David Hockney’s A Rake’s Progress was published and exhibited in late 1963, little over a year after his graduation from the Royal College of Art.1 The sixteen etchings projected a singular artistic persona: witty, charming, youthful, frankly homosexual, and possessed of technical virtuosity and inventiveness allied to a knowing immersion in tradition made explicit in the allusion to William Hogarth’s graphic cycle of the same title. However, the appeal of A Rake’s Progress resided not merely in Hockney’s precocious assurance but also in his chosen subject-matter of the artist’s adventures in New York City. In that sense, the work spoke to an infatuation with all things American then pervasive in British culture and society.2 The writer Malcolm Bradbury remarked of the years on either side of 1960 that ‘it was a time when Americanization was passing through Europe like … a dose of salts’:

America was where, it seemed, everything that was best came from – the best jazz, the best novels, the best ice-cream, the best cars, the best films. I became a typical example of a constant figure of the time, Midatlantic Man … In Britain he talked all the time of the States; in America he would become notably more British, a flagship in his Harris tweeds … And America proved pretty much what was expected. After austerity Britain, it was wildly exciting.3

Hockney’s own first visit to America ‘was something very special to me’, and the prelude to a lifetime of moving between the two countries.4 Prizes and sales of works meant that he could contemplate an extended stay in the summer of 1961. Hockney had personal motivations, over and above the general climate. As a homosexual, he would have been well aware that such figures as Cecil Beaton, W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood had submitted to the lure of America.5 Equally, as abstract expressionism was all the rage, trips to New York had become a rite of passage for progressive-minded students at the Royal College of Art, the equivalent to the cultural pilgrimages that former generations had made to France or Italy. Indeed, the availability of modestly priced air tickets in 1961 encouraged a number of Hockney’s contemporaries to make the trip, including the graphic design student Billy Apple, with whom Hockney travelled and occasionally met up in New York, as well as his friend Brian Haynes, current art editor of the Royal College of Art magazine ARK.6 The following year Haynes published photographs he had taken in New York, accompanying an essay which asserted that the city and country had both lived up to and undermined his expectations of ‘the promised land’: ‘They were so much more developed than us … The billboards were amazing.’ But there were also drunks lying in the street in the Bowery district, and heading south and seeing whites and blacks entering the bus through different doors ‘was the beginning of a naive sort of social awareness on my part’.7 Beaton had been struck by such contrasts before the war, while in interviews Hockney also recorded comparable reactions to the spectacle of poverty and discrimination. Indeed, he recalled that it was the squalor in areas like the Bowery, with people sleeping on the streets, that prompted the idea of reinventing the Rake’s Progress narrative in a contemporary context: ‘I saw this and I thought this is like eighteenth-century London – it’s Hogarthian.’8

Hockney’s A Rake’s Progress tends to be understood in somewhat literal terms as a record and celebration of that mind-opening visit. In David Hockney by David Hockney (1975), the artist remarked: ‘when I came back I decided to do A Rake’s Progress because this was a way of telling a story about New York and my experience and everything’.9 Subservience to the horse’s mouth in subsequent literature has inhibited analysis of the complex thought processes and allusions that, in reality, underpinned Hockney’s sophisticated art. There has been little informed speculation to date about how and why he chose the particular subjects that made up the eventual series, and arrived at the decisions he did regarding medium, format and idiom. One important factor, I shall argue, was an alert responsiveness to the cultural environment in which he found himself, which also looked to America for inspiration. Commentators have emphasised that, on one level, the project was bound up with Hockney’s self-projection as a homosexual, already a theme of paintings produced at the Royal College of Art in the privacy of his studio space. Specifically, I want to present Hockney as recapitulating, knowingly or otherwise, what has come to be seen as a ‘queering’ inherent in the embrace of ‘trivial’ discourses of gossip and camp talk within avant-garde literary and aesthetic practice, a process exemplified by figures active in New York during the late 1950s such as the poet Frank O’Hara and artists like Larry Rivers and Jasper Johns, who were at the forefront of the revolt against abstract expressionism and its macho aura.10

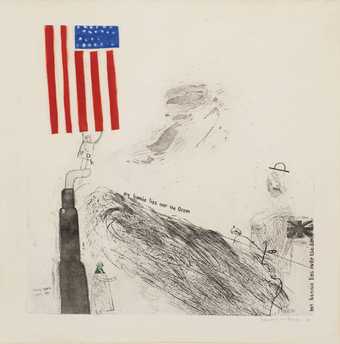

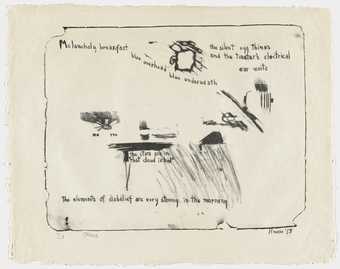

We shall return in due course to A Rake’s Progress, but to help establish an appropriate framework for making sense of the series, I want first to juxtapose two other prints that likewise bear on matters of transatlantic dialogue and artistic identity. One is Hockney’s My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean, inscribed ‘July 1961’ (fig.1), the other ‘Melancholy Breakfast’ (fig.2) from the portfolio entitled Stones, which had been created a year or two earlier as a collaboration between the aforementioned New York School poet Frank O’Hara and his close artist friend (and sometime lover) Larry Rivers. The former is an etching, combining fine line with tonal blocks and marks using aquatint, including the insertion of colour in the Stars and Stripes. ‘Melancholy Breakfast’ is a monochrome lithograph, employing a softer, more crayon-like method. The allusion to a traditional British folk song in the Hockney contrasts with the purely personal and poetic content of the American work. Nevertheless, there are several striking affinities, including the integrated lines of hand-written text, sometimes floated at eccentric angles; the passages of dense scribbling located towards the bottom centre of each image; a general effect of improvisation and of pockets of artistic incident, from legibly figurative to abstract, dispersed as if randomly within the compositions. Such parallels might be regarded as coincidental, the outcome of two artists seeking to extend the informal look that had been developed within abstract expressionism, and extended into more figurative idioms by subsequent generations of American artists (a figure like Robert Rauschenberg springs to mind). But can we see the similarities between the two prints as symptomatic of a wider cultural engagement on Hockney’s part?

My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean happens to be the first known work that Hockney created on American soil. We know very little, in truth, about his activities that summer, beyond the episodes recounted with hindsight in A Rake’s Progress in 1963. He met up with Apple and possibly other Royal College of Art students, but his main contact across the pond was Mark Berger, an American friend from the painting school who, along with R.B. Kitaj, had doubtless encouraged Hockney to make the trip, offering to keep him company and show him around. In his autobiography Hockney mentioned Berger only once, noting that, when he first visited New York, Berger was the only person he knew, but ‘was in hospital with hepatitis all the time I was there’.11 In fact, Hockney stayed with Berger at the latter’s parents’ house in Long Island, soon after arriving and before the onset of his friend’s illness. Hockney reported to his family early on that he had plans to visit New Orleans and elsewhere in the south.12 It is likely that he and Berger were contemplating making the trip together, given that the latter had been teaching at Tulane University in New Orleans before taking the year off to study in Europe.13 Presumably the hepatitis prevented this expedition, with the consequence that Hockney decided to remain in the north-east. From biographies we also gather that it was through Berger, during that visit to Long Island, that Hockney met another young artist, Ferrill Amacker.14 The two men hit it off, and Hockney ended up spending the rest of his trip sharing Amacker’s well-appointed apartment in Brooklyn Heights, in an occasional sexual relationship. They engaged more widely with New York’s gay subculture, which clearly seemed a good deal more exciting and developed than its London counterpart.15 It is curious that Hockney’s account should simply have stated: ‘I met a boy in a drugstore in Times Square and stayed with him for three [sic] months’.16 This brings home the selectiveness of David Hockney by David Hockney, comprising as it did what he remembered and chose to recall some ten years after the event.

Hockney’s immediate reactions are conveyed in the odd surviving letter back home, composed during the early part of his trip. His camp humour and sense of Britishness come through in an epistle to American Kitaj (‘Ron – old chap’), who had evidently commissioned him to purchase a book, magazine and pair of trousers. After reporting on such practicalities, Hockney declared:

I like this town – vegetarian restaurants on every corner. I haven’t been in the Empire State Building yet – but I wouldn’t be surprised if the whole of that wasn’t one big Veg. restaurant. The funny thing is that New Yorkers don’t look like animal lovers.

‘Il Marko’ [Mark Berger] is convalescing at home now (he only came out of hospital on Friday) and at the moment I am staying in Brooklyn – with an awfully nice fellow, and doing a bit of etching at a place near here.17

The last point is picked up in a more formal communication dispatched to his prospective dealer, still ‘Mr Kasmin’:

I’m having quite a time here, although the weather is uncomfortable (it seems to be permanently over 70 degrees).

The Museum of Modern Art here have bought two of my prints – and I have been doing a bit of work at the Pratt Institute. I hope to start some painting next week – unless I go west to California.18

It did not take Hockney long to descend upon the Pratt Institute, conveniently located near Amacker’s apartment, and to produce My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean. The trip to California did not, of course, happen at this stage, although it is interesting that he already had the idea in mind, inspired by the movies and by issues of Physique Pictorial magazine that Berger had brought with him to London. There is no evidence of any paintings having been realised in the US, but it might be said that one catalyst for My Bonnie was Hockney finding himself with more time on his hands in New York than he had anticipated. He clearly experienced a powerful compulsion to work, and not just to spend his time being an idle tourist. Printmaking must have seemed a more practical option than having to deal with the transportation of canvasses. He had recently revived this interest back at the Royal College of Art, on running out of money to buy painting materials.19 Beyond the artistic satisfactions that the medium provided, Hockney found that he could readily sell prints, both in London at the St George’s Gallery and then again in New York, where he made contact with the curator William Liebermann, who purchased works for the Museum of Modern Art and advised Hockney about other possible purchasers.20 Conceivably, one motivation for producing My Bonnie was generating sales to subsidise his trip. The imagery, and the charm and humour of the treatment, seem calculated to appeal to collectors on both sides of the Atlantic.

Hockney’s choice of theme is interesting given the currency of the folk song. An instrumental version by Duane Eddy was a hit on both sides of the Atlantic in 1960. Moreover, just a few weeks before Hockney set to work, My Bonnie was recorded in Hamburg by Tony Sheridan, on vocal and lead guitar, with backing from ‘Die Beat’ Brothers, whose first ever recording this was.21 By the time the song was released in England in July, the band had reverted to calling themselves The Beatles. Perhaps the general revival of the song was connected not just to the folk revival but also to the burgeoning of transatlantic travel and cultural transmission at this time. But Hockney certainly made the theme his own. Alongside its light-hearted whimsy, his composition presents a distinctive fusion of nostalgia and desire, in both content and artistic language. The title of the traditional song hovers above the scribbled indication of the Atlantic Ocean, with stormy clouds floating above, whose vast expanse separates Hockney’s own new and old worlds. On the left-hand side, the artist (‘DH’) stands atop a vertical structure, recalling at once the kind of extractor flues that one might encounter on a New York rooftop and, on a different scale, a schematic, ziggurat-like skyscraper along the lines of the Empire State Building, as viewed perhaps from the distance of Brooklyn Heights. The figure holds aloft the gigantic, coloured Stars and Stripes, as if to signify the fantasy of a King Kong-like conquest of America, while down below we encounter the date, July 1961, and a figure of George Washington incorporating a collaged head extracted from a US postage stamp. The figure seems to gesture in a friendly manner towards the old colonial power and sometime enemy, and the reference to the stamp signifies the means by which Hockney and antryone else could keep in touch with family and friends back home. To the right of the composition we see a more complex montage of overlapping elements, a small black and white Union Jack, whose pole is another, vertical version of the title slogan; a simplified figure sporting a hat; another figure (‘P’) waving another Union Jack; and an idealised, classicising profile that may signify the young man identified by a further, larger ‘P’ (presumably Peter Crutch, with whom Hockney was currently infatuated). We might take this whole passage to evoke memories of the beloved ‘bonnie’, back in London, who was still on Hockney’s mind that summer, even as he took in the heady excitements of New York.

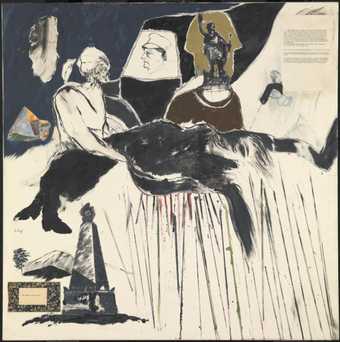

Fig.3

R.B. Kitaj

The Murder of Rosa Luxemburg 1960

Tate T03082

In metaphorical terms, the particular romantic attachment may stand for a more general allegiance to his homeland, from which he felt unable or perhaps unwilling entirely to escape, while coming to terms with such a different environment. One might see some such attitude as implicit in his decision to tackle this traditionally British folk theme in a print made in the USA. But another reading would be to interpret Hockney’s ‘bonnie’ as in fact America itself, understood not nostalgically but rather as the object of his imaginative yearning (in full technicolour), now indeed attained, an earthly paradise from the perspective of dull, self-satisfied, black and white England. The phrase can be taken, in other words, to signify in those two distinct ways, looking backwards and forwards, just as it occurs twice in the image itself. Hockney, we might say, was channelling into this modest-looking work quite complex and ambivalent feelings about his own personal and artistic identity, and the mingling in his own mind of nostalgia and the urge to embrace new possibilities. In relation to art, the inclusion of a ‘found’ image brings to mind current work on paper by Rauschenberg, in which elements of mass media imagery, inserted by means of solvent transfer, are combined with rough mark-making and informal, all-over compositional effects. However, Rauschenberg’s aesthetic had already been mediated for Hockney by the example of Kitaj. In My Bonnie the montage structure, combination of image and text, and interweaving of careful delineation with seemingly random, graffiti-like marks seem closely modelled on recent pictures by Kitaj that he would have known well, such as The Murder of Rosa Luxembourg 1960 (Tate T03082; fig.3).

But American points of affinity emerge if we take account of the immediate circumstances of the work’s creation in Brooklyn. It was Liebermann who evidently advised Hockney to make contact with the Pratt Institute.22 But the college had a good deal more to offer than equipment and convenient location. The Pratt Graphic Art Center had been established in the mid-1950s and played an important role in the revival of American printmaking that came fully to fruition in the 1960s. It provided artists drawn to the format with both studio and exhibiting facilities.23 Hence, figures like the young Claes Oldenburg and Jim Dine, as well as abstract expressionists Robert Motherwell and Barnett Newman, made productive use of the workshops. It was at Pratt in 1961, for example, that Dine produced These Are Ten Useful Objects Which No One Should Be Without When Traveling, a portfolio of ten drypoints, while Oldenburg created a poster for his Store exhibition as well as other prints, and Newman a significant series of abstract lithographs. Hockney found himself operating in not just any old art college environment but rather in one of the most sophisticated centres for printmaking currently available in an American or indeed international context, a facility which probably made the Royal College of Art in London seem old-fashioned. From looking at what was going on around him, and talking to individuals he encountered at Pratt, he would surely have learnt a great deal about the position of the print within the American art world.

He is likely to have become familiar there with the graphic activities of Larry Rivers, an artist generally much admired in British art college circles in the early 1960s, in whose work Hockney may well have been interested even before travelling to New York. It is interesting to note that when Hockney drew a portrait of Berger during his visit to Long Island, it was against a backdrop of Camel cigarettes imagery.24 This was a favourite Rivers theme in the early 1960s, and perhaps the implication was that Berger was a fan, who had transmitted his enthusiasm to Hockney. Aside from his paintings, Rivers could have benefited, in Hockney’s eyes, from his close links with writers. In 1960, for instance, Jack Kerouac’s Lonesome Traveller book of essays appeared with a cover and illustrations by Rivers.25 That same year the artist worked with Kenneth Koch on a series of poem-paintings, involving a visual interplay between gestural marks, imagery and hand-written verse. Above all, Rivers was known for his long-standing collaborative relationship with Frank O’Hara, starting with the frontispiece for A City Winter and Other Poems (1952). It was O’Hara who contributed the text about Rivers for Martin Friedman’s School of New York: Some Younger Artists volume, published in London in 1959.26 But their best-known and most fully realised example of interaction across visual and verbal media was, of course, Stones, the sequence of thirteen lithographic prints interweaving passages of poetry hand-written (using a mirror!) by O’Hara and pockets of imagery and abstract design contributed by Rivers. Stones was executed in an intensive, improvised manner over 1957–8 and finally published in 1959 by Tanya Grossman’s Universal Art Editions.27 It is plausible to suppose that the affinity with which I began, between My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean and ‘Melancholy Breakfast’, reflected Hockney’s awareness of this recent, notably ambitious print project. We might note that the second plate in Stones is headed ‘Love’ and includes a lyrical poem and suitable graphic accompaniment. ‘Love’ was likewise one of the first words Hockney included in otherwise abstract paintings of 1960, and a theme of several works from that year.28

The parallels with Stones open up the possibility that Hockney took an informed interest in the New York poetry scene. He was, after all, a well-read and self-consciously literary artist, using written components in many paintings to embed references to the likes of William Blake, Walt Whitman, Auden and Constantine Cavafy.29 An engagement with literature was one of the things he found he had in common with Kitaj.30 Did this extend, in both of their cases, to contemporary American literature? But we should note the significant impact exerted in the UK by Donald Allen’s 1960 anthology The New American Poetry, featuring the Beat poets such as Allan Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, along with Charles Olson, Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery and many other emerging figures, whose work had been little known hitherto in Britain.31 Produced in San Francisco, Evergreen Review was another cult publication, combining artistic and poetic content, which seems to have been avidly consumed in Britain. This phenomenon in literary transmission exactly parallels the availability and inspiration of recent American painting and sculpture, a narrative familiar to historians of British art of the period.

It is feasible, then, that Hockney already had a nascent interest in American literature when he arrived in New York, but he recalled being excited by the bookstores there, which stayed open all night and where one could browse at leisure.32 We might imagine him absorbing the latest issue of Evergreen Review, featuring an account of the seamy homosexual subculture in New York from John Rechy’s forthcoming novel (City of Night, published in 1963, which subsequently inspired Hockney’s first trip to Los Angeles).33 There was also the wonderfully camp and irreverent text ‘How to Proceed in the Arts: A Detailed Study of the Creative Act’, another collaboration between O’Hara and Rivers.34 At any rate, My Bonnie offers an intriguing visual equivalent to the casual, affectionate, nostalgic tone, combining tender lyric sentiment with mundane circumstances, that O’Hara deployed, for instance, in his recent poem ‘Song’, first published in the same year of 1961.35 Likewise, it seems a short step to Hockney’s The Cha Cha Cha that was Danced in the Early Hours of 24th March 1961, based on memories of watching Peter Crutch dancing at a Royal College of Art ball, from one of O’Hara’s poems about having a good time in ‘The Old Place’, the gay bar in Greenwich Village after which the poem is named, in the company of fellow poet John Ashbery: ‘Down the dark stairs drifts the steaming cha-cha-cha./ thThrough the urine and smoke we charge to the floor./ Wrapped in Ashes’ arms I glide.’36

There were two obvious reasons why Hockney would have been familiar with O’Hara. One was his status in the art community not just for his poetry but rather for his activities and publications as a rising curator at the Museum of Modern Art, and as the author of the first book about Jackson Pollock (1959), plus many other articles and artist interviews.37 The second was the poet’s sexuality. Given Hockney’s personal contacts in New York and therefore access to gossip, which, according to Gavin Butt, was an activity of special importance within the gay community in a period when homosexuality was illegal, it is very likely that he would have become aware of O’Hara’s credentials and status as a gay man, whose sexuality perhaps conditioned the ‘camp’ idiom and rejection of macho posturing characteristic of his poetry from the second half of the 1950s onwards.38 This perspective has become a strong theme in recent literature on the poet’s work, though its earlier absence did not mean sexuality was not talked about and celebrated in a sub-cultural context (as it surely was, back in London, with regard particularly to the painter Francis Bacon).

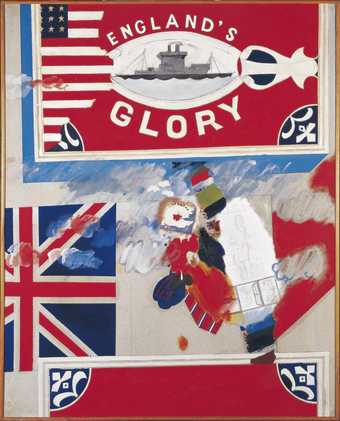

Fig.4

Derek Boshier

England’s Glory 1961–2

Museum Sztuki, Lodz

If there is a single contemporary British work that shares the thematic and artistic concerns of My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean, it is the painting England’s Glory (1961; fig.4) by Derek Boshier. Across the media divide, affinities between the two images include the incorporation of both British and American flags, and a suggestion of interchange across a watery expanse; the fusion of such bold, colourful, geometric elements with montage-like passages of more complex and fluid imagery, and with gestural marks; the incorporation of words on a variety of scales; and an overall informality and visual congestion of pictorial structure. The Boshier painting has been discussed in relation to the currency in his early work of the theme of ‘American influence and, most especially, American corporate and military power’.39 Here, the demise of British imperial power is intimated through the American flag eating into ‘England’s Glory’ (evoking the title and design of a well-known British box of matches) and the storm clouds beginning to eclipse the large Union Jack, while a strip of smaller ones are more fully buried beneath the jumble of elements including abstract marks but also imprinted advertising imagery, a map showing the potential impact of a nuclear bomb targeting central London, flags evoking the current process of decolonisation, and additional reminders of a historical legacy increasingly losing its relevance, such as a tie (suggesting the world of public schools, gentlemen’s clubs and military regiments), as well as Nelson’s famous slogan: ‘England expects every man to do his duty.’ Boshier, one might say, was revisiting the tradition of landscape painting (England’s glory in another sense), but the atmosphere he was registering was the metaphorical one of swift-moving historical change, with the imperial legacy ending up as little more than the nostalgic branding on a matchbox.

The approach in this painting is sociological and political, in contrast to Hockney’s private, autobiographical reflections. Boshier’s outlook reflected his immersion in recent books critical of the impact of American mass media culture, such as Marshall McLuhan’s The Mechanical Bride (1951), Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders (1957) and Daniel Boorstin’s The Image (1961).40 An ambivalence about the waxing and waning of America and Britain respectively, and about positives and negatives inherent in transatlantic exchange, doubtless featured in conversations between the two men, who were exact contemporaries at the Royal College of Art. Their close friendship and sharing of a studio is registered in the well-known photograph of the two artists standing to mock-attention next to their easels, paint brushes as surrogate rifles.41 A common artistic enthusiasm is suggested by the echoes of Larry Rivers in England’s Glory. Recent pictures by Rivers such as The Last Civil War Veteran prefigure Boshier’s fusion of heraldic flag imagery and painterly mark-making, while many other works provide a model for the inclusion of words, both stencilled and scrawled.42 While the date of My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean can be pinned down precisely, there is no documentary evidence for exactly when Boshier created England’s Glory, although the autumn term of 1961 seems most likely. Whatever the direction of interchange, however, this juxtaposition highlights a shared immersion in issues of identity, and in exploring through their work what it felt like to be British at a moment of increasing American domination, on cultural, economic, military and many other fronts.

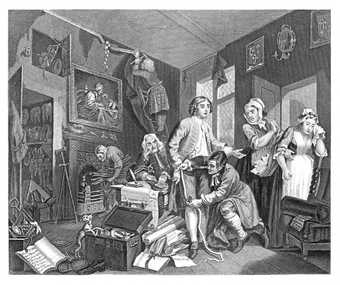

My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean established a model for the light-hearted, quasi-autobiographical mode that Hockney proceeded to elaborate in A Rake’s Progress, to which we now return. Equally, the above discussion of My Bonnie provides a template for my analysis of that more ambitious, considered and complex project. Thus, Hockney’s experiences in the US came to be presented through the filter of a cycle format and storyline modelled, as noted, on Hogarth’s eight paintings and related engravings, a quintessentially British creation.43 A Rake’s Progress was one of a cluster of projects in which the eighteenth-century artist had pioneered a genre of art depicting and commenting satirically upon the spectacle of contemporary urban life, taking advantage of the reproducibility of the print to reach mass audiences, and of the medium’s potential to project narrative across a series of intricate multi-figure compositions. It was the general and very un-modernist idea of a story developed over a series of images that evidently intrigued Hockney about the Hogarths: ‘What I liked was telling a story just visually. Hogarth’s story has no words, it’s a graphic tale. You have to interpret it all.’44

How, then, should we interpret Hockney’s synthesis of contemporary, autobiographical subject-matter and art-historical appropriation? For Philip Webb, in the first published biography of the artist, the idea was opportunistic: ‘Hockney wanted to make something effective out of the sketch-books he brought back from New York, and he hit on the brilliant idea of producing an updated version of Hogarth’s “Rake’s Progress” engravings, transferring the story of a young man’s experiences on first visiting London in the eighteenth century to New York two centuries later’.45 There was no doubt an urge on Hockney’s part to exploit the material he had brought back with him, and to tap into the wider imaginative appeal of America. But it is also worth considering whether referring back to Hogarth might also have been a means for Hockney to acknowledge and assert his own sense of British identity, not just as a tourist taking in the spectacle of America with an outsider’s detachment but also in relation to his artistic sensibility, given that Hogarth was renowned as the first British artist to assert native credentials and values, as an antidote to the general reverence for European models in the art world in which he moved. Was the Hogarthian garb an equivalent in some sense of Bradbury’s metaphorical Harris tweeds? Indeed, can we usefully consider A Rake’s Progress as one manifestation of a broader pattern of artists confronting the dilemma of ‘going modern and being British’, in the phrase coined by artist Paul Nash in the early 1930s? Does the work reflect a recurrent mechanism whereby external influences generate a perceived need among British artists to reclaim roots in the national tradition, as a strategy to secure artistic independence? This was clearly a factor, to name but two examples, in the crystallisation of vorticism in 1914, and in the emergence of a romantically-inclined, nostalgic surrealism in the work of Nash and many others in the 1930s.46

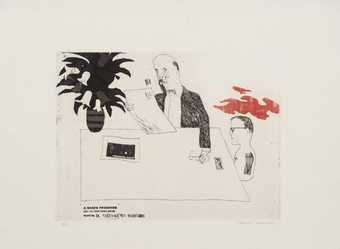

Fig.5

David Hockney

‘1. The Arrival’, from A Rake’s Progress 1961–3

Etching and aquatint on paper

Tate P07029

© David Hockney

Fig.6

David Hockney

‘1a. Receiving the Inheritance’, from A Rake’s Progress 1961–3

Etching and aquatint on paper

Tate P07030

© David Hockney

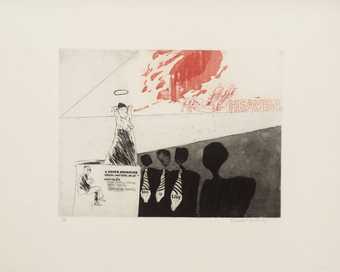

Fig.7

David Hockney

‘2a. The Gospel Singing (Good People) (Madison Square Garden)’, from A Rake’s Progress 1961–3

Etching and aquatint on paper

Tate P07032

Fig.8

David Hockney

‘3. The Start of the Spending Spree and the Door Opening for a Blonde’, from A Rake’s Progress 1961–3

Etching and aquatint on paper

Tate P07033

Fig.9

David Hockney

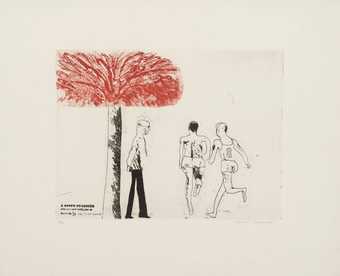

‘3a. The Seven Stone Weakling’, from A Rake’s Progress 1961–3

Etching and aquatint on paper

Tate P07034

Fig.10

David Hockney

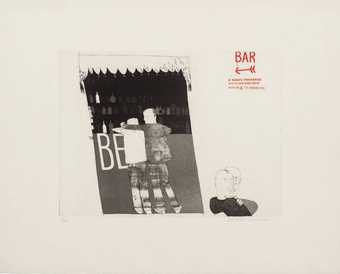

‘4. The Drinking Scene’, from A Rake’s Progress 1961–3

Etching and aquatint on paper

Tate P07035

Fig.11

David Hockney

‘5. The Election Campaign (with Dark Message)’, from A Rake’s Progress 1961–3

Etching and aquatint on paper

Tate P07037

Fig.12

David Hockney

‘5a. Viewing a Prison Scene’, from A Rake’s Progress 1961–3

Etching and aquatint on paper

Tate P07038

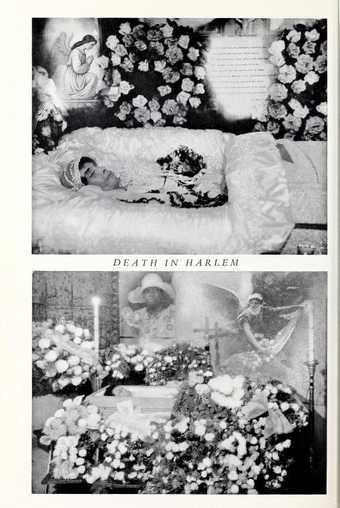

Fig.13

David Hockney

‘6. Death in Harlem’, from A Rake’s Progress 1961–3

Etching and aquatint on paper

Tate P07039

© David Hockney

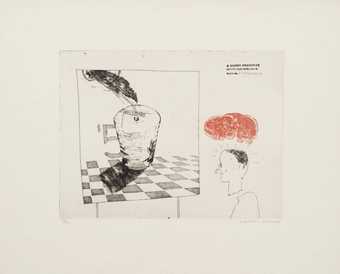

Fig.14

David Hockney

‘6a. The Wallet Begins to Empty’, from A Rake’s Progress 1961–3

Etching and aquatint on paper

Tate P07040

Fig.15

David Hockney

‘7. Disintegration’, from A Rake’s Progress 1961–3

Etching and aquatint on paper

Tate P07041

Fig.16

David Hockney

‘7a. Cast Aside’ from A Rake’s Progress 1961–3

Etching and aquatint on paper

Tate P07042

Fig.17

David Hockney

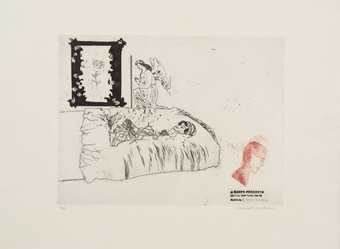

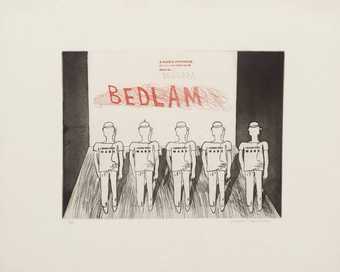

‘8a. Bedlam’, from A Rake’s Progress 1961–3

Etching and aquatint on paper

Tate P07044

© David Hockney

In Hockney’s variant on Hogarth, it is of course the artist himself, already a minor media celebrity on account of his blonde hair and stylish demeanour, who becomes the protagonist of the story, supplanting the tragic figure of Tom Rakewell, and appearing in virtually all the prints either in full figure or as a symbolic head and shoulders bust. He seems at once a specific and increasingly recognisable individual, and a more generic archetype of the Englishman abroad, wide-eyed and seeking out novel sensations and forbidden pleasures in the pleasure dome that was contemporary New York. It may be helpful, in fact, to recount the surrogate Hockney figure’s progress, or lack of it, in his imaginary rakish persona.47 In the opening image he arrives on the other side of the Atlantic, with the aeroplane on which he has travelled behind him and an archetypal (not to say phallic) pair of skyscrapers ahead, beckoning him to experience all the big city has to offer (fig.5). The artist then manages to sell some prints, after haggling over prices, which opens up the prospect of enjoying his trip even more than his initial budget had promised (fig.6). He sees some impressive presidential monuments in Washington, D.C., and attends a performance of gospel singing at Madison Square Garden (fig.7). The fifth image invokes ‘the start of the spending spree’ and a (literal) door opening for a blonde, registering Hockney’s decision to dye his hair with Clairol, having succumbed to the TV slogan ‘Blondes have more fun, doors open for a blonde’, something of an emblem of gay sexuality in post-war America (fig.8). The ‘seven stone weakling’ goes for a walk, in Central Park we might suppose, and gazes admiringly at the athletic physiques, but he seems more in his element in the next scene, where he is fraternising in a gay bar (figs.9, 10). He ‘marries an old maid’, whatever that signifies, and attends a political meeting at which the mainly black audience is being exhorted to register to vote (fig.11). In the next two images he witnesses a ‘prison scene’ in a movie, and a funeral parlour in Harlem (figs.12, 13). The final sequence records an apparent downward spiral: he is ordered to descend a metaphorical staircase as ‘the wallet begins to empty’ (fig.14); takes to drink (‘disintegration’; fig.15); finds or feels himself ‘cast aside’ (tossed into the mouth of a giant serpent; fig.16); descends yet further stairs, at the bottom of which he encounters a faceless youth with a t-shirt advertising WABC (a new, highly successful commercial radio station based in New York) and wearing headphones emanating from one of the new transistor radios; and our rake finally ends up in Bedlam, which turns out to comprise five identikit figures (with the protagonist singled out only by the small arrow above his head; fig.17). These vignettes make up a cycle corresponding, we assume, to some autobiographical narrative.

His accompanying statement, incorporated within the original portfolio, recounted the quite complicated evolution of the project:

These etchings were begun in London in September 1961 after a visit to the United States. My intention was to make eight plates, keeping the original [i.e. Hogarth’s] titles but moving the setting to New York. The Royal College on seeing me start work were anxious to extend the series with the idea of incorporating the plates in a book of reproductions to be printed by the Lion and Unicorn Press. Accordingly I set out to make twenty-four plates but later reduced the total to sixteen retaining the numbering from one to eight and most of the titles in the original tale.48

Hockney evidently embarked upon A Rake’s Progress soon after starting his final year at the Royal College of Art. It is not known if the idea came to mind even before he left America, though Hockney implies that it did in commenting, as noted, how areas such as the Bowery had struck him as ‘Hogarthian’. He later remarked that he began working on the series after completing A Grand Procession of Dignitaries in the Semi-Egyptian Style, which would place the initial phase of work in the latter weeks of 1961. Over time, however, the conception of the series underwent significant modifications, as Hockney remarked in the statement quoted earlier, which continued: ‘Altogether I made about thirty-five plates of which nineteen were abandoned so leaving these sixteen the published set. Nos.7 and 7a were etched at the Pratt Graphic Workshop in New York city in May of this year [1963], the others at the Royal College of Art from 1961 to 1963’.49 Although the prints might look at first sight like a spontaneous, diaristic exercise, Hockney devoted considerable time and effort to bringing A Rake’s Progress to resolution. The treatment of individual scenes was distilled as work proceeded over that period of eighteen months to two years. The gulf between the initial and final states of The Arrival and Start of the Spending Spree, which happen to be known, are indicative of the general shift in his artistic idiom.50 The clarity, economy and relative realism of the final works bring to mind paintings he executed in 1962 and 1963, such as Picture Emphasising Stillness and Domestic Scene: Los Angeles.51

Such stylistic modifications reinforce the point that the eventual images in A Rake’s Progress crystallised long after the events and experiences they depicted. Moreover, the series as a whole was carefully crafted, the prints possessing a notable aesthetic cohesion alongside their satisfying variety of theme and mood. Technically speaking, as in My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean, all sixteen prints combine passages of etching, played off against solid, unmodulated blocks of tone produced by the aquatint technique. A single element in each composition is printed in red, a visually arresting device. There is also a rough consistency across the plates in terms of the scale of the figures, and the visual balance between the diverse pockets of imagery that make up each scene and the expanse of blank paper. In addition to their narrative imagery, all of the final images include a prominent stamp giving the overall title, the place of execution (New York and London) and the date of the series (1961–2), with the specific title for each of the numbered plates then filled in by hand. The deliberate crudity of the stamps confers a folk art quality on the works, as opposed to the slickness and conventional signatures characteristic of fine-art printmaking.

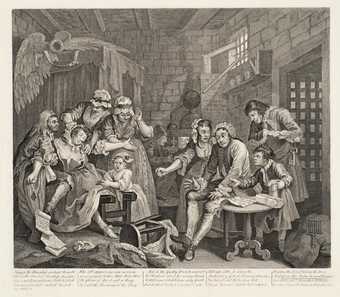

Fig.20

William Hogarth

‘Scene in a Madhouse’, from A Rake’s Progress (plate 8) 1735–63

Tate T01794

The eventual series bears a more oblique relationship than is usually acknowledged to both of its ostensible points of reference. Hockney explained how the Royal College of Art’s intervention had diluted his original intention, which was ‘to take Hogarth’s titles and somehow play with them and set it in New York in modern times’. But what actual titles did he have in mind, as there is in fact no definitive titling for the Hogarths? Was he thinking, for instance, of the prints, or the suite of paintings in the Soane Museum in London? In truth, Hockney’s eventual sixteen titles on the prints correspond quite minimally to Hogarth’s eight, despite his remark about his ‘sixteen retaining the numbering from one to eight and most of the titles in the original tale’. The implication is that the Hockneys come in pairs, 1a and 1b etc, which together match each one of the Hogarths. Thus, we might say that Hogarth’s ‘The Young Heir taking Possession’ (fig.18) resonates with the print showing Hockney arriving in New York, to take up his spiritual inheritance, but more directly with his selling prints in ‘Receiving the Inheritance’ (figs.5 and 6). Hogarth’s ‘Surrounded by Artists and Professors’ is presumably the equivalent to Hockney’s more solitary experience of visiting Washington, D.C. and viewing important cultural sites, such as the Jefferson and Lincoln monuments (titled ‘Meeting the Good People’), while the ‘good people’ theme is elaborated in attending the gospel concert, with its religious connotations (fig.7). Thereafter any such rigorous pairing and numbering systems seem to dissolve. Perhaps Hogarth’s brothel scene is the model for a much less dissolute visit to a bar, and for ‘Disintegration’, where he confronts an enormous glass of whisky, evoking a poster advertisement (fig.15). ‘The Arrest’ for debt in the Hogarth is reimagined by Hockney as an expulsion from affluent society, under the heading ‘The Wallet Begins to Empty’ (fig.14). ‘Marries an Old Maid’ is the scene recapitulated most directly. Hogarth’s ‘Scene in a Gaming House’ seems not to be echoed at all, while his ‘Prison Scene’ (fig.19) may be echoed in ‘Cast Aside’ (fig.16) but turns more literally into ‘Viewing a Prison Scene’ in a movie (fig.12). ‘Scene in a Madhouse’ (fig.20) becomes, in Hockney’s hands, the image of the young men listening to pop radio on their headphones, with ‘Bedlam’ as the writing on the wall, both literally and proverbially (fig.17). Ironically, Bedlam, the dreaded prison in Hogarth’s final print but subsequently a term evoking somewhere very noisy, takes the form of a strange, silent world, with everyone uniformly immersed in their private bedlam of the endless pop songs pumped out on commercial radio.

Critics have been lured into reading into the Hockney series an equivalent to Hogarth’s idea of a modern moral narrative, combining comic elements with an undeniably serious purpose. According to one typical commentary, Hogarth’s ‘themes are still found in Hockney’s work, but he titles them differently and they do not serve to illustrate a moral tale, that of a Rake’s downfall, but a social dilemma, the loss of individuality within a commercial society’.52 Critic Andrew Brighton ventured a more politicised interpretation. Whereas the Hogarths had projected ‘a tale of squandered inheritance’, Hockney recounts ‘the adventures of a young meritocrat discovering the American good life’. Rather than madness, ‘Bedlam for Hockney is to be among the mindless mass, the “other people”. Bedlam is the masses and mass culture – ears plugged into swinging WABC. The ticket needed to join “the good people” is a full wallet.’53 For art historian Jonathan Weinberg, in a similar vein, ‘the seduction of American consumer culture and its possible corrupting effects are at the centre of David Hockney’s A Rake’s Progress’.54

Such moralistic readings seem out of kilter with the playful feel and disconnected narrative structure of the series. Any trigger deriving from New York’s ‘Hogarthian’ underbelly is certainly not visible in the completed work. Indeed, an alternative reading of the underlying, programmatic ‘message’ of the series might be that the joys and sorrows of the contemporary world are a good deal less intensely felt, more standardised, banal and passive, than those confronted by Hogarth, a very contemporary artist in some ways but one whose mindset was rooted in traditions of Christian morality and tragic aesthetics that had come to seem dated. The Hockney figure inhabits the very different notion of being a rake, or rakish, that had come to prevail in more recent times, lacking the monstrous, immoral connotations of earlier conceptions, and understood more as a youthful ‘rebel without a cause’. Hockney was asserting, we might say, not only that modern life had moved on but also that the prevailing conditions of artistic practice in 1962 were very different from how such things stood in 1735. Rather than the viewer being instructed what to think and feel, now ‘you have to interpret it all’. Art, we infer, has shed its didactic purpose, and become a vehicle rather for the exercise of playfulness on the part of both artist and viewer. The inclusion of the sets of stairs and the serpent’s head in different scenes might even be taken to introduce reference to the well-known board game ‘Snakes and Ladders’, reinforcing the implication that the individual’s progression through life may have as much to do with the throw of the dice, or luck, as with character and moral choice. An interest in the diagrammatic imagery of board games is again paralleled in Boshier’s contemporary work.55

Hockney’s own departures from the original may have been encouraged by a familiarity with the several other modern adaptations of A Rake’s Progress. These had included a 1935 ballet, with sets by Rex Whistler; a 1945 film starring Rex Harrison, with the story loosely transposed to modern London; and most famously the 1951 Stravinsky opera, with libretto by W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman, which retained the eighteenth-century setting but significantly modified Hogarth’s narrative. Such works might at least have reinforced Hockney’s impulse to take the Hogarths as a springboard for spinning a personal variation. In his case, the relationship with the eighteenth-century model could be compared to that between My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean and its folk song source, which served as a pretext for depicting, with suitably parodic and wry detachment, what we take to be his revelation of his personal experiences and feelings. Indeed, the artistic references could be taken to insert a British cultural filter between artist and subsequently viewer and a set of experiences that must, in the early 1960s, have seemed exotic and quintessentially American, such as skyscraper architecture, concerts of gospel music, political rallies given over to registration rather than social policy, funeral display among the black community, transistor radios, big and bold adverts, jogging and gay bars. It is more compelling to view the Hogarths as giving Hockney licence to depict modern life, in a sequence of images, rather than stimulating him to project his own version of a didactic narrative.

The Hockneys are also remote from the elaborate artistic language of the eighteenth-century prototypes. Viewing Hockney’s A Rake’s Progress in purely aesthetic terms would surely not bring the example of Hogarth to mind. In the very first book-length treatment of pop art (1965), Mario Amaya already noted:

These etchings have little to do with Hogarth, despite their title, except that they come from the same English fondness for social satire. They are related more to the inventive freedom of style in the traditional English lampoon-caricature, which goes back to Gillray, Spy and others. Thus Hockney seems to have returned to a type of satire which Lawrence Alloway considered the first truly popular art.56

Other points of reference also seem relevant. One might see a general stylistic and technical debt to printmaking by Picasso, such as in the ‘Vollard Suite’ where line drawing is sometimes combined with aquatint. But Hockney’s faux naïve figure style, with variations of scale indicating relative narrative importance, and the use of simplified architectural features as settings for the figurative action, seem more closely to reflect his documented enthusiasm for early Renaissance art, especially the work of Duccio. Thus, we might discern an echo in Hockney’s first scene of the composition of Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem, as devised by Duccio for the Maestà altarpiece (1308–11). The schematic perspective of the table and inconsistent scale of the figures evoke scenes such as The Last Supper from the same source. Equally the discarded Hockney image There Will Never be Another Like It is strikingly reminiscent of Duccio’s depiction of the Angel sat on the tomb announcing the Resurrection to the Three Maries.57 Likewise, we might note a distant echo of the Expulsion from Paradise theme, as depicted by an artist like Fra Angelico, in Hockney’s depiction of the wallet beginning to empty, while the tree in ‘The Seven-Stone Weakling’ seems to have migrated from an early Renaissance picture.58 The story-telling dimension of such Old Master religious art was compatible, of course, with Hogarth’s secular morality tale, while the stylistic reference to the Italian ‘primitives’ reinforces the characterisation of the Hockney/rake figure as a wide-eyed innocent.

A Rake’s Progress has been seen to incorporate reference to the work of one of the first British artists to look back to Pre-Raphaelite artistic models, and also the single pre-twentieth-century British figure who spoke most compellingly to his successors of the modern period, namely William Blake.59 In the opening image, for instance, the reference to the Flying Tigers airline, the American carrier with which Hockney had flown across the Atlantic, takes on the Blakean resonance of ‘Flying Tyger’. The engagement here and elsewhere with Italian art of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries also emphasises continuities between Hockney and Stanley Spencer (1891–1959), an obsessive fan of Renaissance art whose work Hockney had admired since his Bradford days and would continue to revere.60 In relation to A Rake’s Progress, we might wonder whether Hockney was thinking at some level of Spencer’s account of his own quotidian experiences as a hospital orderly, and then at the front in Macedonia, in the rectangular scenes incorporated at the lower register of the great Burghclere Chapel decoration. The subsequent visit that Hockney and fellow artist Patrick Proctor paid to Spencer’s major masterpiece in Wiltshire, which had passed into the ownership of the National Trust, is documented by their signatures in the visitors’ book.61

The idea that Hockney’s art was shaped to some degree by a sense of British roots is reinforced by the general aesthetic affinities visible in the etchings with the work of Christopher Wood (1901–1930), which provided another model for a seemingly naïve mode of figuration, devoted to scenes of unspoilt existence in Cornwall and especially in Brittany. Renewed awareness of Wood’s work in the London art world was prompted by an important exhibition at the Redfern Gallery in early 1959, which also generated a substantial illustrated publication. Beyond his artistic appeal, Wood surely exemplified for Hockney how an artist might project ease with his homosexuality, as apparent in Wood’s portraits, male nudes and, above all perhaps, in his painting Nude Boy in a Bedroom 1930, a rear view depiction with implicit sexual resonances, that strikingly foreshadows Hockney’s own distillation of homosexual desire in a work such as Peter Getting out of Nick’s Pool 1966 (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool).62

Hockney’s personal experiences during those two to three months in America is the second terrain to which the etchings might be said to make only oblique and selective reference. A Rake’s Progress may give off the general impression of being a travelogue, but the artist himself disclaimed that the tale was autobiographical. ‘It is not really me. It’s just that I use myself as a model because I’m always around.’63 One occasional determinant was finding equivalents to the scenes chosen by Hogarth to describe the rise and fall of Tom Rakewell. But we might note, too, the absence of all manner of experiences that doubtless came his way, such as visiting tourist and architectural sights like the Empire State Building, which he mentioned as on his list to Kitaj, or travelling on the subway.64 Snapshots capture Hockney’s visit to Coney Island with his artist friend Billy Apple.65 His most recent biographer records that Hockney took part in an anti-nuclear march in Greenwich Village.66 Less surprisingly perhaps, the activity of looking at art does not feature in A Rake’s Progress. There is the reference to meeting William Liebermann and selling the prints. But we can assume that Hockney spent a good deal of his time going round the galleries of New York that summer, possibly accompanied by Berger and Amacker. In July Hockney reported to his family that ‘the museums here (and there are plenty of them) are quite marvellous and will take some time to absorb’.67 Hockney has stated that Claes Oldenburg was the only American contemporary artist he actually met on his trip, when the future pop artist happened to be installing his ground-breaking ‘papier mâché shirts and ties’ at the Green Gallery.68 The group show in question opened in September so the encounter occurred towards the end of Hockney’s stay.69 Otherwise, we know next to nothing, from the etchings or any other source, about Hockney’s engagement with the New York art world.

Such a prolonged stay doubtless yielded a plethora of experiences and artistic ideas. Future research may establish the additional motifs Hockney had contemplated for A Rake’s Progress before he decided to edit the series down to the sixteen images. But, in its final manifestation, the series focuses upon a miscellaneous selection of the entertainments and amusements on offer in the city, strung together into a loose storyline. Overall A Rake’s Progress comes across as an amusing fiction, one might almost say fairy story, about the adventures of a young Englishman in New York who ends up going native. The Hockney figure who is Tom Rakewell’s successor has fun, gets around, spends a bit too much on shopping, drinks a bit too much, and succumbs to the lure of mass culture when he gets low on funds. But nothing too terrible or traumatic happens. As a droll tale of a young man having to shed his fantasies and come to terms with more mundane realities, A Rake’s Progress brings to mind not so much the historical Hogarth as the contemporary Billy Liar, the highly successful novel from 1959 by Hockney’s fellow Yorkshireman Keith Waterhouse.70

In sum, neither the Hogarthian rake nor the autobiographical narratives take one very far in pinning down the genesis and aesthetic character of A Rake’s Progress. It may be, rather, that both served as armatures for artistic invention, enabling Hockney to channel his engagement with the contemporary cultural scene. The assimilation of American popular imagery was, of course, an emerging and provocative artistic strategy in New York at the time of his visit. In that context, it is likely that Hockney took back with him to London not just personal memories and drawings, but also a cache of magazines, catalogues and images that could then function as visual aids when devising episodes for inclusion in A Rake’s Progress. ‘Disintegration’ is a fairly literal adaptation to a 1960 advert for Bellows Whisky. ‘The Start of the Spending Spree’ likewise refers to adverts for Clairol, a brand heavily and successfully promoted at this time to women, which Hockney (like his American friends and also Billy Apple) had started using. Again, subsequent investigations may establish specific sources in popular visual culture for elements in other scenes.

One undoubted derivation indicates the breadth of Hockney’s visual resources. The image Death in Harlem (fig.13) seems the least explicable as an autobiographical episode during his trip, beyond implying he had paid a visit to Harlem. The artist subsequently connected his idea to a photograph by Cecil Beaton, an early collector of his work.71 But, on visual grounds, one could more readily envisage a point of departure in one of the many such photographs produced by James van der Zee for Harlem funeral parlours. Van der Zee had been a significant figure in the Harlem Renaissance during the interwar period, and admiration in the New York art world culminated in the publication of The Harlem Book of the Dead (1978). Indeed, it transpires that Hockney’s particular source for his print was actually encountered in Beaton’s 1938 illustrated book about New York, accompanied by the same caption ‘Death in Harlem’, although Van der Zee is not identified by name as the creator of the image (fig.21).72 Since many of the illustrations are indeed Beaton’s own photographs, Hockney’s conflation is hardly surprising. More generally, he was fascinated no doubt by Beaton’s account of Harlem as ‘a negro reservation in a white man’s city’, with its own vibrant homosexual and ‘drag’ culture.73

Fig.21

Cecil Beaton, Cecil Beaton’s New York, London 1938, p.178.

On another level, we might suppose that the culture of experimental printmaking that Hockney encountered at Pratt encouraged the general notion of a series or portfolio, as both an aesthetic and marketable proposition. The models offered by figures like Dine and Newman were noted earlier. The comparison between My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean and ‘Melancholy Breakfast’ established the possibility that Hockney was also aware of the Stones portfolio. Hockney’s etchings for A Rake’s Progress are more purely visual, and employ quite different techniques, but it is worth considering the possibility that, at some level, the informal designs and fragmented imagery in the Rivers/O’Hara collaboration may have been a catalyst for Hockney’s own conception of a multi-print cycle. If Hockney’s work is viewed as less homage to than parody of Hogarth’s rake narrative, then we might see loose parallels with the literary work of his British contemporaries such as Bradbury, for whom parody was a persistent strategy, and indeed with the wider burgeoning of satire associated with the comedy stage revue Beyond the Fringe, Peter Cook’s Establishment club, and the launch in 1961 of the satirical and current affairs news magazine Private Eye. Wit and irreverence were in the air in the early 1960s. But, in a different way, this was also a feature of avant-garde culture in New York. We might align Hockney with Rivers’s tongue-in-cheek appropriation of a revered historical model in his painting Washington Crossing the Delaware 1953 (followed by a more abstracted 1960 variant), or with the work of a poet, Frank O’Hara, whose major creations, according to poetry scholar Marjorie Perloff, ‘follow Romantic models, but he almost always injects a note of parody, turning the conventions he uses inside out’.74

The autobiographical mode of A Rake’s Progress was likewise in tune with a current sensibility in America. In advising Hockney to make art that related to his own life and personal commitments, Kitaj was in effect relaying the aesthetic programme that O’Hara had developed for his poetry in the late 1950s. The short text by the poet in The New American Poetry offered an account of his poetic that would surely have resonated with Hockney, if he indeed encountered it: ‘I am mainly preoccupied with the world as I experience it … What is happening to me, allowing for lies and exaggerations which I try to avoid, goes into my poems … It may be that poetry makes life’s nebulous events tangible to me and restores their detail; or conversely, that poetry brings forth the intangible quality of incidents which are all too concrete and circumstantial.’75 The sentiments match the informal, highly concrete tenor of O’Hara’s poetry, exploring the transient play of sensations, emotions and fantasies provoked by life in the city. This culminated in the conversational tone of the so-called ‘lunch hour poems’, composed during his breaks while working at the Museum of Modern Art. If we were seeking more specific links to O’Hara in A Rake’s Progress, we might note how the fifth plate, with the Clairol allusion, recalls the 1959 poem ‘Rhapsody’, in which the poet makes a characteristic transition from the mundane, and the New York street indelibly associated with the advertising industry, to wondrous revelation:

515 Madison Avenue

door to Heaven? Portal

stopped realities and eternal licentiousness.76

Could it even be that, in developing the Death in Harlem image from the photograph in Beaton’s book about New York and so injecting a note of pathos into the series, Hockney was taking bearings from of one of the most wonderful of O’Hara’s ‘I do this, I do that’ poems, as his approach has been caricatured? ‘The Day Lady Died’ was another of the poems included in the 1960 New American Poetry anthology. Like A Rake’s Progress it is replete with numbers and capitalisations, as well as humdrum everyday experiences, until it reaches its poignant conclusion prompted by seeing a newspaper reporting the death of the jazz singer Billie Holliday:

and for Mike I just stroll into the PARK LANE

Liquor Store and ask for a bottle of Strega and

then I go back where I came from to 6th Avenue

and the tobacconist in the Ziegfeld Theatre and

casually ask for a carton of Gauloises and a cartoon

of Picayunes, and a NEW YORK POST with her face on itand I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of

leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT

while she whispered a song along the keyboard

to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing77

Even if positing that link goes too far, we can sense a pronounced affinity between Hockney and a poet whose work was self-evidently autobiographical, but whose ambitions, according to Perloff, were remote from Romantic confessionalism: ‘the poet does not use the poem as a vehicle to lay bare his soul, to reveal his secret anxieties or provide autobiographical information’.78 For James Breslin, likewise, ‘rather than struggling to recover a lost core of identity, O’Hara creates a theatricalized self that is never completely disclosed in any of its “scenes”’.79 Those accounts sound congruent with the outlook elaborated in Hockney’s A Rake’s Progress. The idea of making a work about fragments of everyday experience, conveyed in a light and, so to speak, conversational tone, brings to mind O’Hara’s aesthetic. Hockney, too, cultivated a superficially autobiographical mode, but with everyday activities and imagery serving to keep at a distance any deeper psychic preoccupations or any notion of a core underlying self. Like O’Hara’s work, his series of images projects the sensibility of a latter-day flâneur, a notion that has become pervasive to the point of cliché in accounts of homosexual cultural life during the post-war decades.

The attempt here to complicate our understanding of Hockney’s A Rake’s Progress has yielded several paradoxes. On the face of it, the work projects an Englishman’s vision of New York, filtered through an English artistic paradigm. Yet it also seems illuminating to view A Rake’s Progress as presenting, in Hockney’s own artistic terms, a parallel to, perhaps emulation of, the inconsequential, playful, parodic manner elaborated in the work of stalwarts of the New York gay scene such as Rivers and O’Hara. An aspiration to produce work in this contemporary idiom may have been a primary catalyst, which subsequently became overlain with multiple decisions about what episodes to depict, within narrative frameworks implying both an autobiographical sequence and the fictive rise and fall of Hogarth’s unfortunate rake, and about the artistic language that would impose aesthetic coherence on the project. By that reckoning, it was contemporary American culture that in some sense prompted Hockney to conceive a work which also came to encapsulate a self-consciously British sensibility, in its Hogarthian resonance, affinities within earlier British modernism, generally ‘literary’ character, and air of ironic detachment. Equally, American models in art and literature may have encouraged him to develop a graphic project that was muted in its iconographic allusions to the artist’s sexuality, compared with the frank and polemical paintings he had been producing in the relative seclusion of his personal space at the Royal College of Art, but that nevertheless articulated a homosexual aesthetic through its artistic and literary citations and through its generally ‘camp’ tone, a term previously current in gay subculture but famously launched into high-brow critical discourse by New York critic Susan Sontag in 1964.80

I may have overstated the concrete connections and possibilities of ‘influence’, but the American aesthetic affinities of A Rake’s Progress are unmistakable. By way of one final incongruity, we might note that the print series narrates the declining fortunes of the fictive Hockneyesque figure, but as an artefact in its own right it celebrates the creation of a singular artistic identity, based on his assimilation of an array of available stimuli, high and low, British and American, contemporary and traditional, visual and literary, cultural and social. While the depicted rake, Hockney’s surrogate self, lapsed in the end into cultural conformism and anonymity, the actual Hockney succeeded with such works in realising his individuality and giving expression to a distinctive voice on the newly transatlantic art scene of the 1960s.