How does one construct the history of exhibitions – forgotten, unwritten, disparate, often lacking in documentation? In what ways might it be a new kind of history, displacing the traditional focus on objects and related critical histories, yet irreducible to the term ‘museum studies’? In what ways have exhibitions, more than simple displays and configurations of objects, helped change ideas about art, intersecting at particular junctions with technical innovations, discursive shifts and larger kinds of philosophical investigations, thus forming part of these larger histories? What does it mean to ask such questions in the era of fast-moving celebrity curators, biennials and fairs, digital ways and means, which have taken shape over the last twenty years?

In this context, it is instructive to look back to Paris in 1985, to an exhibition entitled Les Immatériaux, then the largest to date at the Centre Georges Pompidou, conceived as a dramaturgy of information for the post-modern condition by its curator, the philosopher Jean-François Lyotard. Documentation of this exhibition is now hard to come by; and even though I have held onto the catalogues and related materials from the press-kit for the review I wrote at the time, it still seems difficult to bring into focus what I saw then.1 In what follows, I offer some afterthoughts based on my presentation at the Landmark Exhibitions conference at Tate Modern which form a sketch, a history of exhibitions yet to be written, a little fable in which Les Immatériaux figures as a turning-point.2 The aim of this text is to encourage others to look back at the still striking or strange objects and concerns of this exhibition, which was at once intense and disappointing for Lyotard at the time.

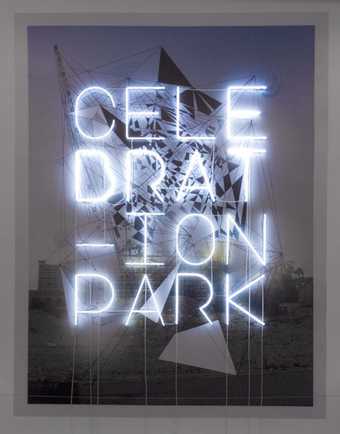

Fig.1

‘Tous les auteurs’ site, the exhibition’s concluding area, where the visitor could participate in real time in various digital writing experiments

Photograph © CCI/J.- C. Plancher, 1985, scenography by Philippe Délis

No doubt there are many great precursors – artists as well as curators – for the sort of unwritten history of exhibitions I have in mind. In this history, artists and artist-groups matter as much as established institutions; it is often from the former that new ideas arise, and from them that curators draw inspiration. One thinks of Alexander Dorner for example, whom – along with El Lissitzky and Kurt Schwitters – Benjamin Buchloh credits with initiating a shift from ‘objects’ to ‘spaces’ (and hence from ‘spectators’ to ‘participants’), a shift later touted as a new idea of art. Dorner’s ‘laboratory’ intersected with pragmatism and a world of things in the making, relating ideas of ‘experimentalism’ in art and in thought, much as Aby Warburg’s archival project – which is so appealing to contemporary curators – now resonates with questions about time and image.3

However, Les Immatériaux has the distinction not simply of intersecting with philosophical questions, but actually of being the work of a philosopher, arguably even a work of philosophy, even if it was not recognised as such at the time. We may think of Les Immatériaux as a move from philosophy to exhibition, which formed part of Lyotard’s ongoing attempt to recast the discipline Kant called ‘aesthetics’ in a period after the Second World War that had seen the displacement of Dorner and Warburg’s archive into English-speaking cultures. Les Immatériaux thus belongs to another history, one that also needs to be written, of the peculiar relations exhibitions have had (and might yet have) with, and in, the great transformations in the discipline of aesthetics – a philosophical discipline that has overdetermined or overshadowed the preoccupations of art history or art criticism since the nineteenth century. An elaborate commentary on the fate of the ‘sublime’ in the idea of ‘aesthetics’ or a constant turning back to Theodor Adorno’s ‘melancholy science’, would accompany Lyotard in his work on Les Immatériaux and form part of the larger drama he wanted to stage in his philosophical work. But how, then, did exhibitions (and this exhibition in particular) figure in Lyotard’s attempt to recast Kantian ideas in 1985, in and for the ‘postmodern’ moment?

Les Immatériaux has acquired a sort of cult status among younger French artists like Pierre Huyghe or Philippe Parreno. Drawing upon these artists’ interest, Daniel Birnbaum and Sven-Olof Wallenstein have asked just this question, as to whether Les Immatériaux counts as philosophy or possibly as a way of making philosophy.4 But it was also a question Lyotard asked at the time of Les Immatériaux, impressed as he was by Daniel Buren’s remark that what large-scale exhibitions like documenta really show is the show itself. The remark would stay with the philosopher: later, in the 1990s, Lyotard would refer to pictures of exhibitions as ‘presentations of ideas’, which, in contrast to mere ‘documentations of history’, would suppose another idea of archive, related to theatre (or to sound or music), and of the scripts through which they are reproduced.5

Les Immatériaux was a ‘presentation of ideas’ in the specific sense of ‘presentation’ and ‘idea’ which Lyotard was trying to articulate at the time. It thus linked to another striking aspect of Lyotard’s curatorial experiment – the role and nature of accompanying research, or the role of ‘ideas’ and their ‘address’ in the style of philosophical teaching then current in Paris. With Les Immatériaux, the philosophical seminar would enter into the context of museum research, creating new relations which Lyotard would later evoke in his account of the experience. In the ‘open’ seminar, he would present ideas put forward in a suggestive philosophical text called ‘Time and Matter’, later published in a collection of essays entitled The Inhuman.6 The essay makes interesting reading today, in light of the current interest in exhibitions: in it, Lyotard sets out the larger philosophical ‘idea’ he hoped to ‘present’ through Les Immatériaux. What becomes clear is that Lyotard’s title concept of ‘immateriality’ was different from that of the ‘dematerialisation of art’ associated with the presentation of ideas in what came to be called ‘conceptual art’, and, in particular, ‘institutional critique’. The question thus arises of how this idea and this exhibition are related to that earlier ‘conceptual’ moment in the ‘dramatisation of information’, when the whole idea of the exhibition (or ‘presentation’) was rethought in a manner often opposed to a certain kind of Kantian aestheticism.

In other words, we might consider Les Immatériaux as part of a possible ‘history of exhibitions’, involved with the ‘dramaturgy of information’ and with the role of time, matter, and technology in this history, which would, in turn, intersect with a larger unfinished philosophical history of different ideas of ‘exhibition’ – of ‘presentation’, ‘showing’ or ‘appearance’ – in the history of aesthetics. This history would encompass, for example, ideas formulated in the 1930s, such as Walter Benjamin’s distinction between ‘exhibition-value’ and ‘cult-value’, the related distinction between vorstellen (to present) and herstellen (to construct) in Heidegger’s lectures on the origin of the work of art, and, later, Hannah Arendt’s idea of ‘the public’. To pursue this history would be to ask: how does one ‘present ideas’? What role does ‘information’ play in this history, perhaps displacing, as El Lissitzky already saw long before the advent of digitisation, the age-old literary culture of the book? What function do visual art institutions play in this history? How does the rise of so-called ‘conceptual art’ in the 1960s and 1970s, in particular what Buchloh would later isolate (with a nice paradoxical Adornian touch) as its ‘administrative aesthetic’, effect this history? And how was this history taken up again or posed anew in Lyotard’s philosophical showroom at the Centre Pompidou?

In fact, Les Immatériaux (the plural is crucial) was initiated by the architecture and design department of the Centre, and as such no doubt owes much to the model of the industrial exhibition fair, itself a precursor of today’s art fairs, a model already evident in Lissitzky’s own sense of exhibition as a new art-form. Lyotard was keen to insist that the aim of Les Immatériaux was not to display objects, but to make visible, even palpable (and so ‘present’) a kind of ‘post-industrial’ techno-scientific condition, at once artistic, critical and curatorial. Far from the informational ideals of ‘communication’, Les Immatériaux presented a condition of unease, a sense of disarray, itself given and facilitated by the great aesthetic figure of the labyrinth.

In his own art of presentation, drawing on Dziga Vertov, Lissitzsky would use montage in industrial shows, thereby disrupting a linear perception of history, in what he would call an exhibition ‘kino-show’. As Lyotard’s ‘Time and Matter’ essay makes plain, the problem of disrupting narrative is itself an aesthetic idea, central to the notion of ‘presentation’ in cinema, and in particular, to Deleuze’s great account of it, published the same year as Les Immatériaux.7 Thus, we can now see that Lyotard’s exhibition was not unrelated to more recent curatorial efforts to bring artists’ uses of film back ‘into the light’ of exhibition as well as of critical history – as in, for example, Philippe-Alain Michaud’s Images on the Move exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in 2006. Deleuze, of course, had presented post-war European cinema as a great ‘laboratory’ for new ideas of time and its direct and indirect ‘presentation’, seeking in it a picture of research and exchange not simply across the arts, but also with philosophy, ideas which he would later pursue.8

It is this notion of ‘research’, and of ‘connections’ between philosophy and art, that is found in Deleuze’s 1985 essay on ‘Mediators’ (more precisely translated as ‘Interceders’), which in turn would lead to the problem of ‘information’ and ‘control’ in the history of cinema.9 It is tempting to imagine Lyotard, in a very different way, and in relation to the question of information technologies, as trying to introduce this idea of philosophy ‘interceding’ in and with the arts into the exhibition context. Les Immatériaux, with its strange ear-phones supplying the visitor with a theory sound-track and its room of computer consoles (absent from prior technology exhibitions such as Kynaston McShine’s great Information show at MoMA in 1970), thus came at a particular juncture in critical theory and research, art and philosophy. In Lyotard’s labyrinthine theatre of the new (post-cinematic) ‘condition’ of information, ‘immateriality’ was no longer conceived in terms of freeing concepts or ideas from all materials, but, on the contrary, of shifting the idea of ‘materiality’ away from that of ‘formed matter’ (including the ‘modernist’ distinction between form and content) and towards the ‘techno-sciences’ and the city.

More generally, then, we might imagine Les Immatériaux as an extravagant staging of a peculiar moment in the role of information in the history of aesthetics after so-called ‘modernism’, yet before the ‘contemporary’ configuration of biennials that was already taking shape in the 1990s, within or against which the question of a new ‘history of exhibition’ now itself arises. One way to see this in-between status of Lyotard’s exhibition is through his own wry, melancholy writings of the 1990s, which would take up the theme of the postmodern in increasingly anxious terms, often with a light humour encapsulated, for example, in the little postmodern fable of Marie, in a now long-gone moment of Asian ‘Pomo’, sipping cocktails at a ‘cultural centre’ in Tokyo: ‘Marie tells herself, raising her glass along with the centre’s staff, that deep down those managers are good only if they keep making renovations. Museums, cultural institutions are not only repositories, they are also laboratories. They are truly banks.’10

In such semi-biographical ‘fables’ and other writings from his last decade, we can read Lyotard’s own responses to a new ‘contemporary’ configuration, for which 1989 (or the end of the Cold War) might serve as a take-off date. More specifically, in the new ‘contemporary’ condition of art that was then starting to take shape, we can perhaps identify, in hindsight, two larger questions with which the resulting configuration would become entangled. On the one hand, there is the question of globalisation, in which Europe no longer monopolises history, Paris is no longer the Capital, and Revolution no longer constitutes the political horizon, as it seemed in the nineteenth century when ‘modernism’ was born and Hegel proclaimed the end of art. Indeed, Europe is a now a new idea among others in the arts, where the ‘grand stories’ of modernism or the avant-garde – exemplified by Alfred Barr’s famous views on the presentation, acquisition and collection of ‘modern art’ – now seem increasingly ill-adapted to ‘contemporary’ conditions. At the Centre Pompidou, of course, 1989 was the year of the exhibition Magiciens de la terre, with its non-European ‘representation’. But beyond the sociological or statistical question of the ‘representation’ of non-Western artists or art-forms in exhibitions, there is, on the other hand, a question that was central to Lyotard’s thinking at the time: the nature of ‘spaces’ or ‘zones’ of thinking or ideas, and the role cities play in them – that is, the question of where new ideas come from or the geography or ‘territoriality’ of thought. Thus ‘borderland Europe’ comes to play a key role in questions of immigration beyond the ‘centre-periphery’ or ‘network’ or even ‘clash of civilisation’ models of globalisation distinguished by Etienne Balibar, whose own question of a ‘trans-national citizenship’ takes up the notion of ‘deterritorialisation’ as a condition of thought, art, the relations with one another, and their particular relations with ‘local’ conditions.11 But this question of ‘global’ art ties into the second question, namely, of the role and nature of the ‘contemporary’ art that corresponds to or is conditioned by this ‘globalisation,’ that exposes it, disrupts or questions it. More generally, one could argue that Les Immatériaux marked the beginning of a reflection on the question of how the ‘contemporary’ itself forms part of interactions across borders irreducible to the grand nineteenth-century division of ‘modernity’ and ‘tradition’.

It is of course impossible to analyse here the fairs, biennials, new audiences and collectors involved in today’s ‘global contemporary’ art, which was taking shape at the turn of the 1990s, the sheer volume, geographical and financial scope of which have so dramatically changed the very conditions of making as well as viewing art. But we can see its impact through another crucial question that emerged in art after the 1980s: that of the fate of the modern-contemporary distinction and particularly the role of ‘information’ and ‘materiality’ in this distinction. We might see Les Immatériaux in terms of a shift in the way this distinction is drawn or in the very idea of ‘contemporary art’.

It has been customary to take the 1960s and 1970s as marking a turning point when, for the first time, ‘contemporary art’ found itself in contrast or opposition to ‘modernist’ art. In those years, in particular but not only in New York, the idea of art seemed to free itself from a series of distinctions in which it had been enclosed – production in the studio versus exhibition in the white cube, art versus everyday life, information versus popular culture. Disentangling itself from such divisions, emancipating itself from such institutional forms, contemporary art gained access to a new ‘outside’ in which visual arts and art institutions, including ‘alternative’ ones, played a key role, without exact parallels for the ‘modernisms’ in other fields. But as artist Andrea Fraser still worries that ‘we are the institution’ and that there is no longer any ‘outside’, one can only sense that, all these years after Les Immatériaux, the mainstream/alternative, outside/inside distinctions have lost much of their edge, having themselves become part of official art historical and museographic discourses, a nostalgia even, as if, in the end, they were just another variant of ‘modernism’ or European ‘art since 1900’. The question then arises of the new forms that the contemporary-modern would assume in the 1990s in an increasingly global scope, and the impact they would have on the ‘history of exhibitions’. Lyotard’s writings, and Les Immatériaux in particular, might be read in terms of the passage from one sense to the other of ‘contemporary art’, as ‘dramatising’ a key moment in between the two and the feeling of ‘disarray’ that accompanied it.

Taking place in Paris a decade after the shift in ‘information’ and art that accompanied ‘conceptual art’, and prefiguring many of the digital technologies that now surround us, Les Immatériaux was, of course, pitched in terms of the debate on the ‘postmodern’. At the time Lyotard tried to get rid of the idea, replacing it with a project of ‘re-writing modernity’, but to no avail. Even today he is mostly remembered for that idea, which in the meantime has lost any critical edge it once had, giving rise to a literature of lament and despair, of which, indeed, Lyotard’s own increasing ‘melancholy’ tone now seems an anticipation. Back in the 1980s, in what he called the ‘Beaubourg effect’, Jean Baudrillard had entertained a kind of implosion fantasy about the cultural products endlessly recycled through the pipes of the new Centre Pompidou. But even that would no longer be possible in the ‘perfect crime’ through which the new ‘contemporary art’ of the 1990s, with its false conviviality, killed off the very idea of ‘transgressive art’: the ‘Beaubourg effect’ would be superceded by the Bilbao effect.12 Instead of objects endlessly recycled in the exhibition-incinerator of a new ‘pomo’ Paris, art-objects would travel outside, enriching local cities with dramatic architecture, travelling exhibitions and related intellectual ‘panels’, and with arts of convivial ‘participation’ for younger ‘new audiences’. When Rosalind Krauss dubbed the Guggenheim the real ‘pomo’ or ‘late capitalist’ museum, she thus pointed to a new picture of art practices, in relation to or against which the idea of ‘contemporary’ art would have to define itself.13

We can distinguish three models and related research themes in which the question of exhibition intersects with the larger issues in aesthetics, whose Kantian sources of the idea of a sensus communis Lyotard was trying to rethink. First, there is Lyotard’s increasing interest in Malraux, to whom the philosopher devoted a biography. Indefatigable, Lyotard hoped to recast Malraux’s old question of ‘silences’ in terms of his own idea of making visible, audible, and thus ‘think-able’, what cannot be seen, heard or thought, and to recast the ‘imaginary’ side of the museum accordingly. Lyotard articulated this question in 1993 as a search for an ‘ontology of the imaginary museum’.14 Tinged with a melancholy that drew him back to Adorno, the idea was then often tied up with ‘bearing witness to the unpresentable’ – for Jacques Rancière, the objectionable feature in Lyotard’s work and his notion of the sublime. But one might pitch the idea in another way, in light of Douglas Crimp’s well-known essay on photography, which, drawing on Foucault, set Malraux’s role against the larger question of the intersections of exhibition with forms of knowledge and art.15 In Foucault’s ‘Fantasia of the Library’, one already finds the great Flaubertian theme, reprised by Crimp, of the ‘stupidity’ (bêtise) in the Museum and in the Library, and its peculiar relations with ideas and their ‘presentation’. Through Malraux, Foucault aimed at the time to extend the break with the encyclopedic dream that haunted Hegel’s philosophy, to the Museum and Manet’s relations with it (even though Foucault later destroyed the book he had projected on the topic).16 However, we might see the idea of the bêtise of museological or encyclopaedic knowledge differently, captured in Peggy Guggenheim’s famous quip: it can be modern, it can be a museum, but not both. Perhaps there is always a museological ‘stupidity’, namely, the arrangements and stories through which the Museum reconfigures and presents the objects in its ‘bank’, which new or ‘contemporary’ art is always breaking away from and exposing, through another kind of vital research or laboratory, as with the complex fate of the ‘salon des réfusés’. In Lyotard, this ‘outside’ element, matching the kinds of dissensual ‘events’ he associated with ‘presenting the unpresentable’, was in turn related to a notion of the ‘theatricality’ of exhibitions: the sense in which they are like ‘scripts’ to be performed in new ways or altered circumstances – either inside or outside museums and with institutional histories.

We thus find a second theme and related discussion in Lyotard’s writings from the 1990s. Exhibitions, beyond the reproduction of given forms (‘stupidities’) of knowledge, can be involved in the ‘presentation of ideas’ as part of laboratories of research, to use Dorner’s word echoed in Marie’s remarks in Lyotard’s fable. Beyond the figure of the labyrinth and the use of dioramas in Les Immatériaux, Lyotard associated the question of such ‘presentation of ideas’ with the idea of ‘dramaturgy’ or theatricality. One always dramatises new ‘ideas’ – as Deleuze already saw in Nietzsche and Wagner – and exhibitions can be one way of doing this; the notion of ‘imaginary’ which Lyotard was trying to rescue from Malraux, was another. It is perhaps this theatrical or imaginary side of Les Immatériaux – Lyotard’s interpretation of Buren’s ‘showing the exhibition’ – that would appeal to Huyghe and Parreno: the creation of a kind of ‘environment’ for the enactment of ideas. In the ‘presentation’ or ‘dramaturgical’ side of Les Immatériaux, there is also another theme that runs through Lyotard’s later writings, captured in his idea that the ‘scenography’ of the exhibition should simulate, in the heart of metropolitan Paris, the new sort of sprawl or ‘con-urban’ space he had encountered in California, where only the car radio allows the traveller to know when she or he is passing from one city to another. For Lyotard, this shift from nineteenth-century ‘metropolis’ to the new ‘megapolis’ raised questions of ‘bigness’ and ‘generic urban conditions’ – questions later developed by Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau. The problem of exhibitions and cities, in part under Koolhaas’s influence, would continue to be explored in the 1990s by, among others, Hou Hanru, with Cities on the Move and, more recently, in opposition to the ‘urban fictions’ of Beijing’s spectacular architecture.17 The problem of the fate of Malraux’s ‘imaginary museum’ in the new global ‘mega-polis’ was Lyotard’s way into this problem at the time of Les Immatériaux: ‘As the cultural institution proper to the mega-polis, the museum is a kind of zone. All cultures are suspended there.’18

The notion of ‘zone’ opens onto a third area, indeed a third zone in Lyotard’s late reflections on exhibitions as key institutions in a new global-urban culture. Cities of course have long been seen as ‘catalysts’ and ‘laboratories’ of ideas: in the 1930s this trope can be found, for example, in Georg Simmel’s essay on the ‘Geist’ (or ‘mental life’), in the diagrammatic childhood memories of Walter Benjamin – first intended for a photo exhibition – and, later, in the ‘psycho-geographies’ of Situationist dérive (wandering). The sense of a ‘deterritorialised’ sociability as a condition of democracy was precisely what Deleuze admired in Simmel, the same sense that can be discerned in Fernand Léger’s painting Men in the City (1919, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York). But in taking up in turn the theme of philosophy as ‘the city thinking’ for, or in the conditions of, the ‘mega-politan’ city, Lyotard drew attention to the idea of ‘zones’ not simply as a matter of graphic design (like in Apollinaire’s calligramme), but also, as in ‘faubourg’ or ‘banlieu,’ as a space for the ‘theatre’ of poetry declaimed in the streets. Just as Benjamin’s brilliant piece in One-Way Street brought together Mallarmé, advertising and graphic design, Lyotard’s ‘zone’ allowed him to tackle how ‘words’ entered art and exhibition spaces, and whether literature or writing was to be found in books or in the streets. Before the ubiquity of compendious online catalogues, Lyotard was worried about how such ‘ideas’ in the con-urban ‘zone’ would spread around the world as part of massive processes of urbanisation. Where would new ‘exhibitions’ of ideas in, or in the outskirts zone of, the ‘cultural institution’ particular to this new global city formation take place? Spiked with the exasperated humour of his late worries about ‘nihilism’, Lyotard’s thoughts on this question – more central than that of including ‘other artists’ or ‘cultures’ in a European tradition – anticipated the emergent zones in which art intersects with new ideas, not simply in Paris and New York, but also Berlin and Beijing, São Paolo or Istanbul. The presentation of ideas, the nature of ‘zones’ for exhibitions in the ‘mega-polis’ thus becomes a new question, not simply in relation to Malraux’s ‘silences’, but also after, or in, its ‘ruins’, when the question of contemporary art is asked anew in and through exhibition.

But how, then, should we construct the history of exhibitions? Perhaps such a history is not one thing, governed by a single logic or narrative but, on the contrary, vital precisely because it intersects with many others. This at least is what is suggested in my little contemporary fable of Les Immatériaux: how this exhibition can now be seen as a point of intersection for different histories going off in numerous directions. We might therefore consider 1985 not simply as a date in the field of exhibitions, but also in theory and research, and hence for that presentation of ‘ideas’ of, and in, art which for two centuries after Kant came to be known as ‘aesthetics’. What new forms might this grand philosophical discipline yet assume in the era of ‘global contemporary art’? How yet might it interrupt, disturb or intersect with on-going practices or institutions of showing art, and so itself form part of a new unfinished history of exhibition and the new ideas of art associated with it?