'I tried to push him down the stairs': John Berger and Henry Moore in Parallel

Tom Overton

John Berger is known for his trenchant criticism of what he saw as Moore’s overblown reputation in the 1950s and 1960s, but, as this essay explores, Berger respected Moore as a person and in the 1980s admired his later work.

In 1988, two years after Henry Moore’s death, the art critic Peter Fuller ended his affiliation with and allegiance to his mentor John Berger with an essay for New Society titled ‘The Value of Art’. Here he claimed that Berger had made his name as a young critic in the early 1950s through ‘outspoken, even hysterical attacks’.1 Fuller alleged that Berger had ‘denigrated the spiritual vision of Henry Moore’, dismissed Moore’s work as ‘Piltdown sculpture’ (in reference to a notorious case in which modern human bones were fraudulently presented as prehistoric) and advocated instead ‘a pedestrian social realism’.2 Two weeks later, New Society printed Berger’s first response to Fuller’s claims, ‘The Confession’:

Yes, I hated Henry Moore. It is true that I wrote things like ‘Moore’s work represents effectively and truthfully the modern artist’s struggle to achieve vitality ...’. But this was a feint, an alibi, for, once when Henry and I were teaching in the same life class, we went out during a break to talk, and I tried to push him down the stairs. His life was only saved by a plaster cast of Michelangelo’s Slave. And indeed, it was from this moment onwards that I began to hate the enslaved and exploited.3

Had they not noticed the incongruous note of slapstick, Berger’s regular readers would have been alerted to the intended sarcasm by the claim ‘to hate the enslaved and the exploited’: his writing had always aimed to reconcile what the author and editor of Berger’s essays Geoff Dyer later called ‘the enduring mystery of great art and the lived experience of the oppressed’.4 Berger responded again to Fuller in his 1989 article ‘A Sense of Touch’, which looked sensitively and sympathetically back over Moore’s career and his own responses to it, showing that ‘The Confession’ had been sarcastic in intention. This essay seeks to chart Berger’s varied responses to Moore throughout his long career, setting these within the broader context of their lives and suggesting that their respective achievements should be seen as mutually illuminating rather than antagonistic.

Chelsea Polytechnic

After completing his military service and using an ex-serviceman’s grant, Berger (born 1926) enrolled at what was then the Chelsea Polytechnic in 1946 with the aim of becoming a painter. Moore had founded the sculpture course there in 1931 and helped restart it when the college reopened in 1945.5 Although his teaching commitments diminished as demand for his work grew, Moore continued to teach at Chelsea in a visiting capacity until the early 1950s, and Berger attended Moore’s drawing classes.67 Around 1947 Berger took a teaching position at the school and led classes that Moore occasionally visited.8 Berger later recalled that Moore would remain ‘very silent’, watching a student at work before doing ‘another diagram to show how to do it’ with the craft of ‘a shoemaker teaching shoemaking’.9

This crossover of careers, however, was short-lived as Berger devoted an increasing amount of time to writing. On the basis of his scripts about paintings in the National Gallery for BBC radio programmes, he secured a regular column at the left-leaning Tribune (a newspaper that, incidentally, Moore supported by donating money and artworks to be sold to raise funds),10 and by 1952 was considered by the staff and students at Chelsea to be primarily a writer in the employment of the New Statesman.11 As he later explained:

with the issues of war and peace and the threat of nuclear war, particularly before the Soviet Union had achieved nuclear parity, it seemed to many of us that the world had only a few years to survive and so the urgency of political statements, political action and propaganda was enormous. Painting seemed a very indirect way of contributing to that whereas words seemed not all that effective but rather more so. This, I rationalised to myself, was why I gave up painting. I threw myself into journalism about art but also about political issues, into political activity, into meetings. Then, as time went on, I became so engaged that the return to painting, although remaining a dream which I still have, became impossible.12

This position goes some way to explaining the sharp-edged, polemical tone of some of Berger’s writings and in particular his thoughts on what was at stake when an artist of Moore’s prominence did not directly engage with these issues.

Employing the yardstick ‘does this work help or encourage men to know and claim their social rights?’, Berger struggled in his critical writings to define a space for a realist art that opposed the conservatism of Soviet socialist realism, rejected the taste represented by the Royal Academy and stood apart from the newly fashionable American art (he associated this with US propaganda).13

While Berger’s political commitments were clear and confrontational, Moore's political positions varied over his career. In a survey undertaken in 1934 by the Unit One group Moore declared that his ‘greatest sympathies lie towards Communism’. In 1950 he declined a knighthood but five years later he accepted the Companion of Honour and then, in 1963, the Order of Merit.14 His move away from political radicalism as he aged was hardly unusual, but it was a key factor in allowing his work to be seen not just as politically neutral but supportive of a centrist and politically conservative position.15 According to art historian Julian Stallabrass, the post-war state required an ‘ideal model of the family’ and Moore’s ‘unusual mix of human content and avant-garde style could serve as a suitable expression of the caring technocracy of modern democratic socialism’.16 In 1948 Moore shared the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale with the nineteenth-century master J.M.W. Turner and won the International Sculpture Prize. Thereafter the British Council’s Visual Arts Department promoted his work around the world for the purposes of cultural diplomacy, and his apparently centrist politics facilitated this process.

‘Public Sculpture’ and ‘Fashionable Blinkers’ 1953

By 1953 Moore’s work had become synonymous with what Berger in an article of the same year called ‘the general taste of most official and semi-official bodies, such as the British Council, the Acquisitions Committee of the Tate Gallery and the I.C.A.’, to which he was happy to declare himself ‘opposed’.17 Both men were still listed as colleagues in the Chelsea Prospectus,18 but this did not deter Berger from using his column in the New Statesman and Nation to dismiss Moore’s new screen for the Time-Life building as ‘crudely speaking, too highbrow’ and a ‘positive failure’ (fig.1).19 There was barely an angle, he claimed, at which it did not either uselessly obstruct the street or hide its own details. The accompanying bronze reclining figure was ‘neither relaxed nor in the act of getting up, but between the two – as though reluctant to continue sitting in a puddle.’20 However, Berger’s damning verdict on the building – ‘a marvellous example of the commercial sham to which culture-mongering paradoxically leads’21 – suggested that he was responding to the work, and the structures of its production, rather than the artist per se. In ‘Fashionable Blinkers’, a review of a display of recent acquisitions at the Tate Gallery published in August 1953, Berger described one of Moore’s works – probably the Ancaster stone Girl 1931 (fig.2), acquired in 1952 – as among the few ‘probably really worth acquiring’.22

Henry Moore

Time-Life Screen 1952–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Errol Jackson

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Time-Life Screen 1952–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Errol Jackson

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Girl 1931

Ancaster stone

object: 737 x 368 x 273 mm

Tate N06078

Purchased 1952

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore OM, CH

Girl 1931

Tate N06078

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

‘Piltdown Sculpture’ 1954

In February 1954 Berger published a review of a Leicester Galleries exhibition of thirty new bronzes, large and small, by Moore.23 Although it is by no means Berger’s best piece of writing on Moore, the article ‘Piltdown Sculpture’ had enormous impact. As has been seen, it was quoted by Fuller three decades later, and, as late as 2003 Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell suggested that the field had still not ‘shaken free’ from ‘John Berger’s critical attack in the 1950s on Moore’s commitment to “truth to material” as his only subject and consequent production of “Piltdown sculptures”’.24

As in ‘Fashionable Blinkers’, Berger praised Moore’s works of the 1930s. Moore was ‘a craftsman of extraordinary sensitivity and feeling’, whose ‘early figures and abstract pieces, worked according to the theory of “truth to material”, are very pleasing objects, satisfying to handle and interesting for revealing the nature of the stone or wood’. But, he continued, ‘an artist must do more than create an object. A craftsman creates an object – usually one that can be used. An artist creates an image. An object is simply itself. An image connects and is a comment on something other than itself.’25 He went on to critique not only Moore’s process of working but also the complacency of the times. Just as the discovery of the fraud surrounding the archaeological remains of the ‘Piltdown Man’ in November 1953 demonstrated that there had been a good deal of wishful (and even nationalistic) thinking behind their acceptance as an important find, Berger saw Moore’s work as ‘a tragic example of how the half-truths, on which so much Modern Art has been based, eventually lead to sterility and – in terms of appreciation – mass self-deception.26 The exhibition, Berger argued, represented the opposite of what he meant by ‘knowing and claiming one’s social rights’, and it was all the more depressing in his estimation ‘because Moore is so obviously an honest-minded artist.’27

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954

Bronze on wooden base

object: 530 x 270 x 345 mm, 16 kg

Tate T00389

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore OM, CH

Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954

Tate T00389

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

For Berger, Moore had been swept up in what he called ‘the present sentimental, highbrow fashion for projecting crises of conscience and introspection on to the timeless processes of nature’, noting that in ‘some way it is a comfort to lose oneself in aeons, to hide oneself under the rock of ages – perhaps rather as it is a comfort to leave all the troubles of the world to “Evolution”’.28 The most prominent expression of this fashion – for Berger, a form of political quietism – was the now famous catalogue essay for the New Aspects of British Sculpture exhibition in the British Pavilion at the 1952 Venice Biennale. There the critic Herbert Read suggested that a new generation of British sculptors, including Kenneth Armitage, Reg Butler, Lynn Chadwick, Eduardo Paolozzi and Robert Adams – with Moore as ‘the parent of them all’ – was linked by an awareness of working in the shadow of a potential nuclear holocaust.29 ‘These new images belong to the iconography of despair’, Read claimed. ‘Here are images of flight, of ragged claws “scuttling across the floors of silent seas”, of excoriated flesh, frustrated sex, the geometry of fear.’30 As the art historian David Cohen has pointed out, ‘one of [Moore’s] most abrasive and disturbing images’, Mother and Child 1953 (fig.3) came out of this period’s idiom: ‘the spindly, tortuous quality of the piece’s surfaces share something of the brutalism and open form of the young sculptors working in forged metal.’31 Berger was accordingly unsympathetic to this piece in ‘Piltdown Sculpture’, describing it as ‘a mother with simplified legs but a wrench-spanner for a head hold[ing] back her child who is trying to bite off her breast with his beak – he has presumably succeeded once, for her other breast is hollow!’32 (Significantly, perhaps, Berger was not alone in thinking that Moore’s recent bronzes represented a decline in his powers. After criticising, as Berger had, Moore’s King and Queen 1952–3, the psychologist Erich Neumann, for example, wrote in 1959: ‘Already in this pair we sense a peculiar barrenness, a loosening of the tie with the creative depths, which is even more evident in the archetypal Mother and Child from 1953.’33 In 1968 the critic David Sylvester similarly expressed negative views, arguing that, ‘Oblique, half-hidden images of aggressive eating are recurrent and powerful in Moore’s work, but brought into the open the image seems gratuitous’.)34

The article had an explosive effect. Berger later described how a representative of the British Council ‘actually telephoned the artist to apologise for such a regrettable thing having occurred in London.’35 The minutes of the Council’s Fine Arts Committee do not record a mention of any such call, or who made it,36 but the closeness of the ties between staff of the British Council and Moore in the period makes such a gesture seem possible.37 ‘Piltdown Sculpture’ had ended by commending the work of Raymond Mason, which Berger had pointedly described as ‘concerned with men striving in their environment – instead of sinking back into it and emulating fossils’,38 and Mason remembered receiving a telephone call from the Arts Council in which he was advised to apologise to Moore, though he himself had done nothing.39

In the letters pages of the New Statesman the debate about Berger’s article ran until 6 April, with the editors apologising that ‘only a small selection’ of the letters they received could be published.40 In one, the painter and writer Patrick Heron argued that Berger’s article had aligned the journal with ‘the stupid end of the Tory press’.41 The director of the Whitechapel Gallery, Bryan Robertson, argued that although Moore’s exhibition was ‘not the best one of his career to date, it contains some superb sculpture and marks a further stage in his development’; and visitors to his gallery preferred Moore’s work to the ‘gloomy and reactionary’ social realism Berger promoted.42 Even the President of the Royal Academy Sir Alfred Munnings weighed in, exploiting an opportunity to continue the theme of a widely reported 1949 speech he had made condemning Moore, Matisse, Picasso and the avant-garde in general.43

‘Isolation and Freedom’ 1954

In the August 1954 article ‘Isolation and Freedom’ Berger reviewed ‘The Sculptor in Modern Society’, Moore’s written contribution to the published proceedings of a 1952 UNESCO conference on The Artist and Modern Society. Although the distinction drawn in the ‘Piltdown Sculpture’ article between the ‘object’ made by a craftsman and the ‘image’ made by an artist could be read as an accusation of intellectual weakness (‘honest-minded’ is not far from ‘simple-minded’), the article ‘Isolation and Freedom’ made it clear that Berger respected the sculptor’s intellect, and even aspects of his politics.

‘We live in a transitional age’, Moore had argued in his text, ‘between one economic structure which is in dissolution and another economic order of society which has not yet taken definite shape.’44 Describing Moore as ‘very fair-minded and intelligent’, Berger repeated the Yorkshireman’s central question: ‘What, as Henry Moore asks, is the duty of an artist in an interim society such as ours?’45 Increasingly this would become the central question of Berger’s work: all of his projects – from A Painter of Our Time (1958) and Permanent Red (1960) to The Success and Failure of Picasso (1965) and beyond – would be direct or indirect attempts to provide answers to this problem.

‘Abandon Hope’ 1955

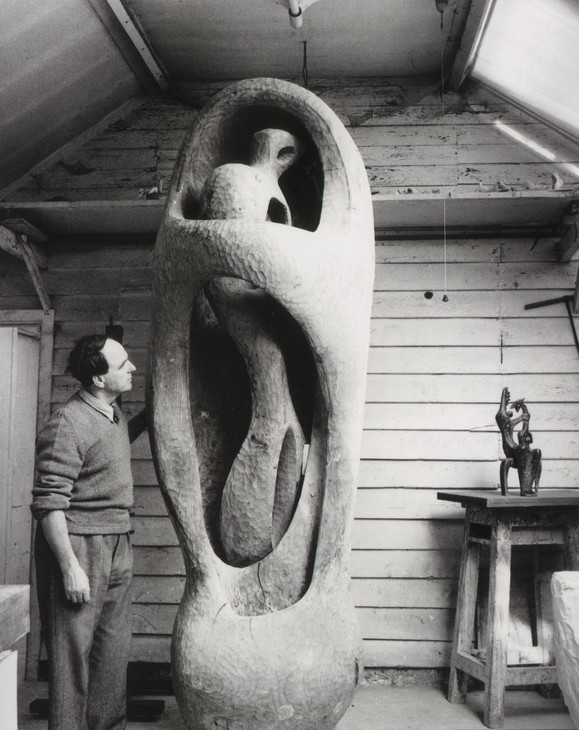

Henry Moore in the Top Studio at Perry Green with the unfinished Upright Internal/External Form 1953–4

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore in the Top Studio at Perry Green with the unfinished Upright Internal/External Form 1953–4

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Although he had recently pronounced positively on both Moore’s craftsmanship and thought, Berger continued to demur at the general ‘greatness currently heaped’ upon his erstwhile colleague.46 ‘Abandon Hope’, a review of another Leicester Galleries exhibition, qualified the views expressed in ‘Piltdown Sculpture’ but still indicated that the work on display did not offer, as far as Berger was concerned, any hope of a better future. The article focused on Moore’s Upright Internal/External Form 1953–4 (fig.4), ‘a variation on the theme of a Mother and Child’. This Berger considered ‘a work by Moore at his best’, ‘beautifully carved’ to suggest ‘the hand of a child tunnelling in the sand and making an underground cavern the shape of which he can feel but not see’.47 But, he continued, ‘Above the maternal casing should be written, “Abandon hope all ye who enter here.” Not because inside it is an obvious hell: but because in that mummy’s security (and I mean the pun) hope is unnecessary.’

For Berger, the work expressed an elemental state of consciousness at best: ‘It is a work based on an imaginative burrowing back into the darkness – and here the simile of the child burrowing into the sand has a Freudian significance – to rest there again without any of the awkwardnesses of being a conscious human being.’48 In contrast to the ‘excellent’ life drawings in the exhibition – rediscovered works from the 1920s which ‘vibrate with alternatives because their forms have been chosen from reality’49 – this piece was ‘the very opposite of a work that aspires.’50 The way Berger described the forms, as suggesting ‘no development’,51 echoed his earlier account of the Time-Life figure’s apparent hesitance to leave its ‘puddle’.

‘Round London’ 1958

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Bronze

object: 650 x 1540 x 850 mm

Tate T02278

Presented by the artist 1978

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore OM, CH

Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In ‘Round London’, a 1958 New Statesman survey piece that reported on a group show at the Marlborough Galleries, Berger welcomed Moore’s ‘impressive, well-wrought and tragically moving’ Falling Warrior 1956–7 (fig.5) as a sign of the end of ‘a difficult period’ for the artist.52 The work was, Berger thought, an attempt to produce an image devoid of sentimentality. This succeeded with the body, which searched for the ‘typical’ in the particular, but failed with the more generalised head, which was more like the ‘earlier, highly formalised heads of stones with holes right through them’.53 The review also offered an occasion for reflection on his and Moore’s trajectories: ‘In the past I have severely criticised exhibitions by Henry Moore and I still stand by these criticisms. Yet both critic and reader should always allow for the fact that the artist continues: that his perspective is his whole life’s work.’54

The perspectives of many left-leaning intellectuals in the West had been changed by the Soviet crushing of the Hungarian uprising in 1956 and Khrushchev’s ‘Secret Speech’ denouncing Stalin to the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. But in his debut novel, A Painter of Our Time (1958), Berger remained ambivalent, using the figure of a Hungarian émigré artist to work through the problem of what artists should do at such a time. As late as January 1957 Berger stated that his political allegiance to the global Communist movement remained ‘unbroken’ in the letters page of the New Statesman,55 but he confronted his own ‘red line’ when, in August 1957, the Soviet Union achieved nuclear parity with America, developing the R–7 missile capable of delivering a warhead to the US. In October Russia sent the Sputnik, the first artificial satellite into space, and one month later the Gaither Report described a fictional ‘missile gap’ between the US and USSR which John F. Kennedy, as a presidential candidate, later promised to close in his 1960 electoral campaign.56

Amid this growing tension between West and East Berger interpreted Falling Warrior as a protest against the prospect of nuclear war.57 Although he had previously argued that despite Moore’s capacities for both craftsmanship and intellectual insight the sculptor was producing work that was of no social or political value, he suggested here that the studies for this piece could have been used as an emblem for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Although no such drawings existed, the idea was one of the highest compliments Berger could have paid Moore. Falling Warrior was a work, he suggested, that went beyond the knowing and claiming of social rights to speak eloquently about humanity’s continued existence. It was an ‘image’ rather than merely an ‘object’.

‘Pre-Naturalism’ 1959

Henry Moore

Unesco Reclining Figure 1957–8

Travertine marble

Unesco, Paris

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Unesco Reclining Figure 1957–8

Unesco, Paris

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In ‘Pre-Naturalism’ Berger reviewed Moore’s UNESCO Reclining Figure 1957–8 (fig.6), the biggest commission of Moore’s career, according to Moore’s biographer Roger Berthoud.58 Moore had been asked for a bronze to sit in front of UNESCO’s Paris building but he felt that the metal would have been lost against the darkness of the building’s windows, and rejected the idea of creating a lighter-coloured background screen to compensate because it would have cut off the views from the building). Finally, he settled on carving a large, nine-ton, five-metre piece of Travertine marble.59 For Berger, the piece showed that ‘Moore’s work represents effectively and truthfully the modern artist’s struggle to achieve vitality, to discover a theme. It poses the problem, it begs for a solution, but it does not offer one.’60

Moore’s subject here is not a woman: it is the inert material he has in his hands. This work doesn’t challenge the reality of the human figure: it challenges the reality of the meaningless mass that it might so easily have been. It is an object striving to become an image: a prophecy of life not yet made manifest ... I believe that Henry Moore himself considers that most ‘interpretations’ of his work are so much nonsense. He is probably right. Not because many critics are fools, but because the problem of the meaning of his work haunts him and forces him round in circles so that finally his inability to solve it actually supplies him with his subject matter.61

It seems that Berger identified with Moore’s need ‘to wrestle even if unconsciously’ with his material, and resolved ‘so must we, too, but consciously and logically’ in the task of interpreting the work.62 (As Geoff Dyer has written of Berger’s work, ‘Essays by the usually cited contemporary masters of the form such as Gore Vidal or John Updike are marked by apparently effortless eloquence. In Berger’s case, by contrast, we come close to witnessing thought as an act of almost physical labour.’)63 Berger later included this article in the anthology of his essays about art and society called Permanent Red (1960), not in the section dealing with ‘masters’ (Gris, Zadkine, Léger, Picasso, Matisse and Kokoschka) nor in ‘artists defeated by the difficulties’ (Bratby, Dubuffet, Gabo, Hepworth, Klee, Pollock and Richier), but with ‘artists who struggle’ (Ceri Richards, David Bomberg and Friso Ten Holt, a close friend of Berger’s). It was Berger’s final word on Moore for the period, and included the admonition, ‘if Moore’s work is to last, its significance must become clearer’.64

1960s

In August 1968 Berger reviewed a book by John Russell on Moore, writing caustically:

‘Success and honour as offered by bourgeois society should no longer tempt anyone. The time when the bourgeoisie could offer true privileges has passed. What they offer now is not worth having.’ I wrote that five years ago concerning the bitter nature of Picasso’s success. Since then the observation has become even more obvious. This book is a token of the emptiness of such success.65

Berger was quoting here his own words in The Success and Failure of Picasso (1965), in which he had used Picasso as a model for his own self-imposed exile from Britain in the 1960s. Although living on the continent, Berger was clearly keeping abreast of British exhibition-making: that July, alongside the major exhibition of Moore’s sculpture he had curated for the Arts Council at the Tate Gallery, David Sylvester had written an innovatively thematic catalogue, highlighting the tactility and animal or sexual force of Moore’s sculpture.66 ‘Serious students of Moore’s work’, Berger continued in the article, ‘should read David Sylvester’s studies on the subject’.67

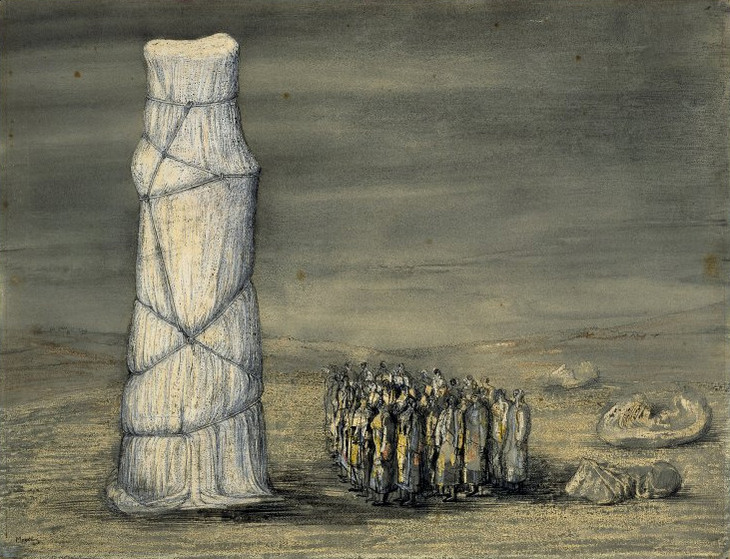

Henry Moore

Crowd Looking at a Tied-Up Object 1942

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Crowd Looking at a Tied-Up Object 1942

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Trustees of the British Museum

Although there were long periods in which Berger did not review Moore’s work, it remained something of a touchstone for him. In Art and Revolution: Ernst Neizvestny and the Role of the Artist in the U.S.S.R (1969), Berger noted that Neizvestny, a dissident Russian sculptor, admired Moore and had been influenced by him.68 He also included as an illustration Moore’s enigmatic drawing Crowd Looking at a Tied-Up Object 1942 (fig.7), but argued that the Russian’s work communicated a more powerful sense of a better future. ‘Moore’s imagination is oceanic: his figures are the creatures of forces that overwhelm them. His world, although his sculpture is entirely unliterary, is not unlike Thomas Hardy’s. Neizvestny’s imagination ... is anthropocentric and based on a heroic conception of the human will.’69 Here Berger returned to some of the arguments he had made in the 1950s about the fatalism of Moore’s work but the comparison with the nineteenth-century novelist Hardy was brilliantly fresh. Superficially, it was borne out by Moore’s 1977 claim to have read all of Hardy’s novels, and yet the comparison offered deeper insight into Moore’s political stance.70 The literary scholar Michael Millgate has observed ‘an intellectual progressivism and an instinctual conservatism’ in Hardy, who described his unpublished novel of the late 1860s, The Poor Man and the Lady, as ‘socialistic, not to say revolutionary’ but later, in 1892, declared himself ‘compelled to forego all participation in active politics, by reason of the neutrality of my own pursuits, which would be stultified to a great extent if I could not approach all classes of thinkers from an absolutely unprivileged point.’71

1986–8

By 1986, the year of Moore’s death, Berger’s body of writings on Moore had become a point of reference for a new generation. In October Anthony Barnett wrote an article on Moore’s achievement called ‘The Shape of Labour’ – dedicated to Berger on his sixtieth birthday – for Art Monthly and drew out some of the implications of the articles discussed above:

Around the world [Moore’s] work stands as a powerful statement. In its simplicity, its grandeur, its monumental strength, its great shoulders, its truth to materials its skill and craft, [his] work embodies the world’s first massed working class. Above all its suffering and passivity. For along with the strength of an ox went a similar inclination to obey. His figures do not rebel, they accept their sacrifice, they know but do not like their condition, they have the strength but not the will to rise. Moore’s figures come from a collective experience in which women toil the harder. They are the shape of industrial labour as a lifetime.72

The essay found a way to rescue Moore’s sculpture for the Marxist political perspective Barnett shared with Berger, understanding it in the context of ‘the long war that began as Moore’s father was taken from the fields to the mines, and which still continues as it hurtles us towards unknown destinations.’73

In 1988 Barnett returned to the subject, publishing a survey piece on the booming ‘industry’ of Moore literature. It argued that ‘Moore’s biography is significant because he beat a path right through the twentieth-century social history of England’.74 That year Barnett had also worked on England’s Henry Moore, a film part-financed by the Moore Institute that interpreted the work in the light of the biography (for example, linking Moore’s war service as a bayonet instructor and his later punctured figures).

By contrast, Peter Fuller published his memoir Marches Past in 1988, acknowledging that Berger, who had secured him Arts Council funding to write the book, had been ‘undoubtedly a “good father” for me, and thoughts about him and his work played a large part in my psychoanalysis’.75 Yet the book as a whole was also preoccupied with Edmund Gosse’s classic account of a difficult filial detachment, Father and Son (1907). As early as 1981 Berger had noted Fuller’s ‘“parricidal” need to disagree with me [which] is undermining the necessary intellectual honesty which a debate requires’.76 The disagreement centred largely on Fuller’s decision to jettison his earlier Marxism.

Also in 1988, Fuller’s article ‘The Value of Art’, among other things a means of launching a journal named after John Ruskin’s Modern Painters (1843–60),77 focused on Ways of Seeing (1972), Berger’s collaborative BBC TV series and book,78 and made the claims about Berger’s ‘hysterical’ attacks on Moore with which this essay began. Fuller’s attack, however, involved a wilfully selective misreading of Berger’s writings. Yet Berger’s response to Fuller also involved selective citation: where Fuller quoted ‘Piltdown Sculpture’ to denigrate Berger, the latter replied in ‘The Confession’ by dodging discussion of that text and quoting instead ‘Pre-Naturalism’.79 Reference to ‘Isolation and Freedom’, ‘Abandon Hope’ or ‘Round London’ might have dismissed Fuller’s claim more thoroughly but he may simply have used the passages he did because they were readily available in the anthology Permanent Red.

In any case, the episode seems to have stimulated Berger’s last great statement on Moore’s work, in which he declared it to be a source of not only critical satisfaction but also great solace.

‘A Sense of Touch’ 1989

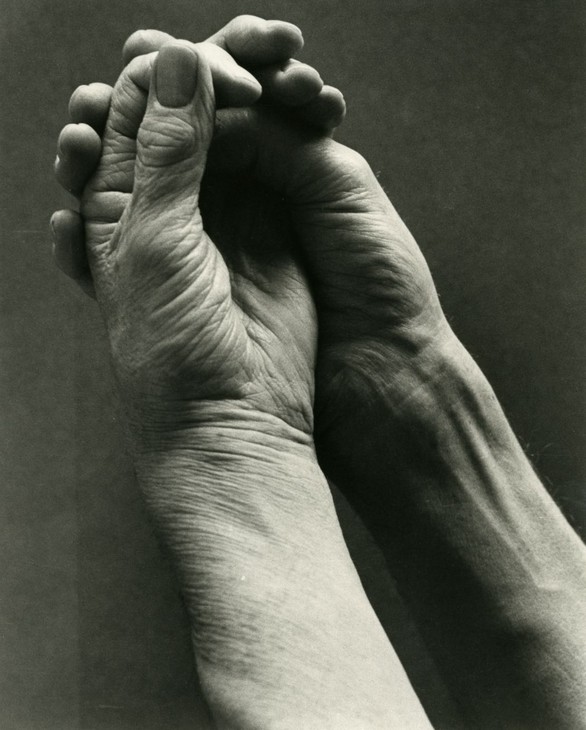

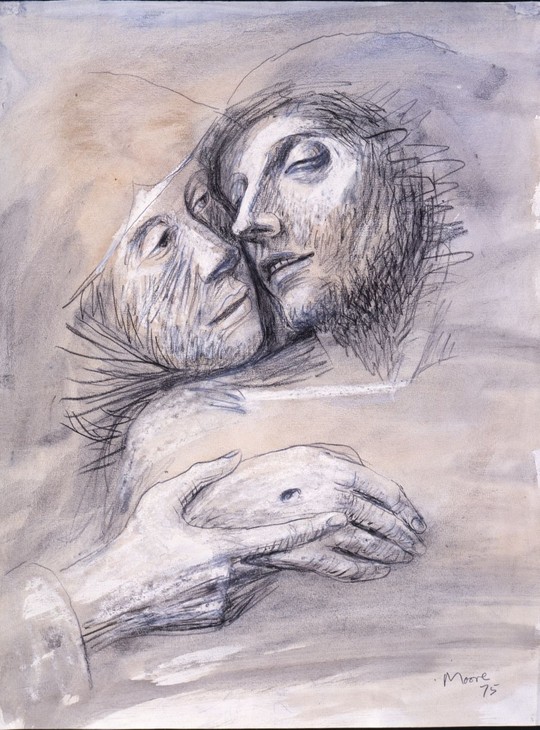

‘A Sense of Touch’80 was a complex, hybrid piece of writing. It combined a review of an exhibition of Moore’s work at the Fondation Pierre Gianadda in Martigny, Switzerland, something approaching an obituary of Moore and a summing up of Berger’s writings on Moore over the previous decades.

First published in the Guardian in September 1989, the essay began by discussing a black-and-white image of hands – ‘apparently of an old person. Perhaps a woman. Hands, one might guess, which have gardened, washed, cooked, ironed, consoled and dressed babies, fed children, washed many heads of hair’ (fig.8).81 The photograph was then compared to a drawing representing Giovanni Bellini’s Pietà 1460 (fig.9, where the heads of Mary and her son seem ‘hinged cheek to cheek, and the death on the one has printed the grief on the other’. Mary lifts the pierced hand of her son in her own, ‘her forefinger and thumb framing the hole driven through the flesh by the hammered nail’.82 Berger then broke the suspense and acknowledged that the drawing had been made by the hands shown in the photograph, those of Henry Moore, and used these images to re-evaluate Moore’s long production of tactile sculptural forms and the spaces within them.

Unknown photographer

Hands of Henry Moore

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Unknown photographer

Hands of Henry Moore

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Study after Giovanni Bellini's Pieta 1975

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Study after Giovanni Bellini's Pieta 1975

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Berger told his reader that he had begun like this, ‘because I want to try to liberate you from some of the stereotypes and critical clichés which surround the work of Henry Moore, three years after his death. These clichés are partly the result of his prestige as Britain’s most important twentieth century artist, and partly a product of the spite which characterises a great deal of post-modernist opinion-making’.83 He wanted to explore the role of context in interpretations of Moore’s work. In considering what ‘people across the world [are] likely, in the future, to find in his sculpture’84 Berger discarded the object/image binary that had featured in his previous essays and, side-stepping the question of what people would find in Moore’s sculptures, argued that they should find ‘a sense of touch’. Moore’s earliest successful work, Berger now reflected, had ‘little or nothing to do with objects’. ‘All of them possess a kind of body warmth’.85 The same could be said of Moore’s drawings, so clearly those of a sculptor in their apparent desire to grasp the objects depicted. But Berger tried to argue that his new emphasis on tactility was a continuation, rather than abandonment, of his earlier beliefs. Moore’s weakest sculpture had been made, he reiterated, ‘during the period when his work was most in demand and most critically unquestioned. Because of its underlying theme of pre-verbal experience, his work lent itself to a special kind of cultural appropriation ... A Henry Moore became an emblem for Time/Life magazine and, at the same time, for UNESCO!’86

Henry Moore

Mother and Child: Block Seat 1983–4

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Mother and Child: Block Seat 1983–4

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

For Berger Moore’s last years saw him join ‘the company of Titian or Matisse in the sense that his life’s work becomes cumulative’.87 Among his late works was one that Berger found exceptional: the over life-size Mother and Child: Block Seat 1983–4 (fig.10), which he interpreted as the culmination of a life spent searching ‘backwards – to find a way of expressing the child’s experience of the mother’s body.’88 If in earlier works, the perception of the child’s over-dependence on the mother had led Berger to say that they could be captioned ‘ABANDON ALL HOPE’, here hope arose from the relationship’s mutuality, the suggestion that the mother also depended on the child: ‘the nipple on the left breast, which does not stand up, but is a hole like a mouth of a sentient bottle; and the other is a protuberance on the child’s face which is like an eventual stopper for that hole, a stanch for that wound, a life for that nourishment’.89 ‘The last rite of the Egyptian burial ceremony’, Berger wrote to close the article, ‘was the opening of the mouth. The son of the deceased, or a priest, solemnly opened the mouth, and this act allowed the dead person who was in the other world to speak, to hear, to move, to see. In Henry Moore’s last great work the mouth has become the mother’s nipple.’90

Berger and Moore’s biographies are strangely intertwined on the issue of psychoanalysis. The child psychoanalyst Lyndsey Stonebridge has noted that the psychoanalyst ‘most often paired with Moore’ is D. W. Winnicott, a man perhaps most famous for his theory of the ‘transitional object’ such as the security blanket and the declaration that there is no such thing as a baby, only a mother-baby unit.91 By coincidence, Berger’s painting studio in the late 1940s was the maid’s room on the top floor of Winnicott’s house in Pilgrims Lane, Hampstead. Winnicott, he later remembered, would ‘often be on his hands and knees in the drawing room on the ground floor playing with and observing a baby, and I would be on the top floor ... Four days out of five it seemed hopeless – life was too big, and we would both console one another at the foot of the stairs ... Next morning the same infant and the same canvas would prompt us to try to advance further’.92 Yet Moore, though he acknowledged the relevance of psychoanalytic tropes to his work, famously refused to engage with them. Berger commented sympathetically in ‘A Sense of Touch’, that Moore ‘was fascinated not by emotions, but by touch: not by the deep unconscious but by surfaces and the tactile’.93 The writer had come to associate psychoanalysis with a doomed, and in Moore’s case, irrelevant, attempt to verbalise the pre-verbal.

Berger did not become reconciled to Moore’s work through jettisoning his politics. ‘A Sense of Touch’ was not a political essay in the sense that Barnett’s ‘The Shape of Labour’ was – perhaps because Barnett had covered that ground so forcefully. In Berger’s 1992 essay collection Keeping a Rendezvous, in which a lightly re-edited version of the essay appeared titled ‘Infancy’, he emphasised the significant changes in political context since he had first written about Moore. The Berlin Wall had fallen two months after ‘A Sense of Touch’ was first published, and the essays ‘The Third Week of August, 1991’, and ‘The Soul and the Operator’ (1990), responded to the collapse of the Soviet Union with this prediction: ‘The colossal economic difficulties of ongoing everyday survival are, in theory, going to be solved by the free market. With such a market comes the risk of new ravenous appetites for money, and with their voraciousness jungle law.’94

In 1994 Berger, who always described himself a Marxist, saw links to the past, to the dead, as essentially anti-capitalist:

Until the dehumanisation of society by capitalism, all the living awaited the experience of the dead. It was their ultimate future. By themselves the living were incomplete. Thus living and dead were inter-dependent. Always. Only a uniquely modern form of egotism has broken this inter-dependence. With disastrous results for the living, who now think of the dead as eliminated.95

During the Cold War, the moving physical tragedy of Moore’s Falling Warrior 1957–8 had struck Berger as an image capable of representing and uniting the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Now, he felt that the open, symbiotic warmth of Mother and Child: Block Seat gave sculptural form to the political and social necessity of staying in touch with the past.

Notes

‘Foreword’ in School of Art Prospectus, 1947–8 (Chelsea Polytechnic), C/SYLI/51, Chelsea College Calendars, King’s College London.

Lewis Jones, ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Wild Old Man’, Daily Telegraph, 23 July 2001, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/4724662/Portrait-of-the-artist-as-a-wild-old-man.html , accessed 26 November 2012.

Frances Spalding, Prunella Clough: Regions Unmapped, Farnham 2012, p.113. Berger was also teaching part-time in Richmond at the time.

Nicholas Wroe, ‘John Berger: A Life in Writing’, Guardian, 23 April 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2011/apr/23/john-berger-life-in-writing , accessed 28 March 2013. The Tribune’s literary editor was then the novelist George Orwell. See also James Hyman, The Battle for Realism: Figurative Art in Britain During the Cold War, 1945–1960, New Haven and London 2001, p.90, citing a 1993 interview with Michael Foot (p.230, note 14).

He is listed as such in the programme for the 1952 Chelsea Christmas ‘Stunt’, C/SYLI/53, Chelsea College Calendars, King’s College London.

Janine Burke, ‘Raising Hell and Telling Stories [interview with John Berger]’, Art Monthly, no.124, 1989, p.3.

John Berger, ‘Introduction: The Ideal Critic and the Fighting Critic’, Permanent Red: Essays in Seeing, 1960, London 1979, p.15. See also Frances Stonor Saunders, Who Paid the Piper?: CIA and the Cultural Cold War, London 1999, pp.369–80.

Unpublished notes for Unit One, 1934, Henry Moore Foundation Archive, cited in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.131.

As discussed later, Berger’s essay ‘Isolation and Freedom’ 1954 and his book Art and Revolution (1969) comment insightfully on the complexities of Moore’s politics.

Julian Stallabrass, ‘The Mother and Child Theme in the Work of Henry Moore’, in Henry Moore. Mutter und Kind/ Mother and Child, 1992, http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/people/stallabrass_julian/PDF/Moore.pdf , p.5, accessed 10 September 2015.

John Berger, ‘Fashionable Blinkers’, New Statesman and Nation, vol.56, no.1171, 15 August 1953, p.180.

John Berger, ‘Piltdown Sculpture’, New Statesman and Nation, vol.48, no.1199, 27 February 1954, p.250. Thirty-three pieces are listed in Catalogue of an Exhibition of New Bronzes by Henry Moore, Leicester Galleries, London 1954.

Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell, ‘Introduction’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, London 2003, p.2.

The sculptor Raymond Mason, referred to at the end of ‘Piltdown Sculpture’, remembered Moore describing this grouping at the time as ‘a fine little team of up-and-coming sculptors’. Raymond Mason, At Work in Paris: Raymond Mason on Art and Artists, London 2003, p.22.

Herbert Read, ‘New Aspects of British Sculpture’, in The British Pavilion: Exhibition of Works by Sutherland, Wadsworth et al, British Council, London 1952.

David Cohen, ‘Who’s Afraid of Henry Moore’, in Dorothy Kosinski, (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001, p.269.

‘British Council Fine Arts Committee Minutes, 1953–1978’, London. Many thanks to Amy Pettifer for making them available.

Henry Moore (1898–1986), Overview, British Council website http://visualarts.britishcouncil.org/collection/artists/moore-henry-1898 , accessed 5 June 2015.

Mason 2003, pp.23–4. Here Mason describes refusing to apologise, having his contrition reported to Moore anyway, and being invited to Moore’s home at Much Hadham. Many thanks to Jonathan Wood for drawing my attention to this.

George Richards, ‘Henry Moore [letter to the Editor]’, New Statesman and Nation, vol.47, no.1205, 3 April 1954, p.359.

Patrick Heron, ‘Henry Moore [letter to the Editor]’, New Statesman and Nation, vol.47, no.1200, 6 March 1954, p.288.

Bryan Robertson, ‘Henry Moore [letter to the Editor]’, ibid., p.289. This seems to have been a specific barb at Looking Forward, the exhibition Berger had curated at the Whitechapel in 1952. The gallery’s archives evidence the fractious interactions between Robertson and Berger as it was staged (‘Looking Forward Exhibition’, Whitechapel Gallery Archive, WAG/EXH/2/22).

Alfred Munnings, ‘Henry Moore [letter to the Editor]’, New Statesman and Nation, vol.47, no.1201, 13 March 1954, p.316. For his earlier speech see Stallabrass 1992, p.14.

Henry Moore, ‘The Sculptor in Modern Society (1952)’, in The Artist and Modern Society: Essays and Statements Collected by Unesco, Paris 1954, p.98, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0006/000668/066858eo.pdf , accessed 26 November 2013.

John Berger, ‘Isolation and Freedom’, New Statesman and Nation, vol.48, no.1223, 21 August 1954, pp.206, 207.

John Berger, ‘Death of a Hero [letter to the Editor]’, New Statesman and Nation, vol.53, no.1347, 12 January 1957, p.45.

John Berger, ‘Pre-Naturalism’, New Statesman and Nation, vol.57 no.1472, 30 May 1959, p.759 (commonly cited as ‘Henry Moore’).

Geoff Dyer, ‘Editor’s Introduction’, pp.ix-x in Geoff Dyer, Selected Essays of John Berger, London 2001.

John Berger, ‘Success Story [review of John Russell, Henry Moore]’, New Society, vol.12, no.306, 8 August, 1968, p.206.

John Berger, Art and Revolution: Ernst Neizvestny and the Role of the Artist in the U.S.S.R., New York 1969, pp.136–7. Berger argues that the ‘post-war work to whose spirit Neizvestny is closest is Zadkine’s Monument to Rotterdam ... the most successful figurative sculptural monument of the last twenty-five years in Western Europe’, and refers the reader back to the ‘fuller analysis’ in Permanent Red.

Conversation with Orde Levinson and David Mitchinson, 23 October 1977, typescript, Henry Moore Foundation Library, cited in Wilkinson, 2002, p.39.

The quotations are from: Michael Millgate, ‘Hardy, Thomas (1840–1928)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford 2004, http://0-www.oxforddnb.com.catalogue.ulrls.lon.ac.uk/view/article/33708 , accessed 30 November 2013; Thomas Hardy, The Life and Works of Thomas Hardy, ed. Michael Millgate, London 1984, p.63; and Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited, New York 2006, p.226.

Anthony Barnett, ‘The Shape of Labour’, Art Monthly, November 1986, available at openDemocracy, http://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/anthony-barnett/shape-of-labour-art-monthly-nove-1985 , accessed 17 October 2013.

Anthony Barnett, ‘Henry Moore and the Price of Fame’, Times Literary Supplement, 5 August 1988, available at openDemocracy, http://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/anthony-barnett/henry-moore-and-price-of-fame-1988 , accessed 17 October 2013.

John Berger, ‘Art Criticism’ [letter to the Editor], New Society, vol.57, no.977, 6 August 1981, p.239.

The first issue of which, we are informed in the margin of p.16, ‘will be published on 22 February, price £3.50’. Peter Fuller, ‘The Value of Art’, New Society, vol.83, no.1309, 29 January 1988, p.16.

Ibid. The child psychotherapist and specialist in autism Frances Tustin ended a chapter of The Protective Shell in Children and Adults (1990) – a book which bore an image of Moore’s Mother and Child: Bench Seat on its cover – by quoting ‘A Sense of Touch’ at length, arguing that ‘poetic and artistic expression ... can add to and supplement psychoanalytical theory’ (p.143). Another of Tustin’s publications offers a contrary reading of the piece, arguing that ‘The mother’s unswathed left breast has a black hole where the nipple should have been. The infant, although sitting on her lap, is cut off from touching here by the swathes which cover its body. Instead of a mouth it has a cork-like protrusion. This protrusion would block the flow of milk from the breast instead of being a means of sucking at it.’ (‘A Revised Understanding of the Etiology of Psychogenic Autism’, in Autistic States in Children, London and New York 1992, p.16.)

Lyndsey Stonebridge, ‘A Love of Beginnings: Henry Moore and Psychoanalysis’, in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, p.46.

Anne Michaels and John Berger, Railtracks with Photographs by Tereza Stehlíková, London 2013, p.31. In 2011, while I was cataloguing Berger’s papers at the British Library, his wife Beverly, who was largely responsible for their survival and order, contacted me on Berger’s behalf to ask for any records on the Berger-Winnicott relationship to help with something her husband was writing. It clearly preoccupied him, and I returned a scanned page of notes from around January 1975, which uses psychoanalysis to organise thoughts about the peasant subjectivities he was studying for Into Their Labours (1979–91), a trilogy of novels exploring the decline of the peasantry as a global class.

Tom Overton is a freelance researcher.

How to cite

Tom Overton, ‘'I tried to push him down the stairs': John Berger and Henry Moore in Parallel’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www