This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 1264 x 1814 mm (figs.1–3). The support is composed of three pieces of plain woven, linen canvas stitched together as shown in the diagram below.

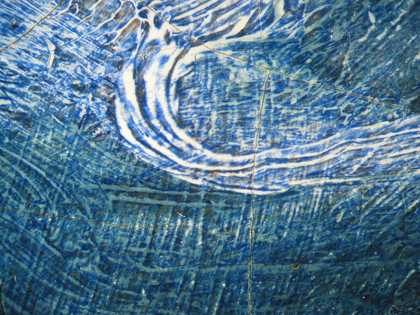

As visible in the X-radiograph (fig.4), the vertical seam joining the two principal pieces of canvas passes through the proper left arm and hand of the sitter in blue, who is on the left of the composition. The presence of cusping on all four edges of the right hand piece of canvas indicates that the portrait of the woman depicted there was conceived originally as a single portrait, although at 1219 x 1044 mm (48 x 41 inches), its dimensions were not quite the standard 50 x 40 inches (1270 x 1016 mm) of a sitter in three-quarter length.1 We have no clues as to why or when the artist decided to enlarge the composition. All three pieces of canvas have a similar thread count of about 16 vertical threads per cm square and 17 horizontal. The threads are of fairly uneven thickness, particularly in the larger right hand section, and this has been emphasized by later lining treatments.

Fig.4

X-radiograph of Two Ladies of the Lake Family c.1660

Close examination of the painting makes it evident that the portrait of the woman on the right was either very advanced or finished when the extension was added for the woman in blue. In the X-radiograph a reserve can be seen for the guitar to the left of the seam joining the two pieces of canvas. The fingerboard of the guitar passes across the seam but no reserve for it is evident to the right it; this area had already been fully painted. In the X-radiograph we can see also slightly curved, wedge-shapes behind the face of the woman in blue; they look like the beams from a low sun. If another composition exists beneath the woman in blue, there is no evidence of it elsewhere. The blue paint of the skirt appears consistent either side of the seam and the same is true of the sitter’s left hand, which also crosses the seam. One would expect some signs of reworking at the seam if two already existing paintings had been joined. The dark arch-shape visible in the X-radiograph to the lower left of the woman on the right appears to be part of the original 50 x 40 inch portrait. Perhaps, given the slight indication of water just to the left of the sitter’s sleeve, there was a small bridge in the original composition.

The painting has a glue composition lining, which probably dates from 1931 when the picture was with Leggatt Brothers before being sold to a private collection. The adjustable stretcher looks contemporary with the lining. It was made taller than at least one stretcher that preceded it, because it is clear from damage visible in the X-radiograph that the present top and bottom edges of the painting had earlier been folded back to create tacking margins. Much degradation of the canvas and loss of paint around the edges of the whole picture suggest that before its acquisition by Leggatt in 1931, the painting had suffered neglect.

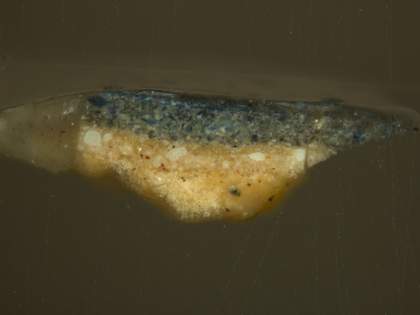

Fig.5

Cross-section through greyish blue sky near the top left corner, photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom: off-white ground; pinkish beige priming; greyish blue paint, containing smalt, lead white, indigo and black; thin scumble of brighter blue paint, possibly containing ultramarine

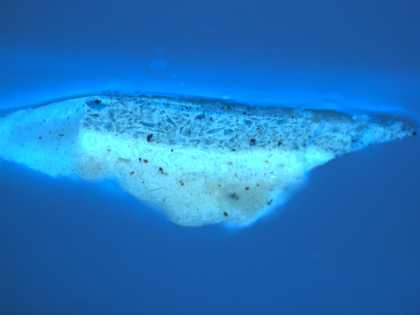

Fig.6

Cross-section through greyish blue sky near the top left corner, photographed at x200 magnification in ultraviolet light. From the bottom: off-white ground; pinkish beige priming; greyish blue paint, containing smalt, lead white and black; thin scumble of brighter blue paint, possibly containing ultramarine

The ground on the three pieces of canvas is off-white in colour and appears in cross-section to be a mixture of chalk with lead white and traces of black and ochres. Analysis with the polarising light microscope and EDX confirmed that it is rich in marine chalk and also contains gypsum. In all three pieces of canvas the ground is covered with smooth, opaque, pinkish beige priming, about 60 microns thick and composed of lead white, black, glassy particles and ochres bound together in oil (figs. 5–6).2

Fig.7

Cross-section through a shadowed fold in the blue dress, photographed at x125 magnification. From the bottom: off-white ground; pinkish beige priming; perhaps a trace of drawing (black particles left of centre); opaque, pale blue underpaint; blue glaze

Fig.8

Cross-section through a shadowed fold in the blue dress, photographed at x125 magnification in ultraviolet light. From the bottom: off-white ground; pinkish beige priming; perhaps a trace of drawing; opaque, pale blue underpaint; blue glaze; varnish

A cross-section from the blue skirt (figs. 7–8) shows what might be a faint trace of underdrawing between the beige priming and the opaque pale blue underpaint of the dress: a few dark particles set close together in a line but not obviously linked together with binding medium. Otherwise, as in most paintings by Lely, linear underdrawing, if present, is elusive in all normal methods of detection (figs. 9–13).

Close examination of the painting’s surface indicates that the initial lay-in of both figures was done in thin, reddish brown paint. This was common practice in Lely’s portraits.3 With this paint the artist would have established the overall shape and bulk of the figures and made an approximate placing of the features. It remains visible as the shadowed definition of many areas of the figures, sometimes strengthened by a glaze of similar colour (figs.14–15).

Fig.14

Detail of the hands and skirt of the woman on the right, showing reddish brown initial painted delineation left visible as the shadowed definition of the hands and folds

Fig.15

Close-up detail of the sitter’s left hand

The next stage was what the manuals of painting call the ‘first painting’ or ‘dead colouring’. The sky was underpainted in thick greyish blue, composed mainly of the blue pigment smalt mixed with white lead and black (figs.6–7). The blue dress was fully modelled with tones of white, powder blue and greyish blue, mixed from white lead with the blue pigments indigo and smalt, and black. For the red curtain the artist mixed shades of brown to establish the folds (fig.16).

Fig.16

Cross-section through the red curtain at the right edge, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: sliver of pinkish beige priming; opaque dark underpaint; opaque red paint

For the sitters the artist mixed on his palette slightly muted, naturalistic tones and worked them together on the painting to produce the fleshtones and the features of the faces. In certain areas these cool tones would be left visible to form recessive parts, for example in the face of the woman on the right: the eye sockets, the far side of her neck, the ringlet and the skin immediately around it (fig.17).

Fig.17

Detail of the older woman’s face, showing the muted tones of the first painting or dead colouring allowed to show as the recessive areas of face and neck: the eye sockets, the far side of her neck, the ringlet and the skin immediately around it

When all these areas were dry, the artist applied the final painting. We can see in the face of the woman on the right that he applied thick, bright paint to the prominent parts of the face, neck and shoulders, bringing his loaded brush almost to the ringlet but leaving the muted first painting to show around it (fig.17). Much of this thick brushwork was applied with strokes that emphasise the shape of the features. In the blue dress he applied a translucent blue glaze over all the underpainting (fig.18).

Fig.18

Detail of the blue dress at x8 magnification, showing two shades of underpaint – white and pale blue – glazed with dark blue, which contains ultramarine

Fig.19

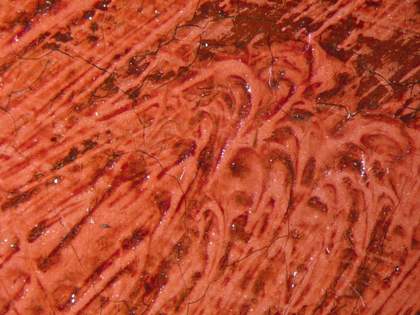

Detail at x8 magnification of the red curtain, showing opaque red paint glazed with translucent red and also dark red

This translucent blue colour contains the expensive pigment, ultramarine, as well as lead white, indigo, smalt, yellow lake and red lake. Bright opaque red and translucent red glazes were applied to the brown tones of the curtain (fig.19), and the sky was finished with thin applications of brighter blue tones; like the dress they contain ultramarine.

Fig.20

Detail at x8 magnification of the eye of the older sitter, showing black pigment mixed with white for the recessive curve of the eyeball

Fig.21

Detail at x8 magnification of the eye of the woman in blue, showing blue pigment mixed with white for the recessive curve of the eyeball

The bronze coloured dress was made from tones mixed from the blue pigment azurite, with white lead, yellow ochre, raw sienna, smalt, Cologne earth and black. Like all painters in this period, Lely used complex mixtures of pigments to achieve a range of subtle tones. Other technical features worthy of note are that the flesh tones contain much black pigment as well as white lead and opaque red. For the recessive curve of the whites of the eyes, black mixed with white lead was applied in a thick scumble in the face of the woman on the right, whereas a blue pigment resembling ultramarine was mixed with white lead for the equivalent in the woman in blue (figs.20–21). The brushwork throughout the composition is direct, lively and assured (figs.22–26).

The painting was cleaned and restored at Tate in 1999.

January 2005