, in Thistlewood’s words, ‘a great classic movement still gathering strength in the twentieth century’,35 and seeking in his own work, which at this time was primarily poetry, a kind of formalism in which a ‘chunk of poetic process [is] carved into geometrical shape’.36 As poet and scholar Kieron Winn has argued, Read’s poetry of the 1920s is characterised by a desire to impose a modernist classicism upon romantic subjects.37 For example, when Read writes ‘The teas’d fibrils of reason/ Weave vainly to dam/ Some bank against the giant flood/ Of this emotion’, in his poem ‘The Analysis of Love’ (1923), Winn notes ‘passion, indubitably romantic in its nature, is analysed in tight, logical terms.’38 In the mid-1920s this tension between the classical and romantic became more pronounced as Read began to separate himself from Eliot and took a greater interest in the role of psychology and, particularly, Freud’s theory of the unconscious.39 As Thistlewood explains, at the beginning of the 1930s Read made his first sustained attempt to put down on paper his developing aesthetic theory of axial compromise, Form in Modern Poetry, he suggested that ‘in an authentic individual creativity, romantic and classic aspects would necessarily interfuse’.40 It is this emerging theory of inter-fusing that can be observed in Read’s appreciation of Moore’s balancing of artistic will and integrity to material. However, as Read’s use of carving as metaphor for his own, early, poetic process reveals, it was Moore as the imposer of the order of the mind onto the chaos of material that initially appealed to him. This was the quality of Moore as an abstract artist, as one who connects with the forces of the universe and ‘can make this ambience actual.’41

As Read developed his understanding of the unfolding (he would never have said progression) of modern art, the most significant guiding axis was that of Wilhelm Worringer’s Abstraction and Empathy.42 Whilst it is possible to see this as simply alternative terminology for the classical/romantic binary, the psychological orientation of Worringer’s pairing instantly appealed to Read as a more acceptable language with which to explore the dualism of art of all periods and, especially, that of the modern epoch. Read’s guide in Worringer’s important binary was poet and philosopher T.E Hulme, whose work Read edited after the former’s untimely death in 1917. It was via Hulme’s reading of Worringer that Read began to develop a belief in abstraction as a withdrawal from the physical world into the spiritual and metaphysical, with empathy, its opposite, a fully-fledged engagement in the world, a kind of realism. Worringer regarded abstraction as the paramount tendency in the modern epoch.43 Crucially, Worringer did not express a moral preference for either abstraction or empathy, but saw their appearances in art’s history as related to differences in historical periods and their concomitant psycho-social experiences.44 This idea of the correlation between aesthetic response and worldly experience was crucial to the development of Read’s notions of the centrality of art to society.45 Later, the relationship between context, psychology and aesthetics was picked up from Read’s work, as influenced by Worringer, by psychoanalytic theorist Anton Ehrenzweig, who argued that the emergence of a ‘primitive’ sensibility in modern art was not a consequence of mere stylistic copying or fashion but was due to similar socio-historic conditions that produced similar psychological and, therefore, aesthetic responses.46 Read, for his part, mobilised Worringer’s notion of an historically grounded aesthetic, pushing and pulling between the idealism of abstraction and the humanism of empathy, not just to identify the primary characteristics of an age, as Worringer had done, but to explain the appearance of differences within the body of work of an individual artist.47 Whether using Worringer, or later Ehrenzweig,48 Read always believed that art was a reflection of complex forces that were beyond the conscious influences of the artist.

As Read increasingly became the primary arbiter for modern art in Britain, Worringer’s binary was frequently replaced by that of abstraction and superrealism. Read’s persistent use of the word superrealism was not just a perverse desire to provide an English term for surrealism (although Read did originally provide the term in order to make his meaning clear to an English speaking public), but an attempt to ‘make a distinction between superrealism in general and surrealism in particular, employing the first word for the tentative and historical manifestations of what has now become a conscious and deliberate artistic principle.’49 In his introductory essay to the International Surrealist Exhibition held in London in 1936, he had aligned superrealism with romanticism. He presented surrealism, with its long tail of superrealist tendencies, in relation to the classical/romantic binary, but not to mediate again between these two poles, or, as had been his aim within his poetry of the late 1920s, to integrate them, but to resolve the conflict through the dismissal of the classical altogether:

So long as romanticism and classicism were considered as alternative attitudes, rival camps, professions of faith, an interminable struggle was in prospect, with the critics as profiteers. But what in effect surrealism claims to do is to resolve the conflict – not, as I formerly hoped, by establishing a synthesis which I was prepared to call ‘reason’ or ‘humanism’ – but by liquidating classicism, by showing its complete irrelevance, its anaesthetic effect, its contradiction of the creative impulse. Classicism, let it be stated without further preface, represents for us now, and has always represented, the forces of oppression. Classicism is the intellectual counterpart to political tyranny.50

In fact, this was not to be Read’s last word on classicism, but this, one of Read’s most unequivocally partisan statements in his dualistic approach to art, revealed what he believed to be art’s most important functions: the realisation of a creative freedom, the incitement towards life and, most crucially, the liberation of the individual from the tyranny of ideals and absolutes. Moore had been included in the 1936 surrealist exhibition and was certainly, from Read’s perspective, part of the broader superrealist tendency that he was interested in identifying.51 However, while included within the triumph of superrealism, Moore, along with Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, occupied a more complex position within Read’s aesthetics. The way in which their work moved along the aesthetic axis, or, in Moore’s case, occupied a central position, led to Read’s assertion that ‘it has always seemed to me that the opposition which we make in critical theory between reason and romanticism, and in wider philosophical terms between pragmatism and idealism, cannot be resolved and should not be resolved.’52 This position may not be as contradictory of Read’s statement on surrealism’s triumphant ‘liquidating’ of classicism as it appears. Read believed superrealism to be a kind of realism and, for him, reality was the same as truth. Crucially, he saw that truth could only be approached as an ever-receding end-point of a critical dialectical process.53 Therefore, his commitment to a constantly dynamic critical dialectics was part of the very same impulse that declared the liquidation of classical idealism. Within Read’s critical dialectical approach to his philosophy of art, Moore represented a stillness at its centre, the forger of the artistic balance between ‘coalition of idea and material’.54

It may be tempting to see this fine balance as a kind of mediocrity, with Moore solidly occupying a middle ground – neither fully surrealist, nor fully abstract.55 Not helping to dispel the notion of his position as one of benign compromise, Moore commented every so often that one needed to temper more extreme abstractions with a kind of realism in order to keep public sympathy. This, however, was not the credible compromise that Read admired in Moore’s work. The works that Read seems to have been particular drawn to did not present a singular resolution of the overall problem of the dualism of modern art, but, rather, presented individual and particular compromises between pragmatic concerns and ideal aims.

The problem of sculpture: Moore’s pragmatic process

Unsurprisingly, Moore was central to Read’s most sustained meditation on sculpture, The Art of Sculpture (1956).56 The opening chapter addressed a familiar story of sculptural development: the detachment of ornament from architecture. Read told the story of how sculpture finally came down from the cornices and away from the enclaves and realised its own function as non-architectural three-dimensionality. While Read identified Moore as the exemplar of sculpture’s independence, it was in fact Moore’s ability to approach what Read considered impossible – the successful integration of modern sculpture and architecture – that marked Moore out as the master of synthesis. In a commission, recently finished at the time of Read’s writing, for a permanent piece of sculpture to adorn the new Time-Life building in Bond Street, Moore had produced a ‘screen’ for the upper balcony (fig.3). In so doing, he avoided the potential pitfalls of relief,57 choosing not to hang a ‘stone poster’ on the outside of the building.58 In Read’s view the screen did not reveal a compromise or a sacrifice of sculptural ideals to architecture. Rather, it was a resolution of the dialectics of architecture and sculpture that had themselves emerged from the dissemblance of the monument.59 Time-Life Screen is neither ornament nor is it is a completely disconnected form – unlike Moore’s other sculptural commission for the Time-Life building, Draped Reclining Figure 1952–3, that, according to Moore’s biographer Roger Berthoud in 2003 ‘looks cramped on her balcony above Bond Street’.60 Time-Life Screen maintains its distinction as sculptural form by existing in space – viewable, if not in the round, then at least form two sides (Moore had hoped that each part of the screen would sit on revolving mounts),61 maintaining its sculptural integrity, but also being contiguous with the architecture of the building: ‘by actually piercing the screen so that light shows through it’, Read commented, ‘he even has avoided the effect of a second plane. The sculpture is suspended in the prime, architectural plane and thus is completely integrated’.62 The word integration is key: Read viewed Moore’s Screen as a perfect collaboration between architect and sculptor, and, particularly, of Moore’s sensitivity to context. Crucially, Moore compromised his ‘predominantly figurative work’ in his screen in favour of abstraction, which, for Read, was ‘evidence of his perfect understanding of the problem,’ presumably because figuration would have been at odds with the rectilinear design of the building.63 In what was, in Read’s opinion, Moore’s successful solution to the problem, he did more than produce a credible compromise for his sculpture: he re-synthesised the polarities of architecture and sculpture back into ‘that unity we call monument’.64

Henry Moore

Time-Life Screen 1952–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Errol Jackson

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Time-Life Screen 1952–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Errol Jackson

As the example of Time-Life Screen demonstrates, Read admired Moore for his ability to overcome the formal issues of a situation in order to effect a radical compromise that was, in fact, a new synthesis. It was his ability to synthesise from such polarities that made Moore’s position as participant to the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition and as contributor (as was Read) to Circle: International Survey of Constructive Art in 1937 not contradictory but reconciliatory. Although Read saw the classical/romantic duality as critically moribund and the abstract/surreal divide as resolved through the triumph of the surreal, he never saw resolution in the push and pull of Worringer’s abstraction and empathy. Within Moore’s work he perceived an ability to respond with the right measure of each, not as opposing tendencies, but as combining forces. In fact, following Worringer, Read began to see that the tension was not in abstraction versus (sur)realism, but within abstraction itself, the interplay of ‘vital and dead type[s] of abstraction.’65 The former, with its basis in the organic, pulls one in, whereas, for Worringer, quoted by Read, the abstraction of the Egyptian pyramid for example ‘calls a halt to our empathy impulse and presents itself to us as a purely crystalline, abstract construct.’66

Always in part a Freudian, if increasingly more sympathetic towards Jung, Read was not so foolish as to suppose that one could do away with the death drive, even if one’s whole practice was orientated towards Eros.67 In terms of Read’s understanding of modern sculpture, this polarisation was configured as the constructivist versus the organic, with Gabo representing, for Read, the former and Moore the latter. As Thistlewood has argued, organicism was the cornerstone of Read’s developing theory of aesthetics.68 However, this does not mean Read was dismissive of constructivism as an important part of modernism. It is telling that in the last collection of Read’s essays published in his lifetime, Art and Alienation, Moore and Gabo occupy the penultimate and final, chapters respectively.69 Although it would be unwise to put too much emphasis on Gabo having the last word, so to speak, the fact that Gabo’s ‘Platonism’ closes Read’s final text is not insignificant. Although Moore’s vital relationship to the world was always of greater appeal to Read the enduring romantic, Read never lost the sense that the artist, as much as the philosopher, aspired to a position beyond the contingencies of history. For example, Read may have dismissed pure abstraction as exemplified by Piet Mondrian’s later works as part deathly withdrawal, yet he admired Mondrian for his ‘heroic effort to escape from our subjective vision and from our determined position in time.’70 However, this metaphysical abstraction, heroic as it was, offered to Read nothing in terms of how to live now, whereas, Moore’s empathic, vital abstraction was fundamental to the awakening of a consciousness that was essential to Read’s desire for a new humanism.71

The individual and the group: Moore’s role in Read’s anarchism

If Read remained equivocal in his aesthetic sympathies throughout his life, within his politics, from the publication of Poetry and Anarchy in 1938 onwards, Read explicitly aligned himself with anarchism. In fact, he was adamant that he had never really wavered in his private belief in anarchy as the only viable form of radical politics.72 Professor of political studies, Dana Ward has called Read’s anarchism the ‘connecting tissue’ and ‘touchstone of his intellectual perspective’.73 Despite the fact that Read in Annals of Experience (1940) had claimed to have been influenced early on by poet, philosopher and activist Edward Carpenter’s Non-Governmental Society (1911) and political philosopher, anthropologist and zoologist Pyotr Kropotkin’s Fields, Factories and Workshops (1912), historian of British left-libertarian thought David Goodway has shown that Read’s political sympathies ranged from communism and social credit schemes to more Fabian forms of socialism and even a momentary support for totalitarianism as an ‘economic machine to facilitate the complex business of living in a community’.74 However, historical and personal events, notably the Spanish Civil War and his formative experience fighting in the trenches during the First World War – an experience that produced his second volume of poetry Naked Warriors (1919) – left him in no doubt that anarchism was the only ‘political doctrine which is consistent with our love of justice and our need for freedom’.75 Indeed, it was the Spanish Civil War that had caused Read to make public his commitment to anarchism. Although Read may have been unusual for his particular championing of anarchism, a position that he saw as being tantamount to political suicide,76 his position can be viewed as part of an inheritance of a strain of radical critical thought in England that reaches from John Ruskin and William Morris through to Roger Fry.77

The need for freedom, personal and political, was expressed more generally in Read’s work by an anti-authoritarianism and a distrust of dogma. Although always interested in pattern formation and principles of form, he was resistant to any attempt to impose pattern or programme on society. In the opening text of Poetry and Anarchism, simply titled ‘No Programme’, Read emphatically stated: ‘I speak of doctrine, but there is nothing I so instinctively avoid as a static system of ideas. I realise that form and pattern, and order are essential aspects of existence; but in themselves they are the attributes of death.’78

This death should be understood as metaphorical, in relation to abstraction as a withdrawal from the world, and as the creative death of the individual through repression. Nonetheless, this feared death was also very real, as revealed by Read’s concomitant commitment to pacifism, resulting from a dread of the violence that recent history had taught him was the consequence of programmatic politics and dogmatic belief. Thus, Read did not believe that anarchism was simply a utopian position, but the only viable political position for the survival of humanity.79 In 2006 Goodway argued that there was nothing particularly remarkable about Read’s particular brand of anarchism, being a fairly straight adoption of the central tenets of his main anarchistic teachers – Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Pyotr Kropotkin, Mikhail Bakunin and Edward Carpenter.80 However, as Dana Ward noted, Read’s path to anarchism was particularly influenced by his experience at the Leeds Art Club and, consequently, had a particular aesthetic dimension.81 At the centre of Read’s ‘aesthetic politics’ was the figure of the artist, as the individual in his or her fullest realisation. Read, across various texts, railed against the pressing into service of the artist by the state and the limitation of the artist’s freedom by either economic or political necessity.82 Given the increasing emphasis that Read placed on the importance of the artist’ s individuality being allowed to develop unencumbered, it would be fair to assume that Read was aligned with an ego-philosophy like that of the German philosopher Max Stirner, author of The Ego and its Own (1845). Indeed, in his final essay explicitly on the subject of anarchism, Read expressed his admiration for Stirner, believing that the importance of his insights had been unfairly overlooked.83 In fact, Read, at the outset of his writings on anarchy, made no claims for providing a politics that was of benefit to society, but rather saw his anarchism as part of his own self-actualisation, declaring that ‘I shall endeavour to live as an individual; to develop my individuality’.84 However, this would be to over-simplify the complexity of Read’s position. Read was only concerned with the individual as a part of a community and only concerned with a community as it provided the best environment for the individual. Hence, Read asserted that the ‘question of the relation of the individual to the collective society of which he is a member is the fundamental issue, in art as well as politics.’85 For Read, the artist was an ideal individual, not because he/she struggled against society and pursued his/her ego at the expense of the community, but because in striving for a freedom in his/her work, the artist became the ideal member of the community. If, in his break with academicism and dogma, Moore was the embodiment of the ideal individual artist, Read was at pains to make clear that the manner in which he exercised this freedom was of value beyond a mere expression of personal development. Amplifying this view, Read quoted Jung, referring to ‘the artist in a higher sense “man”, he is the collective man, the shaper of the unconsciously active soul of mankind.’86 It was Moore’s ability to be both an individual and ‘collective man’, that made his work so central to the development of Read’s ‘aesthetic politics.’

Moore’s own choice of political radicalism may have been communism and forms of socialism,87 but he shared Read’s view on the artist as essentially an individual whose creative freedom was the pre-condition for significant and meaningful art. Speaking to Unesco in 1953, Moore echoed Read’s fear of the impingement on artistic development of external control, declaring, ‘the evolution of art cannot be forced, nor can it be retarded by an obstinate adherence to outworn conventions.’88 However, it was not primarily Moore’s expounding of an artistic freedom, a freedom most particularly championed by American cultural diplomacy after the war, that made him crucial to Read’s anarchistic politics. Rather, it was Read’s understanding of Moore’s work as exemplary of a relationship between the one and the many, the particular and the universal that made him the ideal artist of the anarchistic impulse.

Read was aware of the potential contradiction between the pursuit of extreme individuality and the desire for community at the heart of his anarchistic philosophy. His anarchy was not that of the poet, critic and educationalist Matthew Arnold’s feared mob rule,89 positioned in opposition to the ordering effects of culture, but was based on a belief in the integral order of life. With the abandonment of imposed order from all forms of government and religious and political dogma, he asked from where an understanding of order should arise. His answer was Nature.90 In part this answer was due to Read’s self-professed pastoralism. Read made no secret of the fact that he considered the industrialised urban world to be a denigration of humanity, the focus of his attack being all forms of technocracy.91 In 1949 Read returned to his native Yorkshire to live in Georgian rectory called Stonegrave with seven acres of land in a long-desired move that was to prove, in James King’s words, ‘a symbolic act of renewal.’92 This return to the rural idyll of his youth was reflected in some of his final writing where he declared that even his support for industrial design had only been because he had hoped that in supporting such advanced production society would move through this phase of mechanisation and return to the land, albeit with better technology, so that the life of the peasant was no longer of toil, but of leisure. Read was, of course, not the first anarchist to come from the land rather than the city: Bakunin had a peasant background (Read also proclaimed himself to be, at times, a peasant)93 and Kropotkin’s anarchy had been influenced by his experience of non-urban life both as part of a landed gentry and in his travels to visit rural communities. It is, therefore, unsurprising that Read, in his biographical prelude to Moore’s work, stressed the significance of Moore’s early life ‘on the border of town and country’ and his connection to the very material of the land through the local industries of mining and pottery.94 However, Read also rejected any form of nostalgia for a former way of life, and so scorned the ‘sentimental reaction’ of the nineteenth-century designer and activist William Morris.95

Accordingly, although Read was drawn to Moore in part because of his background, seeing parallels with his own, he did not see Moore as a rural throwback. A vital connection with nature did not mean, for Read, a romantic nostalgia, but a kind of empiricism. In this vein, he disputed the categorisation of the painter John Constable as a romantic, stating that ‘his preparatory ‘sketches’ are no more romantic that a weather report.’96 Similarly, Moore, as empiricist and intuitive investigator of a quasi-scientific truth, did not produce romantic renditions of the natural world, but, rather, demonstrated a rigorously acquired knowledge of nature, that Moore termed ‘form-knowledge’.97 It was Barbara Hepworth who helped Read understand that the abstract artist did not work in opposition to nature but constantly returned to deep observation of the natural world in order to rejuvenate his or her creativity.98 Like Hepworth, Moore periodically returned to life-drawing and naturalistic studies in order to reconnect with observed reality but it was his constant engagement with the structures and materials of the natural world that made him exemplary of an empirical method that, for Read, was the essence of a vital abstraction. Indeed, even the abstractions of Moore’s Time-life Screen were developed from studies of shell and bone forms that Moore had collected.99 As Read had observed in 1931, Moore did not attempt to represent such forms but to translate their vital qualities and, in so doing, discover the relationship between the material form of the original object and the properties of the receiving material: the inherent properties of growth and form.

The culmination of Read’s interest in organic unity occurred in 1951 with his involvement in the Aspects of Form symposium at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), London. Read, in his preface, for the subsequent publication declared:

But now the revelation that perception itself is essentially a pattern-seeking and pattern-making function (a Gestalt formation); that pattern is inherent in the physical structure of the functioning of the nervous system; that matter itself analyses into coherent patterns or arrangements or molecules; and the gradual realisation that all these patterns are effective and ontologically significant by virtue of an organisation of their parts which can only be characterised as aesthetic – all this development has brought works of art and natural phenomena on to an identical plane of enquiry. Aesthetics is no longer an isolated science of beauty; science can no longer neglect aesthetic factors.100

It was this view of the natural world as a place of order, structure and harmony uncovered through scientific and artistic methods of enquiry that was central to Read’s politics. For Read, society was an organism, like any other, that would develop under its own principles of growth and form if left free from governmental control.101 Here Read was following in the footsteps of one of his anarchist teachers, Pyotr Kropotkin, whose book Mutual Aid (1902) was a challenge to those who had taken Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and used it to suggest a dominating logic of competition and self-interest. Built on his own work studying people and animals living in different habitats and formations, Mutual Aid defended what Kropotkin saw as the vital need for cooperation between individuals within a society, but also the need to ground politics in scientific knowledge.102 It was this anarchist inheritance of politics, which was rooted in evolutionary biology, that connected Read’s interest in theories of Gestalt psychology and modern biology to his political philosophy.103 Most crucial for an understanding of the significance of the relationship between Moore’s investigations into natural form and Read’s philosophy104 was the idea of the developing organism as understood through the work of D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s book On Growth Form (1917), the inspiration behind 1951 ICA exhibition that had given impetus to the symposium.105 Whilst he never defined the relationship between biological principles of organic development and anarchy, it is easy to see how Read’s interest in the freely developing organism, with its harmony and structure unto itself (not imposed), was important to a political philosophy that insisted that society should develop ontogenetically.106 The role of the artist was to exercise the natural pattern-seeking tendencies of the nervous system to communicate this underlying organic order.107

There was, however, an equivocation within Read’s persistent characterisation of Moore’s work as organic and a concomitant uncertainty about how the artwork might serve as the basis for the instantiation of natural law and, in turn, anarchy. Was Moore’s work ideally organic and vital because it represented natural form or because it developed, as Worringer had said was true of all works of art, as an organism itself, or, in Read’s words, ‘an organic event, unfolding as naturally as the petals of the wild rose’?108 Read, and other critics, were anxious to avoid the location of Moore’s organicism in his representation of formal characteristics, fearing a literalism that would leave Moore’s work as merely academic and illustrative and, for Read, unacceptably predetermined and determining.109 However, if it was the developmental process that made a work exemplary of an organic vitality, not its appearance, then why should Moore’s work, more say than Hepworth’s or Gabo’s, be exemplary?110 Despite Read’s great interest in Moore’s process, it appears that, for him, it was Moore’s ‘recognizably organic shape[s]’ that made his work the epitome of vital organicism.111 In fact, Read believed that what made a work of art valid was exactly its departure from universal principles of harmony.112 Moore’s work was illustrative for an anarchist society, not because of its organic unity, but because it made manifest the compromise between underlying structures and individual volition.

Perhaps it is revealing of an uncertainty concerning the manifestation of the organic in Moore’s work that, in his final essay written on the sculptor, Read focused on another area of vitality that he felt was crucial to the significance of art for society at large: the artist’s ability to uncover forms from the collective unconscious. Jung’s notion provided an answer to many of Read’s apparently irresolvable questions. How could the pursuit of complete individuality, as embodied by the artist’s creative freedom, be at the same time a move towards the community? Why was abstraction from nature, intuition and ‘primitive art’ of greater significance than an academic practice, mimesis, representation or ‘pure’ abstraction? The revelation of the collective unconscious, through the manifestation of archetypes, also gave Moore his ultimate place at the centre of Read’s conceptual universe.

In ‘The Reconciling Archetype’ Read cast Moore as an artist who transcended the personal to produce forms that appeared, in Jung’s words:

‘as if [they] had emerged from the abyss of the pre-human ages, or from a super-human world of contrasting light and darkness.’ He had ‘plunged into the healing and redeeming depths of the collective psyche where man is not lost in the isolation of consciousness and its errors and sufferings, but where all men are caught in a common rhythm which allows the individual to communicate his feelings and strivings to mankind as a whole.’113

Read saw a synergy between Jung’s statement and Moore’s own explication of his work:

Because a work does not aim at reproducing natural appearances it is not, therefore, an escape from life – but may be a penetration into reality, not a sedative or drug, not just the exercise of good taste, the provision of pleasant shapes and colours in a pleasing combination, not a decoration of life, but an expression of the significance of life, a stimulation to a greater effort of living.114

Read linked Moore’s statement back to what would be the final dialectical pairing of his career: ‘the whole philosophy of art implicit in the statement depends on a fundamental distinction between beauty and vitality as the “function” of art.’115 In some ways this was just a restatement of Worringer’s abstraction and empathy. However, Read took a new twist on the old theme. Rather than seeing beauty as a detachment from the world in opposition to Moore’s life-affirming engagement, Read characterised Moore as a ‘tragic’ artist who ‘never sought to idealise the human body, to make it the ideal representation of beauty, a stimulus to sensuous enjoyment.’ It was not that Moore’s work was now against life, but that, with the ghostly presence of Read’s early Christian teachings intermingling with his later existentialist sympathies, the revelation of the tragic nature of human existence became in itself a redemptive force. It was, Read emphasised through a reiteration of Moore’s words, ‘”an expression of the significance of life, a stimulation to greater effort of living”.’116

It is with this explication of the ethics of his work as an incitement to a better, more responsible way of living that Moore took on the role of redeemer within Read’s aesthetic politics. Moore’s art had, then, an essentially religious quality for Read, due to Moore’s ability to relate between the ‘pathetic and the symbolic, between the particular and the universal’, as shown, for example, in his exploration of the particularity of the mother and child theme in relation to the universally symbolic form of the Madonna and Child, carved in 1943–4, in his St Matthew’s church commission.117 But the very significance of the religious theme is only possible because of the pre-existence of the archetype: ‘an inherited tendency of the human mind to form representations of mythological motifs – representations that vary a great deal without losing their basic pattern.’ Tendencies that are fundamentally related to evolution and biology: ‘this inherited tendency is instinctive, like the specific impulse of nest-building, migration, etc., in birds.’118

It is through Jung’s theorisation of the archetype, as applied to Moore’s work, that Read is able to bring together his belief in the need for art to replace religion and the artist as ideal individual orientated towards the community, with theories of evolution and biology as the scientific basis of aesthetics and politics. However, aware that the idea of ‘chief’ types was potentially inimical to a notion of a politics without ‘chiefs’, Read was careful to assert the virtual nature of the archetype as a predisposition, a potentiality, always updating and developing. Consequently, the role of the artist was to avoid the re-presentation of archetypes already extant within culture as de-vitalised and academic clichés and instead to re-vivify the symbolic by, in Jung’s words, ‘fiercely making use of every precondition’.119 Moore’s main themes – the mother and child and the reclining figure – were not simply pre-existing forms channelled by the artist as medium, but were concrete manifestations of the artist’s engagement with all of history and experience as it was present in a particular moment and actualised through the artist’s imagination as exemplars of redemptive freedom. Read explained: ‘The forms of art are only significant in so far as they are archetypal, and in that sense pre-determined, and only vital in so far as they are transformed by the sensibility of the artist and in that sense free.’120 It was in their vitality that Moore’s ‘archetypes’ became reconciliatory because they represented the move from observation of the particular towards and connection with the universal, which for Read, quoting Goethe, is the ‘nature of poetry, of all great art.’121

Once again Read used Moore as exemplar, rather than critical material. Although, as Read acknowledged, a deep enquiry into Moore’s particular relationship with key archetypes was not necessary as this had already been undertaken by Erich Neumann, it is significant that, whereas Neumann wrestled with the way in which Moore’s work might be said to have related to the zeitgeist of his age, or the ‘collective Weltanschuanng’,122 Read simply took it as given that it did. The point is that Moore was not just an artist whose work interested Read, but was, rather, the cornerstone of Read’s understanding of the possibility of the relationship between the individual and the group and the particular and the universal.

The unreconciled image

Moore occupied an explicit role within Read’s aesthetics, at its centre, reconciling and synthesising the unacceptable critical dualism whereby ‘in the classical artist the form is so important that the subject-matter is almost irrelevant; whilst in the romantic artist the subject-matter is so important that it completely overwhelms the form’.123 This position of credible compromise was vital to Read in as much as it provided a model for this wider aesthetic-political philosophy. However, there is much in Moore’s work that remained unassimilated by Read’s aesthetic politics. Perhaps there is another way of conceiving of the Moore/Read dynamic which, though no less revealing, is detectable only through its explicit absence. This speculative dynamic is, accordingly, most fruitfully found in the area of Moore’s practice with which Read had the least engagement, namely his drawing. As art historian Andrew Causey showed in 2010, Moore’s drawings operated distinctly from his sculptures, not necessarily being sketches for sculptures that Moore made (although some were), but rather developing a surreal world in which his sculptural forms become spectres occupying their own landscapes and creating their own visual language.124 If Moore’s sculpture stands out in its claims for universality and singularity, then his drawing represents the contingency and contemporaneity of his work. Although Read was one of the first to address Moore’s drawings,125 and devoted a chapter to them in his book on Moore, apart from the ‘shelter’ series, there is no sense that Read saw Moore’s drawings as anything but preparation for his sculpture. Neumann, in contrast, devoted attention to the drawings as a distinct and unsettling part of Moore’s practice. Writing about Figures in a Setting 1948, part of a series of drawings of figurative and non-figurative sculptural forms in internal spaces, he commented:

The haunted bleakness of Moore’s prisonlike rooms is certainly no less enigmatic that Chirico’s endless streets and squares ... One feels that the window slits are pointers to some powerful and incomprehensible reality in the background, which, as in the works of Kafka, has its own horizon far beyond the stage reality of this prison world, and an amplitude that remains forever inaccessible to human consciousness.126

Neumann’s reading of Moore’s drawings would fit well with an understanding of them as part of a surrealist interest in the unconscious (collective and individual), a view that the critic Robert Melville supported in the 1953 exhibition he instigated of Moore’s drawings at the ICA.127 However, there is perhaps a less psychoanalytic way of seeing these casts of figures expressionlessly inhabiting their stark modern environments that is suggested by the title of Melville’s essay for the 1953 exhibition, ‘Communities of Statuary’.128 Just as Moore’s work, with its placing in front of buildings, private and public and in sculpture parks across the world, became a part of the imagining of a public of a desired post-war consensus, experiencing an art that was paid for by them and, supposedly, for them, these drawings seem to speak, prophetically, to the ambivalence of such a notion of a public: its promise as community and its threat as ‘mass’. Whilst commissions, such as those of Time-Life, St Matthews or Unesco, revealed Moore to be a supremely sensitive interpreter of context (even if that meant resisting the allegorical associations with context)129, in his drawings Moore seemed to question the possibility of a public that his work might participate in creating. From the interiors of the 1930s, to the shelter and miner pieces of the 1940s, Moore’s drawings occupy a space of ambiguity – a profound uncertainty about the relationship between individual and group, the humanity and inhumanity of the collective that exceeds Read’s notion of an archetypal connectivity, but represents the ambivalence of some of his anarchistic writings.130 As Moore’s figures stand surveying each other as the objects and subjects of the blank interiors and landscapes of post-apocalypse or modern design, a great, repressed, contradiction at the heart of Read’s engagement with Moore’s work becomes apparent; the art Read saw as full of anarchist potential, was, in fact, the favoured art of a state capitalism that Read despised.131

Read devoted himself a number of times to the question of patronage and grew increasingly doubtful that any form of centralised, state patronage could produce art of value:

In the past fifty years vast sums have been expended on the purchase not only of ‘old masters’ but also of contemporary works of art of all schools, and equally large sums have been spent on the building of museums, theatres, opera houses, concert halls, etc., and on the subsidy of performances in such institutions. All to no effect on the basic problem, which is the creation of a vital democratic art to correspond to our democratic civilisation. Our civilisation in its visual aspects, is chaotic; it is without a characteristic poetry, without a typical drama: its painting and sculpture have now sunk to a level of mindless incoherence whilst its architecture is reduced to an ‘economic’ functionalism that projects its own ‘brutalism’ as an aesthetic virtue.132

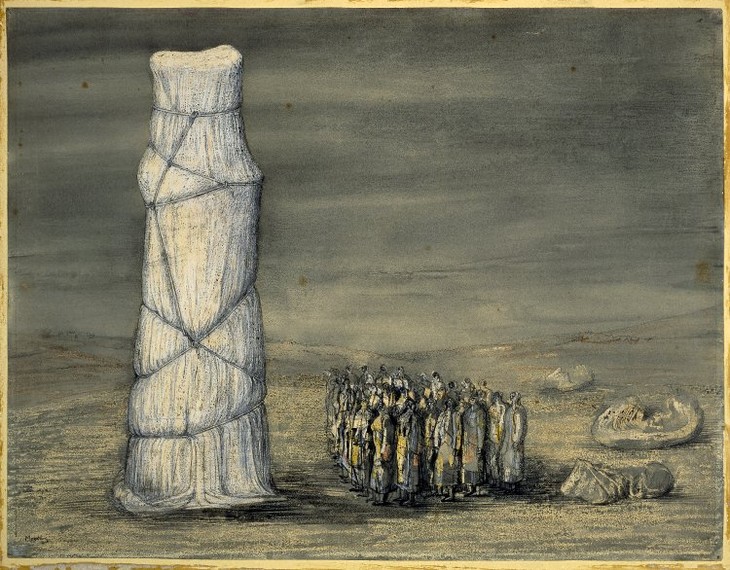

It is strange that Read could bemoan public patronage for failing to produce a vital democratic art, and yet fail to reflect on how Moore’s work fitted into this political-economic context. It was not that Read was unable to see Moore’s work as connected to contemporary society, but that Moore’s greatness, for Read, resided in his constant ability to transcend the particularities of his time. Even a piece so directly related to contemporary history as Atom Piece 1964 (subsequently retitled Nuclear Energy) Read managed to relate to Thompson’s ideas of growth and form and the ancient paradox of inherent beauty in the ‘shapes associated with evil or murderous purpose – the shapes of spears, axes, swords.’133 In one of Moore’s most affecting drawings, Crowd Looking up at a Tied-Up Object 1942 (fig.4), the crowd face not another figure, but a monumental monolith wrapped in cloth and tied. Again, it is not clear if the group stand in hope, fear, anticipation or judgement of what is about to be revealed. This image, reproduced by Read in his biography of Moore, sits almost at the centre of the book and yet incites no commentary from Read. Instead, it symbolically stands for that which Read disavowed within his work: the failure of the modernist movement (and monument) to produce a community of individuals, and its successful instrumentalisation by patrons, public and private alike.134 While placing Moore within Read’s wider politics may unlock an anarchic possibility of becoming in his sculptures, Moore’s drawings revealed the blind-spot at the centre of Read’s critical life: his own position as a functionary of Keynesian cultural paternalism.

Henry Moore

Crowd Looking at a Tied-Up Object 1942

© Trustees of the British Museum; © The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Crowd Looking at a Tied-Up Object 1942

© Trustees of the British Museum; © The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Read and Moore: a mediated and dynamic relationship

In 1957 the critic and curator Lawrence Alloway wrote a ‘Personal Statement’. In it he dismissed the art critics of his youth, namely Bernard Berenson, Herbert Read and Roger Fry, who, in his opinion, had given him, ‘no guidance on how to read, how to see, the mass media.’135 Alloway was correct that Read had not provided a place for the development of new media forms, from film and television, to radio and advertising, within his aesthetic philosophy. This oversight was especially striking when it came to photography. One of Read’s greatest contributions as author, publisher and editor was to reproduce an extraordinary array of images in high-quality reproduction. Indeed, at the beginning of Art and Industry (a book that is a veritable cabinet of curiosities of images), Read noted the great importance of paying for a ‘competent artist’ to photograph industrial design to give it the ‘same chance as a work of fine art’.136 The very premise of Art and Industry is that industrial design, art and craft should be understood as part a continuum, with one end the more symbolic and the other more functional, but each part equally capable of significant form.137 With similar tacit acknowledgement of the art of photography, in his preface to his 1965 work on Moore, Read commented that Moore was ‘the best photographer of his sculpture.’138 For Moore and Read, however, it seems that photography was no more than a tool with which to see better the essential qualities of sculpture:139 there was no sense that photography, as one of the primary ways in which Moore’s work was mediated and experienced, might itself be in need of consideration. Equally important was the role of photography and print media in giving Moore access to a variety of sculptural practices from across the globe, beyond what was represented in the museums that Moore frequented.140

The failure to consider the role of photography in the production of modern art was especially peculiar given Read’s involvement in the development of the ICA, whose early exhibitions played with the possibilities of photographic reproduction.141 The fact was that Read’s interest in Moore’s practice was particularly aligned with his commitment to sculpture as an art form of palpable presence. As art historian David Getsy argued in 2011, Read’s particular use of Moore was to create a theory of sculpture based on its tactile, rather than optical, qualities, in direct refutation of Clement Greenberg’s developing theories of optical primacy.142 Getsy, however, was careful to explain that Read’s idea of tactility in relation to sculpture should not be taken too literally and that what he was highlighting was, rather, the multi-sensory nature of experience.143 Getsy was right to see Read’s sculptural theory as not as naïve as Greenberg’s characterisation of it would suggest. However, Read’s particular promotion of the handling and ‘fondling’ of objects should also not be dismissed.144 Both Moore and Read were to describe the value of actually handling objects in the museum to gain a full understanding of them.145 The particular value of sculpture, both for artist and audience, was as a medium that encouraged a literal reaching out and touching – an important experience for ‘the alienated person’ of modern industrial society, who is ‘out of touch with himself as he is out of touch with any other person.’146 Sculpture, through its promise of tactility, was, for Read, the medium best suited to put people back in touch with each other and with the world. If ‘fondling’ seemed a strange verb to use in relation to art appreciation, it accorded perfectly with Read’s desire to ‘redefine humanism in the terms of a sensuous apprehension of being.’147

Read’s oversight of the importance of new media and his commitment to an ‘aesthetic’ distance built on a universalism frequently built around essentialising languages of race, nature and the primitive,148 may have kept him stuck on the ‘wrong’ side of the modernist fence for future generations of artists and writers, with Moore equally mired by the quasi-mystical language of archetypes and vitalism.149 However, Read’s appreciation of Moore’s work as the record of a process of encounter between idea and material, with the ‘spectator’s’ ‘tactile’, ‘haptic’, ‘somatic’ and dynamic interaction with the work being the instigation of another creative process of embodied apprehension and action,150 suggests a much more radical relationship that may be of enduring relevance to contemporary art and political action.151 Read was as interested by the creative process as he was by the final artistic form and believed that modern science,152 especially Einstein’s theory of relativity, proved that ‘subject and object were one.’ Quoting Karl Jaspers, Read asserted ‘let us ... agree, that “since there is no complete truth, our movement toward it is itself the only form in which truth can achieve completion in existence here and now.”’153 Such an assertion of the durational and relational nature of truth chimed with Read’s increasing interest in the philosophy of A.N. Whitehead and his theory of the event,154 but it was to the artist Paul Klee who Read turned for the clearest formulation of creativity as an on-going process: ‘All becoming, as Paul Klee says, is based on movement, and I shall take Klee’s Creative Credo, which he wrote in 1920, as the best description known to me. The scene of action he says, is time. The one and only character: movement.’155 This relates to what Read referred to in his first review of Moore as his ‘four dimensional process’,156 an unfolding event at the centre of myriad forces. Truth, as opposed to beauty, even the concrete truth of Moore’s sculptures, was the process of becoming, not the end result. This philosophy was reflected in Read’s personal version of anarchy, which was pragmatic rather than idealist, starting in the ‘midst’ of things,157 but also speculative, in that its desire was always revolutionary. Consequently, the artist as one who, in Jung’s words, ‘freely make[s] use of every precondition’,158 is identical with the anarchist, as one who does not pursue a utopian dream, but whose aim is ‘neither to believe, nor suffer, nor renounce, but to accept, to enjoy, to realise the anarchy of life in the midst of the order of things.’159 The wonder of Moore for Read, was not his idealism, but his ability to operate a ‘speculative volition’160 from within the midst of things to produce some ‘grains of the real’161 in a world out of touch with itself. In his explanation of Moore’s art as a constant process of engaging in the preconditions of the world and in the production of something distinct (what the social theorist Brian Massumi might call the ‘relational’ and ‘qualitative’ dimensions of the event),162 it should be clear that Read was describing his own critical process. The balance that Read desired at the centre of his aesthetic axis, a balance that he believed Moore achieved, was not mediocrity or compromise but a ‘dynamic equilibrium’163, ‘the very delicacy and subtlety’ of which, ‘is of its essence, for joy is only promised to those who strive to achieve it, and who, having achieved it, hold it lightly poised.’164

Notes

Ibid, p.30–6. For a discussion of the Leeds Art Club and the other significant fora of Read’s career, see Nanette Aldred, ‘Herbert Read and the Flow of Ideas: From the Leeds Arts Club to the ICA’, in Michael Paraskos (ed.), Re-Reading Read, London 2007, pp.76–87.

For a full explication of the complexity of influences on Read’s aesthetics and philosophy see, David Thistlewood, Herbert Read, Formless and Form: An Introduction to His Aesthetics, London, Boston, Melbourne and Henley 1984.

Michael Paraskos, ‘Introduction’, in Herbert Read, To Hell with Culture, Abingdon and New York 2002, p.x.

Two important collections of essays have been published in the least twenty years that have significantly redressed this neglect: David Goodway (ed.), Herbert Read Re-Assessed, Liverpool 1998, and Michael Paraskos (ed.), Re-Reading Read, London 2007.

Henry Moore was also part of the presentation, but was seen by Read in contrast to the younger sculptors as the ‘parent’ of the group. For a full discussion of the context of Read’s famous phrase see Margaret Garlake, ‘Revisiting the Geometry of Fear’, in Paraskos 2007, pp.134–43.

It is interesting to note that just as the unity of Moore’s work appealed to Read, it was the emergence of the ‘intensely restless’ in Moore’s work that appealed to another key critical supporter, David Sylvester. Indeed, Sylvester was at times unsure of Moore’s importance as a contemporary artist favouring the more angst-ridden work of Giacometti. See Martin Hammer, ‘Ambivalence and Ambiguity: David Sylvester on Henry Moore’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, 2015, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/martin-hammer-ambivalence-and-ambiguity-david-sylvester-on-henry-moore-r1151307 , accessed 10 September 2015.

It is the work and writings of the artists, architects and critics who made up the group, latterly termed the Independent Group (IG), that most clearly marks the shift in thinking that made a break with Read’s position. For an account of the IG that makes evident the way in which generational rupture was crucial to their formation and demonstrates how Read became a symbolic focus for this rupture, see David Robbins (ed.), The Independent Group: Postwar Britain and the Aesthetics of Plenty, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London 1990.

For an account of the IG that provides a more nuanced assessment of their connection with the founding generation of the Institute of Contemporary Arts, see Anne Massey, The Independent Group: Modernism and Mass Culture 1945–59, Manchester and New York 1995.

Chris Stephens, ‘Anything but Gentle: Henry Moore – Modern Sculpture, in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, p.14.

The term ‘aesthetic politics’ was coined by Howard Zinn in his introduction to the 1974 edition of Read’s Anarchy and Order. However, I am using it as developed by Dana Ward, ‘Art and Anarchy: Herbert Read’s Aesthetic Politics,’ in Paraskos 2007, pp.20–33.

Herbert Read, The Forms of Things Unknown: Essays Towards an Aesthetic Philosophy, London 1960, pp.65–70.

Read was involved in Moore’s choice to produce drawings of miners for the Artists War Commission and felt he had aided Moore’s development as a writer on his own work (he notably claimed to have helped the artist write his important statement about his sculptural values for the Unit One catalogue that Read edited, though possibly his role may not have been as decisive as he recalled. See Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.8.

Roger Fry’s review of Eric Gill’s work in 1911 is remarkably similar to Read’s 1931 review of Moore in its support of Gill’s sculptures as ‘positive creations ... the outcome of the desire to express something felt in the adventure of human life’, rather than being ‘more or less successful copies of that desperately unreal and fictitious thing, the model posing in the studio’. Roger Fry, ‘An English Sculptor’, Nation, 28 January 1911, pp.718–19, reprinted in Christopher Read (ed.), A Roger Fry Reader, Chicago and London 1996, pp.133–5.

Read was not the only critic to value sculpture as an art of carving and to see Moore as the torch bearer of such technique. Notably Adrian Stokes was, as Richard Read comments, ‘the great advocate of direct carving’. See Richard Read, ‘Circling Each Other: Henry Moore and Adrian Stokes’ in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, 2015, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/richard-read-circling-each-other-henry-moore-and-adrian-stokes-r1151308 , accessed 10 September 2015.

Goethe was an important reference point for Read’s philosophy, underpinning his understanding of the relationship between organic form and the artwork (see Thistlewood 1984, p.132), while James’s experimental psychology appealed to Read’s desire to ground experience in scientific method. Both James and Goethe take these respective roles within Read’s essay ‘The Creative Process’, in Read 1960, pp.49–63.

Nietzsche was an early influence on Read and, although not so explicitly referenced in later work, remains important to Read’s ideas of individual freedom and the enduring value of aristocracy, not as the rule of a particular social group, but as an ‘aristocracy of the intellect’. See Herbert Read, Anarchy and Order, London 1954, p.103.

Herbert Read, ‘The Faculty of Abstraction’, in Ben Nicholson, Naum Gabo and John Leslie Martin (eds.), Circle: International Survey of Constructivist Art, London 1937, p.66.

Read’s Philosophy of Art is dedicated to Worringer as ‘my esteemed master in the philosophy of art’.

Read articulated Hulme’s reading of Worringer at the outset of his essay on Ben Nicholson, rather than Moore, because his work represented an oscillation between the different ends of the polarity: Read, The Philosophy of Art, 1954, p.220.

Worringer’s relativism is reflected in his assertion that, ‘every style represented the maximum bestowal of happiness for the humanity that created it’. Consequently, ‘all valuations made from our standpoint, from a point of view of our modern aesthetics, which passes judgement exclusively in the sense of the Antique or the Renaissance, are from a higher standpoint absurdities and platitudes’. Wilhelm Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, trans. by Michael Bullock, London and New York 1910, p.13.

Anton Ehrenzweig, ‘The Unconscious Meaning of Primitive and Modern Art’, talk given at the ICA, September 1949, Tate Archive TGA 955/1/7/12.

Read, The Philosophy of Art, 1954, p.220. Thistlewood connects Worringer’s abstraction and empathy to Read’s understanding of Moore’s work as humanist. See Thistlewood 1984, p.166.

Moore frequently maintained that he did not believe that one had to be completely surreal or abstract, preferring the melding of the two. See Wilkinson 2002, pp.112–13.

Herbert Read, The Art of Sculpture, London 1956. Moore was narrowly beaten into second place by Michelangelo reproductions in the book.

Moore in Wilkinson 2002, p.252–3; Moore discusses the problem of relief in relation to his commission for the London Underground Headquarters, West Wind 1928–9. It should also be noted that Read and Moore’s shared concerns about the art of relief stood in marked contrast to the position of critic Adrian Stokes who came to its defence. Stokes, although a supporter of Moore’s work, advocated for the pictorial within sculpture, which was at odds with Moore and Read’s commitment to sculpture as a non-pictorial art of three dimensionality. See, Richard Read, ‘Circling Each Other: Henry Moore and Adrian Stokes’, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/richard-read-circling-each-other-henry-moore-and-adrian-stokes-r1151308 , accessed 10 September 2015.

Read asserted the persistent relevance of Freud’s death drive for the tragic element in Moore’s sculpture in his final essay on Moore, ‘The Reconciling Archetype’, in Art and Alienation, New York 1967, p.127.

See David Thistlewood, ‘Herbert Read’s Organic Aesthetics: 1918–1950’ and ‘Herbert Read’s Organic Aesthetics 1950–1968’, in Goodway 1998, pp.215–47.

David Goodway, ‘The Politics of Herbert Read,’ in Goodway 1998, pp.177–95. Goodway actually tempers Read’s claim for consistency against the complex changing nature of Read’s early political sympathies.

David Goodway, Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow: Left Libertarian Thought and British Writers from William Morris to Colin Ward, Liverpool 2006, pp.175–8

See Donald D. Egbert, ‘English Art Critics and Modern Social Radicalism’, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol.26, no.1, Autumn 1967, pp.29–46.

This was to be an enduring theme for Read but began to be a particular concern with the news of the suicide of the Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky; see Read 1941, p.21.

Herbert Read, ‘My Anarchism’, in Anarchy and Order, London 1974 (the essay only appears in this later edition), pp.230–47, pp.238–39.

Henry Moore, ‘The Sculptor in Modern Society’, reprinted in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (eds.), Art in Theory, 1900–2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Oxford 2003, p.679.

Matthew Arnold, Culture and Anarchy 1869, London 1932, pp.76–7; ‘his right to march where he likes, meet where he likes, enter where he likes, hoot as he likes, threaten as he likes, smash as he likes. All this, I say, tends to anarchy’.

Herbert Read, Anarchy and Order: Essays in Politics, London 1954, p.41. See also Thistlewood 1984, p.73.

See Jennifer Mundy, ‘Comment on England,’ in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, p.28.

Herbert Read, ‘Preface’, in Lancelot Law Whyte (ed.), Aspects of Form: A Symposium on Form in Nature and Art, London 1951.

Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, edited with an introduction by Paul Avrich, London 1972, pp.17–23.

Read, 1965, p.113; Henri Focillion was also an important influence on Read’s understanding of the relationship between ‘natural’ and ‘artistic’ form.

This position was put forward by Rudolph Arnheim at the Aspects of Form symposium, Rudolph Arnheim ‘Gestalt Psychology and Artistic Form’, in Whyte 1951, pp.196–208.