Ocean is an archive. One body of water can contain so many layers of history. And after each tide, after each storm, the new layer of history unfolds. This call to emerge and submerge in the water comes driven with intuition. It’s time for water. It was calling me home.

I’m Emilija Škarnulytė from Lithuania, mostly working with moving image. Through my moving image works, I look from cosmic to geological, from ecological to political. Often I try to create these temple-like immersive spaces where we could bring back the respect to the exploited body of water. I feel it’s very important, and through my work I always try to return to different values of being together, to the ritual, to the myth.

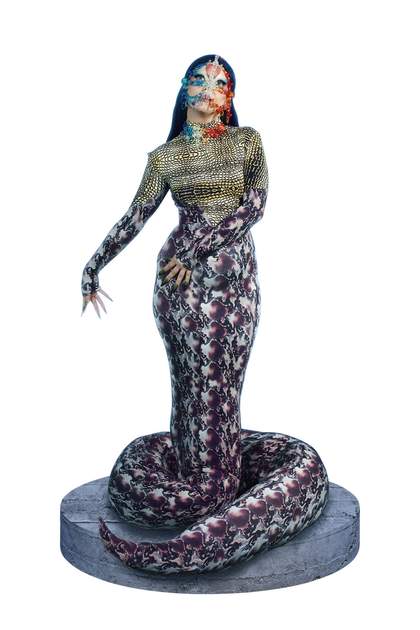

To measure the landscapes, I’m often using my own body as a scale or a shapeshifter creature. I always wanted to show these hidden, unknown worlds through a mythological character’s perspective. I started to train my own body, expanding lungs, breathing.

In one of my first videos where I’m using my own body, I’m trying to measure these invisible Cold War structures in the Arctic Ocean, in a decommissioned NATO submarine base, where I swim in four Celsius water and try to guide the viewer through a mythological character’s perspective. Seeing these ruins and human-left scars, the body becomes just a measuring tool of history, time, and geopolitical landscapes.

In Æqualia, two rivers in the sacred confluence form one of the biggest rivers in the world, the Amazon. One river with sediments meets Rio Negro another, very hot and warm, full of bio debris and matter. I was piercing it through and measuring it using my own body, swimming alongside pink river dolphins, botos. It was a very scary and unknown experience, not only due to the rivers going in different directions and pulling, but also the notion of other beings being around me. But the call was so strong to immerse.

It’s being said that we have this mammalian effect so when you put your face in the water, other kinds of senses remember being fish. So it’s really about being present in the moment during the dive.

I feel the need to go back to this geological time perspective and deep time perspective, but it’s really hard. You know how a single-celled organism sees the world, how mineral or uranium sees the world. Sometimes I’m using 3D simulations, sometimes slider scans, sometimes four-kilometre-depth submarine cameras that help to pierce through portals and touch this liminal space between the visible and hidden quantum world.

Telstar is a new two-channel 16-millimetre piece created here during the residency at St. Ives. I was visiting many different stone circles, megalithic ritual sites, as well as Goonhilly station. We see the drawings that I made from ground minerals, sea water, volcanic sediments, and salt. It’s a reflection on humanity’s eternal need to communicate to the cosmos or something larger than us leaving a message.

I see moving image and video installations more as sculptures in space. Sound has the same importance as the image. We could close our eyes in the space, but we still could experience those sites and locations.

In the main installation, we see four screens standing as megaliths, as dolmens in the field. So moving image becomes a sculpture embracing us, and the light and pixels become like water flow, showering us. The most important thing for me is how the viewer flows in the space, how their body receives that emitting light and sound, and how the other senses of the viewer can be activated.

All my pieces are time-based and durational, with a rhythm. So being here at St. Ives, having this rhythm of tides because these landscapes were formed by water, by ice too. Water is also the origin. We are made from water, and eventually we might go back to water.

Artist Emilija Škarnulytė often places her own body at the centre of her work, moving through environments and adopting hybrid, mythical forms to explore underwater worlds and spaces rarely seen. Shifting between human and non-human perspectives, she creates a way of looking that blurs the boundary between documentary and the imaginary.

In this film, we follow Škarnulytė as she swims through Arctic submarine bases and sacred river confluences in the Amazon, reflecting on the physical experience of being in the water. The film also looks at Telstar, a work made in Cornwall, where stone circles, megalithic sites and satellite communication come together. Moving between underwater landscapes, ancient mythologies and the traces of human history, Škarnulytė invites us to reconsider how bodies, water and time are connected.