As an art critic and curator, Lawrence Alloway established his reputation in the late 1950s alongside fellow members of the Independent Group (IG), including the architectural critic Reyner Banham and the artists Richard Hamilton and Eduardo Paolozzi.1 The members of the IG had a shared interest in the visual and iconographic qualities of American popular arts, with the movies providing a particular fascination. Only Alloway, however, wrote consistently on film, producing a small body of published texts on the topic in art and film journals and in mainstream magazines.2 His critical work on the movies culminated in 1969 with the programming of a series of screenings of American action films at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The catalogue accompanying the programme, Violent America: The Movies 1946–1964, was published two years later, and included five essays by Alloway on realism, expendability, iconography, violence, and the industrial context of film.3

What links the five essays, and indeed all of Alloway’s early work on film, is the idea that the movies are best understood as an industrial art and therefore must not be approached in terms drawn from the critical appreciation of the fine arts. An individual film, in and of itself, is less important than its place within the run or set of films that it is produced alongside. Seriality and the popular film is what interested Alloway, not the great work or masterpiece. Understanding how one movie’s commonality with another produces meaning and significance that far outweighs whatever might be drawn from the contemplation of an individual work animates his film criticism. Film should not be viewed as a young pretender to the fine arts or as its unwanted stepchild. The industrial and popular arts, Alloway argued, should be judged and evaluated on their own terms and within the contexts in which they are produced and consumed. Alloway takes this stance on film’s cultural status at the same time as other critics are vociferously claiming film as an art, even when it is a product of the Hollywood machine.

Two articles, published in November 1966 and February 1968 in Arts Magazine and Vogue respectively, are representative of Alloway’s film criticism.4 These pieces offer brief evaluations of contemporary film culture, including a barbed retort to the trend in auteurist hagiography and a consideration of the medium specificity of film. Within this mix, Alloway notes film’s vibrant role in the collapse of readily identifiable markers of distinction between the fine and the popular arts, and he does this with an enthusiast’s attention to detail and nuance, and a cinephile’s appreciation of style. What is remarkable is that he achieves this in the unlikely form of a 1,500-word review of Roger Corman’s The Wild Angels (1966), the first movie to feature Hells Angels as protagonists, and a 2,000-word article built around viewings of a film by the artist Andy Warhol and a detective picture starring the singer and actor Frank Sinatra.

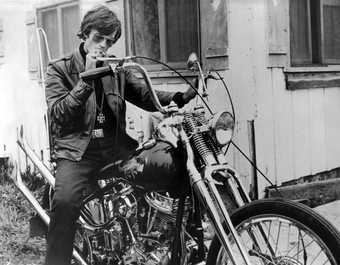

Fig.1

Film still from The Wild Angels, showing the actor Peter Fonda on a motorbike 1966

© A.I.P./ The Kobal Collection

Alloway’s Arts Magazine review of The Wild Angels is placed between an article on avant-garde arts in New York’s Lower East Side and a think-piece by the musician Charles Mingus on the question of where jazz is going. On the surface, this immediate context of, on the one hand, youthful, bohemian rebellion, and on the other, the stated desire to leave behind the ‘jazz outhouses … whiskey hustlers and ringing cash registers’ for a more attentive and respectful audience, appears to be an apposite one for Alloway’s review.5 All three articles are indicative of the new, expansive range of topics covered in contemporary arts magazines, an openness to forms other than those traditionally associated with the fine or higher arts. There is, however, something unsettling or provocative in Alloway’s review of a film about an outlaw motorcycle gang festooned in Nazi regalia (fig.1); it is as if he is testing the limits of the art establishment’s new found permissiveness. Unlike the subjects in the articles that bracket Alloway’s review, Corman’s film makes not the slightest concession to any accepted notion of artistic value or practice, instead it loudly and luridly proclaims its sensational and crass appeal. In the preceding article, the bohemian avant-gardists shun their middle-class background, finding a ‘compatible environment’ on the Lower East Side, isolated from ‘the mainstream of New York life’, while in the succeeding one, Mingus looks to escape the confines of a music born out of proletarian drinking holes and dance cultures. The bohemian rejects conformity by travelling down the cultural ladder – a form of slumming – while the musician transcends his situation by climbing up the ladder to a more refined, cultivated and civil space. Between these two familiar cultural movements of ascent and descent, The Wild Angels stands still, making a big noise.

As a leading art critic, Alloway was acutely conscious of the film’s non-art status; however, he does not appropriate the movie and make it a part of, for example, a pop art lexicon, which would be a safe critical move. Instead, he deals with the film on its own terms by paying attention to its particular and shared attractions. The sensational topic of outlaw bikers is what drew contemporary critical comment, but Alloway argues it is a mistake to focus on this aspect, because it obscures what the audience already knows, but which the critic overlooks: that meaning in formulaic movies is governed by convention and its modification. For Alloway, the task of the critic is to deal with this apparent contradiction between stasis and change, not with a film’s claims to uniqueness. The challenge Alloway posed is to understand film’s unstable combination of repetition and difference.6

If Alloway was exploring the extent of an art magazine’s openness to apparently indiscriminate or non-art topics, such as a Corman exploitation movie, he was no doubt testing the limits of what topics were acceptable in a fashion magazine with his piece on contemporary film culture in Vogue. The article has the titillating title ‘More Skin, More Everything in Movies’ but, despite reader expectations, Alloway is not particularly interested in cinema’s new permissiveness. His real focus is on film’s binary status as a work of art and a commercial product. His motive for discussing the Sinatra movie, Tony Rome, and the Warhol film, The Nude Restaurant, both made in 1967, is to provide an account of contemporary film culture. Following an introduction about his experience of attending an early morning screening of the Sinatra movie in an ‘elegant’ Times Square theatre and then, in the evening, just a few blocks away, seeing the Warhol film in a ‘grim movie house violently converted from an elegant legitimate theatre’, Alloway sets up his line of enquiry:

These two films are about as unlike as any pair you could take. The first is a polished Hollywood movie with a curious sense of time; it is new but it seems old. It is a revival of a convention that was at its strongest in the forties and fifties – the private detective story. The Nude Restaurant, on the contrary, looks familiar – like an exploitation film – but is, in fact, new. What is the situation that puts both films in the same town at the same time? Do we have to choose between them, or is some kind of unifying theory possible?7

The choice is between art and commerce, which had been complicated by the changes in film production and exhibition. Alloway considers this choice within the context of the collapse of a universal audience, the ideal that Hollywood so assiduously appealed to during the heyday of the studio system. Hollywood had once striven to make films that were acceptable to one and all, regardless of age, gender and class, but in the late 1960s films had to work in a market of ‘distinct and irreconcilable layers of taste’8 The ‘universal’ had become the province of television. Alloway explained this shift in terms of the film industry moving into a mature phase, as the automobile industry had done earlier. Linking the movies to car design, Alloway argued that the ‘annual style changes were sufficient to entertain us with a comedy of newness but not radical enough to disrupt continuity with earlier models’.9 Production techniques were advanced and flexible enough to offer diverse products, that is to say choice to the consumer, without compromising mass production. ‘This was the reverse of what both leftwing and nostalgic critics of industrialism had predicted’, which was ‘a life of monotony and repetition’.10 This is an intriguing line of reasoning, though recent historical work suggests diversity in the film industry was principally caused by the government’s anti-trust policies, which forced the oligopolistic studios in 1948 to break up their holdings in production, distribution and exhibition. This shift in the industry allowed more competition from an ever-increasing independent production sector and from films imported from Europe.11

Whatever the causes of diversification, as Alloway pointed out, even highly esoteric films produced on zero budgets, such as Michael Kuchar’s Sins of the Fleshapoids (1965) or his twin brother George’s Hold Me While I’m Naked (1966), could now be seen in public theatres. New, cheap, lightweight filmmaking technology made it possible to produce ‘a personally expressive cinema without collaboration, without conferences’.12 And this, Alloway divines, is most apparent in these films’ permissive representation of sexuality and nudity; a filmic fixation that was also shared by many contemporary mainstream films in the post-production code era of self-censorship and before the new era of film classification (which, from 1967 onwards, restricted access to movies with adult topics). In this context of production and exhibition, the distinction between art and entertainment was diminished, at least at the level of the pursuit of more nudity, more sex.

The distinction between the fine and popular arts was also being undermined by the rage for identifying individual agency in the creation of commonplace films. Alloway rejected the critical vogue for auteurist theory that assigned artistic achievement within Hollywood productions to the director (for example, Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks, Budd Boetticher and Samuel Fuller), and instead explored the ‘conventions that shape films regardless of the director’s identity and thematic preoccupations that run from one film to another’.13 And shifts in a convention, he argued, ‘can be as expressive as an individual’s invention, provided you are informed about the conventions’.14 Critics, who bring to film an expertise based on contemplative analysis of the fine arts, misunderstand or ignore the role of convention, but not so regular filmgoers. In the post-studio context of film production, where films are targeted at specialist and niche audiences, the habitual consumer of films is conceived as an expert, or at least an enthusiast, familiar with conventions and therefore able to recognise, work with, and interpret even a minor change in form or style.

Following the widespread acceptance of auteurism as a legitimate critical practice, film scholars, cognisant of the fact that this form of analysis obscured a wider understanding of American movies, turned to genre theory as a guide to Hollywood’s productions. However, just as he had ignored auteurism, Alloway also ignored the critical turn to genre studies. Instead, he recorded and commented upon the process of repetition marked by incremental innovation or readjustment in clusters of films; rather than the isolated film as focus, or the predefined generic ideal, Alloway examined films in terms of sets and runs, producing a study of temporally defined groupings of films. As in genre theory, the object of his attention was to consider a film’s commonality with other films. This commonality was considered not just through content, form and style, but also through enquiries into production, distribution and the consumption of repeatable experiences. Films in an identified cluster might belong to a single genre, the western for example, but they might also be made up of a diverse range of generic types, mixing elements of the gangster, war, musical and western film. The most commonly used term deployed by Alloway to describe these clusters of films was a ‘cycle’.

A cycle is a series, run or set of successive and related films that are produced over a measurable period of time, the duration of which is marked from a beginning, through development and productivity, to dissipation, fade and ending. With the study of cyclical production, the objective was to set aside the unique, the extraordinary and the distinct, films removed from history, and instead turn to recurrence, overlap and fusion, which form the associations that create the liaisons and connections within and between cycles. This produced a more complete understanding of film production trends than could be achieved by traditional genre analysis, because cycles are inherently historical and mutable, while genres tend to be conceived as ahistorical and essentially unchanging.

Genre theory often presupposes that films belong to exclusive fixed groupings, which can be readily conceived as existing outside of time. The concept of cycles, however, is fixed inside time. The study of cyclical productions allows for both the recognition and identification of films with shared characteristics, and also enables the scholar to see how a cycle merges and blends with other cycles. The scholar thus becomes interested in film’s inherent seriality, with its dual focus on reiteration and modification, or stasis and change. This process of the production of repetition and difference (a specificity film shares with other popular arts) is located within a historical continuum, which is sensitive to the conjunctures between film and the social order. Cycles belong to history.

The study of film cycles reveals uniqueness to be little more than a re-articulation of existent components. However, the form, style and content of films do change over time. Documenting and analysing cycles of films, while being cognisant of shifts in social contexts, and in the production, distribution, exhibition and reception of films, can help account for these changes. Film, Alloway argues, unlike non-mechanised art forms, is adaptive; it changes to meet the needs of its audience. It shifts with the impact of new technologies, conforms to new exhibition practices, and absorbs the influence of competing media. For Alloway, film’s ability to adapt to new situations is what defines it; the movies are ‘part of our general communications system, in a way that painting and sculpture, for instance, are not. Movies have topical links to our environment, the styles that we identify ourselves by, because these are the subject of the camera’.15 This is what links, despite their marked differences, the Warhol and Sinatra pictures. Both films are recordings, documents, indices of the now. The films are highly topical, Alloway argues, in the manner in which they act as guides to life, measures of potential lives and of the consumer choices we face or desire.

As much as runs of films can act as indices of shifts in the production and consumption contexts of movies, they can also make legible the time in which the films were produced and consumed. A study of film cycles is therefore also a study of the topical nature of film. This is a form of analysis that can elucidate film’s connection to the everyday without resorting to vague notions, such as a Zeitgeist, or to general symptomatic readings to explain the changes in what was watched and the way people lived.

As the film historian Gregory A. Waller has noted, topicality ‘is elusive and conjectural, but it cannot be ignored, especially when it comes to films designed for the commercial marketplace, where the topical is a significant attraction, a source of pleasure and a reminder of the ties that link the screen to the discourses that circulate in and comprise the public sphere’.16 To chart and identify patterns of recurrence and change in the movies, to consider production cycles and their mutual relationship with topical issues of the day enables the scholar to arrive at an opinion that is verifiable against the evidence mustered before the reader. Too often, Alloway argued, critics ‘dismiss as aesthetically negligible a formulaic film that may be an interesting, valid, even original development within the convention. Internal successive modification of forms … is a governing principle of popular culture’.17

An examination of film cycles allows for a particularly responsive account of small but significant shifts in how Hollywood conceived, produced, distributed and exhibited its films. Thinking about films in terms of genres, directors or stars tends to favour similarity in productions over and above difference. In genre studies the critic searches for an ideal, in star studies he or she attempts to define a paradigmatic performance, while the auteurist critic looks for the repetition of motifs to link together often highly disparate films. On the other hand, the critical study of cycles does not privilege repetition over novelty, stasis over change, but instead seeks to examine and explain patterns of reiteration alongside innovation. Conventions are never entirely fixed, but mutable. A generic ideal can never be realised, only imagined. As Alloway noted, ‘One of the dangers of genre theory is that the categories may be taken rigidly. When that happens they lose their descriptive usefulness and assume normative function’.18 Genre theory frequently articulates a desire for stability where none exists. Films are fugitive, not captive.

Reyner Banham wrote that in ‘engineering a standardised product is essentially a norm, stabilised only for the moment, the very opposite of an ideal because it is a compromise between possible production and possible further development into a new and more desirable norm’.19 The industrial art of Hollywood is based upon the fetish of the norm, its confirmation and disavowal. Change and stasis, or novelty masquerading as innovation, characterise Hollywood’s film production. But, just as in car design, films do change over time, however incrementally and hesitantly those shifts are realised.

As an example of this modification of conventions, Alloway considered The Wild Angels and the emerging cycle of motorcycle-gang films. He compared these to their precursor, The Wild One (1953), noting how that film had the outlaw bikers ride toward fixed cameras, while the contemporary films use mobile cameras. In the former the ‘camera’s point of view is separated from that of the intruders’, in the latter the point of view is the gang’s: ‘By matching the riders’ speed the camera shows them, in fact, using the highway like a room, relaxing, talking, drinking as they go. Only the background moves.’20 This paradoxical image of domesticated outlaws, in movement, but somehow static, a fantasy of contained rebellion, is as astute a comment that ever was made on a group of films which have never been on the agenda of film studies, and I doubt were ever again mentioned in Vogue. Alloway concluded by contrasting the lead actor Marlon Brando’s outlaw figure – inspired by the French actor Jean Gabin’s tough but melancholic characters – and the protagonists of the new cycle, who are ‘presented in a detached, statistical spirit’. In an earlier review of The Wild Angels he noted that, compared to The Wild One, the protagonists’ motivations were negligible, not much more than ‘statements or actions, not as sequences or developments’. As such, he surmised, motivation in the film is equivalent to that found in pop songs on 45 rpm records, which have typical rather than personal referents. Motivations become personal only to the extent to which they ‘touch on our statistically shared rather than our private roles’.21 That is, popular culture is linked to our own lives through the personal characterised in statistical terms – the individual defined, in contradiction, by his or her resemblance to those who form a crowd.

One determinant of change is the need for productions to respond to topical issues and to maintain a dialogue with contemporary culture through the incorporation of everyday objects into a film’s mise en scène. Hairstyles, the cut of a jacket, the line of a coat, the model of automobile, street furniture, branded goods, all help to signify a film’s contemporaneity. As much as Hollywood drives fashion changes (magazine spreads on the latest styles of handbags carried by film stars, for example) it is also at the mercy of fads, vogues and seasonal changes. This is why movies, regardless of developments in technology, fast become dated. Though all films are caught up in the imperative to keep up to date, some are more highly marked by a link to contemporary material culture. This is the point that Alloway was making when, through the prism of The Wild Angels, he looked at the shifting meaning of Nazi regalia, which is heavily featured in the film. He notes that the only helmets worn in The Wild One were World War II-style ‘Nazi coal-buckets’, and these are also present in Corman’s film. The bikers in The Wild Angels, however, also wear a range of Nazi insignia, including iron crosses, and a large Swastika flag is prominently displayed during the culminating funeral meeting and procession. Alloway writes:

The point is made early in the movie that a Nazi emblem is ‘garbage’ to somebody old enough to have killed its original wearers in World War II. Now, however, the once-loaded symbol has been separated from its caste functions via the intervening comics and movies about ‘good’ Germans. The deadly symbol becomes optional ornament. Its World War II significance is almost a lost language as it is incorporated into a style of personal adornment … Like classical ornament which descended from temples to fireplaces, from Triumphal Arches to dressing rooms, in 18th-century architecture, the Swastika and the non-Christian Maltese cross are general again, like the ‘S’ on Superman’s chest, like two-image Batman rings.22

The artist, sociologist and member of the IG, John McHale noted that the new media landscape of the 1950s represented an acceleration of everyday life which required ‘an array of symbolic images of man which will match up to the requirements of constant change, fleeting impression, and a high rate of obsolescence. A replaceable, expendable series of icons’.23 Echoing McHale, Alloway wrote that the movies produce a great awareness of the ‘dimensions of living’ but also amplifying those dimensions so that American life takes on the appearance of a ‘drag strip of hotted-up crisis … This aggrandised present induces anxiety partly because, by a curious twist, American practicality, the ethic that something can always be done, gives equal urgency to both marginal and central problems. The mass media’s social effects have been subject to such a process of intensification’.24 In Alloway’s view, this is less a moral problem than a causal effect of conservative forms and technological innovation that is most ‘fully visualised and articulate when the subject is violent’.25

Violence in America’s movies became Alloway’s focus. Towards the end of his piece in Vogue he introduces the forthcoming series of film shows at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, that he had programmed. The series examines ‘the themes and conventions common to groups and cycles of films’ which are ‘intended to reveal some of the characteristic patterns of cinema’.26 The programme of action movies mapped violence as ‘the recurring and typical element’ of certain film cycles produced between 1946 and 1964. Alloway’s project begins with film’s topographical and sociological terrain, particularly its indexical rendering of highly topical or public affairs content.27 Films are shaped, he argued, by contemporary events, the war in Korea for example, but the war alone does not account for the general tolerance of violence in the movies. It is a movie’s conventions that govern the heightened use of violence in certain situations because it enables an expedient solution to any given problem: ‘Violence as motivation gives the maximum definition to a story.’28 This is necessarily so in movies which are averse to producing long and complex explanations for any given dramatic situation. Because film violence is conventionalised it is generally unremarkable. However, as conventions mutate, change makes the representation of violence remarkable. The critical furore that blew up around Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) is a good example of this process. Peckinpah’s use of slow motion drew attention to the impact of projectiles on bodies, unsettling spectators who had become complaisant about violence in Westerns, but this innovation soon became a stylistic trope, something expected in a Peckinpah film. Once audiences have absorbed the novelty of representational shifts they become the new conventions.

Representations of violence are tied not only to cycles of innovation and convention, but also to topical concerns. Alloway wrote: ‘At the movies it is the recognition of topical material within traditional forms, the capacity of the norm to absorb new elements, that is a particular pleasure’.29 Considering the shifts in cycles of action movies before and after World War II, he noted a variety of factors at play, probably the diffusion of a more dogmatic scepticism, the popularisation of psychoanalysis and vernacular existentialism that ‘turned the prewar action film (basically athletic and cheerful) into the more savage, more pessimistic film of violence with its gallery of extreme situations and desperate heroes’.30 Post-war audiences became accustomed to the ‘spectacle of violence and death in a context of psychic depth, institutional doubt, and existential solitude’.31 Violence in the movies was presented as a drama of ‘social risk’.32

As the movies dramatise risk defined by the topical, so movie producers look to proven formulas as a base for these stories. Alloway argued that in predicting what an imagined future audience would want to see, movie producers ‘have to extrapolate present successes into probable future trends, and you must protect your film against obsolescence during production’.33 Obsolescence, however, was also a fact of film. Movies rapidly disappear from view when the audience turns to new attractions, but the expendability of films was compensated for by the prolongation of ideas and the durability of conventions in film after film.34 The temporal span of an individual movie’s existence, or the duration of a film cycle – its ‘usability’ – was thus a principal of Alloway’s criticism: ‘Thinking in terms of a time scale for art forms makes it possible to take ephemeral art as seriously as the presumptively permanent.’35 The fugitive nature of individual films, the cumulative span of the films that form a cycle, and the long duration of a film trend that is formed from film cycles, are the basic temporal units that Alloway identified and examined.

Alloway’s theory enables an examination of a film’s commonality with other films. This commonality is considered not only in terms of content, form and style, but also through enquiries into production, distribution, reception and the consumption of repeatable experiences. In addressing vital questions about the formulaic nature of film, he proceeds from the understanding that film is a popular art and it is also an industrial art. The terms of his enquiry are thus framed by an investigation into the contradiction between film as a manufactured, standardised, product and film as an art form and practice. Films recycle themselves; stories, formal elements, characters and so forth are defined through recurrence, but the process of reiteration is always open to modification. Conventions are not immutable; they are susceptible to augmentation. The challenge Alloway poses is to understand this unstable combination of repetition and difference. In sum, his film criticism explores the oxymoronic concept of the production of regular novelties.36