This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 2222 x 1365 mm (figs.1–3). The single piece of plain woven, linen canvas has on average twenty-one vertical and eighteen horizontal threads per square centimetre (fig.4). The canvas is supported by a glue composition lining, which was probably applied in the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries. The adjustable wooden stretcher is contemporary with the lining. Although the turnover edges of the original canvas have not survived, cusping of its weave on all four edges of the painting indicates that little if any of the original composition is missing.1

Fig.4

X-radiograph of Portrait of a Lady, Called Elizabeth, Lady Tanfield 1615

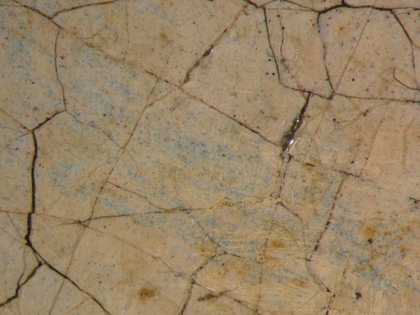

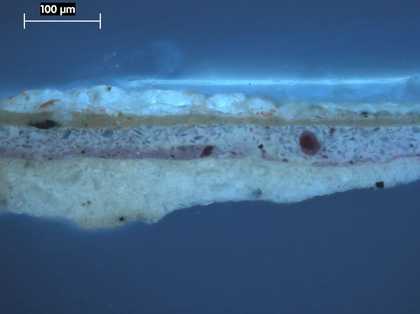

The thickly applied ground (up to 140 microns thick) is rich in marine chalk, with admixtures of lead white, fine black, red earth and cologne earth, altogether forming an off-white layer.2 Although probably bound in oil, this layer is friable and water-sensitive; delamination from the canvas support has been a problem in the past, now remedied by treatment at Tate in 1964. The priming is pale grey, on average half the thickness of the underlying ground and again is rich in chalk but with a higher proportion of lead white and bone black (fig.5).

Fig.5

Cross-section through the hand of Portrait of a Lady, Called Elizabeth, Lady Tanfield 1615, photographed at x225 magnification. From the bottom: off-white ground; grey priming; flesh paint of hand; varnish

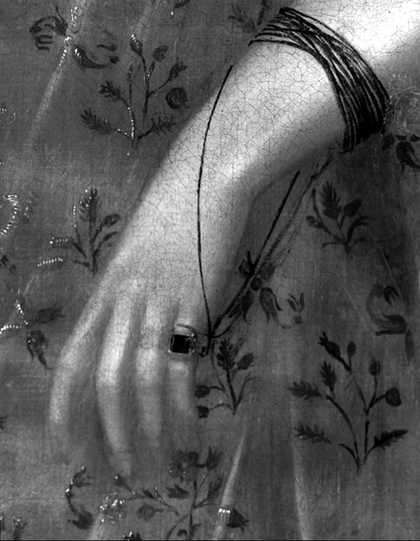

Boldly painted black lines are visible in infrared reflectography and with the unaided eye under parts of the red drapery (figs.6–14). These lines denote the approximate placing of folds and shadows. Softer lines were visible in infrared reflectography around the hands and the fold in the veil; on close examination, these lines seem to represent grey underpaint. There are slight indications of underdrawing in the face (fig.2), but it is possible that further fine drawing is masked by the high carbon black content of the paint (fig.5). Despite the scarcity of underdrawing, the artist planned the main areas of the composition carefully, leaving reserves for the figure, the areas of differently coloured drapery and some of the leaves and fruit of the tree. As work progressed, however, several alterations were made, for example: the red cloak originally extended over the sitter’s left shoulder across the background; the green cuff of the sitter’s left arm extends over the red drapery and the X-radiograph shows an alteration to the cuff (fig.4). Likewise, the position of the index and third finger of the sitter’s left was changed slightly. The infrared reflectogram shows that a black string around the little finger of the sitter’s left hand was painted out (fig.11).

At the stage of underpainting, both the green dress and the red cloak were blocked in with semi-tranparent mid-tones of the respective colours, after which the highlights of the folds were put in on top and some areas of shadow reinforced. Resinous grey paint occurs underneath the peaches and the leaves of the tree at the left (but not the trunk). This paint, which does not occur anywhere else in the painting, was laid in as a careful plan of the foliage and fruit.

Fig.16

Detail at x12 magnification of blue paint (probably the pigment azurite) worked wet-in-wet into flesh coloured paint in the sitter’s chest

The artist used two basic techniques for the painting: wet-in-wet work in the flesh tones, sky, building and landscape; and a more systematic, layered technique in the drapery. Blue paint was worked into wet flesh tone in the sitter’s chest to create blue veins (fig.16). Cross-sections through the blue lining of the red drapery show that each consecutive application of paint was touch dry before the next was applied (figs.17–18).

Fig.17

Cross-section through the blue lining of the red drapery, photographed at x250 magnification. From the bottom: trace of the ground at the left; grey priming; red paint; purplish blue paint; opaque yellow paint of sprigged decoration; opaque orange paint of sprigged decoration; varnish

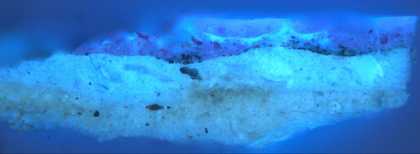

Fig.18

Cross-section through the blue lining of the red drapery, photographed at x250 magnification in ultraviolet light. From the bottom: trace of the ground at the left; grey priming; red paint; purplish blue paint; opaque yellow paint of sprigged decoration; opaque orange paint of sprigged decoration; varnish

In these samples, opaque red underpaint was glazed with blue (smalt) to produce a purplish shadow; in the same area subtly different shades of blue were produced by glazing over opaque blue paint with translucent red lake (fig.19). The white veil was painted on top of the sky, not as a pentimento but probably in order to give the illusion of the fabric’s transparency. The yellow lace trim in this area was superimposed on the already existent white lace decoration (fig.20), in order to match the yellow lace of the sitter’s cuffs and neckline, which seen to have been planned from the outset.

Fig.19

Detail at x8 magnification of another part of the blue lining of the red drapery. Here, opaque blue paint has been glazed with translucent red lake. The yellow decoration was applied when the red glaze was dry.

Fig.20

Detail at x8 magnification of the yellow lace trim of the veil, showing yellow paint applied on top of white

Pigments identified include: lead white, azurite, smalt, orpiment, yellow ochre, yellow lake, vermilion, red ochre, sienna, cologne earth, black with glass, chalk and pipeclay used as extenders. Smalt was used for the blue sky and the purplish blue drapery but the more highly coloured (and more expensive) blue, azurite, was reserved for the mixed greens, such as the dress and leaves. Overall the pigment particles seen at the surface, under magnification, appear large. Some fading has occurred in the red lakes.

December 2004