In 1964, at the time of the major exhibition 1954–1964: Painting and Sculpture of a Decade, organised by the Gulbenkian Foundation and held at the Tate Gallery in London, the British critic David Sylvester was asked by the Sunday Times Magazine how British art related to its wider international context. Sylvester responded by emphasising the partiality of his perspective: ‘I can’t help seeing it [British art] as something special and apart with which I have a personal love-hate relationship (but of course British art is a bit special anyway, rather as German art is)’.1 Sylvester was an important commentator on post-war American art at a time when it exerted a significant influence on artists in Britain. However, while Sylvester wrote with increasing enthusiasm about the vitality of recent American art from 1956 onwards, he remained acutely sensitive to the complexities of assimilating transatlantic influences. Sylvester’s advocacy of American art, starting in the late 1950s, has also tended to be overshadowed by the writing of fellow British critic Lawrence Alloway, whom Sylvester referred to in 1958 as ‘so ardent a champion of things American that he could fairly be described as a walking outpost of American civilization’.2 For instance, James Hyman’s detailed account of British art criticism in the 1950s, The Battle for Realism: Figurative Art in Britain during the Cold War, 1945–60 (2001), concluded that Sylvester, like John Berger, a fellow Brit and Sylvester’s rival in the 1950s art columns, ‘remained largely uncomprehending’ of American art.3 Hyman presents Sylvester and Berger’s shared incomprehension of American art as leaving the way clear for Alloway to take up the mantle as Britain’s leading critic of modern art. Furthermore, in Art and Pluralism: Lawrence Alloway’s Cultural Criticism (2012), Nigel Whiteley went so far as to claim Alloway as ‘the only critic who had been committed, at an informed level, to both Abstract Expressionism and Pop’.4

This article will discuss how American art featured in Sylvester’s criticism of the 1950s and 1960s, and the way in which this in turn helped to inform his thinking about contemporary British art as the continuation of a national tradition. It will focus on Sylvester’s interviews with American artists during the 1960s as a demonstration of his position as a commentator whose authority was connected to his close personal relationships with artists. The interviews provide an important resource for the study of abstract expressionism and pop art (and indeed the connections between them) and remain crucial primary sources for the understanding of American art during this period.

Encountering abstract expressionism

Born in 1924, Sylvester cut his teeth as a critic in London during the Second World War. After the war, along with contemporaries including the artists Eduardo Paolozzi, William Turnbull and William Gear, Sylvester spent extended periods of time in Paris, where he befriended artists such as Alberto Giacometti.5 In 1950, at the behest of the American critic Clement Greenberg, Sylvester was commissioned by US periodical the Nation to review the 1950 Venice Biennale. There, in the US Pavilion, he saw for the first time the art of Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, only to dismiss it as derivative of European abstract painters such as his friend Hans Hartung.6 The young critic’s review angered Greenberg, who wrote a response alleging (correctly, as Sylvester later admitted) that Sylvester was motivated by anti-American sentiment.7 Greenberg saw Sylvester’s review as an example of ‘the European View of American Art’ more broadly, concurring with New York Times art critic Alice Louchheim that European responses to the US Pavilion in 1950 were marked by both the ‘habit of Europeans to think of Americans as cultural barbarians’ and European resentment towards Marshall Plan aid.8 Incidentally, Greenberg felt that further evidence of the shortcomings of European criticism were provided by Sylvester’s enthusiasm for the work of Alexander Calder. In Sylvester’s review of the Biennale he paid Calder a dubious compliment when he described the artist as channelling ‘the essential genius of America – its capacity to make things work’.9

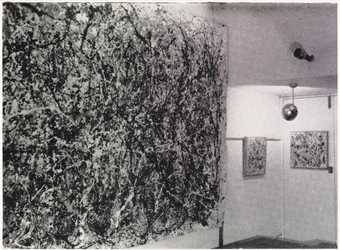

Fig.1

Installation view of Opposing Forces at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 1953, showing part of Jackson Pollock’s One: Number 31 1950

Reproduced in Architectural Review, April 1953, p.27

Photographer unknown

Opportunities for Sylvester to revise his opinion of recent American painting were sporadic in the early 1950s, since new American art was rarely displayed in Britain during this period. Pollock’s One: Number 31 1950 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), included in the Opposing Forces exhibition at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in 1953 (fig.1), was a notable exception, but even then it was not displayed favourably: the painting did not arrive from Switzerland until after the exhibition had opened, and when it did it was too big for the ICA’s Dover Street gallery and had to be shown partly rolled.10 At the same time the Independent Group were enthusiastically advocating the ‘expendable aesthetic’ of American popular culture, while Sylvester, himself a regular speaker at the ICA, began a side line in film criticism, writing essays about subjects including Marilyn Monroe and American sci-fi films.11

It was the scarcity of chances to see American work during this period that made the 1956 Tate Gallery exhibition Modern Art in the United States, drawn from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, such an important event (Sylvester referred to its effect on him as a ‘Damascene Conversion’).12 Sylvester immediately recognised the impact that the exhibition had had on the London art world, and his writing soon began to respond to it. In his first reaction he wrote:

Criticisms of the Tate’s American show suggest that some people think Jackson Pollock is a brutal, messy painter. Such critics must have been reading so much about Pollock’s practice of dribbling paint out of holes in the bottoms of tins – which certainly sounds crude – that they haven’t left themselves time to look at Pollock’s paintings and to find out that, whatever they may be or not be, they’re about as crude as Fragonards.13

Fig.2

Installation view of an exhibition featuring paintings by Jackson Pollock at Whitechapel Gallery, London, 1958

Works © Estate of Jackson Pollock

Photo © Sam Lambert

Fig.3

Opening of the exhibition The New American Painting at the Tate Gallery, London, 1959

Photo © Tate

A Pollock retrospective was held at London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 1958 (fig.2), and was the first of an important series of one-man shows of American artists at the gallery during Bryan Robertson’s tenure as director. Robertson worked with the architect Trevor Dannatt to install the exhibition, adding four low cinder-block walls to create a gallery layout that Dannatt likened to ‘a Mondrian in three dimensions’. He further divided the gallery space by running a broad strip of white carpet across the middle of the gallery and using swathes of white muslin to conceal the gallery’s high ceiling. These measures to constrict the gallery space intensified the energy of Pollock’s works and took a distinctly modern approach to the retrospective format.14 In 1959 this was followed by an even more important exhibition of post-war American art, the touring MoMA exhibition The New American Painting. This was shown at the Tate Gallery and allowed the British public to see for the first time a representative selection of work by abstract expressionists such as Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko (fig.3). The importance of The New American Painting, which was also shown at several other major European institutions, has possibly obscured reports of other exhibitions of American art in Britain at this time, particularly those held at the United States Information Service library adjacent to the US Embassy in London’s Grosvenor Square. This venue was inaugurated with the exhibition Seventeen American Artists and Eight Sculptors (31 October–21 November 1958), which not only included notable painters such as Ad Reinhardt (who did not feature in The New American Painting) but also provided a rare opportunity to see the work of contemporary American sculptors such as David Smith.

‘The New American Painting and Ourselves’

Sylvester’s writing on British artists from the late 1950s onwards began to include regular comparisons between American and British art, as in his review of the exhibition Dimensions: British Abstract Art 1948–1957 organised by Alloway at London’s O’Hana Gallery in 1957. In this review Sylvester lamented what he called ‘the family curse of British painting’, the absence of the ‘pictorial density that makes a painting, before it is anything else, a painting’ which Sylvester found everywhere in American painting. Even the ‘evanescent’ and ‘opaque’ paintings of Rothko, Sylvester wrote, possessed the ‘decisive reality of a rock-face’.15

In characterising British art in this way Sylvester was echoing (albeit in relation to more recent art) Nikolaus Pevsner’s 1955 Reith Lectures on ‘The Englishness of English Art’, which asserted a connection between art and national character.16 Pevsner concluded that ‘what English character gained of tolerance and fair play, she lost of that fanaticism or at least that intensity which alone can bring forth the very greatest in art’, and echoes of that sentiment can be found throughout Sylvester’s writings of the 1950s and 1960s.17 After all, Sylvester had by this time organised exhibitions of work by Henry Moore (at the Tate Gallery as part of the 1951 Festival of Britain) and Stanley Spencer (at the Arts Council Gallery on St James’s Square in 1955), two of the artists from this period that are most often discussed in relation to British national identity. The critic was therefore implicated in the ongoing development of the ‘English character’ of which Pevsner spoke.

In 1959, in response to The New American Painting, Sylvester made his most extensive statement yet, in the BBC Third Programme broadcast ‘The New American Painting and Ourselves’.18 Here Sylvester praised critic Harold Rosenberg, Greenberg’s bête noir, stating that his expression ‘Action Painting’ was ‘beautifully appropriate to this kind of painting, since what the painting is about is largely the act by which it was created’.19 Alloway had also championed the seminal 1952 essay ‘The American Action Painters’ in which Rosenberg set out this idea, and as a result Greenberg named Alloway one of the culprits in his anti-Rosenberg essay ‘How Art Writing Gets Its Bad Name’ (1962).20 Rosenberg had claimed that ‘the new painting calls for a new kind of criticism, one that would distinguish the specific qualities of each artist’s act’.21 Sylvester, however, went further in his criticism, not only identifying but in some sense re-enacting those acts:

As I look at a Kline I continue the painter’s struggle to bring the black and white into a single plane … in looking at a Guston I respond to the extraordinary amount of passion which has been compressed into each and every firm, decisive yet reserved stroke of the brush on the canvas, I relive the series of decisions that each mark should be just where it is. Looking at a Pollock I go back over the traces of his gestures, those gestures which manage to have at one and the same time a sort of Dionysian abandon and yet never to lose control.22

In an article surveying the (mostly negative) responses to The New American Painting in the British media, Alloway accepted that Sylvester’s talk was an exception that ‘worked conscientiously at the aesthetic problems raised by American art which everybody else missed or shirked’.23 Nonetheless Alloway disagreed with Sylvester’s approach, exemplified by the quotation above, which he thought ‘seems to be little more than an updating of BB’s [Bernard Berenson’s] empathy for Renaissance form displaced to paint’.24 The interesting similarities and differences between the criticism of Alloway and Sylvester deserve further research, but for the present essay the most relevant aspect of Alloway’s criticism is that while he accepted an absolute distinction between artist and spectator (with all the independence from the artist’s intention that this implied), Sylvester’s criticism was always rooted in the artist’s process and intention as a starting point. As Sylvester said in an interview towards the end of his life, ‘if there’s a method in my work, it is to work out the relationship between the artist’s conscious and unconscious intentions’.25

Transatlantic interchanges

In the late 1950s British artists and writers of Sylvester’s generation visited the US with increasing regularity, with Turnbull (1957), Alloway (1958), sculptor Anthony Caro (1959) and artists Harold Cohen and Richard Smith (both 1959–61, on Harkness scholarships) among those who spent time there. Painter Malcolm Morley, meanwhile, emigrated to the US in 1958.26 Sylvester himself first visited America in 1960, as part of the same US State Department programme that had brought Alloway there two years earlier, while Sunday Times art critic John Russell also went as part of the programme in 1960.27 On his trip Sylvester interviewed six artists in New York, as well as interviewing Stanley Kubrick in Los Angeles.28 Interviewing contemporary American artists became a regular part of Sylvester’s work and by 1968 he had interviewed nineteen, including Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella and Robert Morris.29 During his time spent in the US Sylvester also developed relationships with critics such as Thomas Hess and Max Kozloff with whom he would regularly record radio talks on the BBC in the 1960s, discussing issues such as the distinctive characteristics of American art.30

Sylvester’s importance as an interviewer of artists has been widely acknowledged. Artist Rachel Whiteread, for instance, described him as ‘an extraordinary interviewer, the best I’ve ever encountered’.31 Meanwhile, Hans Ulrich Obrist, perhaps the most prolific contemporary interviewer of artists, has acknowledged the influence of Sylvester’s American interviews (which he described as a ‘portrait of a city’) on his own practice.32 In recent years the artist interview has become a ubiquitous component of art magazines, exhibition catalogues and events programmes, but in 1960 artist interviews were comparatively rare, particularly those undertaken by well-known critics such as Sylvester. Alloway, for instance, noted ‘the neglect of interviews which characterizes art criticism’ and acknowledged their value as documents, although he rarely conducted them himself.33

Sylvester’s interviews were very different from both oral history and journalism, both of which offered methodologies for interviewing artists at this time. In 1958 the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art instigated its Oral History Program, directed by Paul Cummings, who noted in the introduction to a book of his interviews that ‘the unstructured interview was developed at Columbia University after World War II for the purpose of recording the memoirs of political and military figures’.34 Elsewhere the interview was approached primarily as a form of journalism and was rarely practiced by leading critics (in the Anglo-American context the American critic Irving Sandler is perhaps the closest comparison to be made with Sylvester at this time).35 Books of artist interviews in the English language from this time were made by interviewers such as Selden Rodman, Edouard Roditi and Noel Barber – novelists and poets who interviewed artists from the perspective of an inquisitive amateur rather than the informed critics and art historians usually tasked with interviewing artists in more recent times.36

Sylvester’s dialogues resemble more closely the famous Paris Review interviews with authors that began in 1953, focusing their attention on the practicalities of the artist’s work and routine. As is demonstrated by the quotation given above from ‘The New American Painting and Ourselves’, Sylvester’s experience of looking at these paintings was inseparable from his sense of the artist creating them, as understood through their actions rather than their biography. This drove Sylvester’s line of enquiry in his interviews, which, rather than consisting of a succession of prepared questions, often moved into very detailed (and occasionally pedantic) exchanges about the artist’s process and intentions. For instance, he asked Franz Kline a string of clarification questions about whether the artist encouraged or suppressed figurative images that emerged inadvertently in his paintings.37 As a result the interviews often have a strong sense of Sylvester trying to understand the process in detail, which connects clearly to the way he wrote about the experience of artworks throughout his career.

The BBC was beginning to embrace the interview format in the late 1950s, with John Freeman’s famous Face to Face television interviews (1959–62) a landmark in the genre. Freeman, however, was interviewing some of the best-known personalities of the day, and the artists interviewed on the programme (Henry Moore, Augustus John and Cecil Beaton) needed no introduction. Sylvester, on the other hand, was interviewing artists whose works had been exhibited rarely, if at all, in Britain at the time. Sylvester gave much of the credit to Leonie Cohn, a talks producer for the Third Programme who since 1951 had produced many of Sylvester’s work for the station, and who, as Sylvester stated, ‘persuaded her superiors that lengthy interviews with American artists were of serious interest to a British audience and who was also mainly responsible for editing the broadcast versions’.38 Many of Sylvester’s interviews appeared on ‘Comment’ (subsequently ‘New Comment’), the Third Programme cultural magazine that BBC producer Philip French described as ‘the beginning of topical interviews on the Third’.39 From this point onwards the BBC was sufficiently convinced of the value of artist interviews that in 1965 an interview between Sylvester and Giacometti was broadcast in the original French-language recording.

Another significant difference between Sylvester and contemporaries such as Rodman and Katharine Kuh (author of the 1962 book The Artist’s Voice: Talks with Seventeen Modern Artists) was that whereas the latter group insisted that they had documented their conversations verbatim, even where they had not been tape-recorded, Sylvester’s interviews were extensively edited both for radio broadcast and for subsequent publication. Transcripts of Sylvester’s interviews show that this was often necessary to make programmes suitable for broadcasting from the somewhat rambling interviews with, for instance, Kline and Robert Rauschenberg (the latter taking place over two sessions). The artists often hesitated, spoke indistinctly or trailed off mid-sentence. As a result, the published interviews in particular (often re-edited by Sylvester from the radio interviews, which were themselves edited versions of the original interviews) are a long way from the awkwardness and confusion that often comes out in the transcripts. This approach was very different to that employed in the early days of the Third Programme, which initially insisted on all programmes, including interviews, being scripted.40

Learning from New York

Shortly before the 1960 interviews were broadcast, Sylvester’s first account of his time in New York was published in the New Statesman under the title ‘Success Story’. Here Sylvester discussed the effects that recent success had had on the abstract expressionists (and what this meant for the next generation of New York artists). Sylvester was impressed by what he saw as the democratic, unpretentious attitude of New York artists (partly because ‘New York just is not lousy with class-consciousness’),41 and contrasted the continuing presence of established artists at the famed cultural meeting-place ‘the Club’ with the lack of interest shown by artists in the closest London equivalent (‘how often do you see an established artist amongst the audience of culture-vultures at the ICA?’). Sylvester considered this communal spirit ‘one symptom of the New York artist’s freedom from the London affectation that it’s infra dig to talk about art, that the only really permissible topic of conversation is the behaviour and motives of one’s friends’. On the other hand, he did add the caveat that ‘London artists, when they do let themselves go about art, tend to be more articulate and subtle about it’.42

If not a provocation for London artists to display their articulacy more often, this might have been a gesture of appeasement to those British artists Sylvester described earlier in the article as producing ‘wax fruit’ as compared with the ‘fresh fruit’ of American art.43 The latter is more likely, especially since the following year Sylvester wrote an essay, ‘Horses’ Mouths’, in which he criticised recent interviews and statements by British artists, particularly Frank Auerbach, Richard Hamilton and Robin Denny. Sylvester claimed that Auerbach, who described an artist as ‘the sole coherent unit’, was identifying himself with ‘Cézanne and the ageing Rembrandt, or rather with a Hollywood idea of them’. Meanwhile, texts by Hamilton and Denny enthusing about modernity and popular culture were accused of an ‘embarrassing lack of historical perspective’.44 Sylvester’s argument was that all three artists were making inaccurate generalisations based on preconceived ideas, and that ‘artists’ statements become useful rather than blushmaking when they are not ambitiously theoretical but simply autobiographical’.45 Attentive readers of Sylvester’s work would have recognised the implication that it was the American artists he interviewed who provided these ‘simply autobiographical’ responses.

Sylvester was not the only critic to distinguish between American and British artists at this time. The writer Al Alvarez, who regularly appeared alongside Sylvester on BBC Home Service programme ‘The Critics’, broadcast a series of features on the Third Programme between 1961 and 1964, which were subsequently published as the book Under Pressure: The Writer in Society: Eastern Europe and the U.S.A. (1965). In Under Pressure, similar contrasts to those made by Sylvester were drawn by several writers familiar with both British and American culture. Most specifically, the poet Robert Lowell is recorded as saying:

I feel that we [Americans] have a feeling the arts should be all out. If you’re in it, you’re all out in it and you’re not ashamed to talk about it endlessly and rather sheerly. That would seem embarrassing to an Englishman and inhuman probably, to be that all-out about it. I guess the American finds something uninvigorating about the Englishman in that he doesn’t plunge into it.46

Sylvester’s friend Elinor Bellingham-Smith, whose painting he greatly admired, wrote to him after hearing the interviews: ‘I sometimes think that if I’d been an American things might have been better … listening to those American painters talking to you made me feel in great sympathy with them’.47 Such was the influence of abstract expressionism on British painting by the early 1960s that Sylvester wrote an article describing it as ‘A New Orthodoxy’, which suggested that there was still an urgent need for more exhibitions in Britain showing a diverse range of American art.48 Even long after the interviews had taken place they remained relevant for artists. The Royal Academician Christopher Le Brun, for instance, has acknowledged the effect that the interviews had on him when he was studying at London’s Slade School of Fine Art in 1970–4. Le Brun’s tutor Malcolm Hughes used the interviews as pedagogical aids, and Le Brun has acknowledged that the interviews encouraged him to become more open to the resources of the unconscious.49

Double-negative capability

Sylvester’s interviewing technique may have been particularly well suited to artists whose practice involved a particular emphasis on chance and impulse, which again aligned it with ‘the new American painting’. In 1959, shortly before his first visit to the US, Sylvester made the broadcast ‘Three Painters on Painting’, which included interviews with British artists Peter Lanyon and William Scott (whose images were based on the experience of place and the depiction of still-life objects respectively) and Alan Davie, who described his work as the ‘exploration of a pictorial idea’ with no basis in reality.50 The individual interviews were followed by a discussion between all four men. After hearing the recordings Lanyon wrote to Sylvester: ‘I feel depressed because I realise that only my own painting can explain and that it will not communicate because the Art international, New York School etc are geared to a concept very close to Davie’s. Here am I talking of communication but unable to do so while Alan caring less for communication, does so.’51 Despite his misgivings about Davie’s art, Lanyon felt that its premise could be verbalised more effectively than his own.

Sylvester’s patient probing was undoubtedly more suited for discussion with an abstract artist such as Kline than was the approach of interviewers like Kuh, who asked blunt questions such as ‘Is there any symbolism in your paintings?’. However, Sylvester’s interviews all shared the common objective of exploring ‘the relationship between the artist’s conscious and unconscious intentions’.52 After interviewing Lichtenstein, for instance, Sylvester specifically noted the way that the cool assertiveness of the artist’s paintings (‘like glugging a quart of quinine water followed by a Listerine chaser’, in Kozloff’s memorable description) contrasted with the way Lichtenstein discussed his work:53

I have been very much struck by Lichtenstein’s constant tentativeness … With Pop Art … it might be supposed that the artist, before he starts painting any painting, knows exactly what he’s trying to do. But Lichtenstein did not know what he was trying to do – for all the acuity of his intelligence – did not quite know what he was aiming to achieve in terms of form, was far from being sure what his attitude was towards his subject matter.54

The same tentativeness was evident in Sylvester’s interview with de Kooning, which Hess saw as setting out a method of ‘“double-negative capability” (nothing is excluded, nothing is ever allowed to be pinned-down)’.55 Sylvester, however, was irritated by the way that Hess and Rosenberg edited the interview into a monologue for publication in their journal Location, removing Sylvester’s questions and propositions. The monologue, Sylvester wrote, was a form ‘which was imposed upon it by the de Kooning Mafia [Hess and Rosenberg] and which I, as a newcomer to their territory, felt too scared to reject’.56 Sylvester objected because he felt the elimination of the questions made de Kooning’s statements ‘sound less hesitant, less tentative than they were – makes them sound glib’.57

Divided loyalties

It is quite possible that Sylvester’s famous interviews with Francis Bacon, the first of which was made following the artist’s 1962 Tate Gallery retrospective, were in some way inspired by the de Kooning interview. Both artists, in Bacon’s words, trod ‘a kind of tightrope walk between what is called figurative painting and abstraction’, and both were unusually articulate and engaging interviewees.58 Cohn again seems to have played a crucial role in instigating the first interview with Bacon. She suggested the idea to Sylvester (who doubted that Bacon would agree to take part) and subsequently produced the interview.59 Sylvester, who was a close associate of Bacon in the early 1950s, had seen little of him since 1958, when ‘his new paintings had seemed so shockingly bad that I felt totally disillusioned about him’.60

There was also a second reason why Sylvester had stopped seeing Bacon, which was his irritation at Bacon’s dismissive attitude towards American abstract art.61 During that same period de Kooning replaced Bacon in Sylvester’s pantheon, to the extent that when in 1962 he wrote of ‘the three great human-image-makers of the generation born in the early years of the century’, Sylvester was referring to Giacometti, de Kooning and French artist Jean Dubuffet.62 One reason why Sylvester doubted that Bacon would consent to being interviewed by him was that he was not sure Bacon would have liked his review of the Tate retrospective. In it Sylvester responded positively to the exhibition, but wondered ‘whether Bacon’s paintings are great art (as de Kooning’s figure-paintings, with which they can most closely be compared, are great art)’.63

While Bacon was invariably disdainful of American art, Sylvester believed that he paid closer attention to it than he was prepared to admit. After Bacon’s death Sylvester suggested that he could have been influenced by works by Rothko and Barnett Newman exhibited in The New American Painting in 1959, and that resemblances to them ‘often occurred in Bacon’s backgrounds and settings, and went on doing so’.64 It seems equally possible that Bacon could have listened to Sylvester’s American interviews and that these could in turn have influenced his decision to record his own with the same producer and interviewer. Certainly, the amount of editing that Bacon’s interviews required was more substantial than any of the American interviews, as the transcripts in Sylvester’s archive confirm.65

Along with Bacon, Sylvester interviewed a handful of other British artists for the Third Programme during the 1960s – Moore, William Coldstream, Robert Medley and Rodrigo Moynihan – although far fewer than the nineteen Americans he interviewed during the same period. These British artists were born in the early years of the twentieth century (or in Moore’s case, the tail-end of the nineteenth) and were well into middle age. This was also true of the Americans Sylvester interviewed in 1960, although in their case the fact that they had not been interviewed in the British media before (owing to the rarity of British critics visiting the US for much of the 1950s) gave those interviews a cachet and interest lacking in the British interviews. In a sense, then, Sylvester was playing catch-up in his first set of American interviews, but over the next few years he interviewed younger American artists including Jasper Johns, Helen Frankenthaler, Frank Stella and Larry Poons (all of whom were thirty-five or under at the time), while conspicuously not interviewing British artists of the same generation such as David Hockney. Indeed, the BBC invited Sylvester to interview Auerbach (then thirty years old) in 1961, but Sylvester turned down the proposal.66 Shortly afterwards he wrote ‘Horses’ Mouths’ in which he contrasted ‘Auerbach’s half-baked public utterances with the quality of his actual work’.67

As Hyman showed in The Battle for Realism, Sylvester had been closely associated with the so-called School of London in the 1950s (a group that loosely consisted of Bacon, Auerbach, Michael Andrews, Leon Kossof, Euan Uglow and Lucian Freud), but tellingly he never interviewed any of these artists except Bacon. By the 1960s Andrews, who in 1957 Sylvester was talking up as ‘possibly a greater painter’ than Bacon, believed that British artists Sylvester had supported felt betrayed by his advocacy of American art.68 After leaving the New Statesman in 1962, Sylvester joined the Sunday Times Magazine (the first of the colour supplements based on American magazines) as a writer and editorial advisor, providing him with a prominent platform to help shape the narrative of 1960s British art. Essays he wrote for the magazine such as ‘Dark Sunlight’ (1963) and ‘New York Takeover’ (1964, at the time of 1954–1964: Painting and Sculpture of a Decade) were accompanied by lavish photographs of the artists and their work, adding a visual interest conspicuously lacking from the art columns in the New Statesman. Something of the importance attached to these essays within the artistic community can be glimpsed from a letter that Moynihan’s wife Anne wrote to Hess, responding to Moynihan’s omission from ‘Dark Sunlight’. Anne Moynihan wrote: ‘I realize one can’t fight monopolies or pressure groups or anything else, but I think in this case someone should comment on the omission, as I feel that not only is he the best abstract painter in England, but he was also the intelligence behind many movements.’69

In ‘Dark Sunlight’ Sylvester reaffirmed his belief that not only were Coldstream and Bacon Britain’s outstanding painters (with Auerbach receiving the most praise of younger British artists), but that the ‘amateur’ approach of Coldstream and Bacon (working for themselves, not their audience) set an example younger artists would do well to follow.70 At this time Sylvester was still uncertain about the lasting value of pop art (‘the subject matter is so attractive to me that I can’t tell how long the attraction will last once the subjects aren’t up to date’).71 Sylvester wrote two of his occasional catalogue prefaces during the early 1960s for exhibitions in London of the work of Jack Smith (Matthiesen Gallery, 1960) and Henry Mundy (Hanover Gallery, 1962), both of whom worked in the ‘pale, misty colours, such as greys, greyed-down blues and greens, pale browns, dirty whites’ which typified for the critic the continuing ‘mainstream’ of British painting.72 ‘Dark Sunlight’ also angered young British artists, several of whom (including Denny, Caro, Roy Ascott, Richard Smith and Bernard and Harold Cohen) signed a letter accusing Sylvester of ‘trying to drag British art back into the suffocating club atmosphere of amateurism and dilettantism at a moment when, for the first time in this century, a generation of artists has deliberately taken up a position outside it and against it’.73 What Sylvester considered an independence and individuality that distinguished leading British artists they could only see as provincial, presenting art as a gentlemanly hobby rather than a career.

The wistful dream of British pop

Sylvester had begun ‘Dark Sunlight’ with the assertion that ‘British painting always inclines to have a somewhat forced, unnatural air, like ladies’ cricket or hip clergymen’.74 However, seeing the exhibition British Painting in the Sixties at the Tate Gallery and Whitechapel Gallery that year changed Sylvester’s mind, as he showed in a short Sunday Times Magazine article on ‘The Year in Art’.75 Sylvester noted a ‘new confidence’ and ‘hip awareness of what is going on in the art world outside’ that was previously lacking, and used the letter from Caro et al in response to ‘Dark Sunlight’ as proof of this new mentality: ‘what the letter showed … was that here we have artists who don’t care for the Englishness of English art, are no longer disposed to be oddballs in the international art world’.76 At this point Sylvester, whose article started and finished by saying British art was second only to American and that ‘the best place to be now if you can’t get to New York, is London’, seemed to be leaving behind his own insistence on the ‘Englishness of English Art’ in favour of a commitment to a more outward-looking perspective in keeping with that of the pop artists.

Less than a month later Sylvester’s important Sunday Times Magazine essay ‘Art in a Coke Climate’ was published, in which the critic gave equal coverage to British and American pop artists and offered a persuasive analysis of pop art within the tradition of western painting. Beginning with a contrast between wine culture (artisanal, individual, durable) and Coke culture (standardised, mass-produced, expendable), Sylvester concluded with the affirmation that however much pop art drew from Coke culture, ‘a reverence for the unique object is, I take it, the basic moral assumption of a wine culture, which is the kind of culture to which art can’t help belonging’.77

Even though artists from both sides of the Atlantic were brought together in the article, however, Sylvester continued to insist upon a clear distinction between British and American pop. Using similar terms to his 1957 review of Alloway’s Dimensions: British Abstract Art 1948–1957, Sylvester wrote that compared with the matter-of-factness of American pop, ‘most of British Pop Art is a dream, a wistful dream of far-off Californian glamour as sensitive and tender as the pre-Raphaelite dream of far-off medieval chivalry’.78 He demonstrated this with a comparison of works by Paolozzi and Jasper Johns which both used target imagery: ‘in terms of sheer originality, Paolozzi is one of the most inspired artists of his generation anywhere. But that old British amateurishness stops him short, where an artist like Johns goes beyond inspiration into rigorous thinking and painting’.79 Again there is a parallel in Under Pressure, which Alvarez concluded with a discussion of ‘energy’ as an ‘ambiguous virtue’ of American art: ‘This may at times seem battering, bull-headed and – for the arts – paradoxically insensitive. [Robert] Lowell, with some irritation, calls it a “monotony of the sublime”. It strikes me as preferable to the Englishman’s habitually wan caution and cult of the amateur.’80

No doubt Sylvester, one of the most patient and attentive of viewers, believed that his distinctions were based on careful looking, augmented by artists’ accounts in interviews, rather than any a priori point he wished to prove. But Sylvester’s ambivalence, oscillating between affirmation and caution, might also be connected to his failure to obtain the job as a New York art critic which he craved, as a result of which he remained in London while Alloway, for instance, moved permanently to the US in 1961. It was this rootedness that distinguished Sylvester from the ardent internationalism of critics such as Alloway and meant that while appreciating the quality of new American art, he affirmed a resilient core of identity rooted in place. As Sylvester said in a discussion about 1954–1964: Painting and Sculpture of a Decade:

Right at this moment, as we’re talking, I can think of five leading New York artists who are in London. There’s continual contact, quite apart from the art magazines and the exhibitions. Yet London is London and New York is New York. There’s a terrific impermeability of place to the influence of ideas. It is reassuring … The work of artists here today is very New York-influenced. And yet it remains, in spite of everything, something that belongs here.81

The signs of transatlantic exchange in Sylvester’s writing of the late 1960s are more subtle than in his earlier writings. In the catalogue he wrote for the 1968 Henry Moore exhibition at the Tate Gallery, for instance, it seems clear that Sylvester had American artists such as Claes Oldenburg and Jim Dine (both of whom he had interviewed) in mind when writing about ‘Hard and Soft’ aspects of Moore’s work.82 Sylvester worked on this catalogue while teaching for a year at Swarthmore College, Pennsylvania, and thanked his students for contributing ‘certain interpretations of Moore’s imagery’ to the book.83 For a critic so deeply invested in the relationship between British and American art it seems fitting that the culmination of Sylvester’s work on Moore, an artist so strongly associated with British national identity, incorporated his experience of America and its art in this way.84 While Sylvester continued to keep abreast of new developments in American art (as shown by his ongoing interview series), his withdrawal from regular criticism at the end of the decade helped to clear the way for a younger generation of writers such as Charles Harrison to document the exchanges between British and American artists in the 1970s.