This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 1234 x 1000 mm (figs.1–4). The canvas is a single piece of very fine, plain woven, linen with about 20 vertical and 17 horizontal threads per square centimetre (fig.5). There are few imperfections in the fabric, which appears to be of high quality. The tacking edges are not present, but cusping is evident along all four edges, indicating that we have the original or near-original dimensions.1

Fig.5

X-radiograph of Elizabeth, Countess of Kildare c.1679

The ground is opaque bright pink colour (fig.6). It contains the following pigments: lead white, red ochre, gypsum, umber, chalk.2 There is no priming.

Fig.6

Cross-section through a mid-tone of the brick red curtain, photographed at x160 magnification. From the bottom: pink ground; wet-in-wet brick tones of curtain; varnish

No underdrawing is detectable (figs.7–8). A few dark delineations around the eyes, visible only in infra-red reflectography, probably relate to an earlier painting stage.

Fig.7

Infrared reflectograph of Elizabeth, Countess of Kildare c.1679

Fig.8

Infrared reflectograph detail

A cross-section from the mushroom coloured skirt indicates that the figure was first brushed in sketchily with very thin brown paint (fig.9).

Fig.9

Cross-section through the sitter’s skirt, photographed at x160 magnification. From the bottom: Pink ground; very thin, dark brown wash; two shades of mushroom coloured paint of the skirt, worked wet-in-wet; dark brown shadow, applied when the underlayer was touch dry

The composition appears to have been planned carefully. Infra-red reflectography shows reserves for the head and hands in the drapery and background, and adjustments to the final painting are confined to boundaries or to folds in the drapery. Most of the picture was built up with dense, opaque tones applied wet-in-wet with feathery brushwork; the feathery strokes are very clear in infrared reflectography and x-radiography. Highlights were applied last (fig.10).

Fig.10

Detail of the nose at x8 magnification, showing highlit area applied last

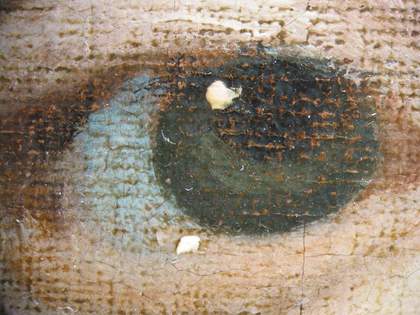

All the paint is well bound in oil. The lilac dress was built up from tones containing mixtures of lead white, vermilion, black, red ochre and lead tin yellow. Once dry, its shadows were glazed with a translucent brown containing red, lead white, black and fine opaque yellow. Some colours are based on very complex mixtures of pigments; the greens of the foliage, for example, were mixed from the following pigments: green earth, blue verditer, chalk, smalt, azurite, black, lead tin yellow, lead white, brown pink lake, traces of yellow and red ochres. Blue pigment was added to lead white for the whites of the eyes (figs.11–12).

Fig.11

Detail of the sitter’s right eye at x8 magnification

Fig.12

Detail of the sitter’s left eye at x8 magnification

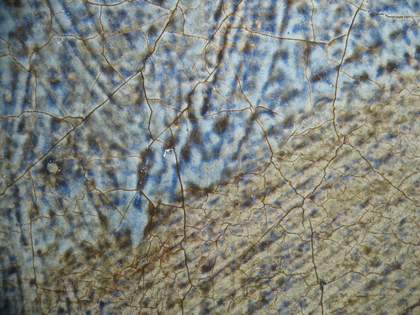

The blue mantle would originally have been a brighter blue. The basic blue pigments of its underpaint – smalt and indigo – have become paler and greyer with time, and its original final glaze of ultramarine mixed with chalk has largely disappeared (figs.13–14). Otherwise there appears to have been little significant change in the colours. Apart from some thinning of the dark areas the painting is in good condition. It has been lined at least once, and was cleaned and restored at Tate in 1958.

Fig.13

Detail of the blue drapery at x8 magnification, showing two shades of opaque, pale blue bodycolour and the remains of a blue glaze on top

Fig.14

Cross-section through blue drapery, photographed at x160 magnification. From the bottom: mushroom coloured paint of dress; pale blue opaque bodycolour; blue glaze.

(The ground is missing from this sample. Examination of the sample in ultraviolet light showed no fluorescence in the glaze, indicating a non-resinous binding medium.)

May 2005