Once, at home when we were children, we were playing, and my elder brother Michael started to assemble toys and other bits and pieces on the floor around the fireplace in a kind of semicircle. I asked, ‘What are you doing?’ and he said, ‘I’m making an exhibition’. E–x–h–i–b–i–t–i–o–n: it was the first time I had heard the word and it fascinated me. Do I remember this incident because exhibitions came to play a big part in my life? I do not know. But this is perhaps an occasion to re-invest the word with the magical quality it had then.

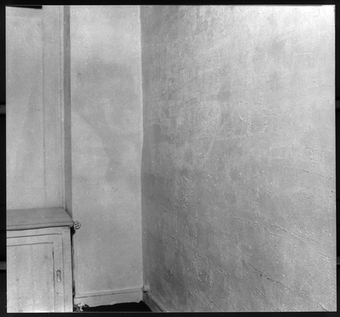

Fig.1

Yves Klein

Interior view of the exhibition Le Vide (The Void), held at Galerie Iris Clert, Paris April–May 1958

© Yves Klein, AADAGP, Paris 2009

I think it can be done because when one considers the multitude of ways in which artists have recast the notion of exhibition, the elasticity they have given the term in our understanding of it, we see that there is a whole poetics there. What I would like to do is to give a sense of this poetics by taking examples of exhibitions, organised by artists themselves, either solo or with close collaborators, at different times and places over the past forty or fifty years, just in order to demonstrate this extraordinary elasticity. There are countless ways of interpreting artists’ work, and one way could be to see it against, or in relation to, the notion of an exhibition, of exhibiting something. In fact, one could start with the basic paradox of exhibition/no exhibition, exemplified by Yves Klein’s Le Vide (The Void), an event which took place at the Iris Clert Gallery, Paris, in 1958. The gallery was emptied of exhibits. The empty gallery was itself the exhibit. In her book on Klein, Sidra Stich has described how the whiteness of the empty gallery was enhanced by several coats of a pure white lithopone pigment applied with a Ripolin enamel roller, blended with Klein’s special varnish of alcohol, acetone and vinyl resin.1 There were other enhancements which, admittedly, seemed only to betray Klein’s political conservatism, for example, the presence of two fully-uniformed Republican guards at the entrance of the gallery, this at a time when Paris was rent by protests caused by the escalation of the anti-colonial struggle in Algeria. But basically, in this event, the philosophical notion of the Void (which is dimension-less) was proposed within the customary conceptual and physical limits of the experience of art, the art gallery. Not surprisingly, attention fell on the reaction of the audience, gallery-goers. Klein published a report of the clamorous events of the opening evening:

9:45 pm. It is frenzied. The crowd is so dense that one cannot move anywhere. I stay in the gallery itself. Every three minutes I shout in a loud voice …. ‘Mesdames, Messieurs, please have the extreme kindness not to stay too long in the gallery so that other visitors who are waiting outside can enter in their turn. Etc.2

The hubbub continued until half-past midnight when the gallery closed and Klein and his entourage repaired to La Coupole, where a table for forty was booked at the back of the café. Klein later noted some of the public responses after the vast crowd had dispersed: ‘Some people were unable to enter, as if an invisible wall prevented them. One day one of the visitors shouts to me: “I will come back when the void is full …” I respond to him: “When it is full, you will no longer be able to enter”. ‘Another visitor, Albert Camus, left a note saying: ‘Avec le vide, les pleins pouvoirs’ (‘With the void, comes total empowerment’).3

In the visual realm, the situation Yves Klein contrived was directly comparable with the sound/silence musical dichotomy or paradox explored by John Cage in his work 4′33″, produced some years earlier in 1952 at the height of Cage’s interest in Zen Buddhism. This entailed the performer, David Tudor, ‘sitting motionless at the piano for 4 minutes and 33 seconds, without playing a note. The sounds of unrest in the audience constituted the contents of the work.’4

A very nice, very sharp, re-interpretation of Klein’s void is found in Gabriel Orozco’s Caja de Zapatos Vacía (Empty Shoebox 1993) which can be seen as a small, portable void, enabling him to pose the same question as Klein within the large-scale survey exhibitions typical of today’s Biennales and documentas. Empty Shoebox has often caused considerable annoyance when it has been exhibited. Museum registrars despair of the consequences of insuring as an art work a nondescript open box which Orozco insists on placing on the floor or in a corner where it could easily get kicked or thrown away. There has sometimes been the complaint (not least at the Venice Biennale in 1993) that Orozco has lowered the tone of a would-be important mixed show by submitting a slight piece of work, whereas, paradoxically, the modest empty box can become in one’s mind the opposite: an expansive figure of receptivity, openness, possibility, especially by contrast with some of the more laboured efforts around. In the atmosphere of ‘artistic jousts’ that these group exhibitions have become, rather as in the poetic jousts of the past, to accomplish much with minimum effort counts for a lot, and raises the pitch of the vitality that all are seeking.5

This is not to say that Klein was indifferent to the way his monochrome paintings were displayed. On the contrary, he planned his exhibitions minutely, in response to his own process of self-criticism. When he came to make his famous 1961 exhibition at the Museum Haus-Lange in Krefeld, he criticised his own first showing of his Monochromes at the Galerie Colette Allendy in Paris in 1955. These were arranged in a group and, as a result, he felt the public were ‘reassembling the paintings as components of a polychromatic decoration. They could not enter into the contemplation of the colour of a single painting at a time.’6 In other words, they could not feel what Pierre Restany called ‘the density of their optical radiance’.7

I have the impression that few people today have heard of the gallerist Iris Clert, which is sad because she deserves as much recognition as her artists for the way she actively encouraged their experiments, and she is partly responsible for the way they stretched the concept of the ‘exhibition’. One of the most memorable events she hosted was that by her fellow Greek Takis, L’Impossible: Un Homme dans l’espace (The Impossible: A Man in Space) in 1959.

Shortly before, Takis had produced his first ‘telemagnetic’ sculpture, in which metallic elements are held in suspense in the air by a magnet. For Takis, according to the poet Alain Jouffroy, it was a ‘eureka’ moment. He had been searching for a way to go beyond representation and to incorporate a direct source of non-mechanical energy within the work, and one which would manifest itself across distance thereby creating a new kind of sculptural space. Five months before Iris Clert’s event Yuri Gagarin had become the first human to escape earth’s gravitational pull. In the gallery Takis floated the poet Sinclair Beiles in space through a system of magnets. In his condition of levitation, Beiles recited a poem, ‘I am a Sculpture’. He denounced the military use of atomic power and urged that all nuclear bombs be turned into sculptures. The moment was caught in photographs by a young German artist present on the occasion, whose name was Hans Haacke.

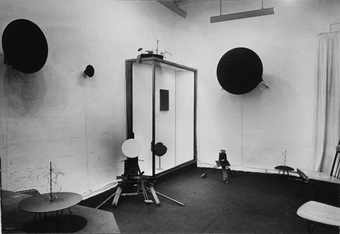

Fig.2

View of the exhibition Vitesse pure et stabilité monochrome (Pure Speed and Monochrome Stability), held at the Galerie Iris Clert, Paris 1958

© Yves Klein, ADAGP, Paris, 2009

Another memorable exhibition at Iris Clert’s was the creative collaboration between Yves Klein and Jean Tinguely,Vitesse pure et stabilité monochrome (Pure Speed and Monochrome Stability) 1958. It is, in fact, one of the most fascinating collaborations between two artists – so different from one another – that I know of, for the way it explored, and went beyond a number of basic dichotomies. That between motion and stillness implied in the show’s title is just one of them.

Photographs taken at the time show the gallery interior with the raw look of a rough-and-ready laboratory. Objects constituting the most incongruous combination of machinery and painting squat on the floor or cling to the walls. In another photograph, the sculptor and the painter appear to be interrupted in the midst of their collaborative endeavour and face the camera, Tinguely with a length of electric cable in his hand and Klein holding a paint roller. There is that air of pride and the ‘moment of discovery’. Essentially it was a moment of the dismemberment of old notions of space and the boundaries of artistic genres, and the discovery of a new concept of space/time by this clash of painting and sculpture. One machine is called The Excavator of Space. Each has a monochrome disc of a different size, a different colour (white, blue or red), spinning at a different speed (from 450 to 10,000 revolutions per minute). An eye-witness, the artist Heinz Macke, described the scene at Tinguely’s studio, a short while before the works were moved to the gallery:

Then our whole attention was caught, hypnotically, by the rotating disc, which was clearly revolving so fast that it appeared to be standing still. ‘Vitesse stabilité!’ Tinguely proudly declared. … The optical sensation sprang from the transformation of the rotating disk into a volume. A virtual, immaterial volume that seemed to hover over the rusty iron contraption like a tiny cloud of colour. I exclaimed: ‘It’s pulsating, it’s breathing, it’s moving, it’s expanding, it’s turned into thin air!’ And Yves beamed, and Tinguely danced on the spot, revolving on his own axis and beating his breast.8

While in motion, painting maintained its quality of contemplative stasis, evoking the ‘void’ that Klein had proposed a few months previously. But, while transcendental, it remained anchored in the world of everyday exertion and bricolage represented by Tinguely’s machines. Some massive lumps of iron stabilised the spinning discs and absorbed their vibrations. Tinguely called this the ‘chassis’. The combination may explain the vaguely anthropomorphic appearance of these objects, with Klein’s disc as the dreaming head and Tinguely’s mechanics as the workaday body.9

The paradoxical relationship Klein proposed between exhibition and no-exhibition, echoing the enigma of the ‘full void’, has an extension in the work of Alberto Greco. Greco was born in Buenos Aires, spent time in Paris and Spain, and was an admirer of Klein. Greco felt intensely the artist’s contradictory pull between Life and the Institution of art, between Living and Representation, and he braved the Institution’s ridicule and the citizens’ annoyance by drawing a line in chalk around passers-by in the street and signing it. He called his practice ‘Vivo Dito’. Vivo means living and Dito is derived from the Spanish dedo, a finger, hence the act of pointing. Greco wrote: ‘The artist will not show any longer with the picture but with the finger’. This must be one of the most fluid, fleeting and ephemeral incarnations of the ‘exhibition’ that one can think of. Greco did, however, continue to paint until he ended his own life, at the age of thirty-four, in 1965.

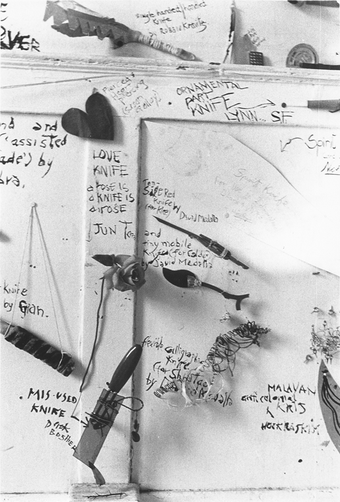

Fig.3

Susan Hiller

Work in Progress (as shown in Matt’s Gallery, London 1980)

Courtesy the artist and Matt’s Gallery, London

© Susan Hiller

I should like to come now to more recent times and to consider two works where the concept of the exhibition is stretched in a different way. One is Susan Hiller’s Work in Progress, which took place at Matt’s Gallery in London in 1980; the other David Medalla’s Eskimo Carver, which was mounted at Artists for Democracy’s precariously held space in Whitfield Street W1 in 1977. Hiller’s Work in Progress was an exhibition which started off as one thing and ended up as another. A display of her paintings went through a material deconstruction and a formal transformation at the hands of the artist herself over the period the show lasted – as if one authorial self, or one part of the psyche, was slowly and visibly ceding to another, by way of the same materials. Jean Fisher has given the following account of the work:

The artist had begun by moving into the space her work table and several paintings that had been exhibited earlier. She then proceeded to unravel the weave of one canvas, thread by thread. At the end of each day, the pulled strands were hung in skeins on the wall. At the end of the first week, each skein was hand-worked, by knotting, looping or braiding, into individual three-dimensional ‘thread drawings’ or ‘doodles’, whilst the remaining canvases were cut into small rectangles, baled into little bundles and given a date stamp. The ‘doodles’ were pinned to the walls and the bundles displayed on small shelves and exhibited during the second week. … Among the references that this play on weaving evokes is the classical story of Penelope who wove by day and unravelled by night whilst she awaited the return of Odysseus. As Susan Hiller commented, this activity has been used to generalise the work of women artists as a ‘predilection for the monotonous – repetitive and ritualistic’. She proposed instead that the Penelope theme represented an attempt to ‘keep time static’ – the ‘false sense of permanence’ that is attached to art objects – and ‘has nothing to do with repetitive obsessive work for its own sake’.10

Fig.4

David Medalla

Eskimo Carver 1977

© David Medalla

At the basis of weaving is the motif of the cross. Individual threads cross with others to form the resilient mesh. Hiller dismantled this order, or rationale, and turned it into the disorderly knotting of the loose threads, giving the objects a visceral, organic presence. Painting became sculpture became drawings; and order turned to chaos to become a different sort of order.

The context for David Medalla’s Eskimo Carver was an art-political organisation active in London in the mid 1970s which pledged to give artistic and material support to liberation movements around the world. Its first action was to mount a festival in support of the restoration of democracy in Chile. The event took place a year after the Pinochet coup and was held at the Royal College of Art in London. Later Artists for Democracy moved to squatted premises in Whitfield Street and Medalla’s work was staged there. I always felt that this somewhat obscure event was in fact a landmark exhibition of the 1970s.

Medalla had been considering a performance in which the periods of human history, from the caves to the twentieth century, would each be represented by a knife singing its own song (for example, the palaeolithic flint knife, Leonardo da Vinci’s scalpel for cutting the cadaver, etc). At the same time he came across Tom Lowenstein’s re-translations of the Danish anthropologist Knud Rasmussen’s transcriptions of Eskimo oral poems made originally in the 1930s. These were thrown into sharp relief by stories, current then in English newspapers, about the building of an oil pipeline in Inuit territory in Alaska, a huge project undertaken by transnational companies.

Medalla’s event consisted of several elements. There was an exhibition of his drawings and transcriptions of Eskimo poetry, and a performance, Alaska Pipeline, in which the British tabloid newspapers’ glorification of pioneering pipe-layers combined with a racist denigration of the Inuit, effectively condemned itself. The third part was an invitation to visitors to make knives out of non-perishable garbage which had been collected in the neighbourhood and piled in a corner. The ambience opened people’s minds in a certain way. The Inuit people have given some of the most succinct and eloquent descriptions that exist of the mixture of desire, anxiety and pleasure which is present in the human urge to compose poems and songs. They traditionally have a democratic, non-professional practice of creating them.

As the collection of knives built up, everyone, including the artist, was astonished by the variety of peoples’ contributions. They ranged from very functional-looking knives to remarkable kinds of fantasy. Medalla always stressed that his propositions were easy to enter.

People can walk in and out of my situations … they are dependent on each person falling back on his or her own resources … [their aim is] to infuse people with a certain kind of enthusiasm, to trust their own capacities to be creators … Artistic propositions are really just processes … people can be in them like oceans or seas, you can just sort of swim in them.11

Medalla’s participatory installations were from the beginning a means of breaking with certain ingrained taboos and restrictions governing the artistic scene. Through them he put forward the startling idea of invading the monocultural, monological, monolithic institutions of the art world by the sheer pressure of a latent creativity. Eskimo Carver could be said to have anticipated the wave of sculpture made from the scavenging and re-presentation of waste during the 1980s by a younger generation of ecologically-minded artists. For Medalla, however, the problems of consumerism and commodity production could not be illuminated by the mere creation by the artist of a new object, since they were bound up in the relationship between the artist and the public.

You cannot say that one knife is better than another. It is really a show – or a concept if you like – that effectively destroys the idea of the unique art object … If you put such a proposition in a public place, literally it’s an endless proposition, there is no end to people coming in and making knives. I could easily inundate, say, the Tate Gallery.12

At the same time Eskimo Carver was a kind of critico-poetic parody of the workings of ethnographic museums. And therefore it linked one part of the system – the context of contemporary art – with another part, the context of ethnographic art, and the image made by ethnographic museums of ‘other cultures’.13

There are very nice connections to be made between Medalla’s proposal and a work by Claes Oldenburg: what became known as the Ray Gun Wing of Oldenburg’s MouseMuseum project. This was started in the 1960s and continued to be added to throughout the 1970s. There was no direct contact between these two shows, or these two artists. Oldenburg’s work had aspects of an actual archival collection of toy ray guns – a perfect Pop artefact – bought or found by the artist. But as time passed the allusion to the ray gun model or type became more and more abstract, a sort of spectre which might be recognised in any chance configuration of discarded materials or ephemeral circumstances. The whole concept of the exhibition and the museum of preserved objects seemed to therefore dissolve itself into life and the flux of time. Oldenburg’s action appeared to be a perfect of example of what Robert Smithson proposed in a trenchant critique of the fetishisation of the art object written in the 1960s:

A great artist can make art by simply casting a glance. A set of glances can be as solid as any thing or place, but the society continues to cheat the artist out of his ‘act of looking’, by only valuing ‘art objects’. The existence of the artist in time is worth as much as the finished product. Any critic who devalues the time of the artist is the enemy of art and the artist.14

However, an interesting difference between Eskimo Carver and the Ray Gun Wing is that the variety of knives in Eskimo Carver grew from the variety of minds or psyches that devised them within the ‘arena of expectation and challenge’ that the artist created; whereas the variety of ray guns derived from one person’s sophisticated eye. Could there be an echo here, perhaps, of the difference between the multi-functional nature of knives, which can be used for cooking or killing – the knife cuts benignly or cruelly – and the uni-functional nature of the gun: to destroy the other?

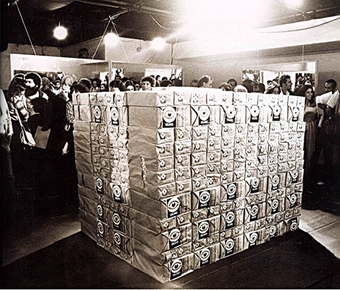

Fig.5

Cildo Meireles

O Sermão da Montanha: Fiat Lux (The Sermon on the Mount: Fiat Lux) 1973–9

Courtesy Galeria Luisa Strina

© Cildo Mereiles

If the visitors to an exhibition became its co-creators they would explode its temporal and spatial limits. And yet the artist’s relation with the visitor could just as easily create a sense of uncertainty, confusion, and even fear, that, depending on the poetry with which it was handled, could lead to a sharpening of the critical sense. A practice of deception could lead to a form of enlightenment and potential. In conclusion, I should like to refer to two further exhibitions here: Cildo Meireles’s The Sermon on the Mount: Fiat Lux, staged in 1979 in Rio de Janeiro, and João Penalva’s The Ormsson Collection Presented by João Penalva, which was held at the Museu da Cidade in Lisbon in 1997. These two works/exhibitions come out of very different situations. Cildo’s Fiat Lux was made under Brazil’s military dictatorship, at a stage where the oppressive conditions had been endured for some time, and Penalva’s work under conditions of liberal democracy and postmodernity. Yet both exhibitions engineer an uncertainty between what is real and what is fictional, and both do so in terms peculiar to the habits and rituals of the world of art.

Meireles’s work plays on the art world’s tradition of the private view or vernissage, although in fact it lasted twenty-four hours. Visitors arriving at the Cândido Mendes building in Rio descended into a claustrophobic basement where they were faced by a huge cube comprising stacked packages of – they would have recognised this instantly – boxes of matches of the familiar Fiat Lux brand. These goods looked as if they had been brought directly from a warehouse. There had been no sign at the entrance, nor any receptionist or desk that would have indicated that this was an art gallery and therefore comfortingly confirmed that one was present at an exhibition. Instead, the stack was surrounded by five men with the unmistakable dress and demeanour of bodyguards, government agents, or even members of a Death Squad. And they behaved aggressively, inspecting the packages and pushing people about. Furthermore, their shoes, indeed the shoes of everyone present, rasped against a floor of rough paper of the kind used to strike matches, the sound of which was amplified through hidden microphones.

Additionally disconcerting was the presence of mirrors on the surrounding walls. If one looked into the reflection of the assembled company one also caught sight of Jesus Christ’s Beatitudes from the Sermon of the Mount, which were inscribed on the glass: Christ’s critique of society and his elevation of the powerless.

The response of many was uncertainty, fear and apprehension. They remember that it was impossible to tell at first what was real and what was not. Some were angry, thinking that the art event had been invaded by the authorities as an aggressive symbol of the dictatorship’s power: ‘Even here, too?’ they asked themselves. Others were afraid that the huge accumulation of phosphorous could explode. At one point, this became a serious possibility as a few rash spirits took matches from the packages and began striking them. The film shows that during the evening the military police arrived: real police, not the actors who were playing the bodyguards. But they too were uncertain what was going on. There was nothing for them to do, and so they withdrew.

The brief duration of the piece and its immediacy for those who were present may disguise its multiple layers of meaning, its wit and rich ambiguities. Even the biblical title is a mixture of New and Old Testaments, of a societal and cosmological reference. Then, in terms of genre, there is a deft interplay between sculptural, spatial and performance elements. There is a dual link with moments in art – with the historical avant-garde in the shape of the Duchampian readymade, and with the then contemporary movement of minimalism, which Meireles both paid homage to and exceeded. Meireles is of the generation that re-encountered Marcel Duchamp and discovered further possibilities in his ideas. Echoing the procedure of the readymade, the artist simply went out and bought a commonplace commodity – a box of matches – shifting it from a familiar to an unfamiliar context. Then he went a step further: by accumulating the box in excessive quantities beyond the pattern of its normal use, he showed that its state could be transformed qualitatively into something else – from one of safety, domesticity and containment to one of illegality and danger. This was simply a problem of the contradictory nature of the one and the many. The cube of matchboxes may echo the minimalist work of artists like Carl Andre, Don Judd and Sol LeWitt – monumental works built from the incremental repetition of identical elements, but in Meireles’s case the incremental process creates a new state of the material: its explosivity.

This brings allegory into the equation, something that was anathema to the minimalists. The central feature, the great cube, is a symbol of fire and light. The whole ensemble may then be seen not only as a social critique, but as an allegory of art itself, a complex one because the presence of the guards can be read in two ways. Either the cube is guarded because of its potential physical danger to the public, casting the action of the guards in a benign light; or it is guarded in order to repress and inoculate enlightened and emancipatory ideas, of which it is the symbol. It is precisely by means of its ambiguities between a real and a fictional scenario, between the actual and the symbolic function of art’s materials, that the piece sharpens our thinking and our ability to tell these two states apart.15

A number of these questions resonate in a more leisurely and fastidious way in Penalva’s work The Ormsson Collection. It was the result of an invitation to exhibit in the Pavilhão Branco, an airy modern building set in the eighteenth-century gardens of the Museu da Cidade in Lisbon. Penalva had been commissioned to make a personal selection from the Museum’s collection, and he decided to extend the curatorial role he had been given by a further remove. By borrowing works here and there, including from the Museu da Cidade itself, Penalva presented the fictitious collection of a fictitious private collector, the Icelandic-born Loftur Ormsson. Ormsson’s particular passion was for ‘pairing’, to search for the ‘pair’ of any work he possessed. He did this according to his own notion and for his own amusement (he had no thought of exhibiting his collection). An accompanying book was published containing an elegantly crafted interview in which Penalva spoke of the mysterious connoisseur to Isabel Carlos. The fiction was revealed only at the end of the exhibit, just before leaving the space, by the inclusion of a list of the provenances, or lenders, of the objects, a clue, however, that was missed by one Portuguese newspaper reviewer, much to Penalva’s amusement: ‘I should tell you that a less attentive critic wrote in a newspaper something along the lines of what is art coming to when artists take private collections, put them on display and call this art!’16

The pleasures of this show, for me, lay in the state of uncertainty it played on. I was not so credulous that I did not wonder if Penalva had invented Ormsson; nor was I so initiated that I did not feel that Ormsson could be real. The frisson of certain/uncertainty seemed to revolve round the suspicion that the work was a self-portrait, or the creation of an alter ego for at least part of the author’s personality. Thus, we learn from Penalva’s description of their friendship that Ormsson was a person who would ‘revel in oddities, and take an immense, a serious pleasure in their structures’, that he liked ‘the odd thing that no one pays attention to’, that he ‘would have made a great spy’.17

Speaking in general terms, Penalva describes his intention in the Ormsson work as being to point out and therefore to question what he calls ‘the aura of museological authority in the fabrication of a truth’. The museological protocols are meticulously observed and thoroughly convincing. But then again there is the more personal question of the identification/non-identification with the fictional character, the truth of the mask. No doubt the fictional collection is more interesting than many real collections. In his interview Penalva deploys elaborate strictures to dissuade us from interpreting the relation between the pairs of objects in Ormsson’s collection, by presenting Ormsson as such a fastidious man that he might well view our efforts as crude.18

Such are the subtleties of the piece, whose feints and deceptions over the conventions of exhibiting art are a far cry from, but are somehow intimately related to, Yves Klein’s void at Iris Clert’s.