In recent decades calls for a more ‘global’ history of art have become increasingly insistent. The history of mural painting during the 1930s is an instance in which dialogue was truly transnational, standing in contrast to the nationalist emphases so often characterising studies of the period. In 1932, at the height of the Great Depression in Britain, leading art publication the Studio adopted a xenophobic and openly hostile attitude towards international art, conjecturing that what was needed now were ‘uncompromisingly British artists’.1 The publication’s about-turn, which was accompanied by vehement anti-modernism, marked a retreat from its internationalist perspective during the 1920s. As the collapse of the pound limited opportunities for artists to travel abroad and stemmed imports of foreign art, a 1932 Studio editorial warned: ‘Painters would be better advised to stay at home … and study life for a change … Britain is looking for British pictures of British people, of British landscapes … a thorough going nationalism.’2 Similar injunctions advocating a return to the aesthetics of indigenous naturalism were issued in other nations as well, with the widespread championing of regionalism and American Scene Painting in the United States offering a comparable case in point. However, the revival of interest in muralism was international in scope and belies any assumptions about the reactionary cultural isolationism of the period. Indeed, the 1930s were to become one of the most internationalist decades in British art. Such internationalism, accompanied by values of collectivity, collaboration and cooperation, is one of the very real achievements of the culture of the period.

Artists and cultural ideologues championed muralism during the 1930s as means of bringing art to a broad public audience. They were also seeking an alternative to the declining trade in easel paintings and the caprices of an elitist market system. For English artists, continental developments in wall painting, particularly those in France and Italy, frequently informed the terms of practice and debate, but so too did activities occurring farther afield, especially for artists on the left whose political ambitions were underpinned by a shared international vision for the future.3 Within the leftist artistic milieu, Soviet calls for the development of a ‘social art’ and the widely acknowledged influence of the Mexican mural renaissance meant that wall painting was embraced on both sides of the Atlantic, with the establishment of the Popular Front Against War and Fascism at mid-decade providing a powerful transnational alliance for the promotion of leftist culture.4 As this article demonstrates, it is thus next to impossible to understand English artists’ support for muralism during this period outside the context of international developments, notably those in America.

Politics, muralism and the Artists’ International

The significance of muralism in the United States has received considerable attention in art historical treatments of the period.5 The modernisation and revitalisation of American wall painting was the result of a number of cultural factors, perhaps most importantly the establishment from 1933 of federal funding for public art under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal administration.6 Scant mention can be found of the influence of the American example for artists in England, yet renewed interest in muralism was not limited to artists in the US or simply a response to conditions abroad. Notwithstanding obvious social, political and economic differences between an Old World empire in decline and a New World nation soon to be confirmed as global hegemon, the international impact of the Depression meant that a comparable situation of crisis existed in both countries, with artists facing similar challenges. These included a failing art market and the dwindling of private patronage; a questioning of the sustainability of capitalist democracy in decay; the grim and inhumane realities of poverty and mass unemployment; the rise of fascism; and the ominous spectre of another world war. Artists in England, as in America, were acutely aware of the need to establish the capacity of art to contribute to social change and to identify their role in the face of mounting uncertainty and turmoil.7

A revival of large-scale painting was already under way in Britain during the 1930s, with newly commissioned murals adorning a range of public and private walls.8 A survey mounted at the Tate Gallery in London in May–June 1939 – Mural Painting in Great Britain, 1919–1939: An Exhibition of Photographs – confirmed the promising state of recent developments. Despite acknowledged difficulties in showing murals within a museum setting, Tate displayed black and white photographs and portable panels as a substitute for monumental works that remained in situ, and remained undeterred in its ambition to inspire artists and patrons alike. Furthermore, the accompanying catalogue resonated with cultural optimism only months before Britain declared war on Germany. Praising the formation of the British Society of Mural Painters earlier that year, the show encouraged community support for the new mural movement and looked forward to ‘the great possibilities that lie ahead’.9 Among the highlights singled out for emulation, the catalogue noted that public patronage resulted in murals for St Stephen’s Hall, Westminster (1927), by artists such as Vivian Forbes, Colin Gill, A.K. Lawrence, George Clausen, Thomas Monnington, Glyn Philpott, William Rothenstein and Charles Sims, while the private sponsorship of Lord Duveen was responsible for a mural executed by Rex Whistler for the Tate Gallery restaurant (1926–7) and the decorative panels by Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious for the walls of the refectory of London’s Morley College (1930). As the catalogue concluded, ‘There are already signs that the modern movement in mural painting is becoming conscious of its potentialities.’10

It was also during the 1930s that muralism’s potential to serve an explicitly political agenda was linked to its already celebrated decorative function and capacity for moral uplift. Given the mural’s monumentality, its public mode of address and its suitability for didactic purposes, the art form was championed by the Artists’ International group (AI), the most persistent and vocal proponent in the United Kingdom for democratising culture.11 The AI was a characteristic ‘front’ group of the period. Established in London in 1933 to promote united action, founding members included a number of Communist Party members alongside fellow travellers committed to pursuing an identifiably Marxist programme, with the group’s name invoking the Communist International.

Among the founders of AI were British artists Clifford Rowe and Pearl Binder, both of whom spent time in the Soviet Union during the early 1930s; they returned to London convinced of the need to organise internationally in joint support of the rights of artists and the working class movement. Their first exhibition, The Social Scene: The Social Conditions and Struggles of Today, mounted in a vacant shop at 64 Charlotte Street in the autumn of 1934, was accompanied by a manifesto, subsequently published in the December 1934 issue of the Studio, in which members echoed the left’s familiar rallying cry to use art as a ‘weapon’ in the class struggle.12 The group engaged in a diversity of activities, including propaganda work for Left Review, the journal of leftist intelligentsia founded in 1934 by the Writers’ International; the production and sale of inexpensive Everyman Prints, conceived to bring the work of established artists to a wide audience; and the circulation of exhibitions, with Pablo Picasso and Fernand Léger among the international sympathisers contributing work to their shows. Members also published a journal sporadically and in different formats from 1934, beginning with the Artists’ International Bulletin (1934–5) and continuing with the Artists’ International Association Bulletin (1935–6 and 1939–47) and the Artists’ News-Sheet (1936–8).

Under the chairmanship of architect and designer Misha Black, who was the driving force behind the AI throughout the 1930s, the group pursued their aims in a cultural climate defined by hunger marches, a hugely oppressed working class and mass demonstrations against the degradation of the means test, which was designed to measure whether a worker qualified for employment support. Although the General Strike of 1926 was still a recent memory, the Labour Party was destroyed as an effective independent force in Parliament when it fell from office in September 1931. A politically and economically demoralised nation was ruled by a National Coalition Government for the remainder of the decade. In an era characterised in a popular slogan as one of ‘Poverty in the midst of Plenty’, and prior to the revelations of the ruthlessness of Stalinism, the Soviet Union seemed to many a promising alternative to the inequalities of a moribund capitalist society. The emergence of the British Union of Fascists in 1932, followed by Hitler’s chilling victory in Germany in 1933, brought a heightened urgency to the need for radical action.

With the advent of the Popular Front and directives from the Communist International (known as the Comintern) for communists to broaden their base through unity with social democrats and other anti-fascist groups, the AI adopted a class-collaborationist line and reconstituted itself in 1935 as the Artists’ International Association (AIA), now pursuing a more inclusive membership to mobilise against fascism. Bringing together artists from across the stylistic spectrum, the group dedicated itself to safeguarding a democratic culture and accorded particular prominence to muralism as a component of this project. To the ‘potentialities’ of muralism noted in the 1939 Tate Gallery exhibition catalogue, the AIA introduced a new element, namely the emphasis on the mural as an essentially popular art form, with its democratic attributes deriving from its content and location. Whether in the form of wall paintings, billboards or large-scale banners, the mural was championed as a means of creating a socially engaged art for a mass audience, a perspective influenced by the example of New Deal patronage for public art in the US and the Mexican mural movement.

Fig.1

Installation view of panels from Thomas Hart Benton’s The Arts of Life in America 1932

New Britain Museum of American Art, New Britain

Artists in the United Kingdom did not enjoy an equivalent to federal patronage until the outbreak of war, but they took important cues from their American counterparts.13 The July 1933 issue of the Studio, which had a long-standing tie-up with the American magazine Creative Art, showcased muralism in the United States with a well-illustrated article on a cycle of paintings executed by regionalist artist Thomas Hart Benton for the Reading Room at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.14 While Benton’s tempera panels comprising The Arts of Life in America 1932 (fig.1) were lambasted by many New York critics, including the editor of Creative Art, Henry McBride, who denounced them as ‘pure tabloid’ for their inclusion of racist caricatures and vulgar satire, the Studio found less to fault.15 Benton’s turbulent imagery, with its jarring sense of rhythm and action, demonstrated that ‘mural art should not simply be the decorative hand-maiden of architecture’. In keeping with the Studio’s own conservative outlook at this juncture and its support for home-grown artistic expression, the murals’ evocation of the ‘crude realities of twentieth-century lower middle class life’ was an endorsement for painting everyday life. An artist no longer required a studio in Paris when ‘pictorial themes can be found among the dance-halls, boxing-rings, movie-sets and agricultural machinery that make up America’.16 Furthermore, the Studio found in Benton’s focus on ‘authentic’ yet contradictory aspects of American life the confirmation that an artist in a democracy must make ‘no compromise with his conviction that [he] must express his experiences’.17

Carline, Evergood and ‘socially conscious’ art

The most extensive coverage of the American cultural milieu came from the British artist, writer and AIA member Richard Carline, who shared first-hand knowledge of the mural renaissance, artists’ organisations and the New Deal cultural programmes. Carline was a painter, administrator and writer with strong convictions about the social duty of artists. He served on the Western Front and in the Middle East during the First World War, settling in London’s Hampstead after his military service. His Downshire Hill home became a meeting place for artists such as Henry Lamb, John Nash and Stanley Spencer who avidly discussed recent developments in art, including futurism, the significance of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) and the critic Clive Bell’s much-discussed concept of ‘significant form’. From the early 1930s Carline’s own painting practice was eclipsed by his active role in local, national and international artists’ organisations. In the years preceding the Second World War he was among the founding members of the Artists’ Refugee Committee set up in Hampstead to aid artists fleeing fascism. He supported the international mandate of the AIA from the outset and sought to cultivate connections with artists in other countries. While these links remained largely unformalised, a long-standing friendship between Carline and American social realist painter Philip Evergood offered direct access to American developments.

Evergood gained impeccable credentials as a politically engaged muralist during the 1930s and became a favourite of the American left.18 Although he was born in New York, his Cornish-Irish mother insisted her son receive a ‘proper’ British education. He attended boarding schools in England and graduated from Eton in 1919. He subsequently left Cambridge University to study from 1921 to 1923 under Henry Tonks at the Slade School of Fine Art, London. It was at the Slade that he befriended Carline and joined the Downshire Hill Circle. As Evergood recalls, it was within this group that he first encountered artists whose primary interest lay with contemporary life rather than the old masters. For the remainder of the 1920s Evergood divided his time between America and Europe, including periods in Paris – where he studied with cubist André Lhote and English émigré painter and printmaker Stanley Hayter – and visits to Italy and Spain. He returned to America for good in 1931 and studied with Ashcan School artist George Luks at the Art Students League in New York.

Fig.2

Philip Evergood, The Angel of Peace Offering the Fruit of Knowledge to the World, or Artist’s Fantasy 1932–58

Oil on canvas

2134 x 1219 mm

Evergood’s return to New York coincided with Diego Rivera’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). He was deeply inspired by the example of the Mexican muralists and found in Rivera’s murals a much-needed ‘ray of hope’ for a socially engaged yet formally sophisticated art.19 Evergood was particularly keen to paint a mural and a few months later he secured an invitation to execute a monumental panel for MoMA’s 1932 exhibition Murals by American Painters and Photographers. The show was conceived prior to the inauguration of federal patronage for public art and took advantage of burgeoning interest in the Mexican mural renaissance to promote American muralism. Evergood’s panel, The Angel of Peace Offering the Fruit of Knowledge to the World, now known as Artist’s Fantasy (fig.2), presents a prescriptive vision of human development throughout history.20 The composition reflects an effective adaption of narrative techniques he encountered in Trecento and Quattrocento frescoes, but put to new purposes. While still reliant on allegory, his mural tackles politically topical subject matter and demonstrates a nascent interest in realism. The Angel of Peace emerges from the Tree of Knowledge and offers her fruit to representatives of the arts, including a painter, a sculptor, a dancer and a musician, who gather in a lush meadow below. The mural’s focus on the peaceful arts encourages a redirection of humanity’s energies towards the nurturing of life and the creation of beauty, and away from the temptations of war, hatred and greed. Evergood’s high-keyed, often discordant colour, combined with his expressionist distortion of form, already distinguished his approach to realism from exponents of proletarian art. His work is unmistakably underpinned by a progressive social consciousness, yet does not adhere to the naturalism conventionally associated with ‘social’ art. He saw himself as a modern artist and did not advocate ‘leaflet painting’; his aim was ‘to paint a good picture – a work of art’.21

Fig.3

Philip Evergood

Music 1933–59

Oil on canvas

1702 x 3035 mm

Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia

The MoMA exhibition introduced Evergood to the murals of fellow social realists Ben Shahn and Hugo Gellert, who were similarly affected by the Depression. Like these artists, Evergood opposed prevailing social, political and economic conditions in America and increasingly gravitated towards the organised left during this period. Although he never joined the Communist Party, Evergood was a long-term Party loyalist and subsequently found ways of pursuing a socially engaged muralism. In 1933 he began attending meetings at the communist John Reed Club and was a member of the parallel Pierre Degeyter Club, a left-wing branch of the Workers’ Music League named in honour of the composer of the ‘The Internationale’ (the song of the Paris Commune of 1871 that was to become the anthem of the International Workingmen’s Association). Evergood painted a second mural entitled Music 1933–59 (fig.3) for the Degeyter Club’s meeting rooms. The large canvas features an inter-racial group of men and women working in ‘harmony’ to make music together.22 That same year, 1933, he signed onto the relief rolls of the Public Works of Art Project, later joining the New York Mural Division of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (WPA/FAP) in 1936. As part of the latter project Evergood painted a mural for the Richmond Hill branch of the Queensborough Public Library. Completed in 1937, The Story of Richmond Hill presents the history of the garden city as the result of enlightened government planning under the New Deal.

Evergood celebrated the Roosevelt administration again in his next mural, The Artist in the New Deal 1938. Painted for a group exhibition at the American Contemporary Artists’ Gallery in New York to support a Federal Arts Bill seeking to ensure permanent government patronage, the panel’s complex iconography shows the apotheosis of the artist from suffering and isolation to integration within a thriving social democracy.23 Evergood was forced off the rolls of the FAP in 1937 due to a temporary increase in his wife’s income, although having now established himself as a serious and capable artist he was re-hired a year later as supervising manager of the New York Easel Division. Evergood’s skill and reputation contributed to the securing of a further federal mural commission under the Treasury Department’s Section of Fine Arts, whose mandate was not work relief but the selection by competition of the ‘highest quality’ fine art to decorate federal buildings (a mandate whose genteel and inegalitarian presumptions came under consistent and fierce attack from the left). Dispatched to the South, Evergood’s inter-racial scene of productive labour Cotton – From Field to Mill 1938 for the US Federal Post Office in Jackson, Georgia, proved considerably more controversial than his mural for the Degeyter Club.

Throughout the 1930s Evergood maintained links to the artistic community in Britain, particularly through his continuing friendship with Carline, who followed his activities with interest. Evergood was a founding member of the Artists’ Union in New York, the de facto bargaining agent of workers on the Federal Arts Project, and was elected to the executive board of the Union in 1936, serving as its president a year later.24 As the Union was well aware, the WPA was conceived by Roosevelt from the outset as a temporary measure, to be disbanded as quickly as the economy would permit, and the Union’s fundamental goal was to establish its permanence in one form or another. Ideologues of both the Treasury Section and Federal Art Projects envisioned a permanent shift away from the market system and the Union thus worked tirelessly to resist the government’s efforts to curtail work relief. Evergood was frequently involved in demonstrations to stop funding cuts to the arts projects, and he joined workers’ marches in Washington, D.C., to protest WPA layoffs. He actively supported the establishment of the American Artists’ Congress in the summer of 1935 and assumed a leading role in a range of Popular Front initiatives, including the organisation of the first American art exhibition mounted in 1936 in support of the Loyalist cause during the Spanish Civil War.

Carline undertook extended visits to America during this period. Taking his first trip there in 1928, he returned in 1934, travelling to New York City where he was introduced to the Artists’ Union and later the American Artists’ Congress. Through Evergood he met fellow leftist artists Harry Gottlieb and Stuart Davis, both active in WPA arts projects and the collective organisations of the decade. Carline carried a letter from Misha Black, chairman of the AIA, to Davis, a widely respected artist-activist who served as first President of the Union and National Secretary of the Congress, in which Black expressed a commitment to Anglo-American cooperation.25 Once back in London Carline joined the AIA as a direct result of the example set by American artists and was keen to establish international links between sister organisations. He crossed the Atlantic again in 1937, this time to learn more about public art and familiarise himself with how the WPA art programmes operated. He was especially eager to learn more about muralism and was aware that the chief stimulus behind the FAP derived from Mexico. After a visit to Dartmouth College in New Hampshire to see José Clemente Orozco’s recently painted frescoes The Epic of American Civilization 1932–4, he travelled to Mexico to view the murals of Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros first hand. Carline was intent upon bringing the American example to England:

I was very excited by the WPA and New Deal artists … It had made the artists there feel they were a part of society and wish to do something related to their place in society and social life. It was linked to the Mexican Movement; they had done very much the same thing there.26

Carline was impressed with the ‘tremendous political change’ under Roosevelt, specifically the scale of New Deal relief measures for which no precedent existed. He was also struck by artists’ solidarity and activism. As he relayed to the AIA in the September 1938 issue of their Artists’ News-Sheet, American artists formed collective organisations that professionalised their activities and gave them a ‘militant impulse’.27

Making his point, Carline recounted Evergood’s experience of the artists’ sit-down strike to protest funding cutbacks and layoffs at the New York WPA offices in December 1936; 219 artists were arrested and Evergood ended up in jail, badly bruised and bleeding from a police beating. A year later, under Evergood’s presidency of the Union, talks were initiated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), resulting in formal affiliation in January 1938 as the United American Artists, Local 60, of the United Office and Professional Workers. The recently established CIO was becoming a significant power in the nation and it was hoped that affiliation would increase the Union’s bargaining power and political leverage. As Carline continued, unionised artists in America were ‘a conscious section of the workers’ and aligned their interests with those of other labourers.28 It was thus ‘not surprising’ to find a ‘new school of “socially-conscious” painting’ emerging in the United States.29

Adopting a view cognate with that being enunciated in America by independent leftist art critic and historian Meyer Schapiro, Carline championed a ‘social’ art that demonstrated solidarity with the interests of workers, one with ‘a consciousness of the reality of the social-economic situation and a readiness to combine and even fight for common ends’.30 While Carline supported a realist aesthetic, he was in no way an apologist for the Communist Party’s official aesthetic. His stance on artistic style, like Schapiro’s, was at odds with that of more doctrinaire commentators such as Francis Klingender, thereby complicating customary associations between a leftist political perspective and unqualified support for a naturalist and often banal social realism.

Fig.4

Philip Evergood

Mine Disaster 1933–7

Oil on canvas

1016 x 1778 mm

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia

Meanwhile Evergood offered a model consonant with the priorities of both Carline and Schapiro. His paintings presented the concerns of labour in an advanced stylistic vocabulary synthesising the techniques of modernism with those of historical Western painting. For example, his large triptych Mine Disaster 1933–7 (fig.4) depicts a contemporary political theme in a sophisticated realist idiom characterised by mannerist linear distortions combined with the vibrant colour juxtapositions associated with German expressionism. The striking triptych was Evergood’s contribution to the Hunger Fascism War exhibition at the New York John Reed Club during the winter of 1933–4. Punctuated by intense passages of chiaroscuro, the subterranean darkness of the coalmine is illuminated by flashes of light from the head-torches of the miners, lending the soot-blackened workers a haloed effect. The disjunctive composition indexes Evergood’s familiarity with early Italian fresco painting and avant-garde techniques of cinematic montage. The large size of the canvas suggests it may have been conceived as a mural. The left side of the triptych, Labor in Darkness, pictures coal mining operations and the right side, Tragedy of Entombment, depicts the disaster invoked by the painting’s title: a young miner trapped alive and partially buried by a cave-in. The centrepiece of the composition, Rescue Squad, shows a group of miners who have banded together to save their fellow worker; however, their grim, caricatured faces (reminiscent of painter George Grosz’s deformed physiognomies) suggest that their heroic attempts were unsuccessful. The coffin laid at the feet of the miner’s family in the lower right-hand corner confirms the deadly outcome.

With its focus on the life-threatening conditions that miners were forced to endure on a daily basis, Evergood’s Mine Disaster is surely a response to the strike wave that swept through the coalfields after Roosevelt secured the National Industrial Recovery Act in June 1933, a law passed by Congress enabling the president to regulate industry and establish codes of fair practice, including collective bargaining rights. Under the powerful leadership of John L. Lewis, representatives from the United Mine Workers (UMW) spread across America to organise coal miners into unions; paramount among their demands were improvements to mine safety. Although Lewis was a Republican and violently anti-communist, the left played a conspicuous role in the resurgence of the UMW during the decade, with Lewis making use of communist organisers following the establishment of the CIO in 1935. From mid-decade, the UMW not only gained members and influence, but made substantial contributions to the widespread revitalisation of the labour movement in the US.31 Evergood’s Mine Disaster was almost certainly conceived in support of the UMW’s cause; while assuredly tendentious in the narrative it depicted, the painting did not adhere to conventional dictates associated with social realism during the 1930s. Mine Disaster fuses modernist techniques with legible and politically charged content to create genuinely relevant art where, as Schapiro approvingly observed in the Artists’ Union journal Art Front, the workers ‘find their own experiences presented, intimately, truthfully, and powerfully’.32

Evergood had no obvious counterpart in London and English protagonists of a similar style of realism were bereft of local precedent. As Carline later explained, ‘When I came back to England in 1938, we thought it would be extremely valuable to see some of this kind of art in London. The activities of ordinary people, factories, industries – socially conscious art. I thought this would be an eye-opener for British artists and absolutely in line with what the AIA wished to do themselves.’33 Following his encounters with the paintings of Evergood and other American realists he admired, such as Robert Gwathmey, Anton Refregier and Ben Shahn (all of whom painted murals under the New Deal), Carline recognised that one of the key problems facing the AIA was identifying a suitable aesthetic to support. This is not to say that there was critical consensus amongst leftists in America on aesthetic matters, not even within the remit of realism, but there were some accomplished artists whose works fulfilled Carline’s formal criteria for an engaged social art.

A leftist aesthetic

The lack of direction within the AIA was evident from the outset when in 1934 it mounted The Social Scene – the first of a series of large group exhibitions dedicated to socio-political themes. Following the thematic lead of the similarly titled exhibition The Social Viewpoint in Art, held two years earlier at the John Reed Club, The Social Scene demonstrated that while English leftists sought to create a united front for artists and express their solidarity with the working class movement, there was seemingly no contemporary visual tradition from which to advance. Despite the Communist Party’s imposition of social realism until the mid-1930s, there was at first very little in England by way of an authoritative and accessible theoretical guide to assist artists in their ambitions to achieve a socialist art practice. Even prior to the establishment of the Popular Front, the AIA’s exhibitions provided a remarkably liberal and permissive occasion for artworks covering the whole gamut of contemporary practice, from non-objectivity to the most conventional naturalism.

This lack of sustained thinking on aesthetic matters was rectified to some degree in 1935 by the publication of a collection of essays entitled 5 on Revolutionary Art. Edited by sculptor and AIA Secretary Betty Rea, the volume brought together papers delivered at an AIA symposium. However, the range of views offered by authors Herbert Read, Francis Klingender, Eric Gill, A.L. Lloyd and Alick West were rife with contradictions, pointing to heated international debates within the Popular Front principally centred on La Querelle du Réalisme, the series of discussions unfolding at the Maison de la Culture in Paris. For Read, who was perhaps the most informed and sympathetic supporter of modernism in England, realism was not technically advanced enough to be revolutionary. Dismissing the widely celebrated work of Rivera as ‘feeble’ and ‘essentially second-rate’, he emphasised instead the transformative potential of abstraction and surrealism.34 Read was the chief spokesperson for Unit One, a group of modernist painters, sculptors and architects who denounced social realism as retardataire propaganda, including Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore.35 He was also an ally of surrealism, sitting on the organising committee and writing the catalogue for the inflammatory International Surrealist Exhibition held in London at the New Burlington Galleries in the summer of 1936.

Read’s stance was in direct contrast to that of Klingender, who viewed modernist developments as mere formalism and an extension of the nineteenth-century creed of art for art’s sake. Klingender was an orthodox Marxist originally trained in economics and sociology at the London School of Economics.36 He developed close ties with Jewish Hungarian Marxist art historian Frederick Antal, who was exiled in London from 1933. Antal lectured at the Courtauld Institute of Art and became the leading theorist of a social history of art in Britain. It was through Antal that Klingender cultivated an interest in the capacity of art to elicit social change, which led him to participate in the founding of the AIA and serve on its executive committee. Klingender mounted a materialist critique of the idealist tradition in art, developed during the 1920s in England by the formalist aesthetics of Clive Bell and Roger Fry. His assumption that art was a valuable form of ‘social consciousness’ has its origins in the cruder mechanical materialist thinking of Second International Marxist Georgi Plekhanov and is also indebted to the teachings of Antal. Klingender’s essay ‘Content and Form in Art’ for 5 on Revolutionary Art insisted that art could act as a ‘revolutionary agent’ and should be used as a ‘weapon’ to educate and agitate the masses in the class struggle.37 Although an association between realist art and political progress is essential to Klingender’s thinking, he espoused a surprisingly wide conception of realism. He was, however, adamant in his rejection of abstraction: ‘The purification of form as a means of expression had reached the stage where only the living contact with the reality of modern existence could save it from formal petrefaction [sic].’38

Sustained discussions within the AIA on the crisis of culture, combined with economic and political necessity, precipitated an important change in artists’ thinking about their role in society. The shift to the Popular Front line was followed by a surge in anti-fascist sentiment in 1936 with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. From mid-decade onwards membership to the AIA increased and it began to organise major group exhibitions, such as Unity of Artists for Peace, for Democracy, for Cultural Progress (1937) at 41 Grosvenor Square, which was accompanied by the convening of the First British Artists’ Congress. Following the lead of the American Artists’ Congress, which opened a year earlier in New York with substantial coverage in the Association’s Bulletin of April 1936 and in Left Review, the British Congress was intended to address aesthetic issues, in addition to broader questions around ‘cultural freedom’ and ‘economic security’.39 Key among the topics accorded concerted attention in the Congress’s diverse programme of exhibitions, lectures and demonstrations was the need for artists to recognise their unity with the working classes as the main bulwark against exploitation and reaction. As New Left reported, ‘for a good many English artists … [this] marked the end of the “ivory tower”’.40 Formulating objectives closely comparable to those of their American counterparts, the AIA now emphasised that the artist was a worker like any other whose jobs, skills, rights and wages should be protected through lobbying and unionisation. There was growing recognition that ‘their problems can be solved only by organizing’.41

Many other connections existed between the AIA and contemporary organisations of politically committed artists in the United States. For example, members of the English group contributed cartoons, illustrations and art criticism to Art Front, the journal of the Artists’ Union, and to the communist New Masses. Klingender was appointed a contributing editor of the former, which republished his essay for 5 on Revolutionary Art, in addition to A.L. Lloyd’s ‘Modern Art and Modern Society’ from the same volume.42 Lloyd’s thinking on art was close to that of Klingender and he too viewed modern art as potentially symptomatic of the decadence of the bourgeoisie. Art Front also published a serious, if unapologetically scathing, review of Read’s Art and Society when it appeared in 1937. Cultural critic Kenneth Rexroth, whose sentiments were shared by fellow writers Kenneth Burke and Lewis Mumford, characterised Read as a member of ‘English high bohemia’ and damned his support for ‘quaint hothouse’ modernism as ‘exceptionally exasperating’.43 The same year British and American Artists’ Congresses worked in collaboration to raise funds for the Spanish Republican forces and jointly achieved the release of thirty interned Spanish refugee artists who were given asylum in America. Also in 1937, on the occasion of the International Exhibition in Paris, AIA members worked alongside their Popular Front allies and were responsible for executing two monumental murals for the Peace Pavilion, painting the walls of the League of Nations Room and the International Peace Campaign Room. On one level these links reflect the widespread appeal of the Popular Front sentiments and, by extension, the impressive organisational skills and influence of the Communist Party; on another level, they attest to the real potential for international solidarity that existed within the cultural sphere during the 1930s.

The instrumentalisation of mural painting

It was, of course, within the highly charged atmosphere of the Paris Exhibition, with the Soviet and Nazi pavilions facing off across the Trocadero, that the artistic and political instrumentalisation of mural painting became the focus of intense debate with the unveiling of Picasso’s Guernica 1937 (fig.5). Painted for the Spanish Republic’s pavilion to mark the bombing of the Basque capital by the German Condor Legion, Picasso’s mural turned cubist fragmentation and surrealist distortion into a painted expression of rage, violence and bestiality. The mural, which drew upon a range of modernist formal techniques, was hardly a straightforward example of ‘social’ painting. It instantly became the focus of ongoing quarrels among leftists over what constituted an appropriately realist form of contemporary artistic expression. The dividing lines were drawn between those who supported surrealist and other post-cubist tendencies as a form of revolutionary art (like Read) and those who viewed them as a misguided species of escapism no longer grounded in vital social experiences (like Klingender). Similar discussions were taking place in the United States; although many American leftists had previously attacked Picasso’s modernism as a form of escapism, following the unveiling of Guernica he was hailed as ‘the greatest painter of modern times’.44 Back in Britain, Picasso’s incendiary mural – which arrived in London in October 1937 in large part due to the efforts of Read – served to intensify pre-existing anxieties within the AIA about what a ‘social art’ should actually look like.

Fig.5

Pablo Picasso

Guernica 1937

Oil on canvas

3493 x 7766 mm

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

Opposition to Read’s unequivocal praise for Guernica was summarised by Anthony Blunt in his role as art critic for the Spectator.45 Blunt was a member of the Cambridge Five, a group of spies working for the Soviet Union from sometime in the 1930s and was appointed director of the Courtauld Institute of Art after the war. His thinking on art was also heavily indebted to Antal. Blunt was a proponent of social realism and viewed modernism, despite its formal innovations, as the final stage of an individualist and subjective attitude towards art. ‘There are many kinds of painting’, he argued in an article on ‘The “Realism” Quarrel’, ‘which, at the level of painting alone, seem to be revolutionary enough, but which have no roots at all in the rising class [the proletariat]. Abstract Art and, above all, Surrealism belong to this type.’46 Blunt’s indictment of Picasso’s mural in August 1937 stands as perhaps one of the grossest miscalculations in twentieth-century art history (and one which he later publicly recanted):

The gesture is fine, and even useful in that it shows the adherence of a distinguished Spanish intellectual to the cause of his government. But the painting is disillusioning … It is not an act of public mourning, but the expression of a private brainstorm which gives no evidence that Picasso has realized the political significance of Guernica.47

If Picasso’s mural could only reach ‘a limited coterie of aesthetes’, as Blunt asserted when Guernica was shown in London, then what sort of public political art could marshal sufficient propaganda potential to serve as a model for emulation?48 Two years earlier, Blunt, who frequently entered the ambit of AIA circles as critic and speaker, had already identified a social realist artist able to meet the challenge. In the January 1935 issue of Left Review he wrote what was probably the first appraisal in Britain of Rivera, comparing him to early Italian Renaissance painter Giotto (1266–1337).49 Blunt believed that artists under socialism would occupy a position similar to those of the middle ages; painting as a unique commodity would disappear, to be replaced by more communal forms such as mural painting. Rivera’s monumental, explicitly political frescoes thus seemed to be all that a contemporary realist’s works should be. Blunt wrote two further articles on Rivera for Left Review and in 1938 he explicitly pitted the Mexican artist against Picasso. Where Picasso’s work represented a retreat into the most private inner zones of the unconscious, Rivera was a painter who assimilated the formal developments of the School of Paris but used them to create a monumental, optimistic, outward-looking public art – and Rivera managed to do this in both socialist Mexico and capitalist America. Furthermore, unlike Soviet social realism, Rivera’s was a ‘new realism’ aligned with the experiences and aspirations of the working class, yet also modern in its treatment of form and colour.50

British muralism and the Marx Memorial Library

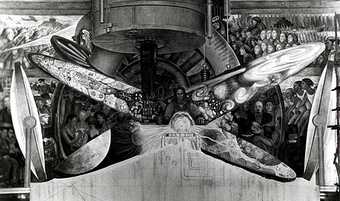

Fig.6

Viscount (Jack) Hastings

The Worker of the Future 1935

Marx Memorial Library, London

In so far as there was anything in England even approaching Rivera’s frescoes, an art which in Blunt’s words functioned as ‘the Kapital of the Illiterate’, there is one extant mural that at least comes close to fulfilling the criteria.51 While hardly capable of dissuading contemporary viewers of their preconceived notions of 1930s muralism as ‘poor art for poor people’, the fresco executed by Viscount (Jack) Hastings (the 16th Earl of Huntingdon) for the Marx Memorial Library and Workers’ College in London’s Clerkenwell (fig.6) remains one of very few public examples of social realism in England.52 The mural was commissioned for what was then the first floor Lecture Hall to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Marx’s death, and was painted in situ. The Daily Mirror featured a photograph of Hastings at work in October 1935. The image was accompanied by an interview with the artist, in which he stressed the difficulty of the process and outlined his didactic iconographical scheme for the mural, which was initially entitled An Interpretation of Marxism and later more descriptively retitled Worker of the Future Upsetting the Economic Chaos of the Present:

The large central figure, for which a Welsh miner was the model, symbolises the worker of the future upsetting the economic chaos of the present. On the left I have tried to portray the origins of the Labour movement, the Chartist movement; on the other side I show the present day Labour Movement.53

Among the figures on the left are portraits of Marx, the politician Robert Owen and the artist William Morris; on the right are Lenin and Frederick Engels. The centre of the composition is occupied by a Soviet-style worker, who is bare-chested, clean-shaven and ensconced in an orb of light; symbols of Church and State are pictured crumbling beneath his monolithic presence. Stalin is notably absent (Rivera’s Trotskyism may have influenced Hastings), and the placement of Owen and Morris on the side of Marx suggests, as art historian Alison McClean observes, a specifically British vision of socialism, one distinct from the Soviet model.54 Stalin did, however, appear a year later in Hastings’s mural Welcome to Pearl Binder for the London residence of socialist barrister D.N. Pritt, with the fresco marking Binder’s return from a sojourn in Russia.

Fig.7

Diego Rivera

Making of a Fresco, Showing the Building of a City 1931, detail showing the depiction of Viscount (Jack) Hastings and Clifford Wight

San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco

Hastings was an unlikely candidate to adopt social realist public muralism as a bulwark against modernism and the art market.55 Educated at Eton and reading history at Oxford, where he played varsity polo, he enrolled at the Slade in 1928 to study fine art under Henry Tonks. During the 1920s Tonks had done much to promote mural projects among his students, who included Evergood and Carline. In 1930 Hastings embarked on an extended painting excursion in the United States and, through his influential social network (he counted actors Douglas Fairbanks and Charlie Chaplin among his personal friends), met Rivera in California in 1931. Hastings persuaded Rivera to take him on as an assistant and received first-hand training in the fresco technique, working alongside fellow English artist Clifford Wight. Hastings and Wight are pictured on scaffolding preparing the walls in the uppermost central register of Rivera’s Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City for the San Francisco Art Institute (fig.7). Hastings subsequently travelled with Rivera to Michigan to help with the Detroit Industry 1932–3 frescoes commissioned by Edsel Ford for the Detroit Institute of Arts. Apparently an able student, Hastings himself was commissioned to paint several murals in America, including a panel for the Hall of Science at the Chicago Century of Progress Exhibition of 1933, before making a trip to Mexico on his way back to London, where he immediately joined the AIA.

Fig.8

Diego Rivera

Man at the Crossroads 1933

Rockefeller Center, New York

Hastings’s Marx Memorial mural bears superficial compositional affinities with Rivera’s 1933 fresco for the Rockefeller Center in New York (fig.8), although it offers nothing of Rivera’s virtuosity as a muralist. As Blunt observed in the Spectator, Hastings’s fresco dramatises the way ‘Rivera’s style needs transforming to suit the English situation’.56 The Rockefeller mural was well known due to the ‘fierce controversy’ it generated and Rivera was given the opportunity to publish his account of the debacle in the July 1933 issue of the Studio (although the journal was careful to preface the article by stating that it ‘has no desire to take sides’, ‘does not necessarily agree with views expressed’ and ‘has no concern with politics’). According to Rivera, the fresco fully adhered to the theme he was commissioned to interpret: ‘Man at the cross-roads of life, looks with uncertainty at the future but hopes for a better solution.’57 However, once Rivera set to work on the fresco, his corporate patrons did not approve of his vision of the future, namely socialism. A furore over proposed censorship ensued, with Evergood, Davis and Shahn organising an Artists’ Committee of Action to picket the building in protest of the Rockefellers’ failure to uphold Rivera’s right to freedom of expression. Rivera refused to alter his mural and in February 1934 its destruction incited international outrage. While the incident was a public relations fiasco for the Rockefellers, who subsequently replaced Rivera’s partisan fresco with an insipid mural by British artist Sir Frank Brangwyn on the theme of man’s search for eternal truth through Christ’s teachings, the political potential of public art was undeniable. Hastings’s mural may thus be seen as an homage to Rivera. His use of fresco and selection of strong, earthy colours reference Mexican muralism, and the monolithic worker forcefully occupying the centre and anchoring strong diagonals gives the composition and its revolutionary narrative a similar structure.

The Marx Memorial fresco hardly served as the catalyst for a vibrant tradition of social realism in Britain, to the relief of many critics and commentators. Clive Bell saw in Hastings’s work nothing ‘to interest anyone who cares for art’, while muralist Hans Feibusch hoped to be spared an ‘outcrop of monumental banalities’ or ‘pedestrian agglomerations of portraits’ that were an artistic embarrassment.58 However, what it did confirm – as was noted in the 1939 catalogue for the mural exhibition at the Tate Gallery – was that where public art was concerned ‘Great Britain has much to learn from the United States and Mexico’.59

The considerable deficiencies of Hastings’s panel are symptomatic of how fruitless it is to endeavour to create a successful mural painting without an effective patronage base. Carline concluded that England should look to the ways in which the WPA ‘saved the arts for America by establishing their basic functionalism as a structure in the framework of the nation as a whole’.60 Furthermore, he counselled that the AIA should follow the American left’s lead in developing ‘immense opportunities for exhibiting, publicising and utilising an artist’s work’.61 In 1938 Carline established an AIA sub-committee, including Black, Blunt and Klingender, to organise a show of Mexican and American social art in London.62 The shipping of Mexican works was not possible as a major exhibition was already in preparation to tour Europe, so the sub-committee decided to focus on American art, showcasing ‘US artists representing the present progressive art movement there, especially its socially conscious approach, and the results of the WPA schemes for artists’.63 Later in 1938, Black himself travelled to the United States with a group of artists and designers assigned to work on the British Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, and during this time he pursued discussions about the exhibition with Evergood, Gottlieb and Davis. More than five hundred paintings, prints and sculptures were selected by a committee co-chaired by the Artists’ Congress and the Cultural Committee of the CIO’s United American Artists’ Union. The show was scheduled to run from 10 June to 5 April 1940 at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, and subsequently to tour Britain. Carline made an additional trip to America in July 1939 to finalise plans for a catalogue to accompany the show, but he was forced to hasten home as war was now imminent. Had the exhibition been realised it would have been the most comprehensive show of contemporary American art ever seen in Britain. Although plans for the show generated great interest and enthusiasm on both sides of the Atlantic, Carline’s lavishly illustrated article ‘Fine Art in Modern America’ for the Studio in September 1940, whose coverage of social art is impressively extensive and knowledgeable, stands as the only manifestation of the artists’ considerable efforts towards Anglo-American exchange.64

1939 and beyond

The AIA was unique in the history of the cultural life of Britain in that its primary purpose during the 1930s was to organise artists to enable them to express their commitment to social responsibility and to support radical political ideas directly through their practice and activities as artists. The provision of murals for public spaces was understood as integral to achieving this mandate. The death knell had been sounded for easel painting, with an AIA members’ meeting concluding in June 1939 that ‘the only viable future for art lay in developing lithography and the mural’.65 Carline chaired an AIA Mural Committee and in February 1943 drafted a comprehensive report, followed in October with a conference, on how a national mural programme could be developed in England following Mexican and US models. The AIA’s approach to public art was subsequently embraced on the part of a previously hostile government, with officials such as Kenneth Clarke, director of London’s National Gallery and member of the wartime Committee for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts, supporting Carline’s efforts. The AIA’s newly won institutional respectability produced fairly limited and short-lived results during the war years, most notably the decoration of temporary communal canteens to ensure workers were fed during rationing.

The immediate post-war years were a tremendously fertile period for mural art in Britain. In 1951, under Clement Attlee’s Labour government, the Festival of Britain saw the execution of around one hundred murals at London’s South Bank exhibition site alone. Yet the fruits of the AIA’s efforts to politicise the role of the artist ultimately produced the very seeds of decline for its vision of socialist culture. The optimism ushered in with the post-war Labour government and the disintegration of the wartime alliance with the Soviet Union culminated in the purging of the AIA’s political objectives from its constitution by 1953 in favour of cultivating its role as a professional society firmly rooted within the established order.

The 1930s was an era dominated in both England and the United States by a concern with integrating artists into society as a whole, and muralism offered an alternative to the traditional relations between the arts, the public and the political economy. As Evergood insisted, the highest objective was the ‘prodigious feat of combining art, modernity, and humanity’, but the long-term and widespread realisation of this objective has been frustrated by history, and perhaps apathy.66 The realities of the cold war and the resurgence of the art market within a victorious capitalist democracy ensured Hastings’s The Worker of the Future was sequestered away behind bookshelves for decades, remaining untouched until its restoration in 1991. The fresco suffered the same fate as so much socially engaged art in America, whose demise was complete with the disbanding of the WPA/FAP by 1943, after which public murals were neglected and largely forgotten.