Introduction

For thousands of years the human figure has appeared in art. Early cave paintings show figures of hunters simply depicted using a few strokes. In ancient Greece human figures were the main subject on decorated vases. Through the ages the human figure has appeared in portraits, has been used to tell stories or express beliefs, or used to explore what it is to be human.

The human figure from life

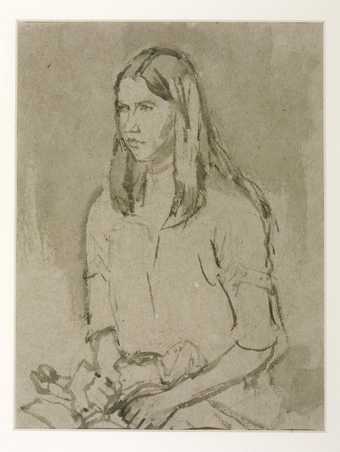

Myles Murphy

Figure with Yellow Foreground

(1974)

Tate

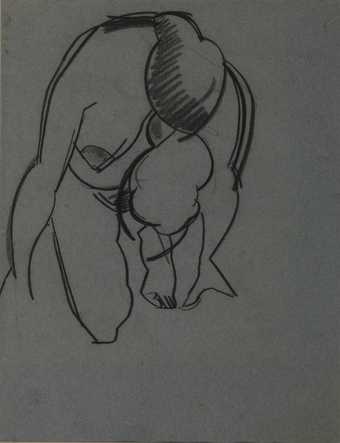

At art school drawing from the human figure is often one of the first skills taught. Life drawing helps young artists to look closely and understand proportions, as well as experiment with techniques.

Explore some of the ways artists have drawn and painted the human figure from life:

For most artists who draw, paint – or sculpt – ‘from life’ their fascination with the human figure is much more than simply creating an accurate representation of their model.

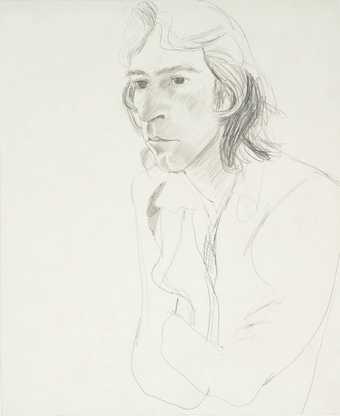

The painter Lucian Freud spent 60 years drawing and painting the human figure, mainly using friends and family as his models.

Lucian Freud

Girl in a Striped Nightshirt

(1983–5)

Tate

Although his drawings and paintings of people look like straightforward depictions, there is a psychological intensity to many of the portraits. The figures often seem awkward and their poses suggest vulnerability. As well as the phsyical nature of the human figure, Freud seems to also be exploring the emotional fragility that we as humans sometimes experience.

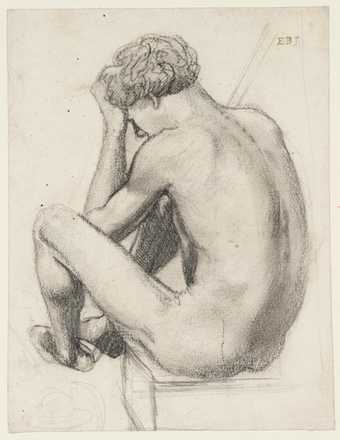

Gwen John

The Convalescent

(1918–19)

Tate

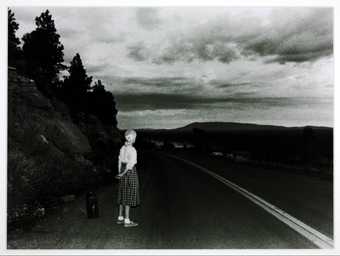

Emma Amos Eva the Babysitter 1973 Courtesy of Emma Amos, the Amos family, and RYAN LEE Gallery

Gwen John also seems to have been interested in capturing what people are thinking and feeling in her paintings of the human figure. The simple pictures of women in interiors suggest intimacy and quietness, but also often loneliness or sadness. Her drawings and paintings don't obviously tell a story. But by using harmonies of pastel colour, she creates a subtle sense of mood which gives the works their emotional impact.

As well as suggesting the psychology of their sitters, many artists want to suggest their character and celebrate who they are. Clothing and pose is important in doing this. Emma Amos’s painting Eva the Babysitter shows a woman dressed in jeans, t-shirt and trainers, sitting casually and smiling – as if sharing a joke with the artist. Her pose and causal look suggests confidence and that she is at ease with being painted.

Photographing the human figure

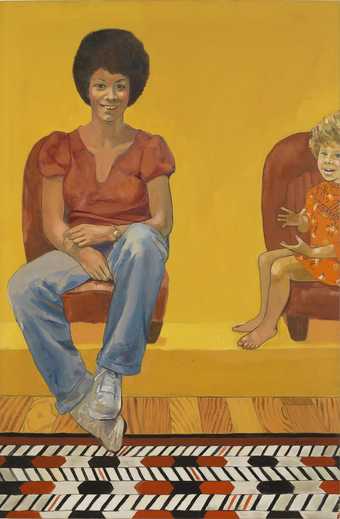

John Coplans

Self-Portrait (Hands Spread on Knees)

(1985)

Tate

Photographs by definition are taken from life. Photography is often used to capture or record the human figure.

John Coplans uses photography to scrutinise the relentless effects of ageing on his body. Although these are self-portraits, Coplans doesn't show his face. Instead he focuses on isolated body parts such as hands and feet (and knees!), showing them enlarged and close-up with every wrinkle and area of gnarled or sagging flesh brutally on show.

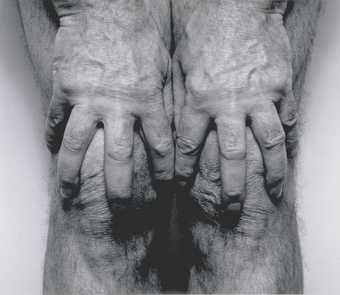

Samuel Fosso

Untitled

(1978)

Tate

Cameroonian photographer Samuel Fosso also uses photography to capture and explore who he is. He photographed himself in a series of adopted identities that often comment on the history of Africa. Dressing up in costumes ranging from European outfits and uniforms to African folk costumes, he reflects on how identity is often determined partly by things which we have little control over. He also suggests that regardless of outside factors, we can create our own identity.

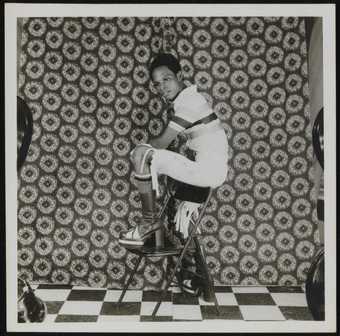

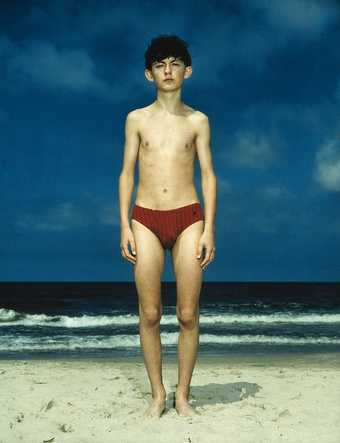

Rineke Dijkstra

Kolobrzeg, Poland, July 23 1992

(1992)

Tate

Rineke Dijkstra

De Panne, Belgium, August 7 1992

(1992)

Tate

For her series of photographs of young bathers, Rineke Dijkstra chose similar locations and set her camera at a relatively low viewpoint before inviting her subjects to pose. By using the same simple background for each photograph we focus on the figures. Each figure seems to be scrutinised by the camera (and by us), making them seem self-conscious and vulnerable. But at the same time the bathers scrutinise the camera. As a result, her images are filled with an uneasy intensity.

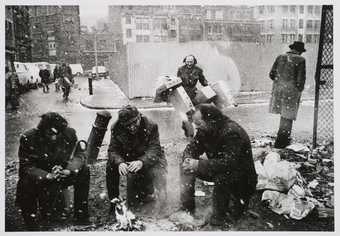

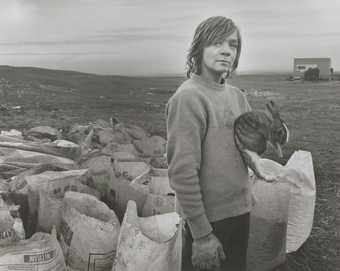

As well as documenting individuals, photography is often used to document the lives of people. Have a look at some of the ways photographers have captured the human figure in everyday situations.

Abstracting the Human

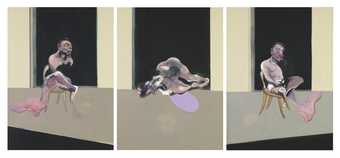

Francis Bacon

Triptych August 1972

(1972)

Tate

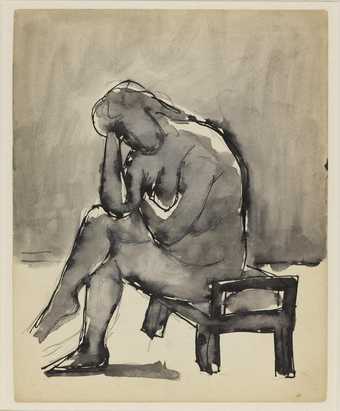

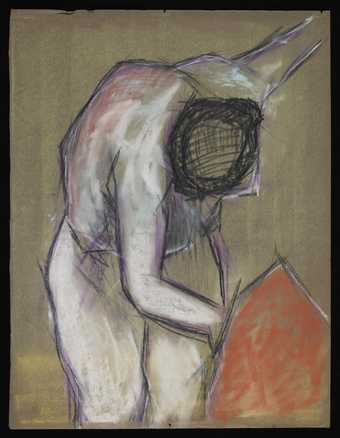

Artists often experiment with abstracting the human figure: either simplifying it or depicting it in a way that isn’t necessarily straightforward, often distorting elements of the body.

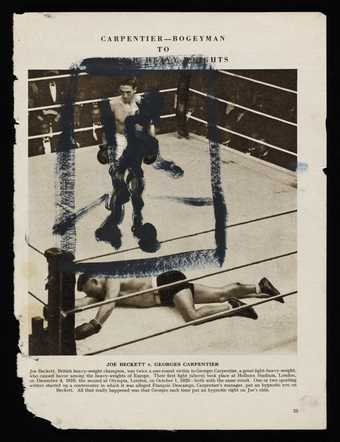

Have you ever experienced emotions – of anger, sadness or frustration – that are so intense you feel as if you are being tortured by them? How would you represent these feelings in art? Francis Bacon's twisted figures express a powerful sense of the psychological pain and anguish that people sometimes experience. He used photographs from books and magazines as the starting point for many of his paintings.

Extract from unidentified boxing magazine with photograph painted over by Francis Bacon 1950

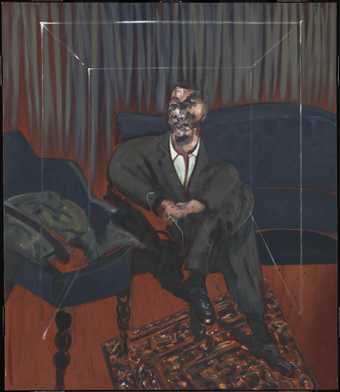

Francis Bacon

Seated Figure

(1961)

Tate

Many of the writhing, twisted poses were inspired by photographs of wrestlers. The distorted screaming faces have an unlikely photographic source – dental magazines showing diseases of the mouth! Bacon was also greatly inspired by artist Pablo Picasso's the abstracted figures.

In his paintings, Bacon often paints a square box around his figures. This makes them look as if they are trapped in a cage or other enclosed space, and adds to the sense of horror.

Artists are obsessed by life and by certain things that obsess them that they want to record. And they’ve tried to find systems and construct the cages in which these things can be caught.

Rebecca Warren OBE

Come, Helga

(2006)

Tate

Rebecca Warren's clay sculpture Come, Helga 2006 shows two female figures standing side-by-side. The kneaded, lumpy and messy figures challenge society's ideas about the ideal body. The work references a range of sources, from traditional figure sculptures to fashion photographers and cartoonists. The exaggerated proportions of the women's figures suggest clichés of the sexualised representation of women. However, the confrontational pose of the women is confident and complicates the way the figures are seen.

Sarah Lucas also explores female identity and how women are often sexualised. Like Rebecca Warren’s Helga, Lucas’s Pauline Bunny 1997 has a humorous cartoony look. Made from nylon tights stuffed with cotton wadding, the limp, floppy form undermines the fantasy of the glamorous ‘bunny girl’.

The human figure broken down

Parviz Tanavoli

The Poet and the Beloved of the King

(1964–6)

Tate

Often artists abstract the human figure by breaking it down into separate body bits or by adding other non-human elements. Eduardo Paolozzi adds machine parts to his figures, while Parviz Tanavoli adds architectural features. They create abstracted robot-like figures that perhaps comment on our lives and how we live them. In drawings such as Tree with Shoes 1998, artist Louise Bourgeois also mixes unlikely elements – such as tree branches – with the human figure. Her sculptures often include isolated body bits. She uses aspects of the human to explore of a range of themes including childhood memories, sexuality and mortality.

Romare Bearden

Pittsburgh Memory

(1964)

Lent by the Tate Americas Foundation 2017

African American artist Romare Bearden creates richly textured abstracted collages. His work focuses on unity and cooperation within the African American community. To create this powerful collage of two men, he has used elements taken from different found images from newspapers and magazines. In doing this the figures become universal. Bearden became a founding member of the Harlem-based art group known as The Spiral, which formed to discuss how African-American artists could help in the struggle for civil rights.

Douglas Gordon

A Divided Self I and A Divided Self II

(1996)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

The human figure broken down is also something artist Douglas Gordon explores in his video A Divided Self I and A Divided Self II 1996. Two arms – one hairy and the other shaven – are shown fighting each other on separate screens. On one screen the hairy arm defeats the shaven, while the reverse happens on the second screen. Gradually the viewer becomes aware that the arms belong to the same person suggesting a battle between two halves of the self.

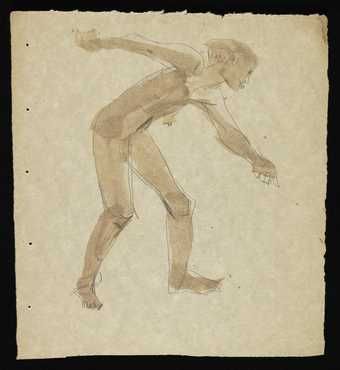

Moving figures abstracted

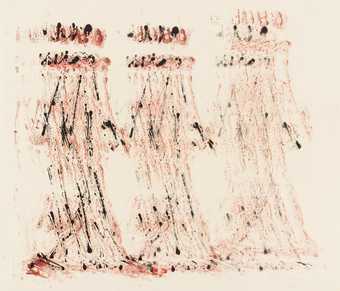

William Turnbull

Marching Figures

(1953)

Tate

Many artists have experimented with ways of depicting the human figure in motion. This often leads to abstracted representations of the human figure. William Turnbull explores very literally the act of walking in this print Marching Figures 1953. He said: 'I wanted to ...express the implication of movement (not describe it)’. The figures look a little like photographs of figures in motion created in the 1880s by Eadweard Muybridge.

In his painting The Mud Bath 1914, painter David Bomberg has reduced the human figure to a series of geometric shapes. The human figure is hardly recognisable, but the angled shapes suggest a very real sense of movement. Like many artists at the beginning of the twentieth century he was interested in finding ways of expressing the dynamism of the modern world.

Browse the slideshow below to explore more ways that artists have abstracted the human figure.

Telling Tales

Lubaina Himid CBE RA

The Carrot Piece

(1985)

Tate

© Lubaina Himid, courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London

As well as using the human figure as a way of exploring the human form or human psychology, the human figure is often used by artists to tell a story or to make a point. – exploring political or social ideas, or memories.

The figures in Lubaina Himid's Carrot Piece 1985 were cut out of plywood and painted. Carrot Piece shows a white man failing to tempt a black woman with a carrot. Her arms are already full with everything she needs. Himid says that the work was a comment on cultural institutions that ‘needed to be seen’ to be integrating black people into their programmes and the tricks they used to do this.

We as black women understood how we were being patronised ... to be cajoled and distracted by silly games and pointless offers. We understood, but we knew what sustained us… and what we really needed to make a positive cultural contribution: self-belief, inherited wisdom, education and love.

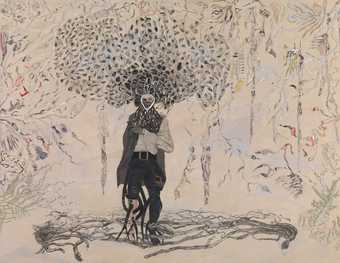

Ellen Gallagher

Bird in Hand

(2006)

Tate

Ellen Gallagher's multi-media painting, Bird in Hand 2006 is a dominated by the standing figure of a black sailor or pirate with a peg-leg and an abundance of swirling hair. He seems to be underwater as he is surrounded by trails of colourful shapes that resemble seaweed and marine-like vegetation. Gallagher often explores narratives surrounding the slave trade in her work. The undersea landscape is related to her imaginative exploration of the Middle Passage, the most treacherous part of the slave trading route between Africa and North America.

I think of this painting as an origin myth of sorts, with a kind of evil doctor, perhaps related to Doctor Moreau or Frankenstein, at its centre

Ellen Gallagher

In this video writer Bonnie Greer discusses the layering of narratives and ideas in Ellen Gallagher's work:

Explore more artworks in Tate's collection where the human figure is used to create narratives that tell stories or make a point:

Traces of the human figure

Pawel Althamer

Self-Portrait as a Businessman

(2002, with additions 2004)

Tate

Have you ever walked into a room and been aware of someone’s presence without anyone actually being there? We are not talking ghosts here! But what about an empty cup, some clothes strewn on the sofa, a TV or computer switched on? Art about the human figure doesn’t always actually include the human the figure. Sometimes human presence is suggested.

Body casts

Sir Antony Gormley OBE RA

Untitled (for Francis)

(1985)

Tate

Giuseppe Penone

Breath 5

(1978)

Tate

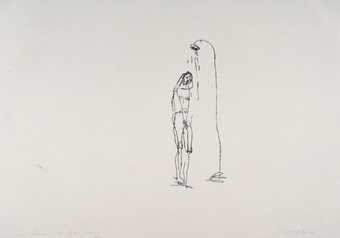

Anthony Gormley makes his sculptures of the human figure by making casts of his own body. He covers his body with plaster and then reinforces the plaster with fibre glass and lead. What we see looks like a simplified human figure, but in fact is an empty shell – the space where the human figure used to be. For Bed 1980-81 the shape of two human figures lying down are delineated in hollows eaten out of layers of sliced bread. The sculpture suggests carved medieval tombs. Gormley is from a Roman Catholic background, and is perhaps referencing the ritual of consuming the body of Christ through the taking of bread during communion. In this video Gormley talks about how he made the sculpture.

Artist Giuseppe Penone also uses an impression of his own body to create his sculpture Breath 5 1978. The clay is modelled on the imagined shape of a breath of air, exhaled from the artist’s mouth. At the top is the form of the interior of Penone’s mouth, squeezed into the clay. Along the side of the clay is an impression of the artist’s leg, wearing jeans, as he leans forward. Penone has made many artworks about the impression of man on nature. For Breath Penone has spoken of the influence of mythological explanations of the creation of man.

Body Extensions

What are these strange looking objects, and what have they got to do with the human figure?

These are sculptures – or body pieces – by artist Rebecca Horn. The body pieces, which include gloves and masks, are designed to extend the human body and what it can do. Although these artworks were made to be worn in performances, she also sees them as sculptures. Detached from the human figure and mounted on the gallery wall they look disturbing, suggesting a terrifying absence (or presence!).

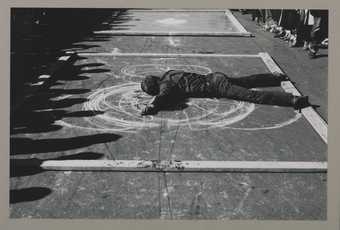

Artist as Art: The Human Figure as Medium

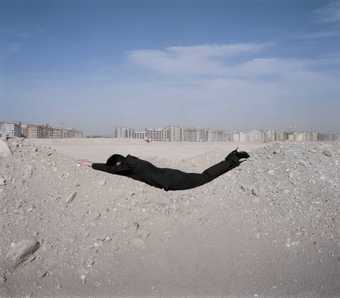

Carey Young

Body Techniques (after Parallel Stress, Dennis Oppenheim,1970)

(2007)

Tate

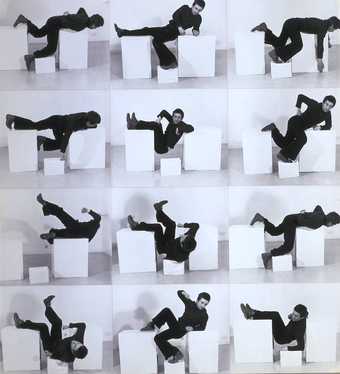

Bruce McLean

Pose Work for Plinths 3

(1971)

Tate

Stuart Brisley

Beneath Dignity

(1977)

Tate

So far this resource has explored some of the different ways artists have used the human figure as a subject in their art. But some artists use their own – or other people's – bodies directly as the medium or material for their art. For performance artists the artwork is created through actions performed by the artist or other participants. These may be live or recorded, spontaneous or scripted. Other artists use themselves as human sculptures.

Erwin Wurm makes art from anything that is to hand. His One Minute Sculptures were created on the spot using whatever objects, participants, and backgrounds were available. He then photographed or filmed these creations to document them. The improvised nature of the images, which show ordinary people and everyday objects, reflect the fun, playfulness and spontaneity that must have gone into the making of work. But in spite of their playfulness and humour there is also perhaps a darker suggestion of bullying, assault or ritual violence.

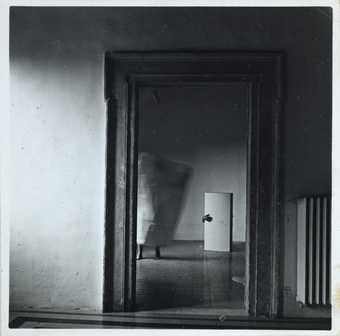

Francesca Woodman

Untitled, from Angel Series, Rome, Italy

(1977)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

© Woodman Family Foundation / Artist’s Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

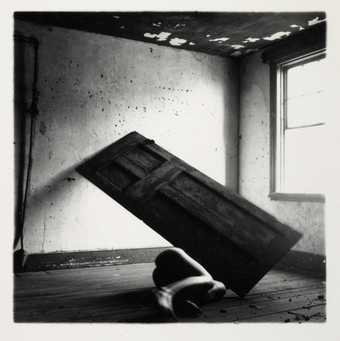

Francesca Woodman

Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island

(1976)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

© Woodman Family Foundation / Artist’s Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

Francesca Woodman often photographed herself half-obscured by various props – sometimes standing behind them and sometimes balancing them on top of her. Although she almost always present she is never quite visible or ‘fixed’.

When asked why she always appears in her own photographs, she responded:

It’s a matter of convenience, I’m always available.